The Day of Archaeology was a volunteer-led public international archaeological blogging event that ran from 2011 to 2017. The event took place on a single day of the year, always in June or July, although in practice posts were submitted and published throughout the week either side of the day itself. The project asked people who define themselves as archaeologists to submit one or more blog posts about their working day. Images and video were also submitted, and there was associated discussion both in comments on the website as well as on dedicated pages on Facebook, and using the hashtag #dayofarch on Twitter.

Participation was free and there was an open call for contributions, although contributors were required to register in order to participate, and all the posts were subject to moderation by the editorial team. During the lifetime of the project, 1934 contributor accounts were created (although 46% of these did not post a contribution), and a total of 2379 posts were published.

This article explores the history of the Day of Archaeology and the practicalities of running a large-scale, collaborative blogging project, before examining some of the topics covered in the posts. An assessment of the impact of the project follows. Overall, through this article we hope to answer some of the basic questions arising from this form of collaborative, online, global engagement – what we did, who we reached, what people talked about – and also to provide some insights for any other similar initiatives that may follow us in the future.

The Day of Archaeology was first conceived in a Twitter conversation between two erstwhile archaeology PhD students (ML and LR) during the Day in the Life of the Digital Humanities, a community wiki project organised by the University of Alberta in March 2011. In this, digital humanists across the world write about one day in their working lives (Day in the Life of Digital Humanities 2011). We realised that the varied nature of archaeological work meant that the discipline was supremely suitable for a similar project. In a matter of minutes, a small core of digital archaeologists (JAD, SE, TG, JO and DP) was recruited via Twitter, along with an offer of free hosting on the UK-based Portable Antiquities Scheme's servers.

The organic evolution of the project resulted in no explicit aims or goals in the first instance. It was only through reflection on the successes and failures of early years that the team began a discussion in earnest on the scope and potential of the day. In 2013, in a message circulated among the organisers, JAD expressed the aims of the project as follows:

Aim 3 arose partly in response to the Day of Archaeology event held in Garfield Park, Washington, DC, which took place on the first Day of Archaeology in 2011 (Archaeology in the Community 2011).

The project was not driven by commercial interests – it was free to join, free to read, and managed by a collective of dedicated volunteers committed to creating an archaeological community in the most cooperative, accessible, and equitable way possible. The 'behind-the-scenes' and unscripted approach to the project offered information about archaeology both as a practice and as a discourse, as well as all the discovery, excitement and mystery that is now the bread and butter of archaeological media. For many participants this was their first foray into the use of blogs for digital public engagement, and the Day of Archaeology demonstrated the benefits of 'doing' public archaeology in its digital form to a new audience within the discipline.

Explore archived posts in ADS by category

Buildings

Commercial Archaeology

Community Archaeology

Conservation

Digital Archaeology

Education

Environmental Archaeology

Excavation

Historial Archaeology

Museum Archaeology

Public Archaeology

From 2015, the project began to work in co-operation with the NEARCH (New ways of Engaging audience, Activating social relations and Renewing practices in Cultural Heritage) project, managed by the French Institut National de Recherches Archéologiques Préventives (INRAP), through their UK project partners Archaeology Data Service (ADS) (NEARCH 2015). This collaboration provided financial support from the NEARCH project for archiving the Day of Archaeology website and its associated social media, and for the preparation of the present publication. Working with NEARCH also provided access to multilingual editors, and widened the approach to the project beyond the Anglophone archaeological community. The NEARCH project partners across Europe acted as moderators, and supported the dissemination of the Day of Archaeology posts via their own institutional networks.

The collective made the decision to retire the Day of Archaeology project after the event in 2017, as this also coincided with the end of institutional support from NEARCH, and an offer of archiving with the ADS. In addition to these pragmatic changes, there was a sense that interest in the project was declining, both in terms of numbers of posts uploaded by archaeologists, and a decline in the numbers of visits to the website.

