Cite this as: Roland, T. 2018 Making Choices — Making Strategies: National Strategies for Archaeology in Denmark, Internet Archaeology 49. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.49.5

In 2008-09 an international board of specialists carried out an evaluation of the archaeology in Denmark with a special focus on developer-funded investigations. Luckily the board had mainly positive things to note about the Danish system in general and specifically the 27 museums that according to the Danish Museum Act carry out investigations in Denmark.

This is not the place to point out all the aspects mentioned in the evaluation — only to note the recommendation to establish regional and national strategies to support the ongoing prioritisation of archaeological work. The evaluation formed the backdrop to the decision in 2011 to produce a set of National Strategies that should help museums prioritise their daily work and serve as a tool for the general administration of archaeology in Denmark. For this reason some background on the legal framework in Denmark and how Danish archaeology is carried out may be useful.

The present Danish Museum Act has basically worked unchanged since 2001 when the 'polluter pays principle' was introduced. Other changes were also executed in the legal work to prepare for the implementation of the Malta Convention in Denmark — a convention ratified by Denmark in 2005. In spite of these rather comprehensive changes, however, the law retained the old (and very efficient) system for the small group of professionally working regional museums which carry out all archaeological investigations in Denmark (except for some specific research projects hosted by universities). In Denmark, thus, no private archaeological companies exist.

In Denmark, all developers can obtain a free initial evaluation by a museum concerning the archaeological potential of their future projects. This free evaluation primarily involves desk-based studies and other non-intrusive methods but might also include minor trial trenching carried out at the museum's expense. If more extensive trial trenching, geophysics survey or other analyses are needed, these must be paid for by the developer.

Extensive trial trenching can only be carried out if it is included in the investigation budget produced by the museum and approved by the state authorities (i.e. the Agency for Culture and Palaces). The budget is always a maximum budget which means that the developer can never pay more for the investigation than what is set in the budget.

Based on the results of the evaluation, the museum informs the developer about the estimated amount and character of significant archaeology in the project area, and with the knowledge of the expected archaeological 'risks', the developer can then evaluate the economic consequences for the project. Against this background, the developer might re-evaluate the project to avoid excavation (and leave the archaeology in situ) and thereby spare the cost of an archaeological investigation. If the developer does not wish (or if it is not possible) to make changes to leave the archaeology in situ, an excavation must be carried out by the museum — again only after a maximum budget has been approved by the agency.

Danish law requires the developer to pay for all investigation needed in the case of the destruction of the archaeology. It is, however, important to acknowledge that only significant ancient monuments can be investigated at the developer's cost. Unfortunately the term 'significant ancient monuments' is not defined anywhere in the Museum Act — and one might ask if it is at all possible to make a distinction between significant and non-significant monuments? This question brings us back to the National Strategies.

Developer-funded archaeology implies hefty prioritising processes. A lot of (archaeological) decisions are made from the very first desk-based studies through to the trial trenching and final excavation, in order to secure that actual significant archaeology is identified, defined and handled correctly. In Denmark about 100,000 project plans are assessed every year by the museums to identify those with archaeological potential. Of these, about 900 sites are extensively investigated by trial trenching etc. Only about 300 sites are defined as containing significant ancient monuments and undergo extensive excavation.

To reduce the project number to a more focused 900 sites, the museum archaeologists are forced through a lot of decision-making based on selection and prioritising. This also holds true for the agency approving the budgets, which of course mirror the chosen archaeological methods and prioritisation of the investigation. But prioritising on a professional level is only possible on a well-informed and general basis and demands that certain standards are adhered to. Here National Strategies were thought to be a fitting tool.

The idea was to make the system not only fair for the archaeology but also for the developer: if any new site holds information that can help to solve or at least contribute to an understanding of special points of interest in the strategies, the archaeology can without much discussion be described as a 'significant ancient monument'. In the same way, if the qualities are not present on a site, then time, effort and money (sic!) should not be spend investigating it. It all sounds obvious and easy, but of course difficulties arise on sites that fall somewhere in between. Here, the strategies are also a valuable tool for estimation and prioritising, and help to make the argument for funding or not funding an investigation easier and, importantly, more transparent.

A crucial question when dealing with National Strategies is self-evident: what is a National Strategy for the archaeology of a country? The question can surely be answered differently in different contexts and from early on in the process of establishing strategies in Denmark, it was important for the Agency for Culture and Palaces to define the purpose and the future use of the strategies. The strategies needed were identified as being a solution that should:

The aim of the strategies was to do better and more focused archaeology and thereby to secure and qualify the relevance of each investigation and to omit investigating sites expected to produce no new information. The strategies should therefore contain updated overviews focused on gaps in our knowledge and if possible suggest methodology — all kept in a short, simple but academic form mainly meant for the professional 'users' (primarily archaeologists at the museums) but also kept comprehensible and accessible for other stakeholders, not least the developers.

