Cite this as: Ljungar-Chapelon, M. 2017 Virtual Bodies in Ritual Procession — Digital co-production for actors and interpreters of the past, Internet Archaeology 46. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.46.6

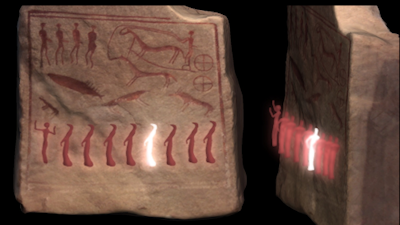

The main challenge of this digital co-production process consisted of adapting an artistic interpretative idea concerning a Bronze Age procession depicted on one of the stone slabs of the Kivik Grave into the context of a Rock Carvings exhibition (Figure 1). This interdisciplinary experiment was based on the key idea of integrating the museum visitor as a participant into the interpretative process of this ritual procession through 'natural interaction', i.e. a mode of gesture-based interaction where museum visitors only interact thanks to the movements of their bodies and do not need to use traditional game interfaces such as a joystick, game controller or other devices. On the one hand, the museum visitor is able to participate in an artistic experience and to become part of a 'free and open' interpretative process, but, on the other hand, the topic at the core of this experience is an archaeological finding. For this reason, the creative process was, to some extent, contained within archaeological boundaries, so that the presentation of the stone slab's ritual would not be incompatible with the archaeologists' interpretation. The greatest challenge was to develop a digital, artistic and hermeneutical experience that would not misrepresent the results achieved through archaeological research, while opening up the interpretative process, clarifying what remained unknown to archaeologists and stimulating the audience's imagination.

In a previous article (Ljungar-Chapelon 2017), I described in detail the specific archaeological and artistic research context and the ideas behind the construction of this interactive experience for museum visitors. This article illuminates another side of the prism, focusing on the digital co-production process itself, and discussing how this worked towards including museum visitors as actors/participants in digital co-production through body gestures and their hermeneutical questioning.

This interactive experience and installation was called Virtual Reality Arts Play referring to the philosopher Gadamer's concept of play (Spiel in German; also game and drama) in Truth and Method (Gadamer 2004) and to my thesis, Actor-Spectator in a Virtual Reality Arts Play (Ljungar-Chapelon 2008, 13,100-103). In that thesis, I define a VR arts play as a type of experience where several art forms can be interwoven and in which a spectator/player is given the opportunity to become physically part of a virtual reality-based artwork and performance by interacting with the virtual environment. Departing from the original meaning of play as 'dance', Gadamer gives metaphorical examples such as 'the play of light, the play of the waves', and explains play as a 'to and fro movement, not tied to any goal that would bring it to an end' (2004, 102). According to the philosopher, the 'play' mode of being consists of this movement, backward and forward, between the spectator/player, the artistic content and its creator (Gadamer 2004, 103). Therefore, 'the work of art is not an object that stands over against a subject for itself…', it is, instead, that ongoing movement that constitutes the work of art itself (Gadamer 2004, 103). In this VR arts play, the art forms were dance, 3D-art and music performed with Bronze Age instruments in the intimate setting of a rather small room. The performance started with a 3D-model of the stone slab being projected on the wall in front of the user; wondrous rock carving figures would then emerge from the stone, led by a person raising her arms in an adoring posture (Figure 2). At that point, bronze lurs would begin to sound, and the red, robed figures would start moving forward with smooth body gestures; they would escape the grave, suddenly reappearing in a dreamy sunbathed South Scandinavian landscape, to then melt again into the stone and the silence of the grave.

The virtual reality-based application was programmed with the Unity3D system and used Microsoft Kinect to track and connect users' movements to the white figure in the procession. The user could then experiment with body gestures that differed from those of the robed figures, try to mimic the movements of the others in order to melt into the procession, becoming red, or just enjoy the experience in the way she found fit (see video-film).

Before being available to public audiences, this digital co-production process was tested by members of the production team (Figures 3-4). We will thus examine this pilot phase, before analysing audiences' responses.