The site was built using the WordPress Content Management System (CMS). WordPress was chosen because it offers simple customisation, and was felt to be a relatively easy way for contributors to create posts, embed media and links, and respond to comments.

Detailed instructions on how to use the WordPress system were made available before the day, and support was available on the day itself to enable archaeologists who were not familiar with the system to contribute. Site search was powered by Solr. Hosting was initially provided by the Portable Antiquities Scheme.

Since 2012, the Archaeology Data Service (ADS) have hosted the Wordpress site, and have taken responsibility for ensuring the long-term accessibility of the posts (see digital archive) in the event that the WordPress platform becomes unavailable or the current format of embedded video ceases to be readable (Jeffrey 2012).

Many of the decisions made by the core organising team were on an ad hoc basis, often responding to feedback from the previous year or through active engagement with community contributors via social media. Nonetheless, some standards for sign-ups, submissions, moderation, and licensing were followed throughout. We will touch briefly on some of the key aspects of these practices before moving to the demographics of our contributors and visitors.

Decisions about management were made collectively, initially via the services Basecamp and Writeboard, although after 2016 discussions were primarily via email. During the lifetime of the project the organisers held just one physical meeting, at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London, following the UCL Archaeology & Communication Research Network (ACRN) workshop on 16 May 2011. This was because of a combination of the expense of travel and the time commitment required, as well as the increasing geographical distance between organisers as the project progressed.

In addition to the authors of this article, at various times Pat Hadley (UK), Jaime Almansa Sánchez (Spain), Monty Dobson (USA), Alice Gorman (Australia) and John Lowe (USA) were members of the organising group. From 2016, with the involvement of the NEARCH project, additional moderators were recruited from partner organisations in France (1), Germany (1), Greece (1), Italy (3), The Netherlands (1), Poland (2), Spain (1), and United Kingdom (3).

As part of a commitment to collaboration and crowd participation, an open competition was held to design a logo for the project in May 2011. Submissions were made via flickr. The winning entry (Figure 1) was designed and submitted by Glenn Hustler. The logo was subsequently edited for each following year.

Rather than allowing direct registration of users on the website, contributors were asked to send an email. Login details were then issued by the project team. This additional administrative involvement was designed to avoid the creation of spam accounts sometimes associated with online platforms, but also to establish from the beginning a degree of human contact between contributors and the members of the organising team.

Most contributions were made directly via the WordPress interface. Instructions on how to use WordPress were made available on the website. A decision was made to allow submissions via email in order to encourage participation by those archaeologists who may be reluctant to sign up or create their own posts. As well as being posted on the website, posts were shared via the dedicated Twitter account and on the project's Facebook page.

Content was made available under a Creative Commons Attribution Share Alike licence (CC-BY-SA 4.0) unless contributors wished to maintain copyright, in which case exceptions could be made.

Our goal from the beginning was to keep editorial control of content to a minimum, allowing the members of the archaeological community to express their own ideas, in their own voices, as much as possible. To avoid potentially harmful content or language, however, the Day of Archaeology also instituted an acceptable use policy. This stated:

'A Day of Archaeology is moderated by volunteers. Submissions will not be accepted that are irrelevant, defamatory, obscene, abusive, threatening, or an invasion of privacy. Derogatory remarks or innuendo towards any individual or group, including those that may be construed as offensive by any individual of a certain race, gender, sexual orientation, or religion, are not acceptable. The decisions of the moderators are final' (Day of Archaeology Organisers 2017).

Real-time moderation of posts was adopted as the best means of making sure all content adhered to these basic guidelines. In early years, the moderators worked closely together throughout the day to check posts for formatting and any inappropriate content. From 2014, following the implementation of a new theme for the site by JAD and JO and given the growing international scope of the project, the moderation workflow was codified more formally. Instructions for moderators included assigning a featured image, formatting the appearance of the post on the site's homepage, setting a location and series of categories for the content, and checking for any problems with formatting or hyperlinks. Additional steps were required for formatting video content or image galleries. In order to avoid overwhelming concentrations of posts appearing online simultaneously, moderators also scheduled posts to appear at regular intervals throughout the day, as far as possible given the different time zones of the moderating team in a given year.

