Cite this as: Howard, A.J. 2019 Environmental Archaeology, Progress and Challenges, Internet Archaeology 53. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.53.1

The collected essay papers published in Environmental Archaeology: Meaning and Purpose (Albarella 2001), provided an opportunity for a range of heritage specialists including academics, curators and field archaeologists primarily based in the UK to reflect on the health and status of environmental archaeology within the broader framework of the discipline. The volume was published within a timeframe that provided the authors with the opportunity to reflect and draw upon the effects of two key drivers with the potential to shape the development of environmental archaeology during the preceding two decades.

The first of these was the implementation of Planning Policy Guidance note 16 in 1990 (Department of the Environment 1990) and the commercialisation of archaeology, which has largely driven and sustained the expansion of the environmental archaeology profession. The second was consideration of the effects of five preceding Research Assessment Exercises (RAE 1986, 1989, 1992, 1996, 2001) undertaken across the UK university sector, which had focused and continues to focus the minds of UK-based academics on the quality, outlet and speed of research publication. While the first of these themes was explored in the 2001 publication by Gwilym Hughes and Andy Hammon, the second received notably little, if any, mention by volume authors.

The introductory chapter by Albarella (2001, 4) suggested that 'there is still a profound fracture existing between archaeologists dealing with the artefactual evidence and those engaged in the study of biological and geological remains'. The concluding comments of Barker (2001) echoed this concern and pressed the need for environmental archaeology to be considered as a core activity of any research project. Post-2001, the challenges of dovetailing the bioarchaeological record with what are often considered more mainstream archaeological activities, particularly within the commercial sector and planning framework, continue to be highlighted; for example, Hall and Kenward (2006). However, a number of studies have also demonstrated the value of the environmental record and its potential to answer major research questions across the discipline (Fulford and Holbrook 2011; Van Der Veen et al. 2007; 2013).

Such concerns regarding how environmental archaeologists, or perhaps those more broadly described as archaeological scientists, are integrated within the wider framework of pure and applied archaeological research is not a problem unique to the UK; for example, over the past 40 years in the USA, a number of eminent geoarchaeologists have written commentaries that have sought to consider and clarify their roles or those with similar professional standing within field and laboratory investigations (Rapp 1975; Gladfelter 1977; Goldberg 1988; 2008).

By their very nature, the essays written by those American scientists as well as those contained within the volume edited by Albarella are polemic, building upon both personal experience and anecdotal evidence. With these comments in mind, the aim of this article is to consider whether progress has been made and, if so, has the health of environmental archaeology improved and what challenges remain for the discipline.

In many ways, it could be suggested that a status quo has been maintained, given the continued influence of the two aforementioned drivers. Developer-funded research continues to thrive and pay the salaries of the majority of environmental archaeologists working in the profession, despite several reinventions of the UK planning framework and overall reductions in core funding for heritage, which has impacted on local government curatorial support and hence planning control (Institute of Historic Building Conservation 2013). Academics continue to be influenced by government research audits, including the RAE of 2008 and the subsequently repackaged Research Excellence Framework (REF) of 2014.

In addition to a consideration of the quality of research publications, REF 2014 included an assessment of 'Impact', defined by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (hefce) as 'an effect on, change or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment or quality of life, beyond academia' (archive link: http://www.hefce.ac.uk/rsrch/REFimpact/). Given what archaeologists do, the inclusion of Impact as part of REF submissions for 2014 (data collection period 2008-2013) should have had, and should continue to have, a positive effect not only on environmental archaeology but the entire discipline; the subject is capable of providing rich seams of data that illustrate accessible stories — what people ate, the conditions in which they lived, their health, their impact upon the landscape and how they responded to natural and societal adversity (climate change, extreme natural events, war, famine, diaspora). Furthermore, Impact has the potential to build partnerships between heritage managers, commercial organisations and academic departments, by developing research activities that contribute to the development of guidance, shape policy and engage in public discourse.

