Cite this as: Marshall, M. and Seeley, F. 2018 From the Spreadsheet to the Table? Using 'spot-dating' level pottery records from Roman London to explore functional trends among open vessel forms, Internet Archaeology 50. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.50.9

Roman London is one of the most intensively excavated urban sites in the Roman Empire and research and recording of pottery from the city, mostly recovered as part of rescue or developer-funded excavations, has been undertaken on a systematic basis since the 1970s. There has been considerable work on the typology and chronology of vessel forms and their relationship to specific pottery industries (e.g. Marsh and Tyers 1978; Marsh 1978; Green 1980; Symonds and Tomber 1991; Davies et al. 1994; Seeley and Drummond-Murray 2005; Rayner and Seeley 2008) but to date there has been surprisingly little targeted research on the function of specific forms.

This study is an experiment in using data routinely recorded by Roman pottery specialists at MOLA (Museum of London Archaeology) during basic spot-dating/quantification (see below), to consider the function of open vessel forms within and across the groupings used in the London type series (MOLA 2014). Utilising a sample of 45 open forms, represented by 53,459 database records, the potential and limitations of this dataset are explored and trends that may reflect functional distinctions are discussed.

The form of Roman pottery vessels from London is recorded using a type series developed from the 'Southwark typology' created in the 1970s (Marsh and Tyers 1978). Further expansions and alterations made to this original scheme accommodate the discovery and definition of new forms (Symonds 2002; Rayner and Seeley 2008; MOLA 2014). The design is hierarchical, with individual forms assigned to a numbered form group on the basis of their general shape and size, whether they are open or enclosed and whether they have handles (Table 1). Marsh and Tyers' original scheme covered flagons (1), jars (2), beakers (3), bowls (and indistinguishable dish forms) (4), dishes/plates (5) and cups (6). To these have been added: mortaria (7), amphorae (8) and miscellaneous (9) groups. Additional forms, particularly samian forms, have also been added. The numerical form groups are sub-divided into alphabetical form classes of vessels on the basis of typological features such as body and/or rim shape, e.g. 4A bowls with a moulded flange curved sides and flat foot or 4M bowls with a flange below a simple rim, straight sides and a flat base. Some are further sub-divided to reflect finer typological variation e.g. 4A1, 4A2 etc. (Marsh and Tyers 1978, 546; MOLA 2014).

| Type-series form groups | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 Flagons | Enclosed forms with one or two handles and narrow neck |

| 2 Jars | Medium and large enclosed forms, predominantly without handles |

| 3 Beakers | Enclosed forms, smaller than jars, normally with finer surface finishes |

| 4 Bowls | Medium or larger deep open forms (but includes indistinguishable shallower dish variants) |

| 5 Dishes and plates | Medium or large shallow open forms (excludes examples indistinguishable from deeper bowl variants) |

| 6 Cups | Small open forms |

| 7 Mortaria | Open form, often with flanges and spouts, and mostly with gritted interiors |

| 8 Amphorae | Enclosed body with two handles, predominantly large |

| 9 Miscellaneous | including lids, lamps, inkwells. tazze etc |

Each of the London form groups encompasses vessels that share certain morphometric characteristics. These properties may reflect aspects of their intended function and will inevitably have shaped their constraints and affordances (Knappett 2004; Swift 2017) in certain common ways. For example, deeper bowl forms will have been more suitable for containing liquids without spilling them than shallow plate forms, and vessels with small capacities may be appropriate for drinks, condiments or small individual servings, in contrast to large vessels that may have been more suitable for communal serving/dining or cooking (for further idealised examples/principles see for example: Rice 1987, 236–42, table 7.2 and fig. 7.14; Orton et al. 1993, 217–27).

In some instances a fairly well-defined function can be proposed for all vessels within a form group e.g. group 8 (amphorae). Other groups encompass vessels that are inherently more flexible in terms of function, and/or a very diverse range of forms with significant variations in size, rim/body shape and fabric that may reflect, or encourage/permit, differences in use, as seen particularly among the group 4 'bowl' forms discussed in this study (see below). Some of these design features will have aimed to tailor the vessel to a specific function, thus embedding some of the potter's ideas about what the vessel should be used for in its form. However, consumer expectations and other factors such as the potter's level of skill or a desire to be economical in the use of materials or labour also influence the design and the finished product (Pye 1978) and thus function cannot simply be inferred from form. Ethnographic and archaeological studies of vessel function suggest that even quite similar vessels can have different purposes between, or even within, different cultural contexts (e.g. Plog 1980; Miller 1985). Despite this potential for variation, and with a few honourable exceptions (e.g. Hammerson 1988, 247–9; Monteil 2005 and 2012), the potential of London datasets for systematically exploring the function of different vessel forms, either through aspects of their design or evidence for how they were actually used in practice, has largely remained untapped.

Vessel form and fabric, along with basic information about the condition of pottery, such as evidence for sooting or abrasion, are recorded during the initial stage of identification, dating and quantification, of each context pottery assemblage. This stage is called 'spot-dating' at MOLA and these 'spot-date records' represent a basic minimum standard of pottery recording. Our relational database contains more than 440,000 records/'rows' of Roman pottery data of this sort, generated since 1995. Each record represents a unique combination of site code, context, fabric, form and decoration (Symonds 2002). Approaches to quantification have developed over the decades and while weight, sherd count, estimated number of vessels (ENVs), and estimated vessel equivalents (EVEs) are all now recorded as standard, this was not always the case. EVEs in particular were previously recorded only for selected 'fully quantified' assemblages for which more detailed analysis was planned. Similarly, rim diameter information is only available for this more limited subset of the older data but is now recorded as standard.

To maximise the usable dataset here, counts and percentages below refer to the number of database records or 'rows' as this is the only measure that is consistent across all data. This form of quantification is less stable than EVEs and weight but produces comparable results when dealing with larger sample sizes (Symonds and Rauxloh 2003). More detailed exploration and confirmation of patterns would ideally be approached with multiple measures of quantification to reduce potential biases in record counts related to contextual or fabric variation for example (see Davies 1992, 36). However, the high quantity of record-level spot-date data makes it ideal for broad-brush exploratory data analysis of the type undertaken below. Furthermore, for research questions based around function, in which the whole vessel played a part, 'records' have some advantages over quantification by EVEs, typically recorded from rims alone and thus exacerbating state-code recording bias (see below), or weight, which is strongly influenced by vessel size and robustness.

