Cite this as: Bourke, E. 2020 Management of Isolated Islands: The example of Sceilg Mhichíl, Ireland, Internet Archaeology 54. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.54.14

The island of Skellig Michael (in Irish, Sceilg Mhichíl) lies 11.6km off the westernmost tip of the Iveragh peninsula, Co. Kerry, Ireland. The island is approximately 21.9 hectares in area. It is owned by the Minister for Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht on behalf of the Irish people, with the exception of the lower (working) lighthouse and its curtilage, the helipad and adjacent store. Skellig Michael is primarily managed as a National Monument in state ownership. The entire island was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1996 in recognition of the outstanding universal significance of its cultural landscape and the importance of its protection to the highest international standards. As well as the World Heritage Site, the rocks are home to gannets, puffins, storm petrels and many other birds. Owing to its ornithological importance, Skellig Michael is also designated as a Statutory Nature Reserve and a Special Protection Area, and is a proposed Natural Heritage Area. As an Atlantic island situated a significant distance from the mainland, the management of the site, in terms of protection, conservation and providing a guide service, comes with many unusual and unique challenges.

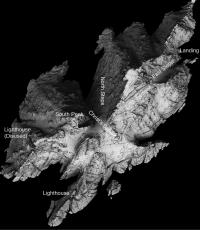

There are two separate elements to the monastic settlement on Skellig Michael: an extensive and well-preserved monastery constructed just below the top of a high, sloping rock platform on the east side of the island and a range of structures constructed on ledges high on the South Peak. Three long flights of steps lead up to the monastery from three different landing places. The monastery consists of an inner enclosure containing two oratories, a mortared church, seven beehive cells and the remains of a 'latrine', water cisterns, a cemetery, leachta (outdoor stone altars), crosses and cross-slabs. Two large terraces, referred to as the upper and lower monks' gardens, comprise the outer enclosure. High retaining walls support all the terracing upon which everything is constructed. On the other side of the island, rock-cut steps and ledges lead up to the structures on the South Peak. They comprise a series of platforms, traverses, enclosures and terraces daringly constructed on quarried ledges just below the peak. The oratory terrace still retains its original features: an oratory, altar, leacht, bench, water cisterns and a possible shrine. Crosses and a cross-slab have also been found on the South Peak.

Many commentators have taken an exaggerated view of the dangers of the island, but with no fresh water and gales, winter and summer, one thing that I came to realise in the 26 years that I've worked on the island was that any permanent, or semi-permanent settlement on the island required an adequately resourced shore base. So this is the story of the monks, lighthouse keepers and our own efforts to work on the island and the kind of resources each of us needed to continue to work and live there. We know a lot about how we are supported, and much of how the lighthouse keepers were supported, but learning something meaningful about how the monks were supported is a matter of working with the evidence that we have gleaned.

The main support for the modern-day workers on the island comes from the Office of Public Works, who have a local depot in Killarney, with a separate role for their Visitor Service Unit who manage the guide service on the island. All supplies come from Killarney and all the workmen and other tradesmen are based there. The huts have to be opened in the spring and maintenance carried out on them prior to work starting each season. The Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht has a role on archaeological policy and the National Parks and Wildlife Service deals with the wildlife. There are engineers on contract, and so too are safety and scaffolding experts.

The huts are quite comfortable, though small, and all water, gas and other supplies have to be brought to the island. All material brought to the island and not consumed is returned to the mainland. The crew work five days a week, twelve hours a day, but the guides stay on for two weeks at a time. The guides have an extremely busy job when tourists arrive, but the visitors are mostly gone by 4pm, which gives them time to see a different view of the island. Sometimes the sun is shining but frequently there is a fierce swell; in some way they are more like the former lighthouse keepers, with very busy periods, as well as lots of down-time.

In 1880 the Office of Public Work took the monastic remains into guardianship and commenced a project for the repair of collapsed structures. However, by the late 1970s, the condition of the site was such that there were considerable structural problems requiring attention. Some were very serious in scale with potentially grave consequences, while others were more localised. The ongoing conservation works programme at the early medieval monastic site on Skellig Michael commenced in 1978 and has continued each summer season since then. The first season's work was in response to the collapse of a section of retaining wall to the west of St Michael's Church within the monastery, and shortly thereafter work focused on the repair of the south steps, the main access route to the monastery. Survey work began at this time and the first archaeological intervention took place in 1980, with excavations proper commencing in 1986 and continuing almost every season until 2010. The scope of the archaeological work on Skellig Michael is primarily determined by the conservation needs. This was deemed the most appropriate strategy given the limited area actually available for excavation on this precipitous island and the intact nature of the structures, in the monastery in particular, which have been left undisturbed.

Over the years, the archaeological work has ranged from monitoring and supervision to full excavation and, because the scope of the archaeological work was determined by and large by the conservation works programme, investigations were focused on the monastery and associated structures and the South Peak. In 2010, survey and conservation works commenced on the lighthouse road, and currently a programme of conservation works is ongoing at the old (disused) lighthouse.

Our interventions have varied between large-scale operations in the monastery, the South Peak and, more recently, the lighthouse structures, to small-scale emergency excavations where interventions had to be made to solve a small-scale problem. In the monastery, the problem was often the fact that there had been many previous collapses of drystone masonry and that resulting interventions were frequently based on multiple previous failures. Indeed, some of our difficulties came from late 19th century repairs, when the site was originally vested into State Care.

Detailed pre-works surveys commenced in the late 1970s and have continued throughout the duration of the works programme. Both measured surveys and photographic surveys are carried out, and, since 1994, the works have been recorded professionally on film. Plans, sectional profiles and elevations are recorded at various scales during excavation; following conservation, all structures are again recorded in detail. Surveying on Skellig Michael presents many challenges, not least of which is the vertiginous nature of the terrain, with its attendant health and safety requirements. Plane table surveys have been used extensively, and in 1982 a photogrammetric survey (1:1000) of the island was commissioned, which provided detailed contours and allowed the individual monastic structures to be correctly located on the island. As survey and recording of the South Peak structures progressed, however, it has become clear that the level of locational detail on the contour map was insufficient for accurate recording in this precipitous terrain. Consequently, a three-dimensional geometric survey of the island has been carried out in 2007, using aerial LiDAR (Light Detection And Ranging).

The featuring of the Skelligs in the most recent Star Wars films has dramatically increased the public interest in this site. If it was located anywhere else, the increased footfall brought by its new-found fame would certainly have an impact. Thankfully, its Atlantic location and a narrow visitor season that itself is so weather dependent, means that the island has natural restrictions that limit its visitor capacity. While new technological advances will certainly help us record and monitor the impact of natural forces on the archaeological monuments perched on the edge of the Atlantic, its location will continue to present logistical challenges in terms of protecting and presenting the site to the public.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.