Cite this as: Groenendijk, H.A. 2019 Farmers and Archaeologists: any shared interests? Best practice from the Dutch countryside, Internet Archaeology 51. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.51.1

Farming in a country like the Netherlands, with its limited surface area, high land value and critical customers, is like walking a tightrope: a farmer is always the scapegoat when it comes to the societal consequences of the job. Archaeologists, for example, have problems with modern cultivation techniques, because they harm archaeological sites. The farming community on the other hand can be reluctant to accede to requests from archaeologists, since it has many more and larger issues to overcome, such as drastic environmental restrictions. Feeling obliged to swallow archaeological restrictions too is just one bridge too far. Long before the public debate on environmental issues emerged, an increase in both the scale and pace of technological change had led to a massive shutdown of farms and, consequently, a decrease in maintenance of these proud, monumental farmhouses. Moreover, specific regions in the north of the Netherlands suffer from a severe decline in the number of inhabitants. Working in the province of Groningen, over the last 35 years I have seen many farmsteads become derelict. When a Groningen farmer leaves their property in a state of disrepair (Figure 1), this can be considered as a silent SOS to the outside world.

Taking an interest in the social aspects of the farmer's position, I try to imagine what it means for a farmer to make a living on top of a classified monument, in a classified landscape, under the permanent pressure of regulations devised by heritage authorities, who tell you what is so unique about your plot, and that intervening in your management is in the public interest. Of course, for the farming community the loss of archaeological information is nothing compared to the shutdown of farms. In addition, in Groningen the recent earthquakes, caused by gas extraction, affect both heritage matters and the confidence in authorities. The readiness to cooperate dwindles noticeably. Yet, concerned archaeologists have a point in making their voices heard.

In the Groningen coastal zone, little affected by the building urgency that so characterises the west of the country, we find sediment-covered sites, prehistoric dwelling mounds, river-beds, dikes, rural buildings, ancient land-reclamation and settlement patterns in their original spatial setting (Figure 2). Yet, here too modern farming prevails and the combination of high-tech agriculture and heritage management is at best a marriage of convenience.

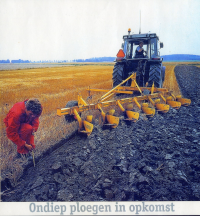

After signing the Valletta treaty but long before 2007, the year when the treaty was implemented into Dutch legislation, the province of Groningen realised that something had to be done to slow down the creeping erosion of their major sites, namely the raised settlements or terps, most of them being classified monuments. In 1994, a participatory project (Sympathieprojekt) called Wierden en waarden ('Terps and values'), was set up to achieve a better understanding within the farming community for the growing concern among heritage keepers. Modern ploughing and scaling-up had led to a significant levelling of the artificial terp mounds and to a decline of landscape characteristics. An ever-increasing flow of fresh surface finds reported by amateur archaeologists, particularly large pot sherds and remarkable metal objects, testified to the loss of in situ information (Figure 3). Our more or less academic approach to tackle the problem of the observed erosion might indeed have been correct, but the farmers deemed responsible did not share our arguments about whatever degradation took place on their farmland. 'How would you officials know?' they reasoned. Distrust is understandable whenever authorities launch a project, and it was only by offering attractive arrangements, and with the help of those in the vanguard, that our attempts to carry out erosion-cutting measures yielded some fruit. Shallow ploughing was one of the options, reducing the water run-off to avoid washing away soil particles. However, providing a so-called eco-plough did not lead to its permanent use, though it yielded the same product volume while reducing fuel consumption and fertilizer expenditure and keeps the soil in a better condition (Figure 4). A main drawback was the term of the project, namely limited to four years for political reasons, and when the project stopped the participants reverted to their daily routine. The 1994-1998 project failed to plan a follow-up.

However, what we learned from this project is that field demonstrations with the aim of diminishing land degradation should be conducted under the aegis of an Agricultural Advisory Service and through doing so, explaining archaeological issues may count on a better support within the agro-community (Figure 5). We also learned that issues like ploughing parallel to contour lines to slow down the water run-off was considered utterly impractical in the efficiently block-structured farmland, and therefore had to be abandoned completely. Most of all, however, farmers hate discontinuity and regulations that thwart their business planning, which was precisely the weak point of our first participatory project.

