Kent was the first area to fall to the invaders; between 443 and 456 if one believes in the traditional but somewhat questionable Anglo-Saxon Chronicle dates, calculated up to 400 years after the event. The more contemporary Gallic Chronicle of 452 gives a date of 441 for Britain passing into the hands of the Saxons but even this is disputed (Burgess 1990) and, in any case, cannot refer to the whole of Britannia.

The Saxon Shore fort at Richborough was dug between 1922 and 1938 before the advent of modern archaeological techniques but examination of the site notebooks and surviving pottery, coupled with my unpublished cataloguing for English Heritage of the 10000+ metal, bone and other objects found there has enabled a tentative reconstruction of events at the fort during the early 5th century. The revelation of the presence of early 5th-century dated base issues in among the 22,750 Theodosian coins from the site means that the sack of the fortress, dated by me in an earlier publication to 410 (Lyne 1999a), should now perhaps be associated with events during the mid-5th century.

There is some evidence that early 5th-century occupation at Richborough was not of a normal military nature, in that one of the few late stone buildings within the fort (the 'Chalk House') had been demolished and firing of handmade grog-tempered wares (LRGR) carried out on a cobbled area laid over its levelled foundations (Lyne 1994, 435). A very late pottery assemblage from the outer defensive ditch on the south side of the fort may date to after the pottery supply had largely or entirely terminated (Lyne 1994, 445-6). Its overwhelming domination by very high percentages of Oxfordshire finewares (OXRS), which would be expected to have a longer life in use than coarse kitchen crockery, suggests total pottery loss and the onset of an aceramic society.

Richborough appears to have had a violent end: there is evidence for buildings within the fort being burned down and there was a concentration of iron arrowheads, spear heads and knives in and around the ditches outside its west gate. Some of the projectiles had their points turned over or were buckled where they had struck the wall of the fort and bounced off (Lyne 1999a, fig. 2). Pit 314 inside the fort contained the remains of a man, woman and child who had been roughly tipped in together with two trinket boxes, a collection of copper-alloy armlets and rings, a beaten-in shield boss and what may have been an iron helmet (Lyne 1999a, 283-4). Fragments from other trinket boxes with forced locks from the fort ditches and on the road surface inside the west gate hint at looting by the attackers.

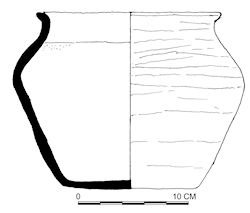

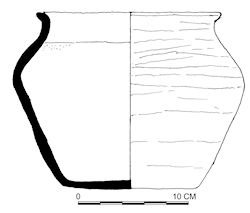

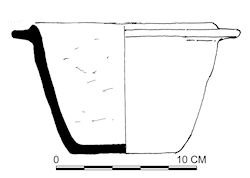

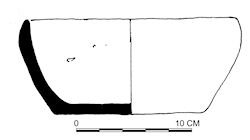

There is evidence for the production of late handmade grog-tempered wares (LRGR) at both Canterbury and Richborough (Lyne 1994, Industry 7B) in a limited range of forms, comprising a simple everted-rim cooking-pot, a deep convex-sided dish and a distinctive beaded-and-flanged bowl form (Figs 1-3). Flasks and handled jugs (Lyne 2010, fig. 54, 170) are also occasionally found and a closed form sherd from Ickham bears an appliqué face with long hair in a style similar to that of the royal bust on the later gold ring of Childeric (Lyne 2010, fig. 54, 178).

These late Roman handmade grog-tempered ware (LRGR) producing pottery industries appeared in East and West Kent and the Hampshire Basin around 250-270. To begin with, they were fairly insignificant but form much larger elements in pottery assemblages of late 4th-century date when the output of many of the producers of wheel-turned greywares started to decline and in some cases ceased.

