Cite this as: Duffy, P.R.J. and Popple, S. 2017 Pararchive and Island Stories: collaborative co-design and community digital heritage on the Isle of Bute, Internet Archaeology 46. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.46.4

Heritage is widely recognised as a major asset for communities, both for improving social identity and driving economic change (e.g. Cultural Heritage Counts for Europe 2015; Heritage Lottery Fund 2015). Local groups are frequently encouraged to adopt new digital methods as a means of promoting, marketing and consolidating cultural assets in a spirit of often boundless digital optimism (Popple 2015). These digital engagements are often underpinned by an a priori set of assumptions about authority, skills, confidence, digital access and framed by an 'uncritical' enthusiasm for new technologies (see Bonacchi and Moshenska 2015 for further exploration of the current landscape). In many respects the quest for new digital methods and resources can seduce practitioners and communities alike, but their novelty and seeming appropriateness can conflict with conditions on the ground (in terms of access and sustainability), competencies (in terms of training and digital literacies) and sensibilities (in terms of traditions and practices).

In recognition of these issues, we want to discuss the practices and experiences of a group of community and volunteer archaeologists on the Isle of Bute through our experience of two recent research projects (Figure 1). In the first, the Pararchive project (2014-15) the team worked with islanders to co-produce and develop community-appropriate digital tools for research and storytelling, to create what eventually became the YARN platform.

The second project, Island Stories examined in detail some of the issues identified through early work on the Pararchive project. This six-month project, conducted between July and December 2014, sought to consider the different characteristics and traditions of this specific community and their approach to the 'digital', and what might be enabled through the then imminent arrival of improved broadband services to address important cultural, economic and demographic issues facing their community.

Our article explores our experiences working with the community groups on these projects, and examines how the process of co-production contributed to understanding specific needs and potentialities in a challenging and changing digital heritage landscape. The experiences of participants, processes of collaborative co-design, engagement, upskilling and the empowerment of citizens are discussed, and reflections on the experience and effectiveness of co-production methods and what it meant for islanders are explored.

The Isle of Bute is a small island situated in the Firth of Clyde. It is fifteen miles long and four miles wide (24 by 6.5km). Nearly all of the island's (c. 6500) residents live on its east coast, with the majority concentrated in the central main town of Rothesay and smaller coastal settlements. The remainder are scattered throughout the rural hinterland on farms and in former farm buildings.

In the second half of the 20th century economic changes, particularly a collapse in tourist numbers and an increasingly technologised agricultural economy, had a significant impact on the island community. Between 1951 and 1971, the resident population of Bute reduced by around 35% and, by 2011, it was estimated that Bute had only around 50% of the 1951 population. Despite best efforts, the historical absence of an effective strategy for island sustainability has had a corresponding negative impact, with social deprivation and local employment statistics highlighting the poor performance of the Bute economy compared to both regional and national averages (Ekos 2010; Highlands and Islands Enterprise (HIE) 2014).

Ambitions to reinvigorate the local economy have recently become more clearly focused (e.g. Argyll and Bute Economic Forum 2016), and are often intimately related to the need for better physical and digital connectivity (see Popple et al. 2015 for wider discussion). Heritage is also frequently identified as a critical part of the regeneration mix, but despite a central place in several national historical narratives (e.g. a power centre in the 6th-century Southern Dalriadic kingdom; a key ecclesiastical centre in early Christian monastic expansion; a royal power base of the Stuart kings in the 14th and 15th centuries), the wider heritage persona of the island remains dominated by its role as a seaside tourist mecca of the 19th and early 20th centuries (see Duffy 2012a; 2012b).

This limited outward expression of island heritage is, however, in contrast to a vibrant history of local exploration of archaeology, which stretches back to the mid-19th century. Much early engagement focused around local society activities but, more recently, nationally linked initiatives such as the Scotland's Rural Past Project, and the £2.8 million multi-partner Heritage Lottery Funded Discover Bute Landscape Partnership Scheme (DBLPS) promoted a widening of public heritage activism beyond the social bounds of the traditional local society model (Figure 2; see also Thomas 2014).