The growing potential of the site as a resource for archaeological pedagogy and engagement also encouraged the reflective reassessment of our moderating practices. In the early years, for example, posts were moderated but not consistently tagged with topic-based categories or geographic regions. A lack of options for easy exploration by topic became an increasing hindrance to site navigation as the number of posts grew. The use of the project by students enrolled in the Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) Archaeology's Dirty Little Secrets, offered by Brown University on the Coursera platform and in which JAD was involved as a course designer (for more about this course, see Alcock et al. 2016), in particular, provided substantial feedback on how potential visitors were encountering online materials. This feedback made it abundantly clear that user-based discovery was structured primarily via categories and tags, and so assigning both became part of the moderation workflow. Similar adjustments to the posting and moderating guidelines, based on both formal and informal assessment, continued to shape the project throughout its duration.

From the outset, the project was advertised by the organisers via their social networks, and through relevant online mailing lists. Announcements were made in the UK magazine British Archaeology, as well as in SALON, the newsletter of the Society of Antiquaries. From 2016, NEARCH partner institutions posted announcements about the project to their professional networks. Dissemination was largely limited to venues relevant to archaeology; however, some non-archaeologists with large follower bases amplified the project to their social media networks, such as The Guardian journalist Maev Kennedy, and the American musician Neko Case (Figure 2)

“@m_law Archaeologists around the world are blogging about their working day today http://t.co/Nq84pZIXAC @trowelblazers !

— Neko Case (@NekoCase) July 26, 2013

Academic presentations about the project were made by LR at the Oxford Experience in 2013 (Richardson 2013), by ML at the Society for Historical Archaeology conference in Leicester, UK, in 2013 (Law et al. 2013), and by JO at the Computer Applications in Archaeology conference in Paris, France, in 2014 (Day of Archaeology Organisers 2013). The project formed a case study within LR's doctoral thesis (Richardson 2014a), and was the subject of a publication in Post-Classical Archaeologies (Richardson 2014b). In July 2014, the Italian website Professione Archaeologo carried an interview with ML about the project (Law 2014). In 2012, the project was shortlisted for the category 'Best Representation of Archaeology in the Media' in the British Archaeological Awards (it lost to the TV show Time Team, then in its final season).

Funding was a source of discussion at several points in the project. Ideas involved crowdfunding, producing a book containing material from the project and, in 2012–13, incorporating as a co-operative or Community Interest Company. All of these ideas eventually stalled, largely owing to a lack of capacity on the part of any of the volunteer organisers to make the requisite time commitment for a substantial fundraising push. From 2014 an online store was established at zazzle.com, managed by AR, which enabled buyers to put the Day of Archaeology logo on a variety of products. In 2015, NEARCH took over the funding of the domain name and this was the point at which the hosting was transferred to ADS.

Aside from the hosting, which had previously been provided by PAS until 2015 (along with DP's time for the duration of the project), support in kind came from two UK-based commercial archaeology companies. L–P: Archaeology provided time for JAD, SE and JO to contribute, and Wessex Archaeology provided time for TG to contribute.

There are a total of 2379 posts on dayofarchaeology.com. The total number of posts per year is presented in Table 1.

| Year | Number of posts |

|---|---|

| 2011 | 427 |

| 2012 | 350 |

| 2013 | 358 |

| 2014 | 406 |

| 2015 | 304 |

| 2016 | 268 |

| 2017 | 266 |

There are 1934 user accounts registered on the site. Of these 885 (45.8%) did not contribute a post, and 402 (20.8%) contributed more than one post. The most prolific account, associated with the former Royal Commission for Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (now Historic Environment Scotland), posted 70 contributions between 2011 and 2016. The number of new registrations per year is presented in Table 2.

