Robinson and Wallis (1975, xvi) show that subscription lists provide an 'unmatched source to the interests and tastes of a large section of the population in the last three centuries', arguing that 'no biography of any individual will be complete unless it pays attention to his subscriptions' (Wallis 1974, 270). The potential of subscription lists has been demonstrated through a wide range of scholarship in many disciplines (e.g. Sweet 1997; Holmes 2009). Subscriptions to archaeological societies and journals have provided important insights regarding the social and professional background and affiliations of subscribers, but there is considerable potential for further study (e.g. Ebbatson 1994; 1999; Wetherall 1998; Hingley 2007). The majority of volumes on archaeology in the nineteenth century were published through subscription and there is an immense body of data available, much of which is now easily accessible due to digitisation.

Subscription publishing was an important means of sharing the financial risk associated with publishing ventures, but first it was essential for the author to convince potential subscribers of the value of the work. Proposals might be circulated through advertisements in newspapers, periodicals or books, and through booksellers and personal connections (Sweet 1997, 30). As noted previously, the lists themselves provided an important opportunity for self-promotion, or 'special puffs' such as titles, numbers of copies, qualifications and honours (Wallis 1974, 257). Lists in this period usually followed a standard format and included name, title, qualifications and address/es. They might also include institutional affiliations and memberships, honours and profession.

The information in Table 1 has been entered as recorded in the list of subscribers to 11 of Smith's volumes on the archaeology of Britain, with the addition of information regarding counties and regions. Historic counties have been used, with the exception of London addresses, where it was not always possible to identify postal districts. For the purpose of highlighting general trends, the following rules have been applied: some subscribers list both county and London addresses; in this event the county address has been taken as the primary address. Where subscribers record different addresses in different volumes, the primary address is taken as that listed first chronologically and/or the most frequently listed. Titles and qualifications are recorded as listed (e.g. with French titles sometimes anglicised), with the exception of 'Esquire', which is used by the majority of subscribers and was widely assumed in this period: although it is important to bear in mind that this could be seen as a claim not to be in 'trade' (The Penny Cyclopaedia 1837, IX, 13). Additional columns have been added to provide further insights (e.g. university and museum posts, and whether the individual has an entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography). While the tables generated are somewhat oversimplified, they nevertheless provide an overview of Smith's networks, including regional support, institutional subscribers, titles and qualifications (as listed), and in some cases professional background. They also provide important insights into which of these aspects were deemed most worthy of promotion.

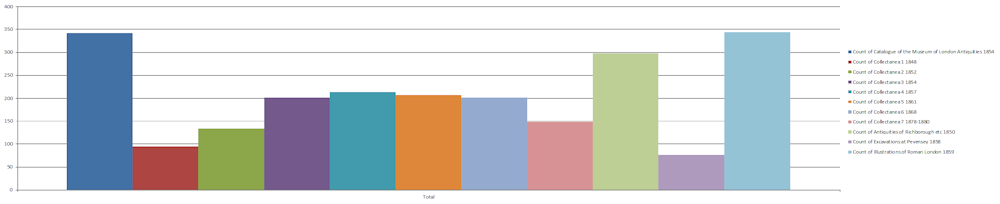

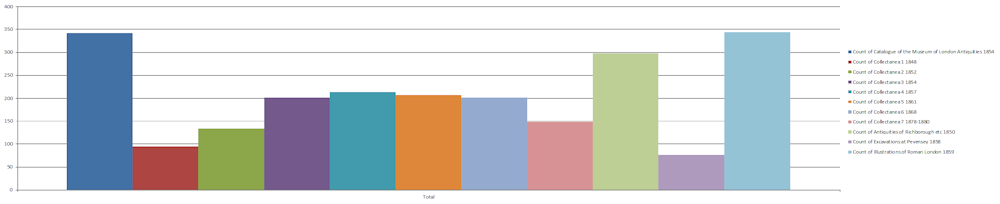

Table 1 lists 899 subscribers for the 11 volumes. The volumes attracting the highest number of subscribers are Illustrations of Roman London (344) and Catalogue of the Museum of London Antiquities (342). The Antiquities of Richborough is in third place with 297 subscribers (see Figure 4; Table 2). Collectanea was not limited to subscribers until volume III, when the numbers increased to 200 or more until volume VII (148). There were 46 female subscribers (5% of total subscribers). Ninety six (approximately 10%) of the subscribers identify themselves as clergy (Table 3). This figure is double that of the BAA, but is significantly less than the 274 (28%) of the AI in 1849 (see Wetherall 1998, 34 for BAA and AI; see Hingley 2007, 176 for membership of the Society of Antiquaries by social categories).