The result has been enhanced local community skills and, critically, a more clearly expressed role for local residents as knowledgeable activists and collaborators in archaeological explorations on the island (e.g. Moshenska 2008). This role became apparent in the early work of the DBLPS project, where a symbiotic knowledge exchange between staff of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland and local people resulted in a radically enhanced local SMR (see Geddes and Hale 2011), and reached its fullest expression through the co-design approach employed in developing An Archaeological Research Framework for Bute, which offered equal weight to both enthusiast and paid practitioner community interests in a series of workshops and consultations to create a research framework that reflected both (see Duffy 2012b).

At the time of the invitation to join the Pararchive project in 2014, several things were therefore clear. Local enthusiasm for egalitarian heritage development was substantial and had benefited from sustained efforts to invigorate further a core tradition of local community involvement in heritage through the DBLPS project. Furthermore, recent work through the DBLPS had reinvigorated understanding of the island's past and offered a rich well from which to draw information and inspiration to inform wider audiences. How and if this potential might be further developed through new digital platforms to support not only a local sense of self, but also emerging economic regeneration themes, was one of the key interests of the project learning ambitions.

In 2014 the University of Leeds invited the heritage community on Bute to become partners on the Pararchive project and to participate in the co-production of community-designed digital heritage tools. The project comprised community partners (active heritage groups in Bute, Stoke-on-Trent and Manchester), academic partners (University of Leeds, University of York), institutional partners (the BBC and the Science Museum Group) and private sector partners (Carbon Imagineering) and was intended to produce a new open platform to allow users to harvest and orchestrate existing online archival sources and share their own as a means of enabling community research, encouraging collaborative practice, participation and the sharing of knowledge and experiences (Popple and Mutibwa 2016).

Unlike existing platforms in 2014, it was envisaged this would allow users to organise and link materials across all online sources and act as a single access point based on the integration of public archives with intuitive storytelling tools. It was specifically designed to exist as a de-institutionalised space to foster connectivity across and between communities and cultural institutions and a free workspace for a range of heritage, creative and research projects (Adair et al. 2011; Popple 2013).

As a wider learning ambition the project looked to address crucial issues related to the idea of open digital space, and the free use of cultural assets, self-owned heritage collections and the potential to build new online communities. The project wanted to address what we felt were some of the key barriers to participation, especially in terms of ownership of materials, insights and knowledge. Foremost were community concerns about the appropriation of content by third-party organisations and fear about copyright infringements and the loss of ownership of heritage items such as family photographs and personal ephemera. To prevent this and protect the intellectual property of our community partners we decided to adopt the strategy of hosting links rather than embedding digital content and allow users to host their digital assets on platforms of their choice, such as YouTube, Instagram or Vimeo. We were particularly keen to hear about their own practices and use of digital tools, so that the platform we produced could be easily accessed and instil trust.

In this respect we felt that the Pararchive project would, through an open and co-produced approach, enable the creation of tools that could easily be adopted as they were co-designed by their users and not imposed from above. In our conversations, and through the work our developers did with the Island groups, we developed a specification that we saw as a potential means of managing the rapidly changing digital heritage landscape and hoped that its collaborative design could help build capacity through reflecting on the potential for developing expertise, confidence and autonomy within its user communities. This original project was an eighteen-month study (2014-2015), which set out to challenge and explore digital engagement assumptions through the collaborative co-production of a new open source web-based digital storytelling, archival and creative workspace platform. Funded by the AHRC's Connected Communities and Digital Futures schemes, the project comprised community, academic, institutional and private sector partners (Prescott 2015; Papadimitriou et al. 2016; see also Connected Communities Festival 2014: Introduction to Pararchive).

To achieve this, we designed a mixed approach to developing the resources that combined strategies developed on the AHRC Connected Communities scheme, which drew on established action research methods, co-production models and evolved what we termed a series of 'Community Technology Labs' to facilitate the specification and design processes (Light and Millen 2014; Facer and Enright 2016).

In short we wanted to provide resources for communities that would allow them to achieve the following:

From a local community viewpoint, participation in the development of YARN and its use within Island Stories offered a number of attractions. Key among these was the opportunity to build on the recent upskilling of local volunteer enthusiasts by widening the appreciation of web-based technology, and thus enhancing wider public appreciation of new local research and resources through the digital environment as a new outlet for local heritage stories.