This study examines a dataset, collected and structured as described above, for 45 open vessel forms represented by 53,459 data rows/records from 349 excavation assemblages and attempts to improve understanding of their function, to clarify the potential of 'spot-date' level records for functional analysis, and to determine ways in which our recording methodologies could be improved to support such approaches.

| Morphological category used in this study | Description | Related London form group | London form codes in this study falling within category |

|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | Decorated bowls with simple rims and concave bases with foot rings | 4 | 4D; 4E; 4Dr29; 4Dr30; 4Dr37 |

| B2 | Flanged 'plain' bowls with simple rims and concave bodies with foot rings (or well finished flat feet) | 4 | 4Rt12; 4Cu11; 4Dr36, 4Dr38IMI; 4B |

| B3 | Bowls with simple rims and bodies with curved sides and flat foot or pedestal base | 4 | 4Cam306 |

| B4 | Bowls (and indistinguishable dish variants) with flanged rims and bodies with curved sides and flat feet | 4 | 4A; 4L; 4K |

| B5 | Bowls (and indistinguishable dish variants) with bodies with straight sides and flat bases | 4 | 4H; 4K; 4M; 4Mx; 4Marsh 26 |

| D1 | Larger dishes with omphalos bases and foot rings | 5 | 5Cu31; 5C |

| D2 | Smaller dishes with complex rims and foot rings | 5 | 5Cu15; 5Dr35; 5Dr42 |

| P1 | Shallow plates and dishes with foot rings | 5 | 5A; 5B; 5Dr15/17; 4Dr18; 5Dr18/31; 5Rt1; 5Wa79 |

| P2 | Shallow cylindrical bowl/dish with foot ring | 5 | 5Dr22 |

| P3 | Shallow dishes with simple rims and flat bases | 5 | 5J1/2; 5J3 |

| C1 | Smaller/ more enclosed cups with simple rims | 6 | 6C; 6H; 6Dr24/25; 6Rt8; 6Rt9 |

| C2 | Larger cups or small bowls, generally more open/complex forms | 6 (and 4) | 6A; 6Dr27; 6Dr33; 6Dr42; 6Dr35; 4Marsh35 |

| State code | Description |

|---|---|

| Worn | Wear marks on surfaces probably made as a result of intentional human action |

| Abraded | Loss of surfaces or edge/break abrasion, probably due to post-depositional factors |

| Burnt | Burnt through exposure to heat/fire |

| Sooted | Deposits of soot/carbonised matter on vessel surface |

| Residue | Traces of substances, usually on interior of vessel |

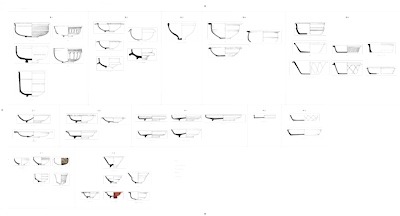

The range of open forms analysed is illustrated in Figure 1. For basic information about data classification and coding of vessel forms used in this study see Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3. Individual forms are described in Table 4. Table 5 presents mean rim diameter and fabric data for each vessel form. Table 6 presents data relating to pottery condition (i.e. 'state codes') using definitions from Table 3.

Tables 4-6. The dataset can also be downloaded as .xlsx

The first number of any specific vessel form code indicates which London form group it belongs to (Table 1). The forms analysed here come from groups 4 (bowls and indistinguishable dishes), 5 (dishes/plates) and 6 (cups). It was felt that formal and functional distinctions between these groups could usefully be explored, particularly to clarify which served as tablewares. Owing to the basic degree of morphological similarity among forms, it was expected that associated data should be fairly comparable.

To facilitate analysis of variation within and across form groups we have also defined intermediate groupings of similar forms called morphological categories (explained in Table 2). The forms are laid out in these categories in Figure 1. Similarly, we place forms into fabric categories based on their prevalent fabric type (see Table 5). These fabric categories are reflected in the colour-coding of form labels in Figure 1.

Forms chosen for inclusion are represented by a minimum of 30 database entries and at least 5 rim measurements. The data for common forms (e.g. bowl form 4H, n=5050) should be very robust while some much rarer forms need to be treated with more caution (e.g. cup form 6C, n=30). In most instances the lowest level of typological sub-division is the form class, e.g. 4A bowls, but 5J dishes have been subdivided into 5J1/2 and 5J3. These have long been recognised as discrete types of vessel (Marsh and Tyers 1978, 566-7) and this is borne out by our analysis below.

Basic details of pottery condition, called 'state codes' at MOLA, are routinely recorded during quantification (Symonds 2002; Table 3 for definitions). State-code recording is simple and designed for speed and ease of use during the study of large assemblages. For each record the presence/absence of the phenomenon represented by each state code, e.g. sooting, is recorded, sometimes supplemented by further description in the database comments field.

These presence/absence data are relatively crude ways of recording complex phenomena but have obvious applicability to the problem of determining vessel function (e.g. Hammerson 1988), as forms that frequently show sooting may well have been used in cooking, and wear may reflect specific behaviours such as the use of utensils. Our results below are generally encouraging, with major differences observed across different forms and some seemingly robust patterns. However, no state code has been recorded for more than 35.5 per cent of the records for any form in this dataset and it must be remembered that these data do not reflect universal functions for idealised forms. Instead they represent an aggregate of the complex biographies of many individual vessels as recorded by pottery specialists.

Variations in state-code evidence within a form could result from multi-functionality, i.e. for a form used both in cooking and on the table some vessels might be sooted and others not. However, it may also reflect inherent differences in the character of vessels, e.g. those produced in softer fabrics may be more easily worn or abraded, or differences in intensity or longevity of use. Some vessels may have been broken/discarded as unused stock (e.g. Richardson 1986, 98) while others may be elderly vessels that have developed wear patterns after years of use.

Other, post-use, factors might include how vessels were washed, potentially removing sooting/residues or causing wear/abrasion (Banducci 2014, 204–5; Croom 2011, 84–8), whether they were broken and discarded while clean or dirty, and how much post-depositional damage vessels have received.

The damage/fragmentation of vessels could potentially have a major skewing effect on the assignment of state codes to specific forms by separating typologically diagnostic elements, such as rims, which are used to classify pottery, from other elements that may exhibit evidence for the vessel's use. Evidence such as wear and sooting is rarely distributed evenly across a vessel (see Cool 2006, 39; Biddulph 2008; Banducci 2014, 192–202) and where this developed on less typologically diagnostic elements, such as bases, it is likely to be systematically under-represented on fragmentary pottery assigned to a form code.

This bias may vary depending on the size/depth of the vessel, how easily different elements break apart, and how diagnostic different elements are. Single sherds from smaller or shallower vessels are more likely to represent a substantial proportion of the profile, incorporating both typologically and functionally diagnostic elements. Large/deep vessels in particular are often identified on the basis of rim sherds alone.

Other systematic biases are possible, such as greater ease in identifying dark burning/sooting on paler oxidised fabrics or in recognising usewear on slipped/colour-coated vessels whose core is a different colour. Such complexities/ambiguities are considered further as appropriate below in relation to patterns observed in the data.

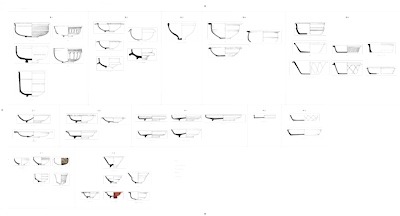

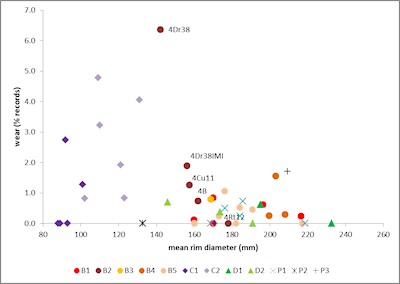

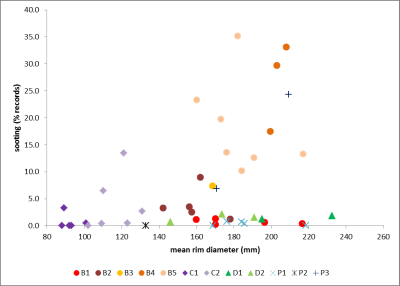

Although the distinctions between Marsh and Tyers' (1978) open form groups were not explicitly articulated in morphometric terms, the range of forms that fall into each indicates that they essentially represent divisions based on size and relative depth. Smaller 'cups' within group 6 are distinguished from the medium and larger vessels within groups 4 and 5 that are described as bowls, dishes or plates as their depth relative to their diameter decreases. Such morphometric differences may relate to function.