The listing of memberships and affiliations was a common method of asserting the social and intellectual credibility and connections of both authors and subscribers in this period and, as noted by Effros, served to document and celebrate the scholarly achievements and accolades of individuals and groups (Effros 2012, 85). It is evident here that subscribers valued their membership of longstanding institutions: 202 (22.5%) subscribers to Smith's volumes recorded their fellowship of the Society of Antiquaries, a considerably higher number than amongst the BAA (76 (17%) in 1849/1850) or the Archaeological Institute (83 (8%) in 1849) (Table 4) (see Wetherall 1998, 33–34 for BAA and AI figures). Forty six (5%) list fellowship of the Royal Society and 24 (2.6%) of the Royal Geographical Society) (Table 4). Membership of such institutions clearly remained an important marker of social and intellectual standing, despite widespread criticism of the Society of Antiquaries amongst Smith's close circle. The perceived importance of Smith's work to those from a broad social and intellectual spectrum is evident. While usually more closely linked with the BAA rather than the 'more aristocratic' AI (Briggs 2009, 226; see Ebbatson 1999 on the AI), in many ways he appears to have bridged the divide. Interestingly, very few subscribers record their membership of either the BAA or the AI (Table 6).

Other memberships listed can be seen in Table 5, which includes membership or fellowship of national and foreign archaeological and/or scientific societies, such as the Linnean Society and the Numismatic Society. As at the turn of the century, many of those with interests in archaeology were polymathic; indeed, some of Smith's friends and associates, such as Dawson Turner (The Athenaeum, 17 July 1858, 1603, 82; Smith 1868, 314–19) and Frederick Perkins, had been active within Joseph Banks' social and intellectual circle, which played a formative role in the development of archaeology in the early part of the nineteenth century (Scott 2013a and 2014).

French societies listed include the Imperial Society of Emulation of Abbeville, the Society of Antiquaries of the Morini, Saint-Omer, the Society of Antiquaries of Normandy, the Société des Antiquaires (sic) de l'Ouest and the Institute of France (Table 7). The French societies were admired by Smith and his associates (Smith 1851, 3; Effros 2012, 59–87), who were critical of the superficiality of the Society of Antiquaries' continental links. Indeed, some English subscribers list only their membership of French societies; for example, Thomas Wright and Alfred Dunkin, both key figures in the BAA.

It is notable that several of Smith's most generous supporters list membership of the Numismatic Society amongst their associations (e.g. Corner, Mayer, Wright, Evans) (Tables 8 and 13); a symbolic statement of affiliation and 'professional' links (see Effros 2012, 70 on situation in France). Smith and his close associates, most notably Akerman and Evans, believed that numismatics was not taken seriously enough by the Society of Antiquaries and were founder members of the Numismatic Society (Smith 1878–80, 256). Smith asserts that coins combine:

…the claims of sculpture and painting, equally rich as gems of art, and as historical pictures, showing, within the smallest compass, the fullest view of ancient times we possess (Smith 1850/2, 116)

He was awarded the first medal of the London Numismatic Society in 1883 for his work on Romano-British coins (Illustrated London News, 30 Aug. 1890; see Rhodes 1991 on Smith's pioneering work on the Roman coinage from London Bridge). That numismatics was increasingly seen as a distinct field of study can be seen in J. R. Smith's publishing catalogue, included at the back of Akerman's (1844) volume, where volumes on History, Archaeology and Numismatics are listed separately (see Schlanger 2011 on Evans and the emergence of numismatics).