The establishment of such linkages between academic departments and commercial organisations is all the more important due to the closure in the last two decades of once significant university-based 'Field Archaeology Units' (FAUs), which often provided a direct interface between academics, the public, industry and local and national government heritage managers. A number of these organisations such as ARCUS (University of Sheffield), Trent and Peak Archaeology (University of Nottingham), Birmingham Archaeology (University of Birmingham) and GUARD Archaeology (Glasgow University) had strong environmental archaeology pedigrees, or at least employed staff capable of recognising the value of such palaeoenvironmental approaches to reconstructing the archaeological record. Interestingly, such closures were not foreseen in the papers edited by Albarella (2001) and, thankfully, not all UK universities have taken such a dim view of the value of FAUs and applied (commercial) activities within their ivory towers. However, even where they have been retained, the degree of synergy between academic departments and their respective FAUs is variable, with the latter often appearing to survive 'limpet-like' to the bottoms of these very large ships.

The rise of Citizen Science in the UK and growth in engagement of volunteer groups, in part underpinned by the grant schemes of the National Lottery Heritage Fund and other charitable groups such as the Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, can certainly provide momentum and funding vehicles for dovetailing the activities of academics and the wider profession, including the amateur community.

In addition to the two aforementioned drivers, research associated with climate change science has gained significant momentum within the last two decades (IPCC 2013), creating significant opportunities for environmental archaeologists to take centre stage in globally important debates. However, despite this opportunity, few environmental archaeologists (a term used here liberally) appear to have written contributions that directly engage in these discussions, including what our community can bring to the table in terms of knowledge as well as the impact on the heritage record (for exceptions, see Howard et al. 2008; Kincey et al. 2008; Murphy et al. 2009; Van de Noort 2011; 2013; Howard 2013; Sandweiss and Kelley 2012; Howard et al. 2015). In tandem with climate change debates, there has been a growing momentum within the scientific community to define this period of human-induced change as the Anthropocene. At the time of writing, the working group of the Sub-commission on Quaternary Stratigraphy is developing a proposal to be considered by the International Commission on Stratigraphy regarding the formal designation of the Anthropocene as a period of geological time. One possibility is that it should be formally designated as a geological Epoch and given comparable status with both the Pleistocene and Holocene, implying that the latter has ended. An alternative proposal is that the Anthropocene be considered at a lower hierarchical (age) level, which would make it a sub-division of the Holocene. As with engagement with climate change debates, environmental archaeologists have had significant opportunities to contribute to these discussions, particularly concerning the starting point and criteria for such designations; however, review of the mainstream literature suggests that this role has been left to the physical geography and geological communities (Zalasiewicz et al. 2011; Gale and Hoare 2012; Brown et al. 2013; Foulds et al. 2013; Cooper et al. 2018; Nichols and Gogineni 2018; Wagreich and Draganits 2018).

While this article could simply be based on a series of observations and anecdotes that provide views from either side of the divide regarding the health of environmental archaeology, the growth of metrics data associated with research publications collated by the major publishing houses and other organisations provides an opportunity to examine more objectively the health and status of the discipline. Elsevier's Scopus is one such platform; it is the world's largest abstract and citation database of peer-reviewed scientific literature and includes journals, books and conference proceedings, providing a comprehensive overview of research outputs in the fields of science, technology, medicine, social sciences, and the arts and humanities. While such platforms offer the potential to undertake serious statistical analysis of captured data, since the aim of this article is to provide a topical, horizon-scanning review, the data are used here in a much more limited way to tease out observations relevant to the debate.

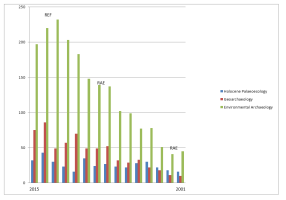

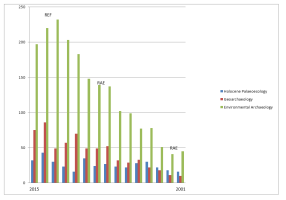

To capture metric evidence as part of this review, three key phases associated with environmental archaeology were selected and searched using the Scopus database. These phrases were: (1) Holocene Palaeoecology; (2) Geoarchaeology and; (3) Environmental Archaeology. It is accepted that readers of this article might not consider these three phrases as representative of the subject area and that another three phrases might yield different results. However, they were chosen after consideration of other possibilities; for example, a search using 'environmental reconstruction' yielded results that included numerous publications in hard rock geology journals and similar results were achieved using 'palaeoecology' in isolation. The Scopus search was across article titles, abstracts and keywords of papers published between 2001 and 2015 in the Physical Sciences (7200 titles) and Social Sciences and Humanities (5300 titles) subject areas.