| Year | New registrations |

|---|---|

| 2011 | 448 |

| 2012 | 358 |

| 2013 | 264 |

| 2014 | 443 |

| 2015 | 141 |

| 2016 | 134 |

| 2017 | 146 |

Site access statistics were recorded using Google Analytics. Figure 3 presents the number of sessions per day between March 2011 and May 2018. The individual Day of Archaeology events are associated with clear peaks in visitor numbers; the most popular, with 6849 sessions, was in 2014. It is clear that engagement with the site was consistently focused around the date of the event itself, with little ongoing engagement. Table 3 shows the number of sessions on each year's Day of Archaeology. Throughout the period since March 2011, the mean number of sessions per day is 188.9 (standard deviation 115.1; skewness 1.9), while the median is 190.

| Day of Archaeology | Number of sessions |

|---|---|

| 2011 | 4138 |

| 2012 | 4596 |

| 2013 | 5818 |

| 2014 | 6849 |

| 2015 | 6155 |

| 2016 | 5397 |

| 2017 | 4404 |

Analysis of site statistics reveals that the overwhelming majority of visits (c. 70%) come from Anglophone countries. Of 582,366 sessions, 182,851 (31.4%) were from the United Kingdom and 158,117 (27.15%) from the United States. The involvement of Jaime Almansa Sánchez, and later the NEARCH project, enabled a greater number of non-English language posts. The top 20 countries of origin of sessions are shown in Table 4. In total, however, visits have come from over 150 countries globally.

| Country | Number of sessions |

|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 182,851 |

| United States | 158,117 |

| Canada | 28,726 |

| Australia | 20,932 |

| Italy | 15,616 |

| France | 13,574 |

| Germany | 12,909 |

| Spain | 12,155 |

| Ireland | 10,297 |

| India | 9,583 |

| Poland | 7,078 |

| Netherlands | 6,430 |

| Greece | 5,454 |

| Russia | 5,451 |

| New Zealand | 3,854 |

| Turkey | 3,799 |

| Brazil | 3,526 |

| Sweden | 3,435 |

| Macedonia (FYROM) | 3,402 |

The majority of visits result from discovery via search engines. Of the 582,366 sessions since March 2011, 294,431 (50.6%) have originated from search engines. Most of these are from Google, although around 3% come from Bing, and slightly less than 2% from Yahoo.

In terms of social media, the largest driver of traffic to the site is Facebook. Since March 2011, 70,373 (67.2%) of the 104,667 sessions referred from a social network came from Facebook, in comparison to 25,943 (24.8%) from Twitter. This prevalence on Facebook is slightly surprising, given the origins of the project within the Twittersphere, the active Twitter profiles of many of the key organisers, and also the relatively little time spent by the project team in specifically targeting Facebook engagement.

Explore archived posts in ADS by period

Prehistory

Mesolithic

Neolithic

Bronze Age

Iron Age

Roman

Romano-British

Anglo-Saxon

Viking

Early Medieval

Medieval

Post-medieval

As well as a reflection of the working days of individual archaeologists, the corpus of posts spanning the seven years represents a palimpsest of both archaeological practice and the wider social, political and economic context throughout much of the 2010s. Shawn Graham carried out data mining of the corpus of posts from 2012 (Graham 2012), while Ben Marwick carried out distance reading of the corpus from 2012 and 2013 (Marwick 2014). As part of the current summary, some elementary text mining was carried out on the entire corpus by ML with the aim of identifying major topics of discussion and trends through time (see https://github.com/drmattlaw/dayofarchaeology).