Also significant is the number of overseas subscribers listing official archaeological positions (Tables 9 and 18); for example, Professor and Royal Inspector of the Ancient National Monuments of Copenhagen (Worsaae), Inspecteur des Monuments Historiques de la Seine-Infériure (Cochet), Homme de Lettres, Officier de la Légion d'Honneur (Belloquet) and Director of the Imperial and Royal Ambras Museum of Antiquities (Arneth). This evidence of international recognition from eminent 'professional' archaeologists was undoubtedly key in establishing and cementing Smith's reputation as an expert, and provided a valuable opportunity for them to engage with a wider British audience (see also separate lists of foreign correspondents in the lists of subscribers). Access to comparative material was an increasing concern of British and continental archaeologists: 'In France the abbé Cochet has set an example to his countrymen by the assistance he has gained from our publications' (Smith 1861, v–vi).

The number of female subscribers to Smith's volumes is small but very significant since, during this period, female membership of societies was rare (Anna Gurney became the first female member of the BAA in 1845) (Hoare 1858, 187–89; Smith 1998, 37–69) (Table 10). These listings presented an important and rare opportunity for inclusion and self-promotion (see Hingley 2007 on class and gender in the Society of Antiquaries; see Effros 2012, 69 for the situation in France). A significant number of women subscribed independently of their husbands: for example, Mr and Mrs Dawson Turner and their daughter are listed separately as subscribers to Illustrations of Roman London (Fraser 2004) (Table 1); his wife and daughters provided illustrations and other forms of support for Turner's publications and projects (Smith 1883, 236, 241). His library of more than 8,000 volumes is described as containing:

copies of the best antiquarian and topographical works in English literature…many of the works being large-paper copies. The volumes were, moreover, enriched by drawings and etchings by the late Mrs Dawson Turner and the Misses Turner (The Athenaeum, Jul 17, 1858, 1603, 82)

Amongst Smith's female supporters were notable writers and scholars. Anna Gurney (1795–1857), was a renowned scholar of Old English and the half-sister of Hudson Gurney (Gentleman's Magazine, Sep 1857, 342; Literary Gazette, 4 July 1857, 2111, 342), who was very active in archaeological circles. In addition to her scholarly pursuits she was a progressive educator and was well known for her many and varied philanthropic activities; more than 2,000 people attended her funeral.

Eliza Meteyard (1816–79), a close friend of Smith's, was a prolific writer of novels, a contributor to many periodicals, including The Reliquary, and an advocate of women's rights (The Academy, 12 Apr. 1879, 362, 325; Smith 1886, 106–12; see Beetham 2015, 206–20 on women and periodical writing). She was an active member of the radical Whittington Club, founded by Douglas Jerrold, which admitted women (Kent 1974, 36–37). She was also a noted expert on the life of Josiah Wedgewood (Meteyard 1865). She was interested in archaeology, and published Hallowed Spots of Ancient London in 1862; a guide to historical sites 'Presenting a vast number of curious facts relating to its churches and chapels, its halls and streets, its prisons and houses, as also the lives who hallowed them' (Meteyard 1862, vii; for reviews see Eclectic Review, Apr. 1862, 2, 366 and Gentleman's Magazine, Mar. 1862, 212, 348). The volume is dedicated to Smith, who was a key supporter of hers:

To Charles Roach Smith Esq. FSA. Author of 'Illustrations of Roman London', 'The Antiquities of Richborough, Reculver and Lymne' etc etc etc. In testimony of lengthened friendship, as well as literary obligation, this book is inscribed by his most sincere friend, Eliza Meteyard (1862).

In return for his support, she helped to publicise Smith's works:

In the little book I have been finishing, I have taken leave to mention you and the Inventorium Sepulchrale. It is but a mention; still, as thousands of the book will be circulated, it may make your labours known, and next month when I sit down quietly to my antiquarian work, you, and what you have done so well for the Faussett MSS, shall have my first care (letter to Charles Roach Smith, June 16 1857, in Smith 1886, 107)

Notable female support for Smith can be also be seen through additional financial contributions to his projects: for example, Mrs John Charles of Chillington House, Maidstone is thanked for her donation of £50 towards the cost of publishing Collectanea IV (1857, vii; see Gentleman's Magazine, Sept. 1855, 325–26 for obituary of Thomas Charles); Susannah Charles was the sister-in-law of Thomas Charles and an executor for his estate, which included a museum of 'minerals, fossils, Roman and other pottery, coins, curiosities, and articles of virtu' which he wished to be permanently preserved for the people of Maidstone (Gentleman's Magazine, Sept. 1855, 326; Smith 1883, 141–46).