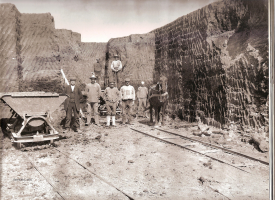

At the turn of the 20th century, the Province of Groningen had tested the possibility of 'restoring' some of the heavily damaged sectors of terp mounds that had been quarried by previous generations to earn money from selling the fertile soil, leaving steep escarpments (Figure 6). The idea was to fill up those sectors with soil of a different provenance. It must be said that their present derelict state is an eyesore to landowners and heritage managers alike, as the dug-away areas are uneconomical, low-lying plots of land, while the terp remnant slowly subsides, lacking a counterfort. Acquainted with the Wierden en Waarden project, several farmers asked the provincial authority for help. The Englum case may illustrate the necessity of a customised restoration plan. Here the landowner was motivated only by economic considerations and had no sense of archaeology whatsoever – and was very honest about that. At the same time, the province of Groningen saw an opportunity for making a virtue out of necessity by using dredging material from the nearby River Reitdiep, the maintenance of this waterway being the task of the provincial authority (Figure 7). From a heritage management point of view, the ongoing drying and collapse of the Englum terp escarpment had become a serious problem. Taking these together, the project started with an examination and excavation of the base of the terp as well as of the exposed escarpment.

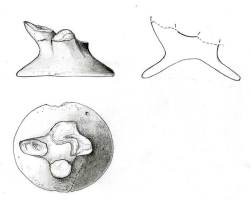

The base of the terp, whose deepest features had survived the quarrying of the early 1900s, still gave information on the earliest habitation, which had started in the 5th century BC. The profile of the escarpment gave insight into the degree of preservation of soil features, indicating that those features in the upper part of the escarpment had suffered considerably, caused by desiccation and oxidation (Nieuwhof 2007) (Figure 8). The whole process of pumping in 120,000 cubic metres of dredge, its settling and shrinking, and the final covering of the artificial terp with its original topsoil, took six years altogether (Figure 9). Expenditure on the whole procedure was covered by the province of Groningen. When the job was completed, both the farmer and his son had become true advocates of archaeology. They now tell visitors about the exciting discoveries made on their property with the help of an information panel, donated by the Dutch Automobile Association ANWB. At Englum, a true exchange of benefits has been accomplished (Figure 10).

Meanwhile, five other damaged terp mounds have been 'repaired' under strict conditions, for there will always be a category where filling-up is undesirable, such as the Ezinge terp, where the doyen of modern Dutch archaeology, A.E. van Giffen, conducted his famous excavations 1923-1934. Ezinge became the icon of terp research in the Netherlands and beyond and so is kept in the state Van Giffen left it in the 1930s.

At the turn of the 20th century, 87 severely damaged Groningen terps were considered for restoration or even reconstruction, with 32 being rejected due to the intrinsic educational value of the dug-away section e.g. Ezinge. There were emotional considerations as well. Many a low-lying sector has been converted into a village ice-rink with a corresponding affection on behalf of the village inhabitants, adn so this was also considered a criterion for non-completion (Groenendijk and Meijering 2006) (Figure 11). In any case, restoration may only take place if a landholder applies for it, as it is not subject to a top-down programme. Once restored, the win-win transaction in the terp zone is the improvement of arable land, the rehabilitation of a landscape feature, the archaeological benefits and the protection of the remaining body of the mound against solifluction and atmospheric oxidation. This multifaceted approach proved very successful, with lasting positive effects in a technical sense, as well as establishing goodwill among the local population. Investing time in a communal interest often starts with engaging key figures. Entrusting responsibility to local people works out well for terp mounds, as modern inhabitants of these raised settlements mostly recognise their shared responsibility for the subsoil of their premises (Groenendijk 1997). This does not automatically apply to other visible archaeological objects, such as megalithic tombs, as here the interest group is definitely smaller. Even more difficult is raising public sympathy and awareness for the unseen heritage. Such sites lack outwardly visible characteristics, especially those situated in arable land and subject to regulations that are not understood if heritage keepers keep rigidly to the axiom 'preservation for future research' (which in practice means: leaving untouched forever). Individuals or communities involved have to be continuously taught about the necessity of keeping the soil archive, which does not mean simply abandoning all research on a specific site.