The available metric data with which to test, quantify and characterise these group distinctions and consider their functional implications is limited to 3325 rim diameter measurements. These exhibit very significant degrees of variation within forms and there is extensive overlap among both forms and form groups with examples of some group 6 forms, e.g. 6Dr33, reaching 200mm while group 4 and 5 vessels can, very occasionally, be as small as 80mm.This highlights the difficulties associated with assuming an idealised function based on typology/form alone and it is possible that multi-functionality within forms is represented by these metric variations (Monteil 2012).

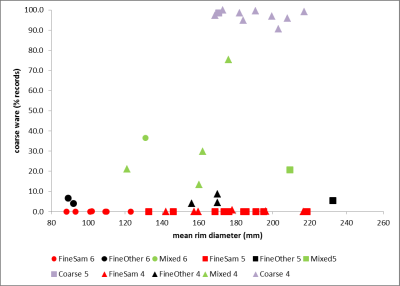

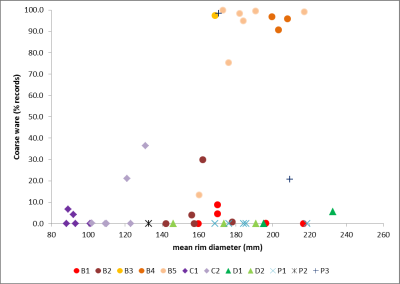

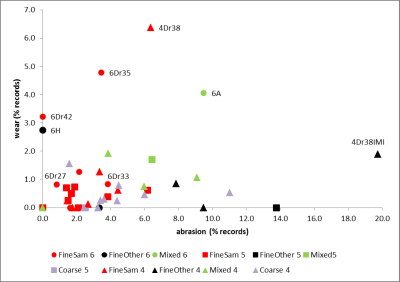

As our metric dataset is limited, the analysis below focuses on mean rim diameters to clarify general trends in sizes across forms. On this basis the distinction of group 6 'cups' from group 4 and 5 forms is relatively well defined (Figure 2). However, one rarer group 4 form, 4Marsh35, has a mean diameter that falls within the group 6 range. This later addition to the type series was imported from another scheme (Marsh 1978, 169-71), where it is described as a flanged bowl and where one or two larger examples are illustrated. However, the form and mean rim diameter of the measured 4Marsh35 vessels discussed here suggests they have much in common with some of the group 6 'cup' forms. Whether this form should be considered a 'cup', in the sense of a drinking vessel, or whether this and some of these other small forms, such as 6Dr35, are in fact 'small bowls' used for serving food is of course debatable. For the sake of metric consistency we discuss our 4Marsh35 data alongside group 6 forms and within morphological category C2 here but, in the longer term, this form needs more careful reconsideration.

Otherwise, group 4 and 5 bowl, dish and plate forms have larger mean rim diameters than group 6 forms but these vary considerably (Figure 2). Depth is an important attribute for the definition of these forms so it is perhaps no surprise that the two groups are not clearly distinguishable from one another in terms of rim diameter alone. In fact coarse-ware vessels represented by some group 4 form codes can vary substantially in depth and encompass deep 'bowl' and shallower 'dish' variants with identical rims (e.g. Marsh and Tyers 1978, 573, fig. 4G.1–3 and 576, fig. 242, form 4H.1–7). As these are indistinguishable on the basis of rim sherds alone and full profiles are rare, Marsh and Tyers (1978, 570) included them all within form group 4. In an attempt to clarify this distinction, 5J dishes, which previously sat within group 4 despite being exclusively shallow, have since been re-classified to sit in group 5 (previously form 4J; Symonds 2002) although our analyses below suggest that at least one variant, form 5J3, may have more in common functionally with members of its original group.

Some shallow dish-like variants of forms remain in group 4, so analysis of assemblages based on an assumed strict morphometric division between London form groups 4 and 5 is problematic. To some degree this problem is insurmountable when dealing with fragmentary vessels. More systematic recording of depth, where possible, might help clarify the degree of morphometric overlap between these groups and the functional implications of differences in terms of capacity for example.

More than 230 individual fabric types are represented within the Museum of London Roman pottery recording system (MOLA 2014). These reflect not just different sources and availability of resources but also conscious elements of design by the potter. For example, at the Northgate kilns different fabrics were being used and these seem to have been preferred for different forms (Seeley and Drummond-Murray 2005). Different clay and temper recipes, surface-finishing techniques etc. could be used to alter characteristics of the vessel such as colour, hardness/toughness or resistance to heat, which may have been regarded as appropriate for particular functions or consumer tastes (Rice 1987, 228–32).

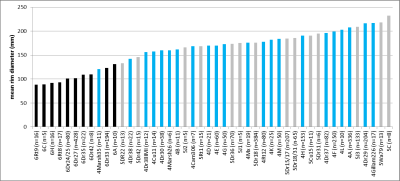

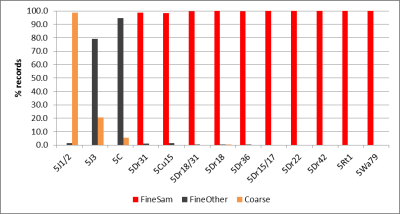

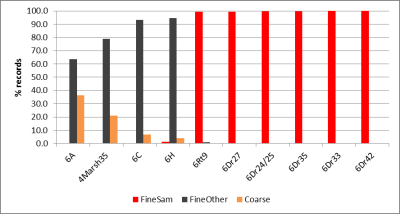

Consideration of individual fabrics has potential to illuminate aspects of pottery function and supply (e.g. Davies et al. 1994) but the scope of the present study necessitates a focus on broad-brush distinctions. For our purposes we simplify these fabrics into 'fine samian', 'fine other' and 'coarse' wares, placing individual forms firmly into one of these fabric categories if more than 90 per cent of records are of that type (see Table 5).

As 39 of 45 forms fall firmly into one of these categories there is clearly a strong association between form and fabric type. Fabric variation within a form is, however, probably slightly underplayed by the use of different codes for samian forms and their imitations (see Monteil 2004) and by a distinction in codes between flanged bowls in the coarse-ware black-burnished tradition (4M) and those variants predominantly made in other, often finer, fabrics (4Mx; Figure 3). As Monteil (2004, 3–5) pointed out, we should be alert to the idea that differences in fabric reflect distinctions in consumption behaviour as well as supply and she has shown some variations in the distribution of samian forms and their imitations within London, suggesting that they were preferred by different consumers. There is also a certain degree of difference in our state-code data among these forms, e.g. variable rates of wear and abrasions on 4Dr38 as opposed to 4Dr38IMI or lower rates of wear observed on 6Dr27 as opposed to 6A, but it is hard to state with confidence whether this indicates that imitations in other fabrics were used differently or whether such fabrics simply developed wear patterns more easily.

