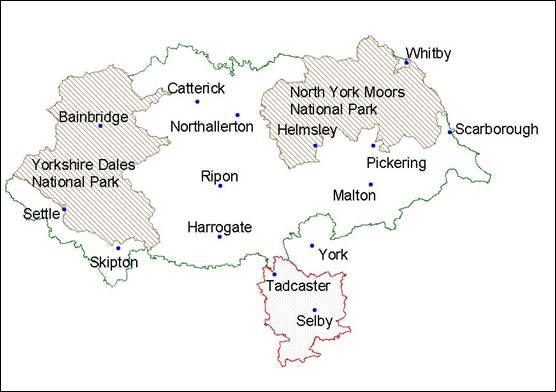

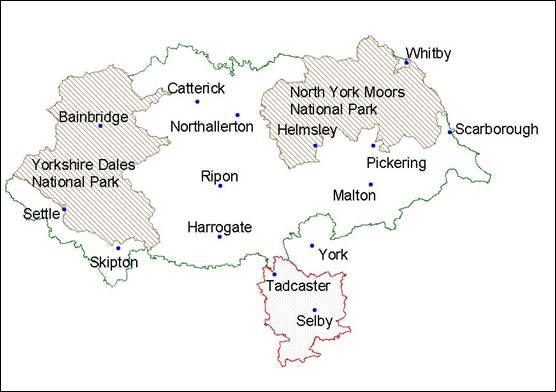

Figure 1: North Yorkshire County Council SMR/HER area from April 1997, with Selby district highlighted (red). Crown Copyright North Yorkshire County Council Licence No. 100017946 (2005)

The article is a summary of my dissertation project (PDF 2.1 MB) undertaken as part of an MSc in Archaeological Information Systems taken at York University, between 2003 and 2005.

In the UK, the workload of development control (DC) archaeologists is such that speedy decisions have to be taken about the archaeological potential of a development area, increasingly based on data in the Geographical Information System (GIS) (Gail Falkingham, pers. comm.). However, it is possible that certain data are likely to be omitted from this assessment owing to the way information has been mapped. Discussions with Historic Environment Record (HER) colleagues has suggested that they are aware that even imprecisely located artefacts can add to the archaeological potential of an area (Barry Taylor; Vic Bryant; Louisa Matthews: pers. comms.).

In light of this, the aim of the project was to develop a methodology which would allow stray finds data, which are often only imprecisely recorded within HERs, to be incorporated into GIS mapping in such a way that they can usefully influence DC decisions.

In the following discussions it is important to understand the distinction between the recording of artefacts and the recording of findspots. An artefact could be recorded as part of an excavation record and linked to the generic site record for the excavation. However, findspots refer to artefacts which were found 'off site', either during structured archaeological field work or during other activities. It is possible to record similar data about the artefacts recovered in both cases, but in the latter case, it is not possible to posit a 'site' from which the artefacts came - either because not enough data are known, or because, in fact, no such 'site' exists. My concern in this article is with these 'off site' or stray finds.

For various reasons, some artefacts are often only recorded to an area location, such as a grid square, parish, or quarter sheet location. This can be a result of the location coming from antiquarian sources (rendering it impossible to reinterrogate to determine a more precise location), or because of unwillingness to give more precise detail by more modern finders, such as some metal detectorists.

However, to understand the archaeology of an area fully, even 'fuzzy' data such as these need to be borne in mind otherwise evidence of activity may be missed, which may not be visible from other complementary sources, such as earthwork or aerial photographic evidence. An example of this is given by Phillips (1980, 19-20), where he explains that the mapping of antiquities on Ordnance Survey (OS) maps has often led to the discovery of more extensive sites by later researchers.

The problem of mapping imprecisely located artefacts has been with archaeology for some time, and a satisfactory solution has never been found. In map and card-index based analogue systems a number of pragmatic solutions were worked out, initially as part of the OS card index system, which later became the basis of many SMR systems (Lock and Harris 1992, 187; RCHME 1993; Murray 1999, 236; Gilman 2004). These solutions can be classed as map based and non-map based. On maps, the pragmatic solution was marginalia notes, which informed an examiner that some artefacts of archaeological interest were found somewhere on a particular map. The non-map based approach involved putting a record of the artefacts in the relevant section of the parish-based filing system so that a similar note would be made by those researchers using parish-based research methods (OS 1978).

The main guidance on establishing SMRs (Baker et al. 1978) also influenced practice on artefact recording. The guidance suggested consideration of artefact recording, but also suggested that this would be less of a priority than the recording of sites, and that artefacts from sites could be relegated to the archive sections. This view can be seen to have been further entrenched by the Monument Inventory Data Standard (MIDAS) (RCHME 2003, 3rd reprint) which has become the model for the development of most HERs (Baker 1999; Fernie and Gilman 2000; EH and ALGAO 2002). MIDAS proposes the use of the Events-Monuments-Archives (EMA) model (see e.g. Bourn 1999; Catney 1999; Fernie and Gilman 2000; RCHME 2003 for fuller description of EMA model).