Following Gadamer's definition of a work of art as the result of play (see above), co-production seemed the most appropriate design methodology for the development of art experiences. In this particular case, the VR arts play was created through to-and-fro movement between:

The creative production process began with an experimental phase resulting in the launch of a prototype. This work was undertaken collaboratively by an interdisciplinary team from Lund University and, more specifically, from the Department of Design Sciences (also called Ingvar Kamprad Design Centre or IKDC) at the Faculty of Engineering, and from the Lund Humanities Laboratory and the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History at the Faculty of Humanities. The researchers, engineers and students involved worked in the fields of digital technology, digital artistic representation and archaeology. This first phase consisted of motion-capture experiments following a trial and error method that allowed us to explore different paths and scenarios unconditionally. It resulted in several presentations in academic and cultural heritage contexts, including the conference Multidisciplinary XI Nordic-Tag–Kalmar 2011 and an open research seminar about archaeology and digital heritage held by the interdisciplinary research group Digital Heritage Forum (Lund University 2011). Short video sequences showing virtual bodies in movement were presented on these occasions, and one of them featured moving figures inspired by the cist-slab procession of the Kivik Grave. The initial feedback from the academic and museum worlds was positive and, at the Lund seminar, representatives from the 'Österlens Museum', the culture historical museum of the city of Simrishamn, expressed an interest in engaging in a process of digital co-production, and sought a collaborative partnership with the faculty of engineering within the framework of their forthcoming rock-carving exhibition.

The idea of developing an innovative prototype for interactive user-experiences that would then be further developed for use in an exhibition context was then proposed to a group of fourth-year students from the faculty of Engineering as a possible project, as part of the 'Virtual Reality in Theory and Practice' module. The first draft of the storyboard, developed by the artistic researcher, was handed to them and discussed; thereafter the prototyping phase began with several tutoring and production meetings where the chosen digital solutions were reviewed and improved, while the narrative was adjusted accordingly. In this conceptual prototyping phase, the key question of how to use body interaction in order to open up the interpretation process to the users was thoroughly addressed. The underlying theoretical core of the discussion dealt with how to artistically and practically generate the to-and-fro movement of play between the museum visitor and the digital, archaeo-artistic material. The ultimate solution that was identified was that of triggering a strong identification process so that the museum visitor could feel as if she was melting into the procession when imitating the gestures of the virtual figures. At the same time, we wanted to open the interpretative process and give the museum visitor the opportunity to distinguish herself from those wondrous figures by imagining and performing body gestures that would convey her own interpretation of the cist-slab's figures. Choosing from several options, it was decided to underline the user's interpretation by means of a change of colours, so that if a user chose to perform radically different movements from those of the red procession figures, the virtual figure selected would change to white. During the prototyping phase the team also discussed the social side of a VR experience and particularly whether it would be technically possible to have more than one user performing at the same time, since a former VR arts play had shown that sharing an intimate VR experience had a positive effect on the user's experience, if the users involved enjoyed each other's company (Ljungar-Chapelon 2008, 150).

Along the way, technical, time and financial constraints had to be dealt with — for instance it was impossible for a single motion-capture system to track several users moving together at the same time in the same room, which meant that the virtual procession could only be performed, i.e. gesturally interpreted, by one museum visitor at a time. However, it did prove possible for a smaller group of people standing in the same room to have a closer look at the performance. Thus, even though only one user at a time could participate in the procession, other people could simultaneously witness and reflect on the performance. As a result, an interaction between spectators/witnesses and the user, all engaged in the to-and-fro movement of play within a collective interpretative co-production process, was made possible. Experimental testing with audiences was first conducted at the Virtual Reality Lab. (IKDC) and, afterwards, at the Museum of Sketches of Lund as part of the annual Conference Innovation in Mind (2013). The prototyping thus involved various audience groups, comprising academics from a number of different disciplines as well as museum visitors and professionals, whose responses could be documented through observations and taken into account for further development.

