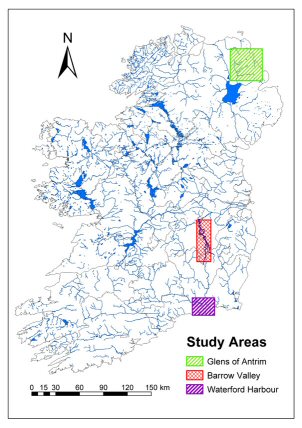

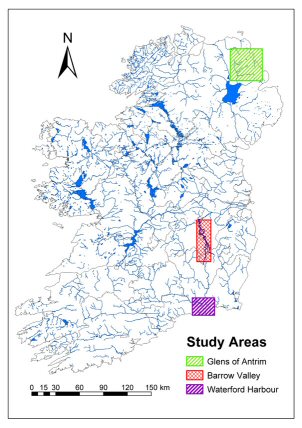

Figure 1: Location map of all three case study areas

Figure 1: Location map of all three case study areas

Some 80 km further north along the river Barrow (Figure 1), Ireland's second largest river, an intensive programme of fieldwalking over two seasons from 1990 to 1991 was conducted also by the BLAP. This has produced a small lithic assemblage of 803 artefacts 39 (4.9%) of which were identified as diagnostic mesolithic pieces. It appears that the largest part of these objects was manufactured on what could be described as local raw materials. Almost three quarters (71.8%; n=28) of them are made of chert (Figure 6) which can be found in outcrops of the Carboniferous limestone to the west of the study area as well as in glacial drift deposited throughout the valley (Feehan 1983, 26 - 27, 95).

Figure 6: Early prehistoric artefacts from the Barrow Valley made of local chert

Equally most of the flints, making up about 20% of the overall assemblage, appear to have been derived from local sources, primarily in the form of small riverine and glacial drift pebbles that can be found in limited quantities throughout the Barrow Valley. However, a small proportion of the flint objects is too large in size and too high in quality to have been obtained from these local drift pebbles (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Flint artefacts from the Barrow Valley; top: small flakes and blades made of local flint; bottom: a large later mesolithic flake of 'imported' flint

The only known Irish source yielding such good quality flint pebbles and nodules large enough to make these objects is the northeast of the country, along the north Leinster or East Ulster coast, located somewhere between 100 and 200km from the Barrow (Figure 8). Interestingly the large flint objects in question represent almost without exception diagnostic mesolithic forms and also show significantly more intensive retouch than any of the other objects within the Barrow valley assemblage. This could be interpreted to further supporting the notion that these objects were moved considerable distances but also that people kept them in circulation for prolonged periods of time. Another diagnostic later mesolithic objects made of rhyolite was found at the northern limit of the study area (Figure 9). This object appears to have originated from broadly the same region as the large flints, also located some 150km northeast (Rynne 1983/84; Kador 2007, 37 - 40).

Figure 8: Carnlough beach, County Antrim; potentially one of the main sources of large pebble flint found in the Bann Valley and elsewhere in Ireland.

Figure 9: Later mesolithic 'Bann Flake' found at Clogheen, Co. Kildare and made of flow banded rhyolite probably originating from the Tardee area of County Antrim

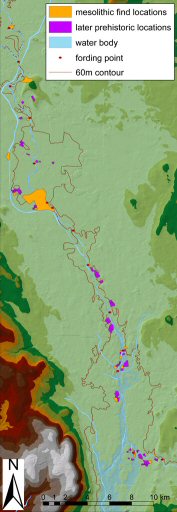

In summary, in the Barrow valley we can recognise different groups of artefacts some of them clearly indicating movement and contacts over substantial distances while others suggest more small scale trips within a rather confined area. However, more interesting still is the fact that all the larger higher quality mesolithic flint objects, as well as the rhyolite one, most likely originating in the northeast of the country, have been found at a select number of locations of higher artefact concentration along the River Barrow (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Middle Barrow Valley study area, showing fording points and prehistoric find locations

All of these locations are positioned close to rock banks in the river which would have formed natural crossing points or fording places in the past. Furthermore they also coincide with locations of confluences between the river Barrow and some of its larger tributaries (Figure 11). It appears therefore as if these locations make reference to the importance of mobility in people's lives, as represented by movements along the courses of the Barrow and its tributaries as well as across them, utilising the fording points. In an area, such as the middle Barrow Valley with relatively few striking natural features, such places would have represented welcome landmarks where people from different parts of the country could have come together. They are locales that emphasise both movement and congregation. Elsewhere (Kador forthcoming) I have argued that the large later mesolithic objects found exclusively at these locations could perhaps have epitomised tokens for contacts and connectedness with people and places in other areas; in particular with locations and communities in those regions of northeast Ireland, where the objects had originated.

Figure 11: The confluence of the River Barrow and the River Greese near an ancient fording point that has produced mesolithic artefacts.

© Internet Archaeology

URL: http://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue22/2/4_2.html

Last updated: Tues Oct 2 2007