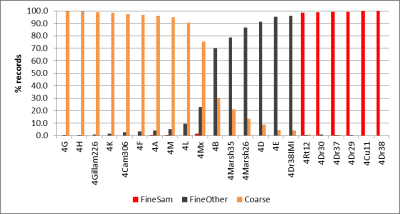

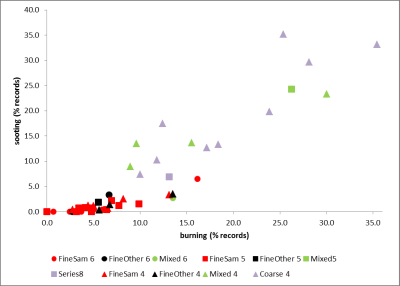

Most vessels within form groups 5 and 6 are made in finewares (Table 5, Figure 4 and Figure 5) probably reflecting the use of most cups, dish and plate forms as tablewares. However, some coarse- or mixed-fabric-category forms are also present even in these groups. Form group 4 is much more diverse (Figure 3) in fabric, and perhaps also function, encompassing forms characteristically produced in finewares and others that are typically made in coarse wares. The analysis of state-code data suggests that this may be a useful basis for distinguishing bowls used at the table from those used in cooking but that this distinction is probably not absolute, especially in the late Roman period (see below and Figure 12).

Six diverse forms appear in a more mixed range of both non-samian finewares and coarse wares (see Figure 6). These include morphological category B2 flanged bowls with foot rings (4B), B5 flanged bowls with flat bases (4Mx and 4Marsh26), P3 dishes (form 5J3) and C2 cups or small bowls (6A, 4Marsh35). When the recorded data for forms in this mixed fabric category were examined in more detail it became clear that Romano-British 'mica-dusted fine wares' were strikingly prevalent and it may be that this family of fabrics were more functionally diverse than other 'finewares' or that finer and coarser fabric variants in this tradition (Seeley and Drummond-Murray 2005, 120–3) might have been used differently. There is certainly future potential to explore the relationship between fabric and function at a more granular level.

Together with size and fabric, the shape and decoration of a vessel result from decisions and actions undertaken during manufacture. The forms discussed here represent recurrent combinations of these attributes, in designs that potters believed would be appealing or useful to consumers. Recurrent patterns or trends in terms of fabric, size and morphology may therefore reflect certain 'embedded' ideas about functions different forms would have needed to serve and, equally, what characteristics a pottery vessel that served such a function would need to have. It is no surprise that these variables are not entirely independent of one another.

Forms in the finer fabric categories vary widely in mean rim diameter, probably reflecting the range of functions for which such fabrics are suitable, from individual drinking vessels to large communal serving platters (Figure 6). Conversely, the size range of forms characteristically made in coarse wares is more restricted, with mean rim diameters typically above c. 160mm. This more limited range of sizes suggests a more restricted range of uses for these coarse fabrics, associated with fairly large capacities or interiors that were easily accessible to hands or utensils. This may relate particularly to the use of coarse wares in cooking but there is a significant overlap, in terms of rim diameter, with fineware forms that were probably used on the table (see below). Another suggested specific functional trend is that coarse fabrics may have been avoided for smaller drinking vessels, perhaps because they were considered less attractive for use at the table, less texturally pleasant for placing in the mouth or even because unslipped coarse fabrics may have been more permeable than slipped finewares (see e.g. Creighton et al. n.d., on the effect of fabric on the seepage of liquid fuels from lamps).

Our morphological categories (Table 2) encompass multiple forms that share aspects of shape and/or decoration. These forms are plotted together according to their mean rim diameters and the percentage of each manufactured in coarse-ware fabrics (Figure 7). These categories produce tighter clusters than form groups, suggesting that these typologically similar vessels will have had similar affordances and were produced as a result of similar sets of design ideas/constraints, probably to meet comparable requirements. In some cases they perhaps shared a specific intended function. Our categories do not form a perfect 'functional classification' and there is some variability. However, most outliers that differ in terms of fabric are the mixed category forms made in the mica-dusted wares discussed above (see Figure 6). Of these only 5J1/2 and 5J3 within morphological category P3 differ significantly in both fabric and size. Here a genuine difference in function is likely (see below). This simple approach using quantitative data seems to be a useful way of testing the cohesiveness of hypothetical functional classifications/groupings of forms in terms of their inherent qualities. Analysis of the state-code evidence below provides a way of testing such groupings using evidence for actual practice.

The character of state-codes, and some of their associated ambiguities, have already been discussed at a general level. The following sections consider patterns in the data for wear/abrasion, burning/sooting and residues, their direct implications for vessel use and some of the difficulties in their interpretation.

2.4.1.1 The development and recording of wear and abrasion and their distribution across the dataset

The development and recording of wear and abrasion and their distribution across the dataset 'wear' and 'abrasion', as defined in the state-code system (Table 3), both represent damage to, or removal of, the vessel surface. Only where this has been interpreted as actually resulting from use is this recorded as 'wear'. Clear usewear was recorded for only 368 records in this study as opposed to 2084 for abrasion. This scarcity may reflect the fact that only certain uses produce wear and that wear may not be present on unused or relatively new vessels. Perhaps more importantly, wear, unlike post-depositional abrasion, is likely to be localised, particularly on base interior surfaces, and thus subject to fragmentation/identification bias as discussed above.

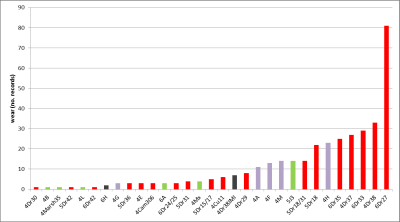

Because of the low counts involved, it is often rarer forms that show notably higher percentages of wear (greater than c. 1–2%). These data should be interpreted with care as in a few instances, such as forms 6H and 6Dr42, these percentages are strongly influenced by just a few worn vessels (Table 6, Figure 8). Conversely some forms with the highest counts of wear are extremely common vessels and here the worn examples account for a very modest percentage of total records. These include key 'cup' forms for which the presence of wear has been discussed at length in recent years, such as 6Dr27 and 6Dr33 (Biddulph 2008).

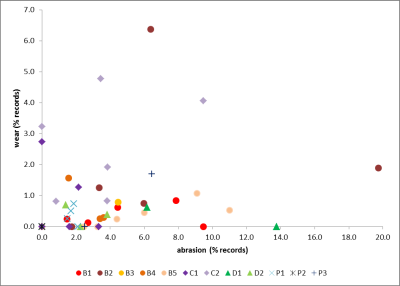

Abrasion data exhibits clear fabric trends, with samian forms tending to show the least abrasion, followed by coarse wares, and non-samian fineware forms showing the highest rates (Figure 8). This may reflect systematic differences in surface hardness/toughness between different fabrics. Abrasion may also remove or obscure wear, particularly on forms in softer fabrics. This may explain the very different proportions of wear and abrasion seen on 4Dr38 and 4Dr38IMI bowls, for example, which principally differ in fabric rather than form. A possible chronological dimension to abrasion patterns, reflecting the fact that late Roman pottery in London tends to be more frequently found in redeposited/residual contexts is discussed below.