The content of posts from each year was downloaded from the WordPress admin area of the site in .xml format. This was then cleaned in Notepad++ using regular expressions and the find and replace function to remove code and URLs (Table 5)

| Regular expression | Function |

|---|---|

| <[^>]+> | Removes html code within angle brackets |

| \[[^]]+\] | Removes WordPress markup within square brackets |

| http[s]?\:\/\/.[a-zA-Z0-9\.\/\_?=%&#\-\+!]+ | Removes URLs |

Excess whitespace was also stripped in Notepad++. Text mining of the edited text was carried out using the tm package in R (Feinerer 2017). The tm package was used to remove punctuation and stopwords (a set of common English language words). Custom stopwords were also removed through an iterative process, which involved generating a table of the 100 most frequent words and assigning words that are unlikely to be interesting as stopwords, and then repeating the process until the table looked potentially informative (Table 6).

| Day | Archaeology | One |

| Also | Can | Like |

| New | However | Really |

| Often | Jest | Since |

| Good | Lot | First |

| Nie | Much | Different |

| Will | Any | Jul |

| Around | Jun |

The words 'jest' and 'nie' are likely to reflect the presence of Polish language posts, while 'Jul' and 'Jun' reflect the month in which the event fell. Finally, a list of the 100 most frequently occurring words was exported from R as a .csv format file. An example of the R script used can be seen in Figure 4.

#2015

#loads tm package

library("tm")

#chooses file

text <- readLines(file.choose())

#creates document for tm from file

docs <- Corpus(VectorSource(text))

#converts punctuation to spaces

toSpace <- content_transformer(function (x , pattern ) gsub(pattern, " ", x))

docs <- tm_map(docs, toSpace, "/")

docs <- tm_map(docs, toSpace, "@")

docs <- tm_map(docs, toSpace, "\\|")

# converts the text to lower case

docs <- tm_map(docs, content_transformer(tolower))

# Removes numbers

docs <- tm_map(docs, removeNumbers)

# Removes common stopwords

docs <- tm_map(docs, removeWords, stopwords("english"))

# Removes custom stopwords

docs <- tm_map(docs, removeWords, c("day", "archaeology"))

# Removes punctuation

docs <- tm_map(docs, removePunctuation)

# Eliminates white spaces

docs <- tm_map(docs, stripWhitespace)

# Creates Term Document Matrix

dtm <- TermDocumentMatrix(docs)

m <- as.matrix(dtm)

v <- sort(rowSums(m),decreasing=TRUE)

d <- data.frame(word = names(v),freq=v)

#Exports 100 most frequent terms to .csv format file

write.csv(head(d, 100), "2015top100.csv")

Tables of the top 20 terms from each year were drawn up. A number of terms, not limited to terms in the top 100 tables, were subjectively selected for exploration. Total occurrences of these terms each year were determined using the find and replace function in Notepad++.

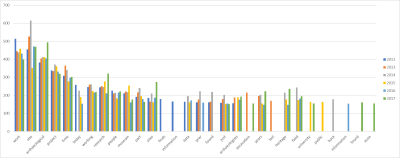

The top 20 most frequent words from each year of the project are presented in Figure 5. These results are largely unsurprising, given the nature of the posts and the Day of Archaeology more broadly. Words like 'site', 'project', 'research' and 'museum' are common each year, although this does suggest that many of the archaeologists contributing to the project have a regular engagement with individual archaeological sites, and with museums. Interestingly, although 'field' is in the top 20 every year from 2014, 'excavation' is only in the top 20 in 2012, 2013 and 2017, and 'finds' only in 2011. Some other words that may be commonly associated with the processes of field archaeology ('sample', 'unit', 'context', 'dig') never made the top 20. Perhaps unexpectedly, for an exercise in public engagement, the word 'public' only makes the top 20 in 2015.

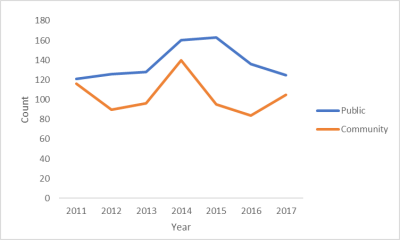

This is not to suggest no mention of the public at all. The subjective investigation of potential words of interest showed little meaningful trend in the occurrence of the words 'public' and 'community' (Figure 6), for example, although both show a sharp increase between 2013 and 2014, although it should be noted that 2014 was also the year with the most posts, which may explain some of the variation.