The Valletta Treaty, implemented in successive Monuments Acts and shortly to come into operation in the Netherlands as the Environmental Act (Omgevingswet), does not offer solutions for endangered sites lacking a clear 'disturber', and as a matter of fact these sites find themselves beyond the reach of the treaty.

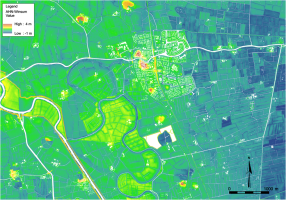

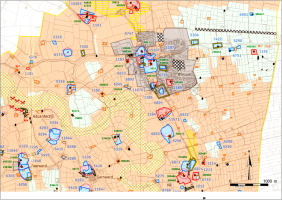

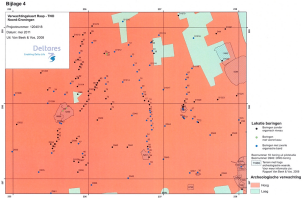

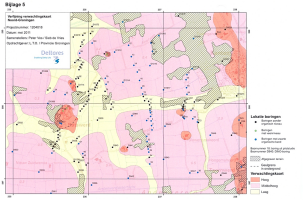

In the Netherlands, a new societal obstacle was introduced c.2000, as development-led archaeology was accompanied by a predictive model of foreseeable archaeological values, meaning an educated guess of what could be encountered in terms of features and finds outside the listed sites. The predictive model (in Dutch: verwachtingskaart) was converted into a research obligation before a building permit could be given, if a building development was situated within an archaeological risk zone. This new regulation led to absurd claims towards landowners. If we compare the contour map of a salt-marsh municipality in the north of Groningen with the predictive map of the same area (Figure 12a and b), one can imagine this would rouse public opposition, most of all amongst farmers. In order to ease anxieties, in 2010-11 a pilot project was carried out by the province of Groningen, by coring a selected area of 6km² that was a high archaeological risk, but this did not meet user requirements. The definite mapping of real archaeological features was a correction compared to the predictive model, but did not result in an improvement from the landowners' point of view. The result, a threefold hazard classification (low, average and high risk) proved not really workable and the pilot was too costly to be continued (Figure 13). This project, meant to address the farmer's needs, failed for lack of a customer-friendly applicability.

The general farmers' organisation LTO (Land- en Tuinbouw Organisatie), which participated in the Groningen coring pilot, tried another approach. Farmers were invited to have their properties inspected to ascertain the degree of depletion of the soil profile, in the belief that a disturbed profile is worthless, archaeologically speaking, and therefore free of archaeological claims. In several respects this was a dangerous assumption, not least because it could be regarded by the landholder as an incentive to disturb the soil profile. The following example illustrates the delicacy of this approach.

In the former peat reclamation district of Groningen, now a sandy region, Mesolithic sites are situated on coversand ridges, their crests already ploughed as deep as the B-horizon of the podzolic subsoil. Figure 14 shows an excavation campaign on a vast Mesolithic site, where degradation by traditional ploughing has reached the brown podzolic B-horizon; only the flanks of the dune show an intact old surface, illustrated by the grey podzolic E-horizon. Yet this certainly damaged site should not be disregarded altogether. Features such as Mesolithic hearth-pits, an important source of anthropological and environmental information in our sandy districts, are still to be encountered. What if the farmer simply decides to plough 20cm deeper or use a special device to favour plant rooting? They would improve productivity and at the same time get rid of a technical obstacle – and, what is more, nobody would notice. This is a horrifying prospect for archaeological heritage managers, and a way of conduct impossible to control.

Instigated by LTO, several renowned archaeological firms decided to cooperate in an endeavour to accelerate the improvement of predictive maps in December 2017. The archaeological business community welcomes this initiative for deregulation, but heritage managers have a range of views. Do we get something in return? Personally I fear a one-way affair with a negative impact, a trivial victory over bureaucracy, instead of seizing the opportunity to transform the amelioration of the predictive map into a participatory project. I miss an exchange of benefits, literally the reward for not eliminating the fragile Mesolithic soil archive. The paradox is that we all strive for fewer rules and regulations, landowners and heritage keepers alike, but unconditional confidence in mutual respect has regrettably proved naïve. Self-management does not work out well in current Dutch society, and mutual respect has to be earned, as it is a question of give and take.