| Year | Holocene Palaeoecology | Geoarchaeology | Environmental Archaeology |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 32 | 75 | 197 |

| 2014 | 43 | 86 | 220 |

| 2013 | 30 | 49 | 232 |

| 2012 | 23 | 57 | 203 |

| 2011 | 16 | 70 | 183 |

| 2010 | 35 | 49 | 148 |

| 2009 | 24 | 49 | 139 |

| 2008 | 27 | 52 | 137 |

| 2007 | 23 | 32 | 102 |

| 2006 | 22 | 29 | 99 |

| 2005 | 28 | 33 | 77 |

| 2004 | 30 | 22 | 78 |

| 2003 | 22 | 18 | 51 |

| 2002 | 18 | 11 | 41 |

| 2001 | 16 | 10 | 45 |

| Total | 389 | 642 | 1952 |

Analysis of the three phrases within the Scopus database (Figure 1; Table 1) demonstrates that 'Environmental Archaeology' is the most popular term, with a nearly 6-fold increase in its use from 2001 (45 papers) to 2013 (232 papers). There are notable jumps in publications using the term around 2012-13 and 2007-8, which coincide with the UK REF and RAE audit cycles respectively. Since 2013, there has been a steady decline in submissions linked to the phrase (down to 197 in 2015), although this probably reflects the publication cycle associated with REF with academics still working towards their next set of submissions.

Publications linked with the phrases 'Holocene Palaeoecology' and 'Geoarchaeology' are on a similar par between 2001 and 2004, albeit in relatively low numbers (30 and 22 in 2004 respectively; Table 1). However, post-2004, publications relating to 'Geoarchaeology' increased significantly to a high point in 2011 (70 publications) followed by a two-year decline until 2013 (49 publications), again followed by a rise and fall to 2015. While there does seem to be an increase in research outputs focused around Geoarchaeology close to the RAE in 2007-08, the same trend is not readily observable around 2013, but rather there is a decline in outputs. Post-2004, the phrase Holocene Palaeoecology continues on a par as described previously, albeit with slight increases and declines through time, though the level of use to the end of the census period (2015) is always below 50 publications, with no notable increases around RAE/REF cycles.

| Publication type | Holocene Palaeoecology | Geoarchaeology | Environmental Archaeology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Article | 363 (93%) | 522 (81%) | 1382 (71%) |

| Review | 12 | 31 | 162 (8%) |

| Conference paper | 9 | 22 | 149 (7%) |

| Editorial | 1 | 18 | 15 |

| Article in press | 1 | 18 | 16 |

| Book chapter | 0 | 17 | 105 (5%) |

| Erratum | 2 | 7 | 2 |

| Book | 0 | 6 | 71 |

| Conference review | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Short summary | 1 | 0 | 20 |

| Letter | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Note | 0 | 0 | 18 |

| Total | 389 | 642 | 1952 |

The majority of the key phrases are associated with publications in journal articles (Table 2) although there is a notable decline in the number of journal articles from Holocene Palaeoecology, through Geoarchaeology to Environmental Archaeology (93-81-71% respectively). This trend probably reflects the fact that the majority of papers using the term 'Holocene palaeoecology' are focused on long sedimentary archives in contexts such as wetlands and peat bogs whereas outputs linked to 'Environmental Archaeology' can be presented in a number of other ways; it is notable that a mixture of reviews, conference papers and book chapters account for around 20% of usage of the term 'Environmental Archaeology'.

| Holocene Palaeoecology | Geoarchaeology | Environmental Archaeology | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Holocene (82); IF 2.135 | Journal of Archaeological Science (93); IF 2.255 | Environmental Archaeology. The Journal of Human Palaeoecology (151) |

| 2 | Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, and Palaeoecology (39); IF 2.525 | Quaternary International (55); IF 2.067 | Journal of Archaeological Science (136); IF 2.255 |

| 3 | Journal of Biogeography (27); IF 3.997 | Geoarchaeology (44); IF 1.344 | Quaternary International (131); IF 2.067 |

| 4 | Journal of Quaternary Science (21);IF 2.553 | Geomorphology (19); 2.813 | The Holocene (55); IF 2.135 |

| 5 | Journal of Ecology (17); IF 6.180 | The Holocene (18); IF 2.135 | Science (39) |