The key issue for this project is that the EMA model deals very superficially with artefacts. Artefacts are seen as being part of the Archive Section of the model (RCHME 2003, 49-50). MIDAS also states that its aim is to record monuments rather than individual artefacts (RCHME 2003, 49) though it also notes that findspots of individual artefacts may sometimes be useful to record (RCHME 2003, 18, 49).

In the digital age, the constraints of fitting data, to a certain extent, into a yes/no, off/on or 1/0 format have rekindled debate about the mapping and recording of finds, or, more precisely, re-cast them in a different medium. This problem has been hidden by the fact that often the computerised compilation of most Sites and Monuments records (SMR) was done with the focus on trying to achieve data entry as quickly as possible, given the mass of data accumulated over the years of the SMR.

However, now the dust of the SMR digitisation stampede has begun to settle somewhat, more thought is being given to what data are actually in the SMR. This has also been prompted by the switch in emphasis from SMR to HER, as detailed in, for example, Historic Environment Records: Benchmarks for Good Practice (EH and ALGAO 2002). Another influencing factor is the emergence within archaeology of the role of full-time data managers (e.g. Baker 1999 records at least 21 officers in this role), as opposed to officers whose duties were split between DC work and data management, and who were quite often under too much pressure from their DC-related activities to be able to worry about such issues. These various factors have helped engender a period of reflection regarding HERs generally, but also regarding artefact recording within HERs (Fernie and Gilman 2000, C11).

Further prompting has come from the establishment and expansion of the Portable Antiquities Scheme. This has created a new system of recording artefacts, and has rekindled the debate to some extent (Fernie and Gilman 2000, C11; HER Forum Email List Archives April 2001; Gilman 2004).

The final prompt has been the rapid increase in the use of GIS by HERs. In 1997 there were approximately 20 using some sort of GIS (Foard 1997) and this had risen to 22 (29% of HERs) by 1999 (Baker 1999, 18). The most recent survey showed 88% of HERs using GIS (Newman 2002, 16). The way GIS has mapped data has highlighted the problems mentioned above, notwithstanding the early recognition of some of the issues relating to mapping precision (e.g. Lock and Harris 1992).

There have been various solutions to mapping imprecisely located artefacts within digital HERs. It is common for most findspots to be mapped as a point within HER GIS systems, though experiments are also beginning with mapping artefacts to polygons (Victoria Bryant, pers. comm.; Fernie and Gilman 2000, B30). In some HERs, artefacts are only recorded in the GIS if they can be mapped to a kilometre square. Artefacts located less accurately than this are either recorded only in the database and need to be retrieved by a separate query (Alice Cattermole, pers. comm.; Sarah Poppy, pers. comm.), or are simply put into a paper parish information file (Louisa Matthews, pers. comm.) which will need to be manually searched. Other solutions are also possible (see e.g. PastMAP, which has used colour coding points to reflect accuracy.)

The use of point mapping means that artefacts only recorded to a four-figure National Grid references (NGR), are commonly clustered in the bottom left-hand corner of a grid square. The problem of quarter sheet and parish-level artefacts is even more complex. Often an arbitrary point within the parish or quarter sheet may have been chosen to represent these artefacts. However, if an area just off-screen from these points is interrogated, the data they represent are essentially ignored in decision-making processes, giving distorted views of the archaeological potential of an area. For those items not mapped at all, they obviously cannot easily be taken into account in DC decisions.

In this project I have experimented with alternative methods for mapping artefacts in order to produce what I have termed an Artefact Density Index (ADI) for areas which will, hopefully, more usefully reflect the pattern of activities across the landscape.

With artefacts, as with all archaeological data, there is an almost infinite amount of information that could be recorded. However, in practice there is a common subset of data which is usually recorded within the HER-type datasets. The main data of possible relevance to this project were considered to be location, period, type of artefact and material. The standards discussed above mean that period and artefact type are usually recorded according to the Archaeological Periods List (RCHME 1998) and Archaeological Objects Thesaurus (AOT) (MDA 1997), respectively.

Some thought was given to various ways of categorising finds in the model, including artefact material, ranking artefacts and mapping artefact types to monument types. These were all abandoned owing to various problems and eventually it was decided to follow the suggestion in Haselgrove (1985) and link the categorisation of artefacts to functional categories. Given that the AOT already grouped artefacts by categories, it was decided to use those groupings.

In attempting to look at possible solutions to the above issues, I developed and then tested a methodology for this on a subset of the North Yorkshire County Council (NYCC) HER, and data from the PAS for the same area. The area finally chosen was in the Selby district (see Figure 1) and had the minimum bounding rectangle National Grid co-ordinates of Easting 450000 Northing 430000 to Easting 460000 Northing 440000.

Figure 1: North Yorkshire County Council SMR/HER area from April 1997, with Selby district highlighted (red). Crown Copyright North Yorkshire County Council Licence No. 100017946 (2005)

However, it must be borne in mind that the aim of this project is not to create a tool which can be used in isolation to make DC decisions. The aim is specifically to deal with scattered and imprecisely located artefacts and to try and integrate these into the DC process. As such, it is envisaged that the DC ADI will be an additional layer of information which will help inform DC decisions.

© Internet Archaeology

URL: http://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue21/1/1.html

Last updated: Wed April 25 2007