Where wear is recorded, it is mostly on samian forms (Figure 8 and Figure 9).These have distinctive slipped surfaces which, given their low rates of abrasion, seem to be fairly resistant to incidental and post-depositional damage. The removal of such surfaces by usewear is thus more remarkable and results in colour/texture distinctions that are easy to spot, especially if strongly localised. While certain types of vessel forms, such as cups and flanged bowls within morphological categories C2 and B2, seem to exhibit higher wear rates than others, this prominence may be at least partially a reflection of the typical fabrics used (compare Figure 8 and Figure 10) and their size. There is certainly a marked fall-off in wear on forms with mean rim diameters of c. 145mm and above but it is difficult to determine whether an emphasis on these larger cups and small or medium bowls reflects as strong a functional pattern as it appears (Figure 11). Were vessels of these sizes appropriate for use as small mortars or for serving foods of types eaten with a spoon or similar utensil that left wear marks? Alternatively, perhaps this is an example of the type of fragmentation bias related to size/form mentioned above.

Wear among a series of very similar flanged bowls within morphological category B2 represents an interesting case study for these difficulties of interpretation. A clear difference can be observed between larger forms with flanges at the rim and lower wear rates (4Rt12, 4Cu11 and 4B) and smaller chronologically later forms with flanges further down the body and higher wear rates (4Dr38 and 4Dr38IMI) (Figure 11). Using our study data it is not possible to determine whether this is a genuine functional pattern, reflecting parallel changes in morphology and use over time, or a skewing effect resulting from the shift of a typologically diagnostic element, the flange, down the body towards the location of internal basal wear.

2.4.1.2 The interpretation of wear

Given the relatively small counts involved, the lack of precise description and the potential for fragmentation/identification bias, we are cautious about making general functional distinctions between specific forms based simply on recorded counts or rates of wear. This is unfortunate as recent studies of Roman material culture have shown that there is considerable potential for distinguishing and interpreting relatively subtle patterns in the location, type and intensity of use wear (e.g. Biddulph 2008; Banducci 2014; Swift 2014; 2017). Internal wear could reflect a variety of different activities such as stirring, scooping, mixing or grinding using different utensils such as knives, spoons, and pestles. External wear might reflect other aspects of how vessels were stored and used, including contact with different surfaces.

Our usewear dataset is not yet standardised or precise enough to sustain this level of analysis. It is clear that wear is predominantly internal but the simple presence/absence information and the inconsistent use of descriptive comments means ambiguity remains about the precise location, character and intensity of wear. Rim wear from lids and exterior wear may account for a small proportion of the data but presently their contribution cannot be distinguished, and we are essentially limited to noting gross differences in the presence of wear. This situation makes functional comparisons between forms very difficult but some intrinsic interest remains in the recurrent recognition of wear on specific forms that must reflect some aspect of how these forms were used (Figure 9). Notably our results here mirror those of previous studies of samian vessels where a particular emphasis on cups and smaller 'plain' flanged bowl forms such as 6Dr27, 6Dr33 and 4Dr38 are often noted (e.g. Willis 2005, table 58; Monteil 2005, 129, 153–4; Biddulph 2008; Monteil 2012, 344).

Other features of category C2 cups/small bowls and B2 flanged bowls with foot rings, may also suggest that they served a more utilitarian or heavy-duty function than certain other 'tablewares'. Forms in these categories exhibit decoration less frequently than the category C1 cups and category B1 bowls (Figure 1, Table 4) and, when not made in samian, can occur in coarser fabrics (e.g. forms 6A, 4Marsh35; 4B, Table 5, Figure 7) perhaps reflecting less emphasis on display and more on the practical use of these vessels.

Often these category C2 and B2 forms have flanges or complex rims that would facilitate a good grip (e.g. 4Dr38; 4B; 6Dr27; 6A; 6Dr35) and some examples of 4B bowls have obvious links to flanged mortaria normally regarded as kitchen wares for mixing/grinding (Marsh and Tyers 1978, 573–4, fig. 241 IVB.1). However, most category C2 and B2 forms either arguably comprised parts of matching tableware sets (Monteil 2005, 125–63; Webster 1996, 26, fig. 15; e.g. 4Cu11 and 4Dr35), or are paralleled by more expensive/decorative skeuomorphs in other materials (e.g. 6Dr27, 6Dr33 and 4Dr38; for glass examples: Price and Cottam 1998, 48–9, fig. 9, 53–5, fig. 12b, 109–10, fig. 43). This suggests that they were used at the table, even if they served a distinct function there, perhaps involving a heavier use of utensils, or if some examples had an alternate or secondary role in the kitchen. Monteil noted that samian cup forms often appear in two sizes (Monteil 2012) and in future it would be interesting to explore whether wear was associated with particular sizes. Interestingly 6A cups, which include examples in coarser fabrics, are more consistently worn than the 6Dr27 samian cups that they derive from/imitate and also have a slightly larger mean rim diameter. These larger coarser imitations may have been tailored for a specific function.

Wear is also recorded in some numbers for a few common larger forms, such as 4H bowls, 4Dr37 decorated bowls, and 5Dr18 platters (Figure 9). While only a small percentage of records for these forms show wear, the counts are sufficiently high to indicate that they were recurrently used in such a way as to produce wear. Closer re-examination of individual vessels may help to determine the type and consistency of wear marks and whether this recorded wear is unusually clear evidence indicative of general patterns of use or instead relates to alternative/atypical uses.

2.4.2.1 Distinguishing tablewares and cooking wares

The presence of burning/sooting should allow us to identify vessels that have been used for cooking. However, superficially similar effects, not always easily distinguishable using crude state-code evidence or from small sherds, could be produced by firing during production (Skibo 2015, 192). We have therefore excluded pottery from known kiln sites as at Northgate House (Seeley and Drummond-Murray 2005) from our dataset. Unintentional exposure of pottery to either domestic fires or large-scale conflagrations, such as those known in London during the Neronian and Hadrianic periods (Perring 1991, 22–3 and 72) could also have a skewing effect on rarer forms of appropriate date.

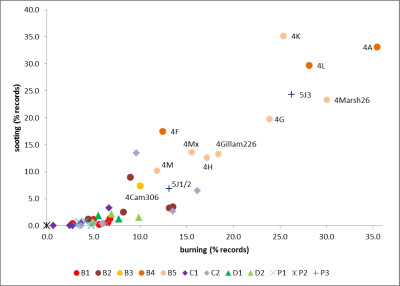

Unlike wear and abrasion, burning and sooting evidence exhibits a relatively clear positive linear correlation, suggesting that these state codes are frequently recorded on the same vessel types and that they are closely related phenomena (Figure 12). As might be expected, fundamental distinctions along fabric lines can be observed, with forms in the fine fabric categories exhibiting significantly lower rates than coarse- and mixed-fabric category forms, suggesting that these fineware forms were not routinely used for cooking. There are also hints of more subtle differences in the character of the heating evidence, with fineware, mixed-fabric and coarse-ware forms showing successively higher ratios of sooting to burning and thus sitting on slightly different trend lines. This could reflect distinctions in manufacture or how fabric types respond to heat, but may also indicate differences among certain fabrics/forms where burning results from accidents or 'one-off' ad hoc use, and others, especially coarse wares, used in such a way as to accumulate thicker sooty deposits from more intense heating or successive cooking episodes.

