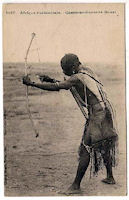

Figure 12: Postcard showing a Mossi warrior wearing some bracelets

Bracelets were sold to the Mossi and Gurunsi in Burkina Faso, and to the Tuareg and Dogon in the Bandiagara area of Mali. The Bozo, settled along the middle course of the Niger, also wore bracelets because 'pour pêcher les poissons au harpon, cela donnait de la force' Trans. 'It gives strength to catch fishes with a harpoon' (Tiemogo). F. de Zelter (1912) tells us that the nomadic fishermen of this ethnic group wore the bracelets above the right elbow, and sometimes on the left arm too. Production for the Mossi, the Dogon and the Bozo was numerically the greatest, the Peul and the Songhaï preferring bronze and silver armlets. In the past, craftsmen also wore their own bracelets (Desplagnes 1907):

'Tout le monde portait des anneaux parce qu'ils savaient qu'avec cela au bras, ils ne risquaient rien'

Trans. 'Everyone wears a bracelet because one knows that, with it on arm, one risks nothing'(Tiemogo).

On the other hand, as the Tuareg dictum says 'quand le bracelet casse, c'est que beaucoup de gens parlent mal de toi' Trans. 'When the bracelet breaks, many people speak ill of one'.

In response to requests from the different ethnic groups, craftsmen produced several types of bracelet. A real competition existed between craftsmen to produce the finest, shiniest and most beautiful pieces. Bracelets were sold or traded for loincloth or cowries (shell money). Broken bracelets would be repaired, and sometimes the fragments were changed into pendants; the magical power of the stone remained the same.

According to Wacaltou and Tiemogo, bracelets for the Mossi and Tuareg were manufactured in the same workshops. All craftsmen were able to produce different types, but those favoured by the Tuareg were the most difficult to make. Roughouts of this type are far less numerous in the workshops because for bracelets the demand stemmed mainly from the Mossi (Pailler 2007).

Most of the production was destined for the Mossi in Burkina Faso (Fig. 12). The bracelets were worn daily by men, whereas women only wore them for protection during the husband's absence. Women's bracelets are the same as the men's; they are elbow bracelets (Pailler 2007). Children could also wear them.

Craftsmen would leave Hombori, alone or in groups, to sell their products to the Mossi. From Hombori, they would cover distances of hundreds of kilometres on foot or on donkey-back to reach the Dogon country, Burkina Faso (Tiebo, Youba, Ouahigouha, Ouagadougou) and Ghana (Boga). They travelled for two or three weeks with loads of several hundred bracelets, which represented several years of work.

After the harvest, once the stores were full, the Mossi organised huge ceremonies during which they 'consumed' large quantities of bracelets. Men and women would pile up many bracelets on each arm to show off their social status and to take part in the ceremony. During the dances they would knock the bracelets together to make a noise and some of them would break. Then they would get new ones from the bracelet makers who were staying in the village. During one ceremony, a person might buy several dozen bracelets. There were also sellers in Ouagadougou who would buy huge quantities from the producers, up to a thousand pieces, and then sell them on. In times of need, the Mossi went directly to Hombori to buy bracelets.

The Tuareg offer a different example of the way in which the bracelets could spread. The Tuareg considers the bracelet, called 'tamtaco', as a weapon in fights or as lucky charms. It is worth remembering that Lhote (1950) noted the war functions that the Tuareg attached to their arm bracelet, and how these related to mythological or imaginary beliefs. In accordance with Tuareg preferences, their bracelets were made exclusively of the Nokema quarry stone which is nearly black (Fig. 13).

The Tuareg came to Hombori to order a bracelet and the craftsman was then able to make one which would fit the arm perfectly; they returned several days later when the bracelet was finished. The parameters of this production are peculiar. The Tuareg, being richer, were asked for more money. In the past, to reduce the cost, they would often finish the polishing themselves; in doing so they were also able to adapt the bracelets perfectly to the size of their arms. In the past few years the manufacture has been accomplished entirely by the craftsman.

Two kinds of bracelet were manufactured for this ethnic group. Some have an elongated section, a bevelled external edge and parallel faces (Zelter (de) 1912); they are very similar to the stone bracelets produced in Western Europe during the Neolithic (Desplagnes 1907, 38). The others appear to have been moulded – moulded bracelets of the same type are known for the Early Neolithic on the Near Eastern sites belonging to the Big Arrowheads Industries (BAI)/Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB), for example at Cafer Hüyük (Turkey) where the earlier stage is dated around 7500-7000 BC (Aurenche and Kozlowski 1999, 159-60, 218) – but this form was probably manufactured only in the Aïr (Lhote 1950). A few fragments of this bracelet type were found during the field survey. They are made of a softer material, quite different from Hombori marble.

Among the Tuareg bracelets are only worn by adults. That worn by the women is called 'mahatila'. It was worn at the wrist and forced on with the aid of shee butter. These bracelets differ in shape to those of the men; they are like those of the Mossi but more massive. Usually a man ordered a bracelet to be given to his wife, but sometimes a woman would ask for a bracelet for her fiancé.

Most of the production now caters only for tourists, with the Tuareg ordering individually. The size of the bracelets was reduced to fit the wrist of European women. Previously they were wider and worn on the forearm or above the elbow. While the bracelets produced for the tourists and the African market are of the same type as those made for the Mossi and the Tuareg, the internal diameter of the tourist bracelet is smaller, around 65mm. The manufacture of thin bracelets designed for western women began during colonisation, with the village chief ordering bracelets from the craftsmen and then selling them to the colonists. Soon afterwards new products appeared, with craftsmen adapting to the demand and also imitating jewellery (rings and pendants) made from agate or cornaline, now executed in Hombori marble. Tontoni himself creates necklaces, earrings and pendants in an innovative fashion.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Europe produced glassy white marbled bracelets, which in colour and shape imitated the Mossi bracelets (Lhote 1950), and exported them to western Africa. It is not known whether this competitive production was successful, but fragments of these bracelets were found during field surveys around the village of Hombori. Similarly, blacksmiths imitated the stone Mossi type in copper, whereas wooden examples were made and worn by the Dogon (Fig. 14).

© Internet Archaeology/Author(s) URL: http://intarch.ac.uk/journal/issue26/12/6.html

Last updated: Wed Jul 1 2009