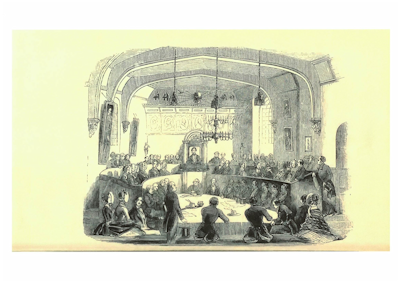

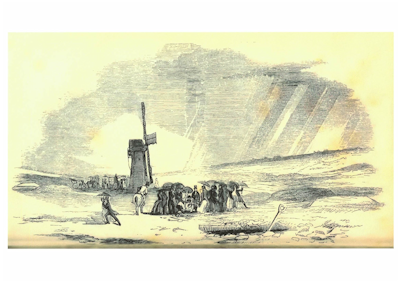

That many women were enthusiastically engaged in archaeological pursuits is clear from illustrations (Figure 5) and descriptions of activities which took place at the Canterbury Congress of the British Archaeological Association in 1844. One incident involved Mrs Pettigrew (wife of the BAA treasurer Thomas Pettigrew) who, together with a group of women, visited nearby excavations of Anglo-Saxon barrows on Breach Down (Figure 6); the women were offered shelter in a windmill during a heavy rain shower, but declined because 'the loss of a dress, which could easily be replaced, was of trifling consideration compared with the equally interesting and instructive researches in which they were engaged' (Dunkin 1845, 93; Moshenska 2012).

Smith acknowledges many women who supported archaeological projects and publications, and in return he provided support and encouragement for their various projects. These 'hidden' contributions have received little attention in histories of archaeology, which have tended to focus on women whose exploits and interests most closely approximate those of men, with an emphasis on exoticism and adventure (for e.g. Classen 1994; Díaz-Andreu and Sørensen 1998; Cohen and Sharp Joukowsky 2004 for critique; see also Levine 1987; 1990; Smith 1998; Browman 2013; see also https://digventures.com/2015/03/pioneering-women-in-archaeology/ and http://trowelblazers.com/ for women in archaeology). The value of a more prosopographical approach is clear, and book subscription lists are an under-utilised resource in this respect.

Subscribers were largely based in England (803), but with significant numbers from other regions of the United Kingdom (Scotland 24, Wales 8, Ireland 9); Europe, most notably France (22), Germany (7), Denmark (2) and Switzerland (2); and from further afield: USA (3), Australia (3), and Canada (2) (Table 11). Smith had personal connections with a number of the overseas subscribers: for example, his brother-in-law Colonel Joliffe and his nephew William Joliffe (Smith 1883, 99; 102; 126; Smith 1891, 154–57). French subscribers and correspondents include the President of the Academy of Sciences, Arts and Belles Lettres of Caen (Charma), President of the Imperial Society of Emulation of Abbeville (Boucher de Perthes), President of the Société des Antiquaires (sic) de l'Ouest (Dupont) and the President of the Society of Antiquaries of the Morini, Saint-Omer (Hermand). Smith visited France on several occasions and regularly corresponded with French archaeologists (see, for example, his obituaries of Monsieur de Caumont (Smith 1874; Schnapp 1996, 280) and the abbé Cochet (Smith 1875; Effros 2012, 153; Smith 1883, 196–296 on visits to France)). He successfully campaigned with the abbé to persuade Napolean III to save the Roman walls of Dax (Smith 1891, 50). He also developed a close relationship with M. Boucher de Perthes at Abbeville (Smith 1861, ix; Schnapp 1996, 312–13, 371–73). He describes their relationship in Retrospections II:

we were in constant correspondence; and he visited me during the Great Exhibition. Not only did he supply me with his publications, but he sent them to all the Societies with which I was connected, and to my private friends (Smith 1886, 138)

Boucher de Perthes' pioneering work establishing connections between flint tools and extinct animals was initially ridiculed, but subsequently verified by Evans and Lyell (see below) amongst others (Smith 1861, ix). Smith asserts that 'the triumph of science over prejudice and incredulity will be hailed by all lovers of truth' (Smith 1861, ix). Their relationship was mutually beneficial: Smith publicly supported his work at a time when many scholars were resistant to the notion of prehistory, while in return he provided Smith with information, publications and promoted his work to a French audience (Rowley-Conwy 2007).