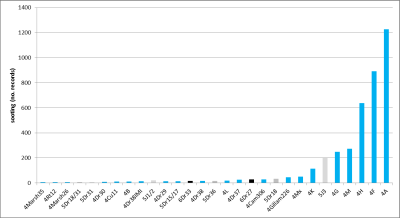

Sooting and burning rates for vessels from other sites in Britain have been collated at a general form-group level by Cool (2006, 38–9, table 6.1), who has shown that, after jars, open bowl and dish forms are the most common cooking vessels, followed by other enclosed forms such as flagons and beakers, with cups not figuring in her data. Among the open forms with sooting discussed here, the contribution of cups is negligible and the overwhelming majority with evidence for sooting are group 4 'bowls' with only one 'dish' form (5J3) making a notable contribution to the total sample of sooted vessels (Figure 13).

Our sample of bowls and dishes provides significantly more granular detail than Cool's study, indicating that a specific range of forms were used for cooking. As noted above, these are typically forms that appear predominantly in coarse wares and some of these, such as 4A bowls, exhibit very high sooting rates, rivalling or exceeding those of many jar forms.

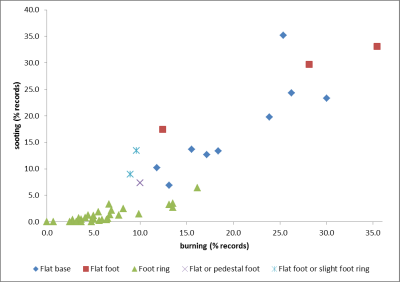

When the size of specific forms is considered, those with mean rim diameters of c. 160mm–220mm exhibit the highest rates of sooting (Figure 14). These are predominantly larger/deeper bowl forms within morphological categories B4 and B5 suggesting that vessels with higher capacities were preferred for cooking. As such they may also have been appropriate for cooking large or multiple portions or for boiling food. However, some shallower forms were clearly also used for heating food, including, perhaps, the more dish-like variants of category B4 and B5 forms as well as at least one exclusively shallow category P3 form (5J3). Shallow 5J3s likely had very different functional parameters, perhaps more suited to 'drier' styles of cooking such as baking/roasting or even frying. This form encompasses 'non-stick' imported Pompeian Red Ware dishes (Podavitte 2014) and if these dishes represent a style of cooking that made different demands of the vessel, this may help to explain why this form is found in a distinctly finer range of fabrics than most others with clear evidence for heating (Table 5).

The general unifying characteristics of those forms with evidence for heating are a coarse or mixed range of fabrics, fairly large mean rim diameters, and flat feet or flat bases. Conversely, the consistently low rates of heating evidence among vessels with foot rings, particularly those in finewares, is striking (Figure 15). Foot rings are designed to allow vessels to sit on flat solid surfaces, such as tables, and would also have served to raise the contents, minimising the base contact surface and reducing thermal conductivity between the contents and the surface beneath. This feature would have been ideal for tablewares but may have made such vessels less appropriate for cooking. While most of the flat-bottomed forms are characteristically made in coarse wares, some belong to the 'mixed' fabric category (e.g. 4L, 4Marsh26 and 5J3), and some fineware examples of these forms were used for cooking. As such, this distinction in base morphology is probably not just a technological difference between different pottery industries but an active choice relating to the intended function of different forms.

Sooting/burning on fineware forms with foot rings is scarce but it is not completely absent and there is a certain amount of consistency in the forms on which it has been recorded (Table 6, Figure 15). Among the group 4 fineware bowls sooting is more common on morphological category B2 flanged bowls than on category B1 decorated bowls, and among group 6 'cups' it is more common in category C2 than C1 cups. These distinctions could complement those noted in relation to the wear evidence above in suggesting B2 and C2 vessels could have alternative functions away from the table. Among fineware group 5 forms, category D1 and D2 dishes typically have higher sooting rates than P1 plates although the absolute numbers are again very small.

Re-examination of these sooted fineware vessels might determine how consistent such patterns of use were, and their implications for the circumstances under which these tablewares became burnt/sooted. While fine tablewares may have occasionally been used for cooking, it is not clear whether some forms played a specific secondary/alternative role in food preparation/cooking or, given the low counts involved, whether certain forms simply leant themselves better to ad hoc reuse or repurposing in the kitchen, perhaps when old or damaged.

2.4.2.2 Exploring variations in function among coarse- and mixed-fabric forms of bowl and dish

In addition to the strong fine/coarse ware distinction seen in cooking evidence, and the associated distinction between presence and absence of foot rings, there is a considerable range of both burning (9–35.4 per cent) and sooting rates (6.6–35.2 per cent) among the coarse and mixed-fabric bowls and dishes, suggesting some forms were heated more frequently than others (Figure 12 and Figure 16). The ratio of sooting to burning is typically higher on category B4 forms with curved sides and flat feet than on the category B5 and P3 forms with flat bases (Figure 16). This suggests that the major differences in body/base shape are related to functional distinctions, perhaps different styles of cooking, but it is also conceivable that they fragment or collect soot differently.

Those with the highest sooting and burning rates include morphological category B4 bowls (forms 4A and 4L), B5 bowls (forms 4G, 4K, 4Marsh26) and P3 dishes (form 5J3). All these forms were probably routinely used for cooking.

Some common coarse- or mixed-fabric forms exhibit modest percentages, but sometimes with very high counts, of burning and sooting, e.g. forms 4F, 4M and 4H (see Table 6 and compare Figure 13 with Figure 16). These forms were clearly regularly used for cooking but the higher proportion of unsooted examples compared to the morphologically similar forms already mentioned, may indicate that they also played a more important role elsewhere in the kitchen or on the table.

Within morphological category B4, form 4F notably exhibits lower rates of burning and sooting. There is a reasonable amount of diversity encompassed within this form code that is not always apparent from the rim (see Marsh and Tyers 1978, 574–5, fig. 241 form variants IV.F.1–6) and some examples of these 4F hooked-rim bowls have decoration that is absent on other category B4 bowl forms. 4F bowls also exist in shallower more dish-like variants with a wider foot that begins more closely to resemble the flat-based body shape found on category B5 and P3 forms rather than other category B4 forms such as the deeper carinated or hemispherical 4A bowls.

Other coarse forms, such as 5J1/2 decorated dishes with flat bases, again exhibit low rates of sooting evidence but based on even more modest counts (Table 6) and so may have only very rarely been used in the heating of food. Despite their coarse fabric, their size and basic body morphology is comparable to some morphological category P1 plate/platter forms, which are made in finewares and have foot rings, suggesting they may have been suitable for serving similarly-sized food portions. Equally they are markedly smaller than the morphologically similar but undecorated 5J3 dishes that appear to have been used for cooking.

Our general impression, then, is that those morphological category B4, B5 and P3 forms that exhibit lower rates of evidence for heating are often shallower or smaller forms (Figure 14). These may also have been used for serving food at the table, and this may explain why they seem to have been decorated more frequently than other morphologically similar forms.

A fuller understanding of distinctions in use among these types requires both more detailed recording of sooting/wear patterns and for the state-code evidence for use to be systematically related to other variables such as fabric, size and shape on a vessel-by-vessel basis.

