Cite this as: Cooper, C., Hadley, D., Empsall, J. and Wallace, J. 2021 Digital Heritage and Public Engagement: reflections on the challenges of co-production, Internet Archaeology 56. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.56.18

UK Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) are now active in encouraging public engagement activities, with considerable funding available for academics to present their research to the public or to co-produce beneficial changes to local communities. In this article we reflect on both the benefits of these sorts of projects and also the challenges that can emerge in developing them. We specifically review a selection of case studies in which digital technologies have been used in public engagement, including two recent examples of our own work at Park Hill flats in Sheffield, UK, in which academic researchers worked with a community group (Park Hill Residents' Association) and the creative agency HumanVR, also based there. We argue that what works well in public engagement activities requires critical analysis, as do the hurdles that may emerge in co-production, particularly with respect to being able to involve different groups in the development of projects, and responding to what they may want from interactions with academic researchers.

Public engagement by HEIs has been increasingly encouraged by the requirement of the UK research councils to demonstrate the significance and value of their research beyond the HEI sector (e.g. Bond and Paterson 2005). The last 20 years have seen the proliferation of bespoke funding streams, such as the Higher Education Innovation Fund, which 'supports and incentivises providers to work with business, public and third-sector organisations community bodies and the wider public, to exchange knowledge and increase the economic and societal benefit from their work' (Research England 2020). Public engagement activities have not, however, gone unchallenged, and are increasingly being subject to sharp critique. For example, there have been criticisms of the 'impact agenda' as part of a broader disquiet about what is widely perceived as the commodification of Higher Education (Molesworth et al. 2011; McGettigan 2013). Concern has also been expressed about academic research being tied to the economic benefit of society, and accordingly shaped by the need to demonstrate societal benefit to secure funding or as part of audit, specifically the Research Excellence Framework (REF), which places considerable weight on research impact (Watermeyer 2016). Some of the most effective engagement activities may, in fact, be far removed from the model of the REF impact case study (e.g. Ryall et al. 2017, 346) or 'government-approved conceptions of impact that posit a crude cause-effect relationship between research and its influence on individuals and communities outside the academic realm' (Harte and Hazley 2021, 55–6). Nonetheless, in a research environment valorising REF impact, UK-based academics may find themselves having to account for the 'value' of their public-facing activities if they are not quantifiable in REF terms.

Some experienced exponents of public engagement have observed that the very terminology used for public engagement activities typically, and inappropriately, posits the academic as the expert and the public merely as the recipient of knowledge. At the same time, however, academics may find themselves having to navigate public perceptions that are 'inaccurate' and community partners who value other aspects of the engagement over and above 'knowledge' (Ryall et al. 2017, 339–40). Others have opposed this sort of response, arguing that public engagement should not be celebrating 'everything that is popular, bottom-up and local', and urging academics to provoke people 'instead of flattering them'; '[p]rovocation, engagement and education, rather than flattery and collaboration, should become the new key concepts guiding our relationship with society, or at least with those sectors of society that have remained beyond our radar' (González-Ruibal et al. 2018, 509, 511, 513).

Nonetheless, even with these recognised shortcomings, and differences of scholarly opinion about best practice, public engagement activities are now well established in UK HEIs and widely regarded as a positive endeavour, albeit 'without significant reflection beyond an ill-defined sense that involving the community in our activities is a worthwhile thing to do' (Bowden 2021, 79). Researchers may, in practice, be dissuaded from critical reflection by potential negative funding implications of revealing anything other than the successes of their public-facing work, and perhaps from an unwillingness to be self-critical about their own actions. Yet there are uncomfortable issues to be addressed, not least because, in practice, public engagement is typically harnessed to the interests of academic research, public bodies or funders. There needs to be acknowledgement of the shortcomings of the approaches taken, often driven by the emphasis of the funders on co-production, including the nature of the power relations involved in collaborations between academic researchers and members of the public. There are also ethical issues to be addressed with respect to extracting in-kind contributions from members of the public and community groups, as is often required for funding applications to be successful (Fredheim 2018; Richardson 2018); this is effectively an externalisation of labour costs to participants. Even collaborations that endeavour to be acts of genuine co-production find that the collaboration is dictated by university notions of value, including the need to publish and measure 'impact' (Bowden 2021, 86-88). As Bowden (2021, 87) has observed, this changed the nature of interactions with the public who could now 'no longer simply enjoy things but had to be "transformed" by them, and the extent of that transformation had to be recorded and quantified'.