In terms of the journal outlets for publication (Table 3), the keyword 'Environmental Archaeology' is most commonly associated with the Journal Environmental Archaeology (The Journal of Palaeoecology), followed relatively closely by Journal of Archaeological Science and Quaternary International. The fact that the journal Environmental Archaeology is the premier outlet will be of no surprise to the community since it is the house publication of the Association for Environmental Archaeology. While the third place of Quaternary International might surprise some readers, who perhaps consider it a more mainstream geographical publication, its prevalence reflects its popularity for collected, thematic papers, often emanating from conference sessions. The phrase 'Geoarchaeology' is most commonly cited in papers within Journal of Archaeological Science, which is over twice as popular as the third-placed publication (Geoarchaeology) and nearly twice as popular as the second-place publication (Quaternary International). In complete contrast, 'Holocene Palaeoecology' is not cited regularly in archaeologically focused journals, which probably reflects the majority of research associated with this phrase being carried out within Geography and Environmental Science departments.

| Holocene Palaeoecology | Geoarchaeology | Environmental Archaeology | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bergen | CNRS | UCL |

| 2 | Oxford | Durham | Oxford |

| 3 | Montpellier 2 (Sciences and Techniques) | CERGE | Durham |

| 4 | Lund | Univ. Arizona | Cambridge |

| 5 | Bern | Univ. Austin Texas | York |

It is interesting to note that the top five departments publishing material associated with the phrase 'Environmental Archaeology' are all within the UK (Table 4). In contrast, 'Geoarchaeology' citations are dominated by the USA and France, whereas 'Holocene Palaeoecology' is shared between the Nordic countries, France, Switzerland and the UK. Of course, these citations often reflect the concentrated outputs of prolific key individuals and research group leaders, who may or may not be practising environmental archaeologists. While it would be unfair and divisive in an article of this type to name such individuals, it is possible to identify them using Scopus; suffice to say that the term 'Holocene Palaeoecology' has one UK researcher in the top five authors, 'Geoarchaeology' has none and 'Environmental Archaeology' has two; notably, in 2016, none were paid-up members of the Association for Environmental Archaeology (Ruth Pelling, Membership Secretary, pers. comm.), although two of these might be considered to be practising environmental archaeologists.

Without doubt, this rudimentary examination of metrics data collected by Elsevier suggest that the term 'Environmental Archaeology' and others closely associated with it (especially 'Geoarchaeology') have thrived in the last 15 years, though the declining use of the former in the last few years is something that needs further investigation. However, in general, the discipline appears vibrant, though it is clear that the metrics data can be influenced by, and sensitive to, external drivers such as the RAE/REF. However, a key drawback of relying on metrics data generated by Scopus and the type of publications represented by it is that they are largely the preserve of environmental archaeologists working in the academic sector and/or postgraduate research students. Therefore, such data only tell a partial story.

Environmental archaeologists working within the commercial sector rarely have funded time allocated to publish their results in journals and the majority of this information ends up either in the 'grey literature' or, if published, buried within monographs beyond the reach of such metrics. In the UK, grey literature relating to environmental archaeology should be readily accessible via the Archaeology Data Service (ADS), in turn fed by project initiatives such as OASIS (Online Access to the Index of Archaeological Investigations). However, using the ARCHSEARCH option of the ADS to search for the three key phrases produced the following results: Environmental Archaeology, 921 records; Geoarchaeology, 518 records; Holocene Palaeoenvironments, 0 records. Using the ARCHIVES search option of ADS to search for key phrases yielded the following results: Environmental Archaeology, 111 resources (deposited 2001 to 2016); Geoarchaeology, 36 resources (2005-2013); Holocene Palaeoecology, 3 resources (2007-2010). For Environmental Archaeology and Geoarchaeology, there are notable spikes in deposition associated with the operation of the now defunct Aggregates Levy Sustainability Fund, in part administered by Historic England.

Given that the ARCHSEARCH option of the ADS indicates that it is 'an integrated online catalogue indexing over 1.3 million metadata records, including ADS collections and metadata harvested from UK historic environment inventories' this number of search returns is rather concerning. It suggests that environmental archaeologists and related disciplines working in the commercial sector either: (1) do not write reports; (2) write reports but do not deposit them directly with HERs and the ADS; or (3) assume that their reports will be deposited by others (i.e. as an appendix to a larger site report submitted by the lead archaeological project team). Since empirical evidence indicates that option 1 is demonstrably untrue, the explanation is clearly one of the latter two, though in reality most probably a combination of both. Either way, this low visibility of environmental data in the grey literature and lack of archiving should be of concern to the environmental archaeology community, since it has the potential to damage the credibility of the profession in the longer-term.