During the second phase of the production process, academics from Lund University, collaborated with the culture historical museum of Österlen and a tourism and local cultural heritage enterprise in charge of the site of the Kivik Grave, in order to write a joint application to fund the development of the prototype for the planned exhibition of Petroglyphics — Virtual Rock-Carving Experiences (Österlens Museum). Funding from the County Council of Scania was secured and used to recruit an interaction designer, artistic 3D-modellers and a music producer to join the production team. The co-production phase with the museum began with a meeting to decide where the virtual procession could be placed within the exhibition space, and the appearance of the room that had to be specially built for it in terms of dimensions, inner design, projection surface, Kinect-system's positioning, entry and exit alternatives, taking into account technical and artistic requirements as well as users' preferences and needs. Subsequently, an iterative process started where the story board and interaction design were progressively improved along with adjustments concerning the 3D rendering of the landscape and the procession figures. These were modified so that their movements could mirror the user's body movements and harmonised with the sound-landscape, in order to optimise the visitor experience. In this second phase, the team tested artistic ideas to effectively integrate visual and musical content with the archaeological knowledge. Given the exhibition context where the application would be used, artistic ideas that museum archaeologists considered to be at odds with archaeological information were left aside (e.g. the early idea of procession figures performing their ritual by dancing around a big oak tree bathed in sunrays).

All in all, reflecting over such a digital production process, and the various challenges encountered by the production team, two aspects revealed themselves as particularly crucial in order to overcome mental, time, financial and geographic barriers: (1) the ability to communicate with each other through shared cognitive maps and (2) time flexibility.

The production process as interdisciplinary collaborative work between Lund University and the Museum of Österlen went on harmoniously, facilitated by the fact that the researchers and experts involved within the Department of Design Sciences, the Humanities Laboratory and the Institution for Archaeology and Ancient History were already collaborating in interdisciplinary projects, through a digital heritage network. Open-mindedness and the effort to understand one another's perspectives beyond individual working-fields were the prerequisite of a fruitful collaboration. Not surprisingly, the main difficulties we encountered in undertaking digital co-production were the limited financial resources and the time constraints. Limited funding proved insufficient to cover all of the staff costs, despite the first prototyping phase being completed as an undergraduate course-project and therefore free of charge. Another challenge, partly linked to the two described above, was the physical distance between the partners, since the media firm in charge of the interaction design was not located in Lund where the Virtual Reality laboratory and the core of the production team were based. This complicated the iterative process, which depended on tightly collaborative team work between artistic researcher, interaction designer, virtual reality experts, music producer and museum experts and archaeologists.

The timing of the production process was decided based on the storyboard and needed to be simultaneously carefully planned and flexible. The digital and artistic content was tested and produced separately in smaller specialised groups, with the plan of combining it at the end. The basic thread of the storyboard was known from the beginning by all members of the production team, but the storyboard underwent continuous updating in order to adjust to the digital solutions and ideas developed by the groups, who were constantly informing each other of their progress. The artistic researcher who participated in all the smaller groups was mainly in charge of timing and internal communication, whereas the final phases of the project demanded an especially tight collaboration between members of the 3D-modelling and interaction design teams. Due to the physical distance, in person production meetings with the interaction designer were limited in number, and communications about this important aspect were digitally enabled. This was not ideal, since interdisciplinary collaboration where not all team members share the same technical vocabulary is better undertaken when there is the possibility of meeting face to face, sharing ideas and, for example, commenting on visualisation options in real time by testing small alternative adjustments with a trial and error method. Nevertheless, working in close proximity towards the end allowed us to overcome these difficulties and complete the application, which was tested in situ at the museum of Österlen, and presented to journalists before the opening ceremony of the museum exhibition.

The essence of digital co-production in this experimental research project can be described as a creative process, engaging first and foremost professionals from different institutional contexts — a government and a community institution — and private enterprise in collaborative and interdisciplinary work undertaken by sharing cognitive maps.

Petroglyfiskt — Processionen (Filmversionen) from Digital Heritage Forum on Vimeo.

This VR arts play was considered a work of art and science that could not be complete without the participation of the audience. It was mainly intended as one person's intimate experience that could be experienced by other museum visitors following and watching the performer. In her dissertation, Canadian contemporary painter and VR artist Char Davies, who has created intimate virtual reality-based experiences, states that immersive virtual space can be used as a medium for transforming perception (Davies 2003; 2005). In one of her famous installations, called Osmose (1995) the navigation was directly linked to the body of the user and activated through that most vital function of the human body, breathing in and out. In a similar way, addressing the audience as participants, but creating mesmerising pieces of large-scale art that can include many persons simultaneously, the Danish artist Olafur Eliasson is nowadays one of the leading artists creating monumental works that immerse the audience in an experience of art. One of them was The Weather Project (2003), with its sun rising at the Tate Modern in London, UK. In an article in Time Magazine entitled Meet your Maker Richard Lacayo (2007) explains that Eliasson's work is about what happens when the viewer is looking at the piece of art and that his pieces cannot exist without a viewer interacting with them. In this sense Eliasson's pieces are thought as co-productions between the artist's work and the viewer and it is probably not a coincidence that as a former breakdance artist, the artist managed to inspire viewers to participate with their whole bodies in the sun-rising experience. This can be observed in some photographs of The Weather Project, where museum visitors spontaneously seem to have 'choreographed' sun or star motifs, interacting within the installation by mirroring the sun while lying together on the floor (see pictures 2 and 4 at the artist's website).