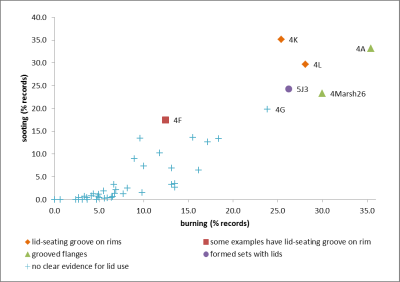

2.4.2.3 Evidence for the importance of lids in urban cooking practices

One further aspect of vessel function, the use of a lid, is strongly associated with evidence for heating, based on our data. Lid-use can be recognised from lid-seating grooves on the top/inner edge of the rim, e.g. on 'Surrey bowls' (form 4K) or on the top of the rim/flange, e.g. on 'reed-rimmed' bowls (form 4A). The use of lids on certain other forms that lack such features can be demonstrated when sets of vessels/lids in matching sizes and distinctive fabrics can be identified, e.g. Pompeian Red Ware 5J3 dishes (Podavitte 2014, 123, fig. 1).

Using such criteria, lid-use is suggested for a high proportion of the most heavily sooted/burnt forms (Figure 17), suggesting a strong link between lid-use and cooking. Of course lids may also have been used with other forms, and systematic recording of sooting and wear patterns could help to determine their wider prevalence and the strength of this association (Banducci 2014, 191 and 202). 4G flanged-rim bowls with flat bases that plot close to the lidded forms in terms of heating evidence in Figure 17, but have no explicit typological provision for a lid, are an obvious target for more detailed examination.

Lids themselves (form code 9A) exhibit average burning rates of 21 per cent and sooting rates of 22 per cent, supporting this strong connection with cooking. This has been rather under-emphasised in recent discussions, which have identified a strong bias towards urban sites in lid use but discussed this principally in terms of lidded jars, interpreting them as transport containers brought from rural areas (Perring and Pitts 2013, 155, fig. 7.15 and 156–7; Pitts 2016, 726–9, fig. 35.2). Our data suggest that cooking 'bowls' and 'dishes' need to be integrated into this debate and that lids reflect distinctive urban cooking practices. Furthermore, while some jars may have been used to transport foodstuffs (see also Biddulph 2016) it is likely that lid-seated jar forms were also used for cooking as they are often found with sooting; for example two jar forms defined specifically on the basis of morphological provisions for lidding exhibit fairly high burning and sooting rates in London: 2J (burning 38.9 per cent; sooting 25.6 per cent) and 2x (burning 20.5 per cent; sooting 23.3 per cent; see MOLA 2014 for more details of these forms).

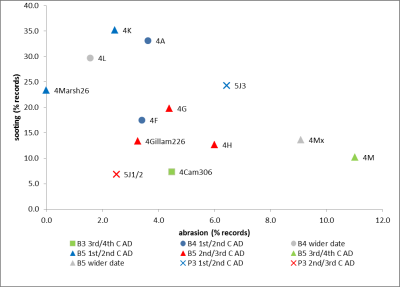

2.4.2.4 The decline in evidence for heating on coarse-ware and mixed-fabric bowls and dishes over time

Chronology seems strongly related to the use of coarse-ware and mixed-fabric forms. There is a relatively uniform pattern by which sooting/burning rates for coarse-ware, and mixed-fabric bowls and dishes are higher on those forms in use in the first/second century, while the percentages of vessels with evidence for heating declines for similar forms in use during the middle and later Roman periods (Figure 18).

Several factors could exaggerate this effect. The most intense evidence for pottery production (Seeley and Drummond-Murray 2005; Rayner 2016), and for major fire horizons in Roman London (Perring 1991, 22–3, 72), is concentrated in the first and second centuries CE. However, we suspect that burning/sooting from these sources is rare enough that it could only seriously skew the evidence for rare forms. Potentially more important is the shift in the character of depositional/post-depositional processes in later Roman London, late pottery often being heavily abraded/fragmented and found in dark earth or residual in medieval pits (Symonds and Tomber 1991, 84). High rates of abrasion have been recorded for some late forms and such taphonomic processes can remove/obscure evidence for heating (Beck et al. 2002), perhaps explaining why sooting rates and abrasion show some signs of being negatively correlated (Figure 18).

It is probable, however, that a real pattern exists here that could relate to broadly contemporary changes in the supply of pottery and in the repertoire of vessels typically found in site assemblages. Cool argues that many later Roman assemblages in Britain were dominated by jars and bowls and that by the later fourth century the diversity of forms available typically diminished (2006, 227–235). To some degree a similar simplification in vessel range can be observed in Roman London (Symonds and Tomber 1991), although regional variation is clearly significant and more work is required to fully characterise the nature of these changes (Evans 2016, 522–5).

Our analyses suggest that certain late coarse-ware and mixed-fabric bowls and dish forms may have served on the table and in the kitchen, e.g. 4M flanged bowls with flat bases. More specifically, the decline in sooting rates over time between morphologically comparable forms (Figure 18) may suggest a long-term shift in emphasis away from cooking. Such forms may have become more multi-functional, playing a more prominent role on the table over the length of the Roman period, perhaps partially replacing more specialised fine tableware forms. There is considerable potential here for further research, focusing on selected well-dated late Roman assemblages with minimal abrasion, to compare chronological trends in burning/sooting patterns, across both open forms and jars, with any contemporary shifts in the relative abundance of different forms.

Another late Roman coarse-ware bowl form with fairly minimal evidence for use in heating is 4Cam306 (Table 6, Figure 16 and Figure 18). This is the only member of morphological category B3 and its simple beaded rim, the narrower pedestal foot found on many examples (e.g. Rayner and Seeley 2008, 189, fig. 4.3.2, no. 18) together with its mean rim diameter, the smallest of any coarse-ware form in this study (Table 5, Figure 7), distinguishes this form from the other coarse cooking bowls/dishes.

Given the low rates of state-code evidence, this form is a good example of the limitations of the kind of data considered in this article for more detailed functional interpretation of vessel use. It is necessary also to consider additional classes of qualitative and contextual evidence to develop a more complete and nuanced understanding of the use of this vessel form. The very crude manufacture of these vessels has been noted (Rayner and Seeley 2008, 186, table 4.3.1), and in London and elsewhere they sometimes appear together in large quantities, implying these were cheap and disposable. Often these assemblages come from religious sites or votive deposits, perhaps deliberately smashed (Haynes 2008). The possibility that such vessels were produced specifically to be destroyed in a votive context should be considered but an alternative, not mutually exclusive, interpretation is that they represent a sort of cheap, disposable, low-quality tableware, used during episodes of large-scale communal feasting and then disposed of afterwards.

Residues were noted for 184 records, but due to the small sample and ambiguity of this evidence, they are only discussed briefly here. Only 69 records provide a more detailed description of the type of residue in the comments field and these were highly variable in levels of detail and terminology. A more standardised and precise approach to recording residues is required.

Fifty-six records are described as black or charred residues. Appropriately, the only forms with more than ten records of residues are coarse-ware bowls that also show signs of burning/sooting: 4A, 4F, 4H and 4G and 4K (Table 6). Some of these vessels could usefully be re-examined to determine whether such residues simply represent misinterpretations of sooting or actually represent distinct phenomena, e.g. charred food on the interior. Regardless, it might also be significant that, proportionally, residues appear most frequently on 4L and 4K forms, both of which have lid-seating grooves.