Ample experience has been acquired with heritage management on terp mounds, those compact humanity heritage sites that go back twenty centuries or more. The present terp inhabitants became familiar with negotiating with authorities after decades of archaeological claims, shifting government policies and special protection arrangements. On the heritage manager's point of view, the decades-long learning process has led to a well-considered approach, accumulating best practice. The pioneer of archaeological heritage management, R.H.J. Klok, underlined the necessity of taking the terp's surroundings into account as early as the 1970s (Klok 1979); stressing shared responsibilities that came up at the turn of the 20th century (Groenendijk 1997), a recent terp village project, conducted by the University of Groningen, involves local people setting up local research programmes (Wiersma et al. 2015). Now that officials have succeeded in monitoring shared interests of modern terp inhabitants, do farmers and archaeologists have shared concerns and interests in the surrounding countryside too?

A widely felt concern is looming that in traditional agriculture things have to change. Also within the agro-branch itself attitudes are shifting, although pressure comes mainly from a social angle, with sustainability and healthy-ageing as key words. Nature-inclusive farming is one aspect of this changing attitude and we archaeologists cannot miss the boat on that. Concern may turn into partnership and may arrive at coalitions with interest groups that formerly were considered the farmers' adversaries. But how do we channel this shared concern?

A recent participatory project Zonder boer geen voer ('Without farmers no food') in the province of Noord-Brabant has drawn publicity. This two and a half year project comprises a travelling exhibition, displaying 5000 years of indigenous food production, which was presented in supermarkets and garden centres (Figure 15). A point of reference is the mutual and stubborn incomprehension between farmers and consumers, as well as between farmers and archaeologists. The fundamental notions it offers are sustainable food production, the meaning of local archaeology, as well as the interdependence of urban environments with their surrounding countryside through food. This initiative reaches producers and consumers in their vicinity in a trusted location, and proved an eye-opener for many visitors.

My personal contribution as an academic teacher is to reach out to young farmers and farming contractors. I consider middelbaar beroepsonderwijs (Intermediate Vocational Education) the level most suited to bring about empathy for heritage matters and to generate a joint responsibility on behalf of future agrarians, in short those in charge of farming equipment (Figure 16). The target group is about 18 years old, a future owner-occupier or agricultural worker, with an outspoken practice-orientated mentality, full of energy, both open to new approaches and sceptical when the farmer's interest is at stake. The University of Groningen has taken action in setting up an archaeological module together with MBO Terra Groningen as part of their curriculum. Of course we need our academic students to attend. We already teach them political sensitivity, communication skills, dealing with opposition and to keep an eye open for the current Dutch trend of deregulation (in short, we teach them flexibility). But a first encounter with MBO Terra students showed an utterly different perception of 'heritage'; which was regarded first of all as an obstacle that happens to be embedded at the core of their daily lives. Academic masters students are not so familiar with such opposition to a subject of study they themselves chose from conviction. A clash of basic thoughts will be inevitable at the start, but the challenge is not to be discouraged too quickly: a lesson in flexibility. This is my present answer to sustainability in heritage matters: give farmers' property a historic context and the farmers themselves a heritage responsibility. We should not forget that the majority of archaeological sites lie in arable land, even in a country as crowded as the Netherlands! We know that mobilising this interest group is not without risks, although it requires a permanent maintenance as well as investment in confidence.

To end, I have some general rules-of-thumb as to how to organise archaeological sensitivity beyond the professional circle. It resembles the consensual Dutch approach known as the 'polder model', but maybe generates some broader spin-off.

In the Dutch polder, where archaeology has come to maturity since the Valletta treaty was signed, everybody wants to be terribly equal and exercise mutual respect. Yet a safety net by ensuring continuous guidance and appreciation, whether by governmental organisations, NGOs or private firms, is missing. This I consider one of the major challenges for a generation of heritage keepers to come.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.