Returning now to the VR arts play, following a similar line to Davies and Eliasson, my desire as an artistic leader and researcher was to engage in co-production with museum visitors, appealing to their bodies and body movements to imagine and try to interpret and, together, in the present day, revive a ritual depicted on a stone slab that archaeologists found to have had a strong connection to the sun and Bronze Age cosmology (Kaul 1998; Goldhahn 2013). In that sense, it was a matter of bridging a time-gap between now and then by reviving existential human questioning about the power of the sun, something as vital for humans and artists today as it was for people from the Bronze-Age.

Several methods were used in order to collect and analyse the reactions of the museum visitors. Along with an audience survey (Ljungar-Chapelon 2015) — with an unexpected high response rate of 96%, in which museum visitors wrote personal comments — observations, group discussions with children and in-depth interviews with archaeologists and museum experts were conducted. A total of over 250 people participated in the audience study. This study focused particularly on the VR arts play as artistic, archaeological and digital experiment, but also included other parts of the rock-carving exhibition with other types of archaeological and interactive experiences. These included 'digital treasures' accessible via IPads; a larger interactive touchscreen called FlatFrog with many layers of information, including photographs of archaeological finds and places, texts and stories; and a virtual slab on which users could paint their own rock carvings with interactive pens.

One of the most important results of the audience research is that 94% of the museum visitors, adults as well as children, thought that new technology combined with art that engages the viewer's body enables the construction of new forms of knowledge and audience experiences. Furthermore, observations of the VR arts play enabled the collection of spontaneous statements and thoughts expressed by visitors at the exhibition. One example is that of the variety of ideas the audience had regarding the nature and iconography of the ambiguous creatures, both human and animal-like, depicted on the cist-slab. Children variously identified them as penguins, moose, snakes and seals. Once they had made up their mind, most children kept believing their specific interpretation, and this impacted on their experience as a whole.

In order to know how the VR arts play was perceived, the following question was included in the survey:

How would you rate the following alternatives on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1 means uninteresting and 5 means very interesting. Please circle one number per line

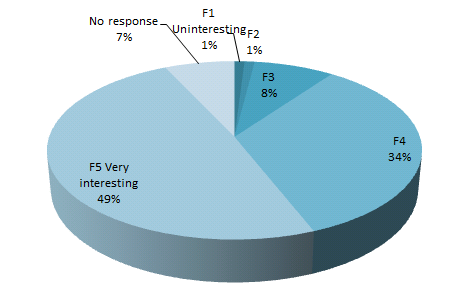

Respondents rated 'visual representation, music/sound and movements as a whole' very positively, as shown in Figure 5.

The VR arts play was appreciated as an interesting and/or very interesting experience by over 80 per cent of the audience, whereas only one per cent thought it was uninteresting.

Detailed responses concerning individual sensory components highlight the superadditive character of this multisensory experience. That means that the addition of the various stimuli (visual, auditory, kinetic) was more important than the sum of the respective stimuli (Ljungar-Chapelon 2017). Beyond these three stimuli, some audience referred to 'room and picture melting together'; this kind of comment points towards something even bolder that I would call real/virtual space stimuli and that could be described as the interweaving between virtual space and real space stimuli. This interweaving results from the endeavour of an artistic leader to immerse the museum visitor as actor/participant in a staged setting, through virtual space stimuli within a 'real' exhibition room. In the VR arts play, intersensoriality achieved through full-body interaction in a mixed environment of real and virtual space worked towards enhancing the experience as a whole.