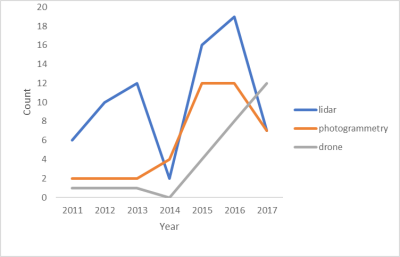

The past decade has seen an increase in the adoption of imaging technologies within archaeology, as costs have fallen and free access provided to government-produced data, such as the LiDAR surveys produced by the UK's Environment Agency (see Haukaas and Hodgetts (2016) for a discussion of the potential of photogrammetry in community archaeology in Arctic Canada). The occurrence of the terms 'LiDAR', 'Photogrammetry' and 'Drone' was investigated to explore whether the technologies are more frequently mentioned through time. This is not the case for 'LiDAR', although 'photogrammetry' shows a sharp increase between 2014 and 2015, maintaining the same level in 2016 before a slight decline in 2017. 'Drone' shows an exponential increase since 2014 (Figure 7), probably a reflection of the wider and more affordable availability of the technology, and a concomitant rise in its use in archaeological projects (for a review, see Campana 2017).

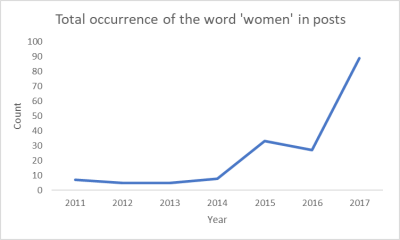

The occurrence of the word 'women' rose sharply after 2014, and entered the top 100 words in 2017 (Figure 8), a likely reflection of the growing visibility of women's issues and inequalities on wider social media, a component of the so-called 'Fourth wave of feminism' (Cochrane 2013). Posts using the word 'women' related to the experience of women archaeologists in the present day, as well as historical women archaeologists and the archaeology and lives of women in the past. Marwick (2014) has previously found that the term 'female' was used almost twice as much as the term 'male' in 2012 and 2013.

The wider political context for archaeology is surprisingly poorly reflected in posts. The United Kingdom's referendum decision to leave the European Union ('Brexit') on 23 June 2016 received 11 mentions in 2016, including a post on the topic by a British archaeologist living and working in Sweden (Wooldridge 2016). A different post looked at the threats posed to – and opportunities presented by – archaeology in a 'post-truth' world, inspired by the Brexit referendum and the nomination of Donald Trump as the Republican Party presidential candidate in the US (Brockman 2016). However, in 2017 the term only appeared in one post (Wooldridge 2017).

The project began at a time of economic recession, and has run through periods of cuts to budgets of state agencies in the UK and, more recently, in the US. A small number of posts have reflected these financial restrictions, as well as pressures relating to archaeology within an institutional context, such as the threat to cease teaching the subject of archaeology at the University of Manchester in 2017 (Chamberlin 2017). The occurrence of the words 'cuts' (references to the 'cuts' in the sense of archaeological stratigraphy or butchery were excluded) and 'recession' are presented in Table 7.

| Year | Cuts | Recession |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 3 | 7 |

| 2012 | 1 | 0 |

| 2013 | 1 | 2 |

| 2014 | 3 | 1 |

| 2015 | 2 | 1 |

| 2016 | 2 | 0 |

| 2017 | 8 | 1 |

Explore archived posts in ADS by country tag

United Kingdom

United States

Italy

Ireland

Australia

Canada

France

Germany

Spain

The Netherlands

The Day of Archaeology project arose organically, and until 2013 did not have a stated set of aims. Had it been a structured project, an evaluation report to funders might highlight the large number of posts and the diversity of participants; the platform given to community archaeology groups; the international nature of the project and the worldwide readership. We have previously claimed that the project 'shows how a large-scale collaborative resource can be set up at minimal expense, using an established and easy-to-learn platform supported by a dedicated email address, Facebook page and Twitter hashtag. As such it could provide a model for smaller scale collaborative online events, possibly in conjunction with offline public engagement activities, for example an open weekend at a national monument or excavation, or a community recording project' (Law et al. 2013). While this is true, we wish to take this opportunity to examine the project more critically in relation to its stated aims: to provide a voice for archaeologists, to increase awareness of archaeology, and to publicise events tied to archaeological projects or sites.