Digital technologies are increasingly being tested as an innovative means with which HEIs can engage external stakeholders, supported by dedicated funding streams. For example, the Immersive Experiences programme of 2017 was developed jointly by the Arts & Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), 'to explore the new technology-enabled, multi-sensory, narrative, interpretative, and performance experiences that will drive future creative and commercial value' through interdisciplinary collaboration 'and inter-sector working between researchers, creative practitioners, and businesses' (AHRC and EPSRC 2017, 1). Thirty-two projects were funded, under the strapline 'Memory, Place and Performance', exploring the use of immersive experiences in museums and galleries, libraries and archives, outdoor heritage settings, dance, and music, and many involved community groups or explored the benefits of such technologies for communities (Creative Economy Programme 2017). The outcomes of two of these projects reveal contrasting experiences of co-production.

One of the authors of this paper (Hadley) was PI on an Immersive Experiences project exploring the use of digital technologies in the context of heritage-led urban regeneration (Leach et al. 2018). The case study was Sheffield Castle (South Yorkshire), demolished during the 17th-century English Civil War; its location now stands derelict, and is the subject of a long-running regeneration initiative led by the City Council in collaboration with local businesses, university researchers and members of a local community heritage group, the Friends of Sheffield Castle (Moreland and Hadley 2020a, xiii–xxi). A digital model of the medieval castle was created, using Maxon Cinema 4D and Unity game engine software, in collaboration with HumanVR, who were brought into the project for their technical expertise. This model was then transformed into an Augmented Reality experience for use with an iPad and employed in exhibitions, alongside an architect's wooden scale model of the part of the city where the castle once stood. This was highly successful in engaging the public and local government in discussion about future developments on this site and how its heritage might be central to this (Moreland and Hadley 2020a, 336–38; 2020b; 2020c). While the idea of a digital platform emerged at the suggestion of the academics in the light of the funding call, the community group, who were lobbying for the heritage of the site to inform regeneration, were integral to writing the funding application, decision making during development, user-testing and delivery of the app. While immersive technologies were being explored by the academic team for their wider applicability in the urban regeneration space, much of the success of the project lay in its focus on a specific case study with a recognised local need.

In contrast, reflection on the findings of another Immersive Experiences project highlighted disquiet about the capacity of digital technologies to engage the public (Swords et al. 2021). This project focused on making heritage 'usable', by utilising immersive technologies to take it outside of the museum for public consumption. However, a series of practical and philosophical issues emerged from the stakeholder consultation, which included representatives of the heritage sector, technology and computer science organisations, and architecture and planning specialists. Such stakeholder consultation is commonplace but rarely afforded critical analysis. The HEI team at Northumbria University identified significant disciplinary differences of perspective and priority: 'throughout all the phases of our project it was clear actors were approaching the design of heritage-led immersive experiences from very different ontological and epistemological perspectives reflective of disciplinary and practice orientations' (Swords et al. 2021, 191). Technology specialists focused on finding appropriate technological solutions for immersing visitors in the past, which sometimes 'betrayed a lack of understanding of the complexities involved in understanding and using heritage'. In contrast, heritage specialists wanted to explore 'the plural, contested and partial nature of heritage', albeit with a recognition that coherent and attractive narratives were required for visitors and that there was 'potential for non-digital technologies to immerse people in the past' (Swords et al. 2021, 8, 192-193). The short-term nature of funding, the relatively high staff turnover in the heritage sector and concerns about sustainability were also highlighted as prohibitive to development of immersive experiences for heritage dissemination; this revealed that there is still some way to go before digital access to heritage is widely regarded as essential. Indeed, another of the Immersive Experiences projects led by Prof. Will Bowden (University of Nottingham) decided against involvement of community partners to address the challenges of location-based Augmented Reality in a rural landscape. Despite this project emerging from a long-running collaboration with a local community archaeology group exploring the site of the Roman town of Venta Icenorum at Caistor (Norfolk), the decision was influenced by a previous project to develop a GPS enabled location-based tour, which had garnered only limited interest from the group (Bowden pers. comm.).