As well as the potential to discover new web-based ways of telling Bute's stories, the concept of community co-design as the mechanism for doing so addressed an issue that had been encountered several times in previous local work. Group experience of web interfaces had sometimes been one of frustration, as participants with basic digital literacy struggled with a 'top-down' (Thomas 2014) imposition of embedded web concepts into projects that were often outside their frame of reference. The opportunity to co-create a web interface that took account of community skills and abilities was therefore both timely and appealing.

Crucially, the bottom-up process proposed in the co-design methodology also allowed participants to maintain control of both definitions of subject matter and curation of content (Simpson 2010; Sayer 2015). This is, of course, not an entirely new approach and much groundwork has already been laid through the development of history from below methodologies, peoples' history projects and pioneering co-production work fostered through the history workshop movement (Thompson 1966 and Samuel 1981). Central to our concerns, and drawn from such democratic precursors, were the transformative power of what has been characterised as, 'a need to cut through the rhetoric of custodianship' (Smith and Waterton 2009, 11).

This democratised approach to local explorations of archaeology and heritage, previously encouraged locally through the DBLPS project, was promoted through an entirely supported but hands-off approach. At the same time, third-party hosting of privately curated material such as postcards, photographs and other memorabilia and historical ephemera provided reassurance to owners regarding the fate of their personal collections, which had sometimes been gathered together over decades of collecting practice or formed part of intimate family archives.

Critical to the process of content development was the project structure and design. Although the digital page was presented as a blank sheet and subject matter was entirely defined by the individual participants and/or groups of participants, content development was carefully nurtured through a series of technology and design workshops. This can perhaps best be envisaged as an ecosystem of mediated information exchanges, with local groups firmly at the centre of the network (Figure 3).

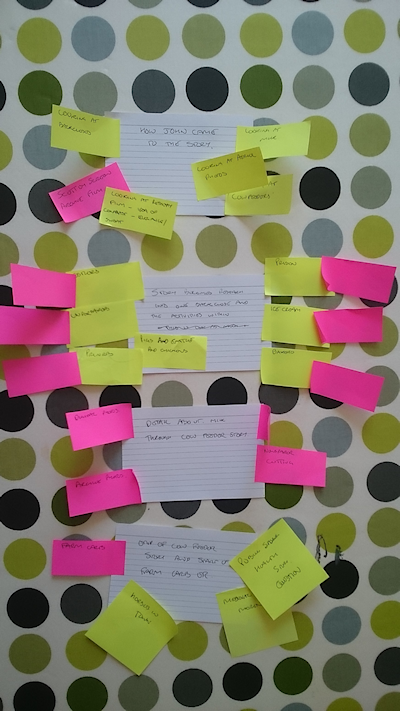

A key example of how this worked can be seen through the exploration of the history of milk production on the island, which began with a field survey of an abandoned farm. From initial field records, a building biography was disentangled from the physical ruins as a series of kernels (Chatman 1978) called 'passages' by the project design team. A series of related 'items' (photographs, maps, drawings, online film etc.) were then identified that could help tell that story (Figure 4). Observation of the series of round-table conversations through which this was achieved formed the basis of the design of the digital architecture of the web platform, which was fed back to the group, firstly as a paper design and then as a series of increasingly more sophisticated digital iterations. This design process of listening, reflecting and questioning that emerged became one of 'deep hanging out', a concept affectionately appropriated by the design team from the work of Clifford Geertz (1998).

At the same time, group discussions relating specific modifications and additions at the farm to wider events such as the creation of the Milk Marketing Board or accession to the common market group provoked questions to institutional partners as to the presence and availability of curated material held in their archives in order to illustrate the YARN story better. Identification of this material (the National Science Museum Group for example hold a substantial Milk Marketing Board archive) in turn triggered conversations and actions that explored how potential barriers such as historic copyright could be overcome to achieve institutional ambitions of better public accessibility to (and usability of) archive material. Learning about this process was captured across all levels by the project research team.