Certainly, within other parts of the archaeological community there is growing unease with the standards of reporting and quality of data in 'grey literature' despite the availability of existing standards, guidance and good practice advice (Cattermole 2017). Publication in peer-reviewed journals, many of which are moving towards the requirement that supplementary datasets are submitted (i.e. primary data), provides the opportunity for assessment of research quality by the wider community. Of course, if this problem of publication is to be overcome, it cannot simply be solved by environmental archaeologists alone. There is a need for project managers costing and designing commercial projects to bring specialists into discussions at the earliest stages of discussions so that appropriate outputs for knowledge transfer can be agreed. While it is acknowledged that County Archaeological Development Control Officers can find it difficult and outside the control of planning constraints to ask developers to pay for research, innovative solutions must be found to ensure data quality is maintained.

In his concluding remarks, Barker (2001) urged environmental archaeologists to drive research agendas and take centre stage in research projects. Publication outputs over the last two decades, particularly, though not exclusively, associated with alluvial environments suggest that environmental archaeologists have heeded this call (Bell 2013; Brunning 2013; Gearey et al. 2016; Jones 2017). However, in many ways, these publications build upon the solid foundations of earlier work, again often associated within alluvial settings; for example, the research at Langstone Harbour, Hampshire (Allen and Gardiner 2000).

While data provided by Scopus suggest that environmental archaeology is generally thriving and that its profile in peer-reviewed journals has clearly increased since 2001, these data only provide a partial picture of the health of the discipline. With the majority of environmental archaeology undertaken within the commercial sector, there is clearly a need to ensure that the data generated by such activity and predominantly published as grey literature are available for peer review and are of an appropriate standard for dissemination. Perhaps data quality and standards are the greatest challenge facing environmental archaeology rather than volume of outputs and I would argue for a greater focus on quality control, which in turn relies on a number of issues being addressed.

At a professional level, there is a need for networks, mentoring and guidance and this must not be left solely to individuals and/or research associations and must be enforced at a professional level by the industry itself. While not directly financially supported, the Archaeological Botanical Work Group and Charcoal and Wood Work Group provide excellent models for such initiatives. In 2001, the role of the relatively newly created Regional Science Advisors (of English Heritage) was mentioned (Hughes and Hammon 2001) and their importance has never been greater, especially as the gatekeepers of quality control.

While the Chartered Institute for Archaeology (CIfA) has a number of Special Interest Groups, for example Geophysics, Archives, Buildings, Forensic Archaeology, there is a notable absence for Environmental Archaeology, which comes under the auspices of the Finds group. This is a situation that should be remedied but probably requires more environmental archaeologists to join the CIfA and effect this change. With a larger group of environmental archaeologists within CIfA, this would enable Standards and Guidance notes to be produced for the discipline, which at present are notably absent.

However, equally as important is the need for environmental archaeology and science-based approaches to underpin UK archaeology programmes at an undergraduate level, rather than simply viewed as the 'nice to have' additions. A move away from a traditional reliance on period-based teaching might help achieve this, something that has long disappeared from allied disciplines such as Geography, thereby allowing more global 'big science' perspectives to be focused upon. It is essential that training excavations are designed where environmental and science-based archaeology is the raison d'être, rather than the departmental environmentalist being wheeled out for the day for their novelty value. At UK postgraduate level, once-distinct environmental postgraduate programmes have been diluted and subsumed within pathway degrees, again reducing the visibility of the discipline further.

The lack of formalised support from either the profession or organisations that would have traditionally led the way (i.e. universities), has led to organic initiatives developing, seeking to fill the gap in training, for example the 'Skills passport' developed by BAJR, which includes site formation processes as a core skill. While such initiatives are welcome, they must form part of a coherent package to push the discipline forward more generally, rather than simply filling the void.

Environmental archaeology has the potential to remain as a vibrant, distinct discipline producing globally useful data. However, if it is not careful, there is the potential for it to be consumed by the expanding horizons of Geography and Environmental Science, whose researchers are often generating and interrogating similar datasets but appear to be using them in a more active and innovative way to focus upon globally significant questions and debates. In the coming decade, it is essential that environmental archaeologists wake up to these global challenges and ensure high-quality datasets remain at the centre of their arguments.

Cite this as: Howard, A.J. 2019 Environmental Archaeology, Progress and Challenges, Internet Archaeology 53. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.53.1

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.