In 2019, two of the authors (Cooper and Hadley) reviewed the potential of using digital technologies within the context of heritage-led urban regeneration, as well as the impediments, courtesy of a grant from the AHRC. Alongside a literature review, we interviewed a series of academics and community groups about their experiences of working on heritage-led urban regeneration, seeking examples of good practice in co-production of digital assets and understanding about why certain collaborations had not achieved their stated aims. This revealed concerns about the tendency for short-term consultation processes, and pump-priming for prototype activities, rather than sustained relationships and long-lasting project outputs. It was evident that true co-production is rare, certainly at the outset of project development, as academic partners, alert to the requirements of diverse funding schemes, frequently need to determine the shape of projects prior to involving community groups.

Many projects, with only short-term funding, have focused on development of web-based delivery or creation of apps that require community groups to have their own equipment. As Richardson and Dixon (2017, section 5) highlight, however, 'social and political issues ... are inherent within the power structures of the use of and possession of access to digital technologies'. Community groups (and individuals) do not routinely have access to these technologies and the situation is exacerbated by funding rarely being available to meet required equipment costs. These projects typically have a very short lifespan and once the funding has ended, community groups are left unable to update or even continue to use what has been created. For example, a collaboration between the Friends of Northampton Castle and Northampton University's VR Centre produced a VR experience in 2015, but interviews with the creator (Thomas Kivits-Murray, Pixel Creative Technologies) and the charity highlighted that, while it had been an exciting collaboration, on-going maintenance of the app had ended as funding dried up and staff moved on to other projects. The consequences of funding only digital heritage prototypes or short-term projects is just starting to become apparent as digital assets begin to fail and we can observe their lack of sustainability. This may not have been anticipated by, or explained to, community partners in advance, not least because academics and funding bodies do not always seem to have addressed this.

We also discovered that some projects had ended when academics moved university, and community partnerships that had been forged no longer met the strategic interests of their new organisation. This situation can also be exacerbated by the terms of the REF, as the underpinning research for impact case studies cannot be transferred between universities if staff move institution (REF 2020). Furthermore, universities protect partnerships that might underpin impact case studies, given the financial implications of the REF, which is a disincentive to keeping researchers involved in established public engagement activities if they move universities. One academic to whom we spoke, who wished to remain anonymous, highlighted their disappointment at being cut out of a long-term community engagement project following a change of University, which they believed was driven by REF considerations. In an experience common to others we consulted, they also spoke of their frustration at losing access to a range of digital assets produced at their former institution, and they felt that no consideration appears to have been given by former collaborators to the impact on community groups of their departure from the project. This raises some ethical concerns, and Bowden (2021, 86) has written of the need for academics to be clear with community collaborators about the fact that some of the activities they will be undertaking are being driven by the requirements of the funder: 'from the start I was quite explicit about this with the group members, insisting that accurate records were kept of volunteer hours, because such data would be important for funding applications'.

A shortcoming in the development of digital applications and experiences for public engagement initiatives is that community groups typically lack the skillset required to maintain these applications in the long term, and are often not briefed on such issues when they are approached to co-produce these experiences. Solutions to these issues have seen interventions that focus around time-limited installations to respond to specific events or producing prototypes. Sometimes community groups are brought in effectively as part of the evaluation phase, rather than from the start; for example, Dr Laura Harrison (pers. comm.), a Creative Economy Engagement Fellow at the University of Glasgow, produced an immersive audio tour at Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh, and used community consultation as part of the later evaluation and testing, rather than opting for co-production. However, Dr Richard Brook (pers. comm.) at Manchester Metropolitan University, who led another of the Immersive Experiences projects, separated the technological side of project development from the community engagement, which was focused on provision of research materials for the VR experience created (https://www.thelifeofbuildings.org.uk).

During this research we (Cooper and Hadley) were introduced to the Residents' Association at Park Hill flats in Sheffield by Nick Bax, Creative Director of HumanVR, with whom one of us (Hadley) had worked on a previous public engagement project (see section 3). We wanted to consult with a community group that was living through an urban regeneration and active community building process (see section 5), but had not yet had the opportunity to experience digital technologies in this context. We interviewed four members of this group, allowing them to explore a Google Cardboard Virtual Reality (VR) experience, a tablet based Augmented Reality (AR) model, and an interactive website (Figure 1). They expressed a clear interest in using such platforms on site to present and explore aspects of the history and plans for the future of the flats:

Sue: [I] Didn't consider using digital approaches, but think it's a great idea. It would be great to show the development of the site and the building itself.