The grog-tempered wares (LRGR) produced in East Kent account for nearly 70% of the pottery in some post-370 pottery assemblages from Canterbury dating to after the collapse of the Thameside greyware industries (Pollard 1995, 717). These wares are, however, rarely found west of the River Medway. In the last few years, however, examples of the distinctive beaded-and-flanged bowl type have turned up in potentially 5th-century contexts at Tabard Square (Killock et al. 2015, 122) and Guy's Hospital in Southwark (Taylor-Wilson 2002, 37-38) across the River Thames from the walled city of Londinium Augusta. Another example comes from 5th-century occupation within the walls of Verulamium (Lyne 2006, fig. 34-9), well outside the late 4th-century trading area for such pottery. It is striking that other pottery industries, such as those at Alice Holt in Hampshire and Harrold in Bedfordshire, also appear to have greatly expanded their marketing zones towards the end of the 4th and into the early 5th century (Lyne 1994, 502-5), although the quantities of pottery concerned are very small. The long-distance distribution of these wares might be a consequence of the disappearance of local production allowing distant kilns to supply new areas and this might explain why grog-tempered wares from East Kent were now getting as far as Verulamium.

Some short-lived buildings were found constructed along the west side of a late street at the Whitefriars site in Canterbury. The occupation of these structures seems to have started during the early years of the 5th century when only the local handmade grog-tempered wares (LRGR), Alice Holt/Farnham greywares , Overwey/Portchester D (PORD) and Oxfordshire Red Colour-coat (OXRS) wares were still readily available, and continued into a time when old pots and kiln wasters were being salvaged for use in the absence of any other pottery. Much of the latest pottery from these structures is abraded and residual but the fresher fragments include a complete handmade convex-sided dish kiln waster in grog-tempered ware with a wide split in its side extending to the centre of its base (c. 360-420+) and a number of sherds from an underfired early Roman c. 70-150 dated kiln waster flagon (Lyne forthcoming a).

Excavations in 1972-75 at Ickham, between Canterbury and Richborough, revealed evidence for a late Roman industrial site with four successive water-mills and indications of metalworking. Mill 3 was probably constructed after 390 and Mill 4 during the early 5th century (Bennett et al. 2010). There was a large 11kg pottery assemblage associated with Mill 3, with handmade late Roman grog-tempered ware cooking-pots, bowls and dishes accounting for 40% of it, Alice Holt/Farnham industry grey wares for 4% and Oxfordshire Industry finewares (OXRS) and mortaria for 30% (Lyne 2010, 104). The 167 items of metalwork associated with this pottery assemblage include two fragments from copper-alloy foil appliqué crest-holders similar to others from the fort ditches at Richborough and thought to have been attached to very late Roman or even sub-Roman leather helmets (Lyne 1996, fig. 2; Mould 2010, fig. 68). Three lead-alloy pendants decorated in the style of proto-bracteates were associated with these foil fragments and are regarded as being of early 5th-century date (Henig 2010, 190): five similar pendants came from post-370 contexts elsewhere on the site.

Mill 4 is thought to have replaced Mill 3 on a new water channel during the early 5th century and had a mere 47 sherds of pottery, six metal and glass objects and twenty iron nails associated with its earliest phase (Lyne 2010, 109): the pottery can be dated no more closely than c. 300-400+ but the glass is of late 4th to early 5th century date. At some time later the mill-race channel was recut. The 94 sherds of pottery associated with the construction and usage of this rebuilt mill (Lyne 2010, 117) come from comparatively few vessels but include those from four bowls and jugs with handles. One of these is in late Roman handmade grog-tempered ware, two in stamped Oxfordshire Red Colour-coat fabric (OXRS) and the other is a greyware import from north-eastern Gaul, paralleled in a c. 350-420 dated context at Tournai (Lyne 2010, fig. 54, 170, 176 and 174). Such handled bowls and jugs are very rare on late Roman sites: it is even more unusual to have four from different sources associated with one feature and it may be that they were used to measure out grain brought to the site for milling. The upper fill of the abandoned mill channel produced a further 59 sherds including those from another handled bowl in Oxfordshire Red Colour-coat fabric (OXRS) (Lyne 2010, fig. 54, 175), an unparalleled deep convex-sided dish in handmade fine-sanded greyware with random internal burnished decoration (Lyne 2010, fig. 54.176) and an Early Saxon cooking-pot in sandy black fabric (Lyne 2010, 118).

It seems likely therefore that Romano-British pottery, both locally made and imported, continued being used in Kent in decreasing quantities until at least 430. The following 10 to 20 years saw manufacture cease, with the careful curation of some vessels continuing and pots being salvaged from old kiln sites, cemeteries and elsewhere for use in what was an increasingly aceramic society.