The two Danish subscribers were Thomsen and Worsaae, the eminent Danish archaeologists. Worsaae visited London in 1846 (The Academy, 29 Aug. 1885, 140; Rowley-Conwy 2007, 108; Wilkins 1961), in the midst of squabbling between the Association and the Institute. While Worsaae was generally unimpressed by archaeologists in London, he corresponded regularly with Smith, whose support he acknowledges:

Amongst the many gentlemen to whom I owe my thanks, I must particularly name: Sir H Dryden, Bart. Of Canons Ashby; C. Roach Smith Esq., FSA, London; E. Hawkins Esq, British Museum; J. M. Kemble Esq; Professor Cosmo Innes, Edinburgh; Dr Trail ibid.; C. Neaves Esq. ibid.; R. Chalmers Esq. of Auldbar Castle; Rev. J.H. Todd, DD, Trinity College, Dublin; Professor C. Graves; and Dr G. Petrie, likewise of Dublin (Worsaae 1852)

The majority of English subscribers (33%) were London-based (292), but a number of counties had significant numbers of supporters: Kent (112); Yorkshire (39); Hampshire (38); Sussex (35); Norfolk (27) and Lancashire (27) (see Table 12). Twenty seven subscribers listed both London and county addresses. Those counties with large numbers of subscribers were those that had particularly active archaeological societies, such as London and Middlesex, Yorkshire, Sussex, Newcastle upon Tyne, Norfolk, Lancashire and Cheshire and Kent (see Levine 1986, appendix IV; Hoselitz 2007, 19–22; Wetherall 1998; see also Sweet 1997 on the importance of urban histories for local pride and patriotism). For example, the vice-presidents of the Norfolk and Norwich Archaeological Society (1847) include Sir J. P. Boileau (Gentleman's Magazine, May 1869, 2, 746), Hudson Gurney (Smith 1868, 319–23; 1883, 242–45; Gentleman's Magazine, Jan. 1865, 1, 108–9), Daniel Gurney and Dawson Turner (The Athenaeum, 17 July 1858, 1603, 82; Smith 1868, 314–19), all of whom were generous supporters of Smith's volumes. Smith is listed as an honorary member of the Society. The significant number of subscribers from Hampshire (which encompassed the Isle of Wight) and Kent is not surprising, given Smith's roots and connections. William Henry Rolfe of Kent was one of his closest friends and supporters, and Smith retired to Strood, Kent (Smith 1883, 1–8). These networks of support merit further investigation as they were critical to the dissemination of archaeological knowledge in this period.

Smith's most generous supporters (ten volumes or more), all of whom he acknowledges in his Retrospections, were John Collingwood Bruce (Smith 1883, 170); Joseph Clarke (Smith 1883, 8, 12, 153); George Richard Corner (Smith 1868, 324–26); John Evans (Smith 1891, 126–31); James Cove Jones (Smith 1883, 245); Joseph Mayer (Smith 1883, 67–76); Revd Beale Poste (Smith 1886, 15–19); Edward Pretty (Smith 1883, 146–47); William Henry Rolfe (Smith 1883, 1–8) (subscribed to all 11 volumes); John Green Waller (Smith 1886, 20–31); Charles Warne (Smith 1883, 85–87); Humphrey Wickham (Smith 1883, 127); Thomas Wright (Smith 1883, 81–85); and Albert Denison Conyngham (Smith 1883, 162–69) (Table 13).