Mick: [It] Would be interesting to look out over the city from Park Hill in the 1960s to see the city 'in full pelt'. [There are] Lots of photos of Park Hill but not many looking out from Park Hill.

Amy: It would really resonate with people. I think it [Park Hill] is the perfect place to do something like this.

Anne: [I] Think technology and creativity (e.g. plays and art) go hand in hand in representing Park Hill.

Given this expression of interest, we subsequently worked with the Residents' Association and HumanVR to secure funding to develop together digital resources for the site. We will now discuss the two projects that emerged, and reflect on the successes of the projects but also on the difficulties we encountered, shortcomings in the approaches we initially intended, and the extent to which we resolved them.

Park Hill flats are a well-known landmark in Sheffield, opening as social housing in the early 1960s, and now undergoing regeneration after a long period of decline (Figure 2). Before discussing the ensuing outputs, the history and reputation of the estate will be considered, as this is critical to understanding the trajectory of our two projects.

Park Hill is one of the most divisive buildings in the country. This brutalist structure was built between 1957-1961, designed by architects Jack Lynn and Ivor Smith, under the supervision of Sheffield City Architect J. Lewis Womersley (Saint 1996). The primary vision was to re-house a community from the Victorian slums in the Park area of the city, dubbed 'Little Chicago' given its notoriety for crime and gangs (Harwood 2003, 52). The post-war period saw a need for radical housing re-design in Sheffield, with Park Hill representing an innovative solution, informed by post-war utopian developments throughout Europe, such as Le Corbusier's Unité d'habitation in Marseilles (France) (Empsall 2020, 25-33). A key philosophy for the Park Hill architects was to foster a sense of community within the design, most evident in the 10ft wide street decks dubbed 'streets in the sky' (Figure 3), and the communal spaces, including a shopping district (The Pavement), community centre, and public houses (Figure 4).

They were hailed as the 'City's "Super" Flats of the Future' (Sheffield Telegraph 1955), with the decks viewed as 'the real social backbone of social communication … [where] kids play, mums natter, teenagers smooch and squabble, dads hash over union affairs and the pools' (Banham 1962, 134). However, contrasting this optimism were predictions that Park Hill would fail, with architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner (1967, 466) claiming in 1967 that the estate would be a 'slum in half a century or less'. In 1979, the Sheffield newspaper The Star published a damning letter entitled 'A cry of despair from a prisoner of Park Hill', in which an anonymous resident wrote of 'a life sentence of 20 years, without remission' in a community characterised by 'prejudice, racism, drug addiction, theft, violence, obscenity, prostitution and corruption'. Articulation of such views contributed to Park Hill's 'spiral of decline' (Bacon 1982, 303). The estate was also afflicted by wider developments, with the 'Right to Buy' scheme for council houses, introduced by Margaret Thatcher's Conservative government in 1980, encouraging a decreased desire for council flats, the decline of Sheffield's steel industry, and ensuing rise in unemployment, with 40,000 jobs lost from Sheffield's population of 200,000 between 1979 and 1989 (Hanley 2017, 117).

With its growing reputation as a 'problem estate', Park Hill saw a period of dramatic decline from the late 1980s. However, the estate was saved from calls for demolition by its Grade II* listing by English Heritage in 1998 (English Heritage 1998; List no. 1246881), which acclaimed the 'international importance' of 'Sheffield's flagship' in public housing. After planning permission was granted for redevelopment, urban regeneration specialists Urban Splash took on the development of the flats in 2008 and the building work is ongoing. Urban Splash (2020) are aiming to create 'a neighbourhood with a real mixed tenure'. When our research commenced in 2019 there were 260 homes, of which 10% are social housing, 25% affordable housing and the remainder for leaseholders, as well business spaces, a nursery and a café.