To fulfil the professional aims it was essential that the future strategies should address not only 'all' types of archaeological objects (of course an unattainable commission!) but also specific focal points within every single theme/period, special regional and/or national interests and values, general methods (including the use of natural sciences etc.), questions about documentation, archiving etc. — that is: nothing less than the entire spectrum of field archaeology! From the beginning we knew that these goals were very ambitious and, admittedly, not all fully realistic to carry out. Nonetheless, they served as guidelines for our later work.

In Denmark nothing like national strategies for the archaeology had ever been carried out before. It was therefore without any base or tradition that the work was set off. Published regional and/or national strategies from Norway and Sweden, however, served as an inspiration for the Danish version. During the initial discussions, it was clear that a printed version would make the strategies inflexible and out of date within a few years. Instead we wanted to create a viable document relevant for the future, and designed to be more flexible than a printed edition. A web version was therefore chosen making it possible not only to make overall revisions of the strategies within fixed intervals but also to update these whenever new finds or results made it relevant.

Besides the 'physical' form of the strategies, the actual structure of such a document was also discussed. As the primary aim of the strategies was to prioritise the archaeological fieldwork, ideas of regional or structural (i.e. 'settlements', 'grave finds' etc.) entries to the strategies were proposed, but in the end, a more traditional chronological division of the documents was chosen. Only for the Medieval period did the working group find the archaeological methods and framework too complex to incorporate in a single document. Special strategies for urban and rural sites were therefore also formulated. The decisions taken have not really been questioned since they have turned out to be very applicable — not least because several aspects of the actual chronological period can be combined. Thus the strategies have also served as overall introductions.

One thing was to settle the form and presentation of the strategies — another was how to get them written. The resources for the project were (as always for such initiatives) limited, and it was impossible for the agency to hire in experts to execute the strategies. Luckily the idea of National Strategies was embraced by the museums and universities — the institutions in Denmark that generate the majority of archaeological knowledge — and a panel of experts volunteered as authors on behalf of their institutions. The Archaeological Advisory Board (a board of experts attached to the Agency for Culture and Palaces) also played, and still play, an important part in the development of the strategies. On this basis, focal (or network) groups were established for each sub-strategy, and, though hosted by the Agency for Culture and Palaces, a very large part of the work is now carried out in a fruitful three-way cooperation between the agency and experts from the museums and the universities.

Concept to implementation was a relatively long process. There was a gap of almost three years from the initial meetings in the first focal group until the first draft of the strategy could be presented. Of course, a certain hesitancy of the new and unknown played a part in the process. The main obstacle, however, was the lack of time for the participants. Academic conflicts, and unproductive discussions were pleasantly absent and did not characterise the collaborative work: on the contrary, it seems that participants in all focal groups enjoyed taking part in the work and willingly shared their knowledge to optimise the results of the project.

In the beginning, an attempt was made to make all the sub-strategies equal in structure and content. This, however, turned out not to be the right way to go about it. Each period has its own characteristics and special focal points, which made a strict formal structure of the connected strategy unattractive. Still, a certain degree of common structure was retained and all texts incorporate a general introduction of the period alongside its more specific attributes. For example, in the strategy for 'Medieval Rural Settlements', the lack of knowledge about the settlement boundaries, the manifold and great variety of house types in the Medieval period, the differences between Eastern and Western Denmark, and the relatively poor material culture on the settlement sites are all discussed and methodical proposals for excavating cultural layers are presented — all matters that must be taken into account whenever new Medieval settlement sites appear in the field. Beside the text itself, the authors have also made an effort to add plenty of useful plans, maps and other instructive illustrations that may help the reader to compare with their own material and finds. Finally all strategies contain an updated list of relevant literature.

The first National Strategy was released in 2014 (Rural Medieval Settlements) and others have followed in succession (The Palaeolithic/Mesolithic, The Neolithic, The Bronze Age and Abandoned Medieval Churches — final versions of the strategies about The Early Iron Age, The Late Iron Age/Viking Age, Medieval Urban Settlement, Post Medieval Periods and chapters about maritime archaeology and the use of natural science still remain). However, even at this stage, the conclusion seems clear: The National Strategies have proven to be a very useful tool.