As noted above, a key subscriber and generous supporter of Smith's was Joseph Mayer (The Reliquary, Apr. 1886, 26, 226; Smith 1883, 67–76). Mayer was born in Newcastle under Lyme, Staffordshire, attended Newcastle under Lyme Grammar School, and developed a passion for archaeology and collecting as a child. He became a highly successful jeweller and goldsmith, running his own business from 1844, and became a leading benefactor of education and the arts. While he is perhaps best known for his purchase of the Faussett Collection (White 1988, 121), he was committed to the development of national art and archaeology (Mayer 1876). For example, he supported many publication projects, such as Wright's Feudal Manuals of English History (1872), Meteyard's Life of Wedgewood (1865) and Thorpe's Diplomatorium Anglicum Aevi Saxonici (1865), and donated his substantial collection of art and antiquities to the City of Liverpool. He is described as a 'true lover of archaeology, and munificent patron of Art and literature' (The Reliquary, April 1886, 26, 226). He was similarly generous in celebrating the achievements of his friends through commissioning busts, medallions, paintings and photographs, which were 'liberally distributed by him' (The Reliquary 1886, 26, 226); a topic which merits further study. He met Smith at the Chester conference of the BAA and they developed a close friendship (Smith 1883, 67–76).

In addition to subscriptions, Mayer provided many contributions to Smith's projects, such as £25 towards the cost of Collectanea IV (1857, vii), £20 for Collectanea V (Smith 1861 x) and £10 towards volume VI (1878–1880, vii). He is recorded as providing 'substantial sympathy' and 'substantial pecuniary help' for Collectanea III (Smith 1854b viii) and VII (Smith 1868, vii). He also paid 200 guineas to Smith for his work on the publication on the Faussett Collection. In return, Smith was instrumental in helping Mayer to establish his impressive collections through his British and overseas connections (White 1988, 131; Tythacott 2011); Mayer greatly valued these connections, and the subsequent recognition that he gained. In the subscription lists he records his membership of the Numismatic Society, the Society of Antiquaries of Normandy, the Société des Antiquaires (sic) de l'Ouest, and his fellowship of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, in addition to his fellowships of the Society of Antiquaries of London and the Royal Society. The association with new and more 'scientific' organisations made an important statement about his connections and ambitions at a time when a background in 'trade' could result in marginalisation within long-established institutions (Hingley 2007, 174–78; Hoselitz 2007, 71).

Sir John Evans (1823–1908) (Smith 1891, 126–31; MacGregor 2008a and b) also worked closely with Smith, and subscribed to ten of the eleven volumes. Alongside his exceptional achievements as a leading paper manufacturer, Evans pursued his archaeological and numismatic interests at every opportunity; he also developed an interest in geology through investigating the water supply for his paper mill. He became a close friend of the geologist Sir Joseph Prestwich (1812–1896), with whom he visited Jacques Boucher de Crèvecœur de Perthes in 1859. He developed an expertise in river gravels and cave deposits, and was instrumental in validating the revolutionary discoveries of the French archaeologist. He subsequently played a key role in national institutions, including the Society of Antiquaries of London, the Royal Society, and the Numismatic Society, and was a Fellow of the Geological Society from 1857; he was awarded the Lyell Medal for services to geological science in 1880. Perhaps most significant here, he was one of the first men with a background in trade to be elected FRS (1864) (he became Vice-President in 1876). In the lists of subscribers, Evans records his fellowships of the Royal Society and Society of Antiquaries, his connections with the Numismatic Society (member and Vice-President), as well as his honorary LLD (Dublin), one of many honours that he was awarded (Foote 2004). Evans' recognition of the importance of Smith's work is clear in The Coins of the Ancient Britons [sic] (Evans 1864, 207; 353; 350 15; 245). It is also evident that Smith provided significant support in kind for Evans' projects:

Mr C. Roach Smith, who not only furnished me with a large number of casts of British coins, and with notes as to the places where they were found, but also presented me with several scarce coins, and aided me in procuring others (Evans 1864)

Their relationship was mutually advantageous.