As a platform to provide a voice to archaeologists of all kinds, it allowed professional archaeologists as well as students, community archaeology groups and volunteers within museums and other organisations, a chance to speak about their experiences. However, in keeping with the statement by Richardson (2014a) that 'we must question whether participatory media can fundamentally change, open, or even threaten the authority of archaeological organisations and academic knowledge', we can see that the project was enthusiastically embraced by organisations with traditional authority (see Table 8, showing the most prolific posters). In principle, the project allowed equality of access to the platform for all contributors; in practice this was not equitable as the time made available on the day to public engagement practitioners within established organisations privileged their ability to contribute.

| Rank | Name/Organisation | Sector | Country | Number of posts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland | Government | UK | 70 |

| 2 | Museum of London Archaeology | Commercial | UK | 50 |

| 3 | Philadelphia Archaeological Forum | Non-profit | USA | 48 (combined total of two accounts) |

| 4 | Colchester Archaeological Research Team | Local Government/Community | USA | 35 |

| 5 | Philippa Pearce (The British Museum) | Museum | UK | 28 (combined total of three accounts) |

| 6 | James Dixon | Independent | UK | 26 |

| 7= | Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust | Commercial | UK | 22 |

| 7= | Institut National de Recherches Archéologiques Préventives | Government | France | 22 |

| 9= | Adam Corsini (Museum of London) | Museum | UK | 18 |

| 9= | Oxford Archaeology | Commercial | UK | 18 |

This overwhelming reliance on the goodwill and free labour both of the majority of contributors and the organisers reinforces the observation of Perry and Beale (2015, 158) that archaeological social web initiatives are an exploitative form of capital creation. It is also likely to have been a hindrance to the wider impact of the project, as development of the project was a competing concern in the lives of the organisers.

As a resource to enhance the visibility of archaeology globally, the project gave exposure to a number of archaeologists and archaeological projects around the world. Its reach was international, drawing at least a handful of visitors from most countries. However, the emphasis, both in terms of contributions and visits to the sites, is on Anglophone countries. This is likely to be the result of the personal and professional networks relied upon by the organisers, and some of the most enthusiastic (institutional?) supporters being based in Anglophone countries.

In addition to its own impact, the Day of Archaeology also provided an online nexus for the development of other projects or events from contributors. To give three examples of this, Philadelphia Archaeological Forum ran their own online Day of Archaeology, sharing posts on their own website as well as on the 'official' Day of Archaeology site (Philadelphia Archaeological Forum 2012). Archaeology in the Community began a physical Day of Archaeology Festival (Archaeology in the Community 2011; 2018), initially run concurrently with the Day of Archaeology, but which later became a fully independent event and which still continues. Adam Corsini, of the Museum of London Archaeological Archive, hosted an exploration of the museum's archives on the Day of Archaeology called #ArchiveLottery, which has since grown to become a feature of the Archive's open days (Corsini 2017). At the time of writing, #ArchiveLottery had just won the 2018 Museums and Heritage Award for Innovation (Museums + Heritage Awards 2018).

The Day of Archaeology website provides a wealth of material for research into archaeological practice and digital archaeology in the 2010s, which this article can only begin to explore. We hope that by presenting some of the background and raw figures associated with the project, we can initiate and contribute to the dialogue. As Perry and Beale (2015, 155) have noted, there is a dearth of longitudinal studies in digital archaeology. It is hoped that the seven-year archive presented by this project will offer further interesting opportunities for research into social networks, communities of practice, and heritage discourse analysis, as well as contemporary media use.

The Day of Archaeology Project team would like to thank NEARCH, especially Holly Wright and Katie Green, and all of the individual contributors who have helped to build the project since 2011.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.