Reflections on the Bute community responses to the project were enlightening when considering the benefits and limitations of collaborative practice in the co-design of the YARN tool. In terms of design, community participants were clear that the tool successfully captured their needs and requests for digital storytelling: functionalities such as the ability to interlink elements of heritage stories, for example, were key identifications made by local communities when considering how they told and shared stories around a table. Several participants also became particularly interested in the process of deconstruction of storytelling methods and their subsequent digital reconstruction.

The project also had a significant and measurable impact in terms of upskilling, promoting a greater confidence in the digital environment and enabling new experiences and practice. One local participant, for example, subsequently embarked on digitisation of his own private collection of memorabilia relating to Bute comprising several thousand items, while others benefited from an enhanced knowledge about the relationship between copyright and the digital environment, leading to a more informed consideration of choices when presented with opportunities to contribute to digital archives through other projects such as the Imperial War Museum's 'Lives of the First World War'.

The project also allowed groups to remotely connect with each other across the UK and recognise their successes and frustrations in understanding their past. Integral to the knowledge sharing that emerged was an appreciation that the challenges the Bute group faced in approaches to their heritage were shared by other groups, including academic, institutional and private sector project partners. This wider appreciation served both as a reassurance that methodologies for actions such as data archive could be problematic for everybody, and as an incentive to keep going.

A number of interesting challenges also emerged during the project. The initial call for participants resulted in 15 people attending the first two introductory meetings, but 18 months later only 5 people remained to complete the project. A certain amount of this volunteer dropout was anticipated — people were asked to contribute free time to attend monthly meetings as well as undertake ongoing archaeological survey work and for several people this proved too much to accommodate. At least three people, however, reported that participating in the process of archaeological survey was enough — when offered the opportunity to develop their data and observations into a more substantive story, people simply declined. Some of this attitude may in part result from a hesitancy to engage with the digital environment (see below) but it must also be acknowledged that for some the familiar components of fieldwork practice (camaraderie, team working, outside activity etc.) are an end in themselves, with less concern over what subsequently happens to the data and information that are generated.

In total, six aspects of local heritage were explored during the Pararchive project, creating a series of 'classical' narratives or stories (Chatman 1978; Herman 2009). Three became digital 'Yarns': the contextualisation of a building biography, a short exploration of milk production on Bute, and a story about an archaeological artefact. Of the remainder, an exploration of women in farming was never fully realised in any output form due to the participant moving off island and leaving the group both physically and digitally, while participants who created stories based around a 17th-century Court of Session record of a 'witch' trial, and the history of a local tile and brick works chose to disseminate their stories through local society lectures, and traditional journal-based papers, despite an active engagement in the digital design process over a number of months. While the co-designed digital architecture of YARN also offers the opportunity to experiment with what Chatman (1978) calls 'anti-stories', nonlinear journeys in which multiple story choices are possible through links, this was not a choice taken by Bute participants.

Intrigued by the questions that these observations posed, the team gained a small grant to pursue a short follow-on project 'Island Stories' from the UKRC Sustainable Societies + programme. Island Stories used mixed methods — interview, research, invitations to participate in digital mapping, paper and online questionnaire — to assess key structural and contextual barriers to digital connectivity and the associated impacts on cultural and economic activities. Our key ambition was to assess the potential for a major project of research and training to develop an integrated and community-owned response to improved digital access and help islanders fully utilise community expertise in the development of Bute's heritage economy.

The key findings from the Island Stories project also clarified and restated some of what we understood about local attitudes to heritage and the digital environment. People were found to be informed and engaged as a result of previous and ongoing heritage initiatives, with about two-thirds of people reporting direct engagement with heritage places and activities as opposed to the one-third of the Scottish population reported in the contemporary Scottish Household Survey (Scottish Government 2013). A pro-active and energetic approach to heritage on the island was identified, marked by pride and local expertise and supported by key local organisations (in particular Brandanii Archaeology and Heritage, Bute Museum, Mount Stuart Archives, and smaller genealogical and nostalgia sites). Digital familiarity was also relatively consistently reported, with little evidence of the digital divide reported from the responders. However, although people were found to be ambitious for heritage to become a key component in improving island fortunes and were highly motivated to participate, a lack of 'island heritage' identity and cohesion was also clear, with a lack of coordination inhibiting the development of an integrated island heritage offering.