At an individual level, by physically engaging themselves in an interactive sensory experience, museum visitors interpreted the virtual procession in contrast to or as part of their life here and now. Even if it was a virtual experience with virtual rock-art figures projected on the wall and not a procession, performed live by flesh-and-blood actors, the large majority of the audience viewed themselves as participants in the procession and not merely as spectators/observers of moving figures. The VR arts play was to be directly experienced by one museum visitor at a time, and was first and foremost experienced and interpreted as a personal and intimate experience when visitors entered the installation room alone.

The experience became collective when a group of visitors (family members, friends, school pupils, visitors and professionals on a guided tour) entered the room together and looked at each other performing. In school groups, the presence of other pupils in the room while one was performing by dancing in front of the others proved, as expected, to have a strong influence on the experience of the group as a whole. Depending on pupils' age and gender and on the group dynamics in a specific class, the social context could at times have either an inhibiting or a stimulating effect. Generally speaking, performing with body gestures in front of others was easier for 9-10 year old children than for teenagers. Some of the latter expressed their desire to be left alone, without other classmates looking at them, while other pupils (mostly boys) reacted in the opposite way, finding it enjoyable to perform in front of others. No matter the age of the museum visitors, sharing an experience with others had in all groups an impact on interpretative processes (see Figures 6 and 7).

The combination of physical and cognitive-emotional involvement through 'body and soul' stimulated pleasure, interest, thoughts in line with the way in which the virtual procession was represented in the VR arts play or critical alternative interpretations expressed both orally or through written comments. Although some disagreed, the majority of the audience considered the gestural interpretation as a truthful representation and proposal of the way the procession might have been performed during the Bronze Age. This shows that the interpretative process was not 'locked up' but open, and triggered different responses. Furthermore, audience responses could be analysed using the notion of emotional intelligence developed by psychologists or neurologists like Antonio Damasio (1999) and bridging the gap between emotion/feelings and rational/logical abilities (see also Ljungar-Chapelon 2017).

Trying to identify intertwined physical and cognitive-emotional components of the experience as they emerged from the written and spoken comments of the audience in order to list them as separate aspects might seem a bit artificial and contradictory. However, it can be fruitful in order to gain a better understanding of the interpretative process of this particular VR arts play and of digital co-production as a whole. The principal facets of the cognitive-emotional involvement as expressed by the audience were:

Below are examples of museum visitors' comments; these quotes show the entangled cognitive-emotional aspects listed above, and how all of them combined contribute to a general feeling of participation (adult response denoted by (a)).

| Intellectual, emotional |

|---|

| It's more fun and you get more interested of it [archaeological finds and rock carvings]. Goodby! :-)[with smiley] Thank you for inviting us! (girl, 13 year) |

| More Empathy, more curious, more motivation, better understanding and remembering (a) |

| Learning, understanding, remembering is easier (a) |

| One understands at a deeper level, it stimulates the imagination. Gave me a completely new perspective about the motif [the cist slab's rock carving's motif of the procession] that I earlier experienced as pretty frightening (rituals, Ku Klux Klan, human sacrifice) (a) |

| As a spectator you become more involved in the exhibition and will more easily remember what you saw and learned. One becomes part of it and use several senses (a) |

| Gives experiences, feelings and thoughts (a) |

| Feeling of participating (a) |

| Gives new dimensions (a) |

| Physical, emotional, intellectual |

| I thought this was much more fun than usual… Somehow I do not like the other [exhibitions] without technic, it just uses to be someone talking and one listens. It is more fun when you can do things here as long as you have an explanatory notice. (boy, 9 years). |

| Because then you can participate a bit more and you become a little like a part of the exhibition. It is also good to get to try to do what they did in the past. (girl, 11 years) |

| Because you can do things here instead of standing still (boy, 9 years) |

| One is in the middle of the action, it feels as if you are really there. It helps people understand how it might have been (a) |

| Experiences with body and senses gives knowledge that stay in another way (a) Felt as one was part of it (a) |

| I did not reflect about who I represented when I moved, I just did it, I was just here and now (a) |

| Physical, social, ritual |

| Meditative spiritual dance (a) |

| Music and movements under praising and worshiping (a) |

| Dance ritual (a) |

| Dance in group (a) |

| Dance and yoga-movements(a) |

| Dance and group influence. Taking part in an Aerobic-session, dance in ring movements (a) |