In working with members of the Park Hill community on two digital heritage projects in 2019 and 2020, we were mindful of the contested history of the estate and its diverse stakeholders, and we felt it important to draw on a broad range of experience and views. The current residents communicate through a private Facebook group run by the Residents' Association, while former residents, many of whom lived at Park Hill in its early years, keep in touch through a different private Facebook group. In contrast, former residents that lived on the estate during the period of decline in the 1980s and 1990s do not appear to have a strong voice, if any, within the known community stakeholder groups. Conversations with residents highlighted the nearby Park Centre library as a hub of the local community in lieu of a community space on site. Urban Splash are another stakeholder, whose remit is to promote the estate as a vibrant and prosperous place to live, and they work closely with Great Places Housing Group, which is responsible for day-to-day maintenance of the estate (Empsall 2020, 66-70). Businesses based at Park Hill include the South Street cafe, whose premises we used for conducting interviews, and HumanVR, whose staff provided both technical support and also insight as members of the Park Hill community.

In developing our projects, we were informed by Laurajane Smith's (2006, 299) discussion of the dangers of the Authorised Heritage Discourse (AHD), which prioritises 'elite class experiences, and reinforces ideas of innate cultural value tied to time depth, monumentality, expert knowledge and aesthetics'. We were also mindful of work critical of public engagement initiatives, which have a tendency to be top-down in their implementation (Crooke 2010, 18), with the perspectives of professionals often driving projects as they have more power and control in the relationship with community groups (Perkin 2010, 118-19). This way of viewing community groups derives from the AHD, and the way in which heritage is articulated within the sector, with the expert-centric focus having 'rendered communities, as much as their heritage, as subject to management and preservation' (Waterton and Smith 2010, 11; Empsall 2020, 15-16). These issues are magnified at Park Hill, which has transitioned from council housing estate to gentrified apartments, now catering to a more middle-class demographic, and it was important to ensure that the heritage that was articulated in our projects was not shaped by an expert-centric approach. Park Hill has strong roots in the intangible, through the stories, identities and experiences of its residents, both past and present, who do not necessarily have a conventional understanding of heritage, but are intrinsically connected to what is significant about Park Hill. Within this context, we felt an added responsibility to consult diverse community stakeholders, and give a voice to those that are often excluded from community-based initiatives within the AHD.

The first of our projects at Park Hill was funded by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) through their scheme Enhancing Place Based Partnerships, which sought to engage under-represented communities and places with research and innovation. The funded projects worked with communities from the lowest quartile on the Index of Multiple Deprivation to shape research and innovation relevant to their lives and local areas (UKRI 2019). We applied jointly with the Residents' Association for this, with the very idea for the project emerging from interviews we had undertaken with some of its members as part of our earlier consultation exercise about the potential for digital technologies to be employed in urban regeneration contexts. We then co-created a digital aid to enhance tours of Park Hill flats led by its members, which they use both to generate a modest income and to manage the raft of visitors to Park Hill, including regional school pupils, university students, and groups interested in architecture or photography.

Initial conversations with the Residents' Association by one of the authors (Wallace) revealed their wish to create a smartphone-based app to be downloaded by visitors prior to their visit, but this presented us with an immediate challenge of managing expectations. This type of delivery assumes all visitors would have a device, and in the time available, it would not be possible to create an app for both Apple and Android products and to choose one would have excluded those visitors who used the other from accessing the download. There would also be potential problems if visitors did not download the app in advance and then could not access the internet on site, or lacked sufficient power or space on their device. The Residents' Association would also struggle to update any such app without significant training or subsequent additional funding, and there were potential copyright issues over images with dissemination of the app online. Furthermore, there was also the potential that groups would download the app and lead their own tours around the site, which was already a concern that residents had, who felt that visitors were sometimes regarding the site as a museum leaving them feeling that they were living in 'a goldfish bowl' as one resident put it to us (Empsall 2020, 106). Ironically, while we had set out not to fall into the trap of the AHD, it could be argued that our community partners could be seen to be doing so. However, this does not take account of the tension between Park Hill as a heritage site and Park Hill as a residence (for similar issues, see the discussion by May (2020) of fell shepherding in the Lake District as heritage participation focused on the future of an intangible heritage, which is somewhat at odds with the endangerment and protection narrative of a World Heritage bid). The nature of the regeneration was a factor in this, as what had previously been publicly accessible 'streets in the sky' were now effectively privatised by the installation of gates and doors and residents wanted to retain some degree of privacy in the face of visitors.

After discussing the issues with the smartphone idea, and with the approval of the Residents' Association, the decision was, therefore, taken to use a tablet to deