*Department of Archaeology, University of York, UK. julian.richards@york.ac.uk (0000-0003-3938-899X) / steve.roskams@york.ac.uk (0000-0003-1695-7344)

Cite this as: Richards, J. and Roskams, S. 2013 Burdale: An Anglian Settlement in the Yorkshire Wolds (Data Paper), Internet Archaeology 35. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.35.8

This dataset has been deposited with the Archaeology Data Service. doi: 10.5284/1021540

Referee statement by Gabor Thomas

The Burdale digital archive (Richards and Roskams 2013) comprises a broad range of primary and secondary data derived from fieldwork and post-excavation analysis. It complements the summary report published as Richards and Roskams (2012).

Full stratigraphic reports are downloadable for each season of excavation and can be related to the sequence of CAD plans also available. These can, in turn, be set within the wider site map derived from aerial photography and geophysical survey. Final reports are available for the pottery, spindlewhorls, and worked bone and antler (Ashby 2013). Other finds are simply listed in the finds databases, split by excavation year, with some preliminary notes on the ironwork included in the investigative conservation reports. The non-ferrous finds assemblage was largely missing, apart from a small number of topsoil finds recovered during metal detector surveys. Given the alleged wealth of the site, and the interest in it from 'nighthawks' we have to assume that unfortunately, most of the coinage and copper alloy metalwork has been collected from the ploughsoil over many years and is in private hands or has been sold for profit. In common with other Yorkshire sites Burdale produced very little early medieval pottery but this is likely to be a real absence rather than a product of recovery bias. The animal bone assemblage (Richardson 2010) is one of the most important elements of the archive. Over 300 images are also presented, split by year of excavation.

The file downloads are organised in 3 groups: those relating to the whole project and those specifically related to excavations in 2006 (BUR06) or 2007 (BUR07).

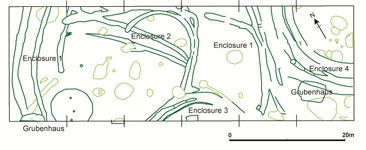

Figure 1: Roman and 'Butterwick-type' settlement enclosures south-east of Burdale House Farm, transcribed and interpreted from aerial photograph and geophysical survey data (reproduced from Richards and Roskams 2012, fig.48, p.114). © University of York. Used with permission.

The Anglian settlement at Burdale (SE 875623) is situated in the main Thixendale-Fimber valley, 2km south-east of Wharram Percy (Wrathmell 2012c). The valley has been subject to metal-detecting over a number of years, mostly illegal 'night-hawking', at the eastern end of the valley away from Burdale House Farm.

The Burdale valley was included within Colin Hayfield's Wharram parish survey, and two sites were identified (Hayfield 1987, 132-44). The first (Burdale Crossroads – SE872623) was investigated on the triangular green formed by the road intersection at Burdale. A sequence of pottery spanning from the 3rd or 2nd century BC to the 17th century AD suggests this was a preferred settlement location, although there is no evidence to suggest it was permanently occupied (Hayfield 1987, 132-7) . A Roman and Anglo-Saxon site became the location of the medieval vill which, following its desertion in the 16th century, became the site of a large post-medieval farm, Burdale House Farm. The majority of this site is overlain by the railway embankment and present-day farm buildings.

Hayfield's second site (B18: Burdale/Fimber Boundary farmstead - SE 881618) is at the other end of the valley (Hayfield 1987, 137-43). Crop marks appeared here in 1976 and were photographed by Tony Pacitto. Hayfield recovered predominantly Roman sherds and concluded that this was another Romano-British farmstead. Given its location, 950m from the Burdale Crossroads site, he observed that it would comply with the general 1km spacing of Romano-British settlements in the Wharram area. It is likely that the current roadway follows the route of a Roman trackway (Hayfield 1987, 195).

From 2005-7 a team from the University of York investigated the Anglian activity at Burdale. The project encompassed a range of desk-based and fieldwork-based activities, as follows:

Figure 2: Panoramic view of excavations in 2006. [View static image] Credit: Ben Gourley CC-BY-NC-SA

The earliest Anglian landscape organisation took place in the 8th century with the laying out of a series of enclosures, in two groups. The enclosures were recut and modified on a number of occasions until the demise of the settlement in the later 9th century. Parts of up to 4 enclosures (1-4) were excavated in the eastern group in 2006, and a further 3 enclosures (5-7) were excavated in the western area in 2007. Within the enclosures there was evidence of both agricultural and light industrial activity and 5 sunken workshops, or Grubenhauser were excavated, as well as traces of a bow-sided hall.

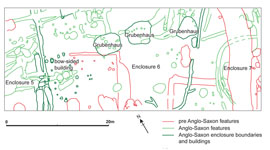

Figure 3: Burdale 2006. Composite phase plan of excavated features (reproduced from Richards and Roskams 2012, fig.49, p.115). © University of York. Used with permission.

In the eastern area the first enclosure (Enclosure 1) was set out in a single development of this part of the site, in the form of three parallel, curving ditches, plus presumed internal banks. The limited depth of the ditches suggests a demarcation of space, rather than defensive mechanism, whilst the southern terminal of the innermost ditch and possible postholes beyond imply an entrance arrangement at this point. The creation of this enclosure, its projected dimensions at least 40m across, clearly represents a major development of the area. A second curvilinear ditch, Enclosure 2, c.20m across, was set inside Enclosure 1, until this was replaced by another internal sub-division, Enclosure 3, c.25m across. Inside the enclosures a series of pits with clay hearths at their base appear to have had an industrial function, whereas other pits may have been used for storage, although they were ultimately backfilled with domestic refuse. Two Grubenhauser were inserted into backfilled enclosure ditches. In the east of the site, another large enclosure, Enclosure 4, was created with the digging of three concentric ditches. Within Enclosure 4, two adjacent pits containing a profusion of charcoal debris suggest production activity, probably associated with a second pair of pits to the north and an adjacent working area. This implies that the new zone was a production space, much as that defined within Enclosure 2 to the west. Finally, south of Enclosure 4, another, even larger, 'production' pit contained a channel and pit with a pebble-lined base. Hence a diagnostically different set of production facilities is implied for this sphere. Overall, a highly structured use of space is indicated in each area lying inside each enclosure or within the interstices between them.

Figure 4: Burdale 2007. Composite phase plan of excavated features (reproduced from Richards and Roskams 2012, fig.50, p.116). © University of York. Used with permission.

In the western area, excavated in 2007, a major late prehistoric or Romano-British boundary ditch ran north-south across the full width of the eastern end of the excavation. Two rectilinear enclosures and associated pits had been built against it in the Iron Age or Romano-British period. The earliest Anglian activity is again represented by three curvilinear enclosures, Enclosures 5-7. Within Enclosure 5, a roughly square structure 3m across was inserted just inside the north side of the entrance, perhaps to monitor movement into that zone, corresponding with a ditch channelling traffic on its south side. Three Grubenhauser were constructed within internal subdivisions of Enclosure 6. The westernmost structure measured c.5 x 4m and was 0.70m deep with a timber framed structure in its base enclosing an area just under 4 x 3m and entrance arrangements along its southern side. Pebble metalling shows that occupation took place in the base of the feature. Immediately to the east, a second building was slightly smaller than its western counterpart but was roughly the same depth and also incorporated a subsidiary area in its base, measuring 3 x 2.5m. The sides of the lower element, in this case, were revetted by planks held in place by posts seemingly separate from the superstructure of the building as a whole. In addition, access was via an entrance arrangement at its south-east corner. Finally, some 6m east of the above structure, a third building, not completely excavated, was set within another subdivision of Enclosure 6. Slightly smaller than its western counterparts, measuring c.4.5 x 2.5m, it also had a subsidiary cut just over 3 x 2m across, perhaps linked to the postholes evident in its sides, and was of similar depth. Its entrance appears to have been on the long axis on its southeast side. Beside the western entrance to Enclosure 6, 14 postholes form a bow-sided building measuring c.8 x 4m. Four other postholes imply a small structure further east. As the bow-sided building lies across the line of the access between Enclosures 5 and 6, it may have acted as a form of gatehouse, controlling movement by making it pass through a roofed area.

Finally, a series of test pits dug to the north of the main excavation area for the purposes of evaluation generated some evidence for activities there. For the most part, this comprised indications of pits, gullies and some larger ditches which would not have been out of place in the fully excavated sequence. However, a number of stone-packed postholes, mostly larger than those seen to the south, and stone footings for a possible masonry wall might imply a more substantial form of structural development here. This, together with the higher proportions of building materials, animal bone and pottery found in overlying strata, imply later medieval occupation, associated with the medieval vill under Burdale House.

Full descriptions of the stratigraphic sequences are available for download in the 2006 and 2007 archives.

The site was selected for further investigation as part of a University of York research project to investigate Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Scandinavian settlement on the Yorkshire Wolds. The objectives of the fieldwork were:

Preliminary reconnaissance, including field-walking and magnetometry confirmed settlement activity. The crop marks indicated two concentrations of Anglo-Saxon activity: the first, at the western end comprised enclosure ditches, trackways and various cut features, possibly buildings. Intercutting features demonstrated that several phases of activity were represented. Magnetometry yielded significant magnetic anomalies in this area, suggestive of intense burning. There appeared to be a gap in activity to the south-east, with no crop marks at the junction of Whaydale and the main valley. Further east, however, there was a second concentration of activity with traces of several 'Butterwick-type' enclosures, as well as more rectangular enclosures, most clearly visible at the eastern end – Hayfield's Burdale/Fimber boundary farmstead. Field-walking and metal-detecting confirmed this twin focus of activity, although there was a background scatter of artefacts across the valley. The soils within the western concentration were much darker and contained more loam. Test pit excavations suggested that deposits were thicker here, and quantities of medieval pottery were recovered, possibly relating to middens associated within the vill underlying Burdale House Farm. Two seasons of excavation were undertaken, on the eastern and western groups of enclosures, in 2006 and 2007 respectively, as student training exercises for the University of York.

The reorganisation of the landscape into a series of curvilinear enclosures seems to have taken place in the first half of the 8th century. The earliest datable Anglo-Saxon finds were a Series D sceatta dated AD 700-715 (BUR07: sf165), and a Series E sceatta dated AD 710-60 (BUR07: sf170). Later finds included a styca of Aethelred II, dated AD 841-4 (BUR07: sf168). Other Anglo-Saxon finds included combs, 8th-century tweezers (BUR07: sf34), copper alloy brooches and dress pins, part of an iron bell (BUR06: sf203) similar in construction to those found at Coppergate (Ottaway 1992, 557) and a wide range of knives, including a leather worker's knife (BUR06: sf215) and a pivoting knife (BUR07, sf235) (Ottaway 1992, 586). A fragment of an Arabic dirham (BUR07: sf27) is also indicative of Anglo-Scandinavian activity. A copper alloy faceted pin head is very similar to dress pins found in Anglo-Scandinavian contexts in York and an iron pin with a polyhedral head (BUR06: sf201) is related to examples found at Coppergate from period 4B (c.930/5-c.975) (Mainman and Rogers 2000, 2577), suggesting that activity may have continued into the early 10th century.

The process of transformation of an enclosed rectilinear organisation of the landscape evident in the Romano-British period and its replacement with a more open landscape and a number of 'Butterwick-type' enclosures sometime in the 8th century is very similar to that observed or implied at Wharram Percy. It is also clear that activity continued into the 9th century, and that there is evidence for Anglo-Scandinavian activity in the same area. However, there appears to have been a complete break in settlement during the 10th century with no continuation of activity on the site of the Anglian enclosures. Nor, as seen at Cottam (Richards 2001), did Anglo-Scandinavian settlement precipitate a short term 10th-century re-organisation. The medieval vill must have been adjacent to Burdale crossroads and today lies under the embankment and Burdale House Farm, although it can never have grown to the size of the village at Wharram and never had its own church.

The Burdale excavations provided the opportunity to sample the interior of a number of the Anglian enclosures. The negative features observed in the aerial photography and magnetometry were confirmed as Grubenhauser and pits. Some of the pits appear to have had an industrial function with hearth bases, and evidence for metalworking. Others may also have had a specialist function originally, but ended up as convenient rubbish pits. The Grubenhauser also appear to have had an industrial function, with activity taking place directly on the sunken floor area, as observed at West Heslerton. Their continued use into the 8th and 9th century has now been observed at a number of East and North Yorkshire sites. There is evidence for the organisation of space both within each excavation site, but also between the two concentrations of enclosures. Clearly both foci of activity were contemporary but they were c.200m apart, with an open area in between them. This zoned use of the landscape parallels that observed at a larger scale at West Heslerton (Powlesland 2003, 289-91). The curvilinear enclosures at Burdale were also reorganised through time. The stratigraphic evidence suggests that the enclosures were laid out first and later sub-divided, in some cases after some of the ditches had already been filled, at least partially.

The nature of 'Butterwick-type' enclosures has been debated. Everson and Stocker (2012) prefer to see them as temporary upland settlements in support of the summer grazing of flocks. They argue that permanent settlement only returned to the Wolds in the 9-10th centuries. Wrathmell (2012a; 2012b) has disputed this, arguing that the Wolds were reoccupied in the 8th century and that the enclosures at Wharram were occupied all year round. The range and intensity of activity at Burdale supports this latter interpretation. It is likely that the Anglian and Anglo-Scandinavian residents of Burdale were in close contact with their contemporaries at Wharram Percy. Indeed the proximity of the sites makes it likely that both were controlled from the same estate centre in the Anglian period, although it is unclear what happened to this relationship with the changes in land ownership which came about as a result of Scandinavian settlement in the late 9th and 10th centuries. There is certainly evidence for some Anglo-Scandinavian activity at Burdale, but the Anglian settlement was abandoned rather than reorganised, and any later 10th century activity must be assumed to be under the medieval vill.

A summary report of the Burdale project has been published as Richards and Roskams (2012). The physical archive has been deposited with Malton Museum. The digital archive is available from the Archaeology Data Service (Richards and Roskams 2013) where it is one of a growing number of archives of supplementary digital material for Anglian and Anglo-Scandinavian sites in East and North Yorkshire, available from the Archaeology Data Service. These include:

| Cottam A | Richards 2011a |

| Cottam B (Burrow House Farm) | Richards 2001 |

| Cowlam | Richards 2011b |

| Wharram Percy | Wrathmell 2012 |

Burdale was also included within the remit of the VASLE (Viking and Anglo-Saxon Landscape and Economy) project (Richards, Naylor and Holas-Clark 2008).

Ashby, S. 2013 'Worked bone and antler' in Richards, J.D. and Roskams, S. 2013 Burdale: an Anglian settlement in the Yorkshire Wolds [data-set], York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. doi: 10.5284/1021548

Bambrook. G. 2005 'Metal detector survey' in Richards, J.D. and Roskams, S. 2013 Burdale: an Anglian settlement in the Yorkshire Wolds [data-set], York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. doi:10.5284/1021545

Charno, M. 2006 'Air photograph transcription' in Richards, J.D. and Roskams, S. 2013 Burdale: an Anglian settlement in the Yorkshire Wolds [data-set], York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. doi:10.5284/1021541

Dobson, S. Gourley, B. Neal, C. and Goodchild, H. 2013 'Field-walking' in Richards, J.D. and Roskams, S. 2013 Burdale: an Anglian settlement in the Yorkshire Wolds [data-set], York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. doi:10.5284/1021546

Everson, P. and Stocker, D. 2012 'Wharram before the village moment' in S. Wrathmell (ed) Wharram: A Study of Settlement on the Yorkshire Wolds XIII: A History of Wharram Percy and its Neighbours, York University Archaeological Publications 15. 164-72.

Gourley, B. 2006 'Geophysical survey' in Richards, J.D. and Roskams, S. 2013 Burdale: an Anglian settlement in the Yorkshire Wolds [data-set], York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. doi:10.5284/1021549

Hayfield, C. 1987 An Archaeological Survey of the Parish of Wharram Percy, East Yorkshire. 1, The Evolution of the Roman Landscape, British Archaeological Reports (British Series) 172. Oxford.

Mainman, A.J. and Rogers, N. 2000 Craft, Industry and Everyday Life: Finds from Anglo-Scandinavian York, The Archaeology of York AY17/14, York Archaeological Trust.

Neal, C. 2006 'Geoarchaeological report' in Richards, J.D. and Roskams, S. 2013 Burdale: an Anglian settlement in the Yorkshire Wolds [data-set], York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. doi:10.5284/1021544

Ottaway, P. 1992 Anglo-Scandinavian Ironwork from 16-22 Coppergate, The Archaeology of York AY 17/6, York Archaeological Trust.

Powlesland, D. 2003 'The Heslerton parish project: 20 years of archaeological research in the Vale of Pickering' in Manby, T., Moorhouse, S. and Ottaway, P. (eds) The Archaeology of Yorkshire: an assessment at the beginning of the 21st century, Yorkshire Archaeology Society Occasional Paper 3. 275-91.

Richards, J.D. 2001 Burrow House Farm, Cottam: an Anglian and Anglo-Scandinavian Settlement in East Yorkshire [data-set]. York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. doi:10.5284/1000339

Richards, J.D., Naylor J. and Holas-Clark, C. 2008 The Viking and Anglo-Saxon Landscape and Economy (VASLE) Project [data-set]. York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. doi: 10.5284/1000044

Richards, J.D. 2011a Cottam A: a Romano-British and Anglian Settlement in East Yorkshire [data-set]. York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. doi:10.5284/1000132

Richards, J.D. 2011b Cowlam: Anglian Settlement in East Yorkshire [data-set]. York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. doi:10.5284/1000175

Richards, J.D. and Roskams, S. 2012 'Investigations of Anglo-Saxon occupation in Burdale: an interim note' in S. Wrathmell (ed) Wharram: A Study of Settlement on the Yorkshire Wolds XIII: A History of Wharram Percy and its Neighbours, York University Archaeological Publications 15. 113-8.

Richards, J.D. and Roskams, S. 2013 Burdale: an Anglian settlement in the Yorkshire Wolds [data-set], York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. doi:10.5284/1021540

Richardson, J. 2010 'Animal bone' in Richards, J.D. and Roskams, S. 2013 Burdale: an Anglian settlement in the Yorkshire Wolds [data-set], York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. doi:10.5284/1021547

Wrathmell, S. (ed) 2012 Wharram: A Study of Settlement on the Yorkshire Wolds XIII: A History of Wharram Percy and its Neighbours, York University Archaeological Publications 15.

Wrathmell, S. 2012a 'Resettlement of the Wolds' in S. Wrathmell (ed) Wharram: A Study of Settlement on the Yorkshire Wolds XIII: A History of Wharram Percy and its Neighbours, York University Archaeological Publications 15. 99-113.

Wrathmell, S. 2012b 'Wharram before the village moment: a response' in S. Wrathmell (ed) Wharram: A Study of Settlement on the Yorkshire Wolds XIII: A History of Wharram Percy and its Neighbours, York University Archaeological Publications 15. 172-3.

Wrathmell, S. 2012c Wharram Percy Archive [data-set]. York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. doi: 10.5284/1000415

On-site direction was undertaken by Steve Roskams, with additional supervision by Madeleine Hummler, Steve Dobson and Ben Gourley. Initial interest in the site was prompted by Cath Neal's doctoral research. Metal detecting support was provided by Mark Ainsley, Geoff Bambrook, Ian Postlethwaite, and colleagues in Historia Detectum. Michael Charno, Eric Thurston and Thomas Mountain provided CAD support. Mags Felter and Ian Panter at York Archaeological Trust undertook the finds conservation, and Tony Austin and Elizabeth Jelley catalogued the finds. Eleanor Blakelock examined the ironwork, and Steve Ashby the bone and antlerwork. Permission to carry out the fieldwork was granted by Lester Bell, tenant farmer, and by the landowner, the Right Honourable Michael Willoughby (now Lord Middleton) and the Birdsall Estate Company.

The fieldwork at Burdale was undertaken as part of University of York training excavations and was funded by the University of York.

Gabor Thomas, Department of Archaeology, University of Reading, UK.

Cite this as: Thomas, G. 'Referee Statement' in Richards, J., and Roskams, S. (2013). Burdale: An Anglian Settlement in the Yorkshire Wolds (Data Paper). Internet Archaeology, (35). doi:10.11141/ia.35.8

The site of Burdale on the Yorkshire Wolds lies within one of the most intensively investigated archaeological landscapes in northern England. In the immediate catchment can be found the internationally important sites of Wharram Percy and West Heslerton, augmented by a cluster of other settlements identified through aerial reconnaissance and metal-detecting of which Cottam and Cowlam have previously been investigated under the ambit of the same University of York project targeting Anglian settlement on the Yorkshire Wolds. The importance of the dataset thus lies in its contribution to a broader programme of research whose cumulative results have the potential to generate something approaching a holistic view of landscape change in an English micro-region over the first millennium AD.

Burdale and other recently investigated sites of similar character have produced key evidence for expansion in settlement and land-use centring on the 8th-9th centuries A.D., demonstrating the intensified exploitation of the Yorkshire Wolds as an upland environment in the so-called Anglian period. The two habitations excavated within the Burdale settlement complex testify to a by now familiar sequence: inception during the 8th century, on sites bearing a strong imprint of Roman habitation and land-use, followed by abandonment in the later 9th century, when a new generation of settlements were established, a high proportion on sites which would endure as medieval nucleated villages. The short-lived nature of Burdale and cognate settlements thus gives direct insight into the later first millennium AD as a period of fluidity and dynamic change in the settlement history of the Yorkshire Wolds.

Burdale has benefitted from two targeted excavations on a reasonably large scale, complementing results gained from a suite of ground-based reconnaissance techniques. The former has provided diachronic insights into the evolving spatial morphology of the settlements concerned, the built environment and aspects of the contemporary economy/lifestyle revealed through the analysis of cultural and bioarchaeological assemblages. This excavated data holds clear potential for wider contextualisation and further study aimed at deepening current understanding of the regional character of the early medieval Yorkshire Wolds both as an economic resource and as a social landscape. In particular, settlements in the Burdale category have much to reveal about the social and economic organisation of upland settlements dependent upon Middle Saxon estate centres located in the surrounding vales. Were these habitations permanently or seasonally occupied? Is it correct to view them as socially impoverished? What role did they play in economic specialisation and supply networks (for example, sheep farming)? And is it possible to discern patterns of interconnectivity linking these communities to each other and to other foci occupying higher rungs of settlement hierarchy? In short, what Burdale and comparative datasets now offer is a rich vein of archaeological evidence for interrogating the mechanics of Middle Saxon estates as economic and social units (Reynolds 1999, 75-84).

On a wider methodological front, the Burdale data also provides a valuable resource for exploiting archaeological approaches as a means to contextualise metal-detected assemblages, including those brought to light by illicit activity. In the early medieval period, so-called Middle Saxon 'Productive Sites' (Pestell and Ulmschneider 2003) represent an obvious target for such archaeological contextualisation. Yet Burdale remains one of relatively few case studies where serious reflection can be given to how ploughsoil assemblages in the 'Productive site' category behave as settlements under targeted schemes of excavation.

November 2013

Pestell, T. and Ulmschneider, K. (eds) 2003 Markets in Early Medieval Europe: Trade and 'Productive' Sites 650-850, Wingather Press.

Reynolds, A, 1999 Later Anglo-Saxon England: Life and Landscape, Tempus.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.