Smith's supporters also included those who made a living from archaeological writing (Akerman and Wright), which was rare in this period. Thomas Wright's significant investment in Smith's work (ten of the eleven volumes) is notable, given his frequently precarious financial situation. He was the son of a bookseller and printer (his father wrote the History and Antiquities of Ludlow in 1822 (2nd edition 1826) and studied at Trinity College, Cambridge (BA 1834; MA 1837) where he developed an interest in vernacular sources (Art Journal, Mar. 1878, 75; The Reliquary, Apr. 1878, 18, 255; Illustrated London News 12 Jan. 1878: 42;). He was a regular contributor to many popular periodicals, and played a lead role in the establishment of a number of archaeological and literary societies. He was elected to the Society of Antiquaries in 1837, supported by a number of eminent medievalists and folklorists, and was an acknowledged expert on French history and antiquities. He was chosen by the Emperor Napoleon to translate into English his Vie de Jules César (Art Journal, March 1878, 75). He published prolifically, often collaborating with Fairholt, and relied heavily on patronage; Mayer was a key supporter of his. He worked closely with Smith from the 1840s (Smith 1883, 76–85), and together they founded the British Archaeological Association. However, Wright's work was not viewed favourably by many of those who subsequently formed the Archaeological Institute (AI), most notably Albert Way, who was reported as being jealous of Wright and his Archaeological Album (Lloyd's Weekly London Newspaper, 8 Mar. 1845, 120; Briggs 2009, 213; Ebbatson 1994; 1999). In contrast, Smith was an enthusiastic supporter of Wright's work; for example, providing a glowing review of his Album in the Journal of the British Archaeological Association (Smith 1845, 1, 269–71). Wright, in return, is full of praise for Smith's work:

The best collection of antiquarian materials we possess at present is the Collectanea Antiqua by Mr Roach Smith, which, however, is already becoming rare. Many good papers on primeval antiquities, by Mr Roach Smith and others, will also be found in the volumes of the Journal of the British Archaeological Association, and in the Archaeological Journal published by the Archaeological Institute (Wright 1852, ix).

The importance of Smith's support, in the form of knowledge, materials, reviews and access to intellectual and social networks, was of the utmost importance to those attempting to publish their work on British history and archaeology during this period. Many of his most generous supporters were indebted to him for their own publishing ventures; for example, Beale Poste and John Waller were both supported by Smith, as acknowledged in their volumes (Waller and Waller 1864; Smith 1886, 15–19; 20–31).

It has been argued that the BAA was less 'academic' and less 'aristocratic' in its makeup than the AI (Briggs 2009, 217; Wetherall 1998, 34); however, Smith's supporters included academics, museum professionals, members of the aristocracy, and members of both societies. A significant number were university educated (12% list their qualifications) (Table 14), and a number held key positions in national museums and institutions (Table 9).

Notwithstanding his background in 'trade', his association with individuals whose activities attracted considerable criticism amongst the establishment in the 1840s (most notably Thomas Wright and Thomas Pettigrew), and his frequent challenges to those in positions of authority, Smith cultivated and sustained friendships with influential members of the aristocracy (Table 15). Albert Denison, Lord Londesborough (Smith 1883, 162–69), became a close friend and supporter of his projects. Smith records that he 'offered to build me a house that I might be near him at Grimston'. He also offered a cheque for £3,000 for Smith's Museum (see below).

It is clear from the biographies of numerous subscribers that many were nonconformist, philanthropic, and at the forefront of educational and social reform during this period (Table 19). For example, John Kenrick was acknowledged as 'Indisputably the greatest nonconformist scholar of our day' (The Times, May 7, 1877). The eminent geologist Sir Henry Thomas de la Beche (Portlock 1856, xxxiv–xxxviii) was vehemently opposed to all kinds of aristocratic privilege, while William Henry Blaauw (Campion 1870) helped to build links between the Sussex gentry and archaeologists from professional backgrounds, such as Mark Lower. Notable philanthropists included Henry Dodd, George Gibson, Apsley Pellatt and William Devonshire Saul. Smith's networks and projects were therefore important contexts in which social inequalities were challenged, with an increasing emphasis placed on the importance of specialist knowledge over aristocratic privilege. The key role that he and many of his friends and supporters played in social and educational reform is reflected in the fact that 214 (24%) of his subscribers are recorded in ODNB, a 'national record of men and women who have shaped British history and culture'.

A number of subscribers held key positions in national institutions (Table 9). For example, Edward Hawkins and Augustus Franks, at the British Museum (Caygill and Cherry 1997), supported Smith's campaigns and benefitted from his knowledge. Franks played a key role in securing Smith's collection for the British Museum, and Smith acknowledges his generosity in the support of a collection of national antiquities:

As keeper of our National Antiquities, Mr Franks cannot be surpassed in the knowledge requisite; and I may add, in generosity; for like General Pitt Rivers, he cheerfully allows his purse to be taxed when the Government objects to purchase (Smith 1891, 184; see also 185–86).