Processes of collaborative co-design offer multi-faceted opportunities for engagement, upskilling and empowerment of individual participants. Clearly much was learned by everyone who took part in the Pararchive project, with measurable development of digital skills, increased confidence in the digital environment and, for some, an intellectual reimagining of the meaning of traditionally recognised roles of 'expert' and 'public'. One clear success for Pararchive in this latter advance was the democratised ecosystem created by project partners, in which university academic became island story collector, retired heritage enthusiast became digital designer, archivist became archaeologist, and institutions became individualised, and much of the reason for this lies with the enthusiasm, skillsets and balance of the project participants across all sectors.

However, as our experiences through both the Pararchive and Island Stories partnerships have also taught us, it is equally important to recognise that at a community user level it is individual participants who dictate how engaged, upskilled or empowered they wish to become within that process. Critical in our learning was the recognition that while the carefully considered co-design process clearly achieved the production of web-based tools designed around the demands of community users, and those community users were demonstrably proud to have helped create YARN, this did not in itself automatically generate a reflexive desire to utilise the tools in a rush towards individual heritage storytelling.

It was also clear that while the opportunity to utilise digital tools for heritage storytelling was welcomed by some of the local community members on Bute, others remained less convinced, choosing instead traditional venues for sharing (or possibly imparting) knowledge. Some were willing fieldwork participants, but unenthusiastic interpreters, preferring to leave their raw data in the hands of others to do with as they wished. Others embraced the same camaraderie in the design process that they enjoy in archaeological field practice, but were reluctant to stand out-with the collective when asked to develop work on their own. In short, while both Pararchive and Island Stories demonstrated a clear enthusiasm for the democratisation of knowledge collection processes and for digital co-design, the presentation of a tool to enable an enhanced digital democratisation of the traditional processes of knowledge dissemination provoked more mixed reactions.

These outcomes raised interesting questions around the process of co-design and the digital environment for the Pararchive team. Was a preference for paper outputs simply the effects of the often identified 'digital divide'? Did people actually want to take advantage of the opportunity for democratised participation, or did they just enjoy being part of the process to create something that would help make it happen? Had we also made more fundamental assumptions that digital would naturally equal democracy for participants when in fact utilising traditional hierarchical venues of knowledge dissemination (see Richardson 2014 for a wider review) offered them better expression of acquired empowerment?

The findings of Island Stories perhaps offered something of an explanation: that while the concept of democratised self-generated digital heritage was strongly supported across the community, the imagining of the place of empowered self in this new model, and the recognition that familiar hierarchy-dominated narratives need not apply were less clearly understood. In short, the transition from an understanding that heritage knowledge is received from 'experts' to a recognition that self-generated digital storytelling offers an alternative in which everyone can participate was a deeper process that our initial 18-month project had been able to facilitate.

One of the key consequences of these findings and our experiences of co-production is the recognition we need to develop digital skills and offer key resources in a longer-term partnership. In order to do so, a new project beginning in 2017 will build on the learning achieved to date utilising the YARN platform and local newspaper archive, held in Rothesay Library. Working with staff at Rothesay Library, Argyll and Bute Council Local Studies Department stories and adverts will be identified from the newspaper archive that illustrate how the future was articulated and imagined in the past under the broad theme of 'Exploring Past Futures'.

In developing this project, a different approach will be taken in presenting invitations to participants, focusing more on encouraging a more varied demographic spread. By presenting YARN as a fully functioning platform we will also examine the process of co-design from a different viewpoint: will the knowledge that the YARN platform has been designed through a 'bottom-up' approach be valued by a new set of participants, or is digital functionality the primary desire for users? We are also interested in how people react to working with the archive of a familiar local newspaper that was identified in the Island Stories project as a key contemporary information vehicle, and whether one key to pushing 'heritage to action' (Waterton et al. 2017) may be presentation of non-academic sources as a 'way-in' for exploring heritage stories. Finally, the project will examine our hypothesis that central to achieving a truly democratised digital heritage landscape is long-term collaborative commitment between communities and institutions, and time.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.