The strategies given the museum archaeologists and the Agency for Culture and Palaces a common and much more qualified reference for their work and clarified the understanding between the two professional sectors. They have provided a better, mutual 'frame of understanding' for carrying out the law-given archaeology. The strategies have also made everyone much more aware of the importance of careful analysis of the quality of new archaeological sites. This has meant a much higher focus on the expected kind and amount of new knowledge that a site may provide (and thereby prevent repetitive archaeology). It has helped to prioritise not only between sites but also on site during excavation.

The existence of an official and clear set of strategies that can be referred to in dialogue with the developer has, in several cases, also made this part of the work easier. The published strategies have been a useful document to refer to when, from the developer or the political side, questions are asked about the importance of a specific site and/or about the administration of archaeology in general. The criteria for defining what is a significant ancient monument has now become much more clear for all stakeholders. A side effect of this has been that more investigations now consist only of an 'extended initial evaluation' (including trial trenching), with less important structures being investigated and registered only more cursorily. This means fewer expensive large-scale excavations, without compromising the quality of the excavations or disregarding significant remains. In this way, the National Strategies have had a positive impact on (1) the quality of the archaeology, (2) the information for the developer and (3) the political focus. All three of these elements are important to develop further, and this has made the strategies worth the effort.

An additional advantage is the enthusiastic involvement from museums and universities has resulted in the set-up of smaller groups of experts based on the focal groups. They can be contacted for assistance by other field archaeologists when dealing with unusual and complicated objects. Though mutual expert assistance between the institutions forms part of the general archaeological tradition in Denmark, it has never been formalised in such a way. The now established expert groups will be an important additional tool to optimise future archaeological (field)work.

The Strategies have been successful and serve their goal but a lot of resources have been spent to reach this point and still not all the strategies have been established. The idea behind choosing the dynamic web document as a publication form was to secure that only the most update and current editions would be available. This, of course, will only be possible with an ongoing, and 'everlasting' revision and continuous assessment of the text — a task that involves several challenges. Economic setbacks and questions about resources are of course obvious and foreseen, and it is therefore more interesting in a few words to discuss how to carry out this update, and by whom?

The original (traditional) idea was to regularly revise the documents every 3-5 years by summoning the focal group to have a critical look at the existing text, add new questions and knowledge, and re-publish. But is this really the best way? Would a user-driven solution, where all the professionals involved — not least the museum archaeologists — are given access to the documents to provide a better result? As mentioned before, the main part of the archaeological work and research is carried out by the museums, and a relatively simple login would make it possible for the museum archaeologists to update the strategies with relevant data almost directly from the field, and to continuously suggest additions and supply new knowledge. This would demand some sort of an editorial board to validate the information — but with the high professional standard of the regional museums, it should not take a big effort to carry out an ongoing quality check of the texts. The discussion continues and as always in such cases with pros and cons. As most effort in the near future will be focused on finalising the unfinished sub-strategies, discussions about a way to secure future relevant and updated strategies will have to be concluded later.

Other future wishes for the strategies are linked with the form itself. Though basically seen as dynamic and easily updated, the documents and the design today are still very traditional — a fact that everyone who checks out the web site can easily recognise (even the fact using the word 'documents' shows this traditional approach!). It would therefore be more aligned to use the web medium in a more optimal way and integrate functions that could challenge the more traditional set-up. This goes not only for better search functions and theme abstracts, but also for the ways to extract information across the single sub-strategies. This would, for instance, support a structural entry that would make it possible to study overall chronological themes like 'settlements', 'grave finds' etc. In these matters, time hopefully works for us.

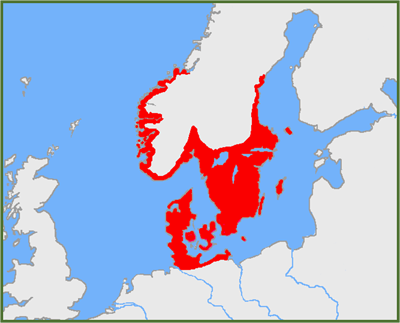

Finally it must be considered whether the strategies necessarily need to be national as the title suggests. For instance, it could be reasoned that a Danish 'national' strategy for the Bronze Age does not make much sense without incorporating material and knowledge from Southern Scandinavia and Northern Germany that made up a cultural unity during this period. Inter-Nordic or other international strategies would require much additional effort and might only be wishful thinking. It is, however, most proper that international cooperation would result in richer strategies that would again raise the level from which we make our priorities and make our choices.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.