The British Museum, in return, benefited immensely from Smith's undertakings; his collection formed the basis of the Museum's collection of national antiquities (Smith 1857, appendix; Kidd 1977; Potter 1997, 130–32; MacGregor 1998, 134–37; Polm 2016, 212–13).

Smith's volumes attracted subscriptions from 121 institutions, including major national institutions such as the British Library, the Museum of Science and Art (South Kensington) (Table 16); university libraries (e.g. Cambridge University); major regional libraries (e.g. Corporation of Liverpool, Corporation of Manchester, Dorset County Museum and Library, Leicester Permanent Library); free libraries (e.g. Cambridge); and book societies (e.g. Sandwich Book Society). A number of subscribers played a key role in establishing and reforming universities during this period, including the politician James Heywood (Ward 1965, vi), who supported women's suffrage and the opening of London degrees to women, and worked with Thomas Wright, Henry Hallam (Clark 1982), who helped to found the University of London, and William Cavendish (Earl of Burlington) (The Times, Tue. 22 Dec. 1891; Issue 33514), a leading philanthropist and the first chancellor of the University. Free and public libraries flourished during this period, and collections expanded rapidly. James Heywood was a keen supporter of the free public library movement, founding and maintaining the free library in Notting Hill.

Smith's personal connections were critical: for example, Daniel Wilson was a notable anthropologist and university administrator (Trigger 1992; Ash and Hulse 1999) who moved from Edinburgh to take up a chair at the University of Toronto; hence the University of Toronto Library subscription. That Smith's work was valued internationally is clear from subscribers such as the Berlin Royal Library; the Academy of Sciences, Arts and Belles Lettres of Caen; and Melbourne Public Library, New South Wales: these subscriptions further enhanced his status as an internationally-recognised expert. Other subscribers associated with libraries include Richard Thomson (Smith 1883, 130) 'the accomplished Librarian of the London Institution'; Joshua Stratton, sub-librarian at Canterbury Cathedral; Beriah Botfield (Botfield 1849); Philip Bliss, sub-librarian at the Bodleian under Bulkeley Bandinel; Henry Christmas, librarian of Sion College, London and Charles Lovell who helped to develop the Guildhall Library. Joseph Mayer founded the Free Library at Bebington (Cheshire). The role that librarians played in the selection, classification and dissemination of archaeological knowledge, particularly through personal connections, merits further investigation.

| Volume | Price | Number of subscribers | Source | Total subscriptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coll Ant 1 | 24s | 94 | £112 16s | |

| Coll Ant 2 | 24s | 133 | £159 12s | |

| Coll Ant 3 | 24s | 201 | Note in Preface to Coll Ant 3 | £241 4s |

| Coll Ant 4 | 24s | 213 | £255 12s | |

| Coll Ant 5 | 24s | 207 | £248 8s | |

| Coll Ant 6 | 24s | 201 | Notice, Coll Ant 5, 364 | £241 4s |

| Coll Ant 7 | 30s | 148 | UoL flyer | £222 |

| Catalogue | 15s | 342 | UoL flyer | £256 10s |

| Illustrations | 63s | 344 | English Catalogue | £1,083 12s |

| Richborough | 21s | 296 | English Catalogue and UoL flyer | £310 16s |

| Pevensey | See list of subscribers for individual contributions | 76 | Preface | £76 14s |

| TOTAL | 2,255 | £3,208 8s |

The approximate total value of the subscriptions listed here, bearing in mind the limitations of the sources (Scott 2013b), is £3,208 (not including multiple subscriptions or large formats or additional sales and contributions) (see for e.g. The Reliquary, 1872-3, 14, 53 for prices for unsubscribed copies) (Table 20). An average middle-class annual income was around £150 during this period (see Wages and the Cost of Living in the Victorian Era), while a vicar might earn as little as £40 to £50 (see Measuring Worth). This is therefore an impressive achievement, given the challenges that Smith faced. As many of his subscribers were from middle-class backgrounds, their financial investment in his projects was considerable, suggesting serious commitment to his causes and/or the importance of being seen to commit to these.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.