However, at least three other types of residue can be distinguished within the comments fields of the database. Limescale was noted within at least two 4A reed-rimmed bowls, perhaps indicating use for boiling liquid. Vessels of this form, which frequently show evidence of heating (Figure 13, Table 6), have a depth and volume appropriate for containing liquid. It would be interesting to re-examine undefined residues to see if limescale was restricted to this open form or to vessels of similar size and shape (i.e. vessels with curved sides and flat feet within morphological category B4) or similar depth. Pink/red material, perhaps pigment, was found within at least two 4A bowls and four 4F bowls. Mortar was noted within one 4G and one 4F bowl but it is not clear from the description whether this might be post-depositional. Clearly some of these larger coarse-ware-style vessels were used for functions not associated with the preparation or consumption of food.

The analysis above shows that MOLA spot-dating level records, produced as part of basic quantification and dating of site assemblages, can usefully be applied to questions about vessel function. Despite their rather coarse nature, the state-code data provide strong evidence for functional variation within the sample of cups, bowls, dishes and plates discussed here. This includes broad distinctions, in fabric and form, between table and cooking wares and the recognition of wear on a range of tableware forms similar to those previously recorded elsewhere. However, some subtler trends that deserve more research have also been uncovered, such as the strength of the relationship between cooking forms and the use of lids and a possible shift in the use of coarse-ware and mixed-fabric bowls and dish forms over time, which suggests they came to play a more important role on the table in the late Roman period.

The recording system was not designed for complex functional analysis and many ambiguities and limitations within this dataset have been highlighted. These include a lack of standardisation/precision in state-code recording, the potential impact of underlying variations in fabric on analyses of form, and a seeming bias resulting from the disarticulation of typologically diagnostic elements of vessels from those parts where wear or sooting patterns occur.

Ways to combat these problems are currently under consideration and will necessarily involve establishment of a more precise and objective system of use-alteration/state-code recording within a zonal system that distinguishes their distribution across the different elements of the vessel. This will allow for more confident and subtle interpretation, and zonal data could be used to distinguish 'crude' and 'true' prevalence for pattern of wear and sooting on different elements, similar to those utilised in studies of pathology on human skeletons, for example (Roberts and Cox 2003, 20). This would significantly reduce the impact of fragmentation/identification bias.

The methodology advocated by Banducci (2014) for recording use-alteration provides a valuable model but it remains to be determined whether a similar system could sensibly be integrated into MOLA's basic pottery recording methodology. This system needs to allow for the efficient treatment of entire site assemblages, which are much more diverse and often hundreds of times larger than Banducci's targeted studies of specific forms and fabrics. However, a targeted study of 4F bowls from London, more comparable in scope to Banducci's work, is currently under preparation by Amy Thorp (pers. comm. 2017) and will help to assess the practicalities of this type of detailed use-alteration recording within the MOLA system.

Among fine tablewares, the quantity of, and variation within, state-code evidence is less substantial and our interpretations have been correspondingly limited. While more detailed studies of wear may improve our understanding of the uses of specific forms, the discussion of 4CAM306 bowls above and Monteil's (2004; 2005; 2012) study of samian in London shows that other types of metric, typological, chronological and contextual study can be applied to unpicking more detailed functional trends within the dining repertoire. Since 2016 quantification by EVEs and collection of metric data has been undertaken as standard, in order to facilitate such research and statistical analyses of London assemblages more generally.

Broad form groupings, similar to the numbered London groups, have been used successfully to identify and analyse large-scale differences in ceramic consumption (e.g. Evans 2001) complementing other similar approaches based on fabric (e.g. Booth 1991). In London these have even been used to explore functional variation between assemblages from specific excavations, buildings or features (e.g. Davies 1996; Groves 1996; Gerrard et al. 2011). The use of a hierarchical typology facilitates such approaches from the perspective of data manipulation and also allows us to integrate smaller, less diagnostic, fragments or unusual one-offs by recognising that they are a 'bowl' or belong to form group '4' even if they cannot be assigned to a specific form code. Another outcome of this study, however, is clarification of the evidence for significant functional variation within some of the London form groups. Cups, bowls, dishes and plates are all potential tablewares but it is clear that many of the 'bowls' within group 4, and at least one of the shallower group 5 'dish' forms, were actually used in cooking. This fundamental functional distinction is not therefore being clearly addressed by analyses of assemblages at the form-group level.

Clearly more detailed studies of consumption, exploring specific cooking and dining practices, will need to analyse assemblages on the basis of more selective sub-sets of data (e.g. Monteil 2005; Pitts 2014) and/or at higher resolutions, on the basis of variable criteria chosen to reflect finer functional distinctions. The morphological categories used in this study are one example of a complementary/alternate scheme for organising data. However, no such scheme is perfect and, as there will always be some ambiguity associated with forms of multiple or uncertain function, it is important that we record and publish our data in a way that allows them to be divided and recombined to address different questions. It is much harder to split lumped data than to lump it together again (Orton et al. 1993, 77–9) and so we need to ensure that distinctions that may become important at analysis are recognised in the way that we record vessels. The London typology is fundamentally reliant on the presence of rims, so base fragments or other less diagnostic sherds are typically assigned only to a form group e.g. '4' or to a range of possible form groups e.g. '4/5'. Such broadly defined codes serve to blur distinctions within form groups and information about features such as body/base shape, or the presence/absence of a foot ring, which our analyses suggest may be functionally significant, is essentially lost.

The resolution of this problem in the future may require the introduction of new form codes to cover categories of less typological diagnostic fragments or the recording of certain kinds of morphological data in a manner that is distinct from typological coding. For the present it is important that distinctions being made typologically are retained in published data and that, even when assemblages are summarised at the form-group level, more detailed breakdowns by form and fabric are available. In the past this approach has not always been practical and where the time has been invested (e.g. Rayner and Seeley 2002, 162–204) it has resulted in very large pottery reports that are not suitable for all publication formats. However, these problems are increasingly surmountable now that large quantities of data can be manipulated, and potentially published, digitally.

Much of our work in London is intimately tied to the quantification, dating and publication of site sequences and assemblages from specific excavations within the framework of developer-funded archaeology. Our recording systems reflect these requirements and, in the past, have been focused on defining the chronology and development of specific pottery industries and forms and the establishment of broad-brush functional distinctions between excavation assemblages, relatively few of which could support the more detailed functional analyses undertaken here in isolation. Writing this article has constituted a valuable opportunity to consider different kinds of questions as part of a wider meta-analysis, but such analyses are only possible on the back of site-by-site recording in a way that is consistent and mutually comparable. Conversely, it is only by undertaking wider research that the issues and opportunities that different data-recording methodologies present become apparent, allowing for the iterative development of best practice.

Adapting and expanding our approaches in the future will support different types of research on pottery use and consumption patterns, but our results demonstrate that the existing data also have significant untapped potential and can point us in the direction of new avenues for research. The challenge for the future will be maintaining comparability with these important 'big' datasets, produced over nearly 40 years of research, while also building on their legacy.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.