| Spiritual, social, nature related |

| Solemn, ceremonial, evocative (a) |

| Mysteriously belonging (a) |

| Lone and Belonging (a) |

| Importance of social procedures to go ahead after mourning (a) |

| Our own burial ceremonies (a) |

| Requires more involvement, increases the feeling of presence (a) |

| One in a team. (woman) |

| Being in communion with the universe(a) |

| Nature worship, sat in a trance (a) |

| Majestic procession on her way to something important (a) |

| Mindfullness. (woman) |

| Highspirited, devoted (a) |

| Fervour (a) |

| Mystic (a) |

| Historical, emotional |

| It was like coming back to the roots of time (a) |

| An experience of suddenly becoming part of history (a) |

| A trip back in time (a) |

| Attempts to participate in, get in contact with this time (a) |

In summary, the study allowed us to establish the strong impact of an interactive artistic intersensory experience that engages the whole body to help museum visitors construct a wide range of interpretations from archaeological artefacts and findings. As we have seen earlier, physical participation in an artistic experience taking place in a real/virtual space generated the cognitive-emotional involvement of the audience, and nurtured connections with spiritual, social, historical, ritual and religious aspects of the ceremony as it might have been performed and its meaning in our time. Even though new technology was an indispensable condition to achieve this, the digital component of the experience did not require any digital skills on the part of the user. Users did not need to actively and consciously deal with digital tools, since the VR arts play was based on natural interaction.

To make the interpretative process transparent for the audience was one of the main challenges in this project. When interviewed (28 October 2014) about the VR arts play and asked to draw on her professional experience as Malmö museum's exhibition chief, Josefine Floberg reflected on the concept of truth. According to Floberg, transparency should be a main concern when planning a historical exhibition, since the majority of museum visitors tend to have a positivistic preconception of the concept of truth. On the one hand, they have high expectations about the representations and experiences proposed by the museum and a natural tendency to interpret them as truthful mirrors of the reality of past times. On the other hand, that cannot always be the case, considering that archaeological interpretations are based on incomplete and often ambiguous archaeological findings. At the same time, Floberg underlined that an exhibition manager should dare to interpret with sufficient degrees of freedom and collaborate with artists in order to produce sensory experiences that can open new dimensions and perspectives for the audience. Hence, honesty and transparency are necessary, especially to mark the distinction between more or less certain artistic representations. The fact that, despite thorough explanations by a museum educator, one child experienced the VR arts play as 'what [people] did in the past' shows the difficulty of being pedagogical. A strong engagement through body gestures and other senses might indeed boost identification with the past alongside a belief in a supposed 'truth'. This can be seen as something problematic, although I would argue that, from a hermeneutical perspective, it might be legitimate to engage the audience through play as long as the latest archaeological research is taken into account. One could say that the limits imposed by the ambiguity and lack of information concerning the Bronze Age imagery of the cist-slab allowed at the same time the possibility of involving the audience in a chorus of voices nurturing a multi-faceted collective interpretative process. Following Gadamer's conception of truth as regards to a work of art, and the urge for transparency as expressed above by Floberg, I will assert here that, in relation to the VR arts play seen as a work of both art and science, what this chorus of voices expresses is revelations as truths, providing an opening for existential reflections concerning central aspects of human life bridging the time-gap between now and then.

When an interdisciplinary experimental and physical approach combining archaeology, digital technology and art of the kind described in this article succeeds in involving the audience as actor/participant and interpreter of the past, it has the potential to generate a deep connection with specific archaeological findings and the human past and its history, more generally. This research project is an example of a kind of digital co-production characterised by users' physical performances as interpretative acts facilitated by digital means, and taking place in a specific environment where virtual and real space, illusion and reality melt together. As previously mentioned, this archaeo-artistic and full-body experiment triggered strong cognitive-emotional involvement, with the audience mostly acting as both participant in and interpreter of the past. From a hermeneutical point of view, the creation and analysis of this chorus of voices help to broaden interpretative processes, and to reach beyond the disciplinary boundaries of archaeology. This process allows a personal appropriation of material culture by museum visitors having different backgrounds, understanding and knowledge. Thus, I believe that this approach, appealing to emotional intelligence, represents a contribution to a democratic process towards a greater level of interest in, knowledge of and identification with a common cultural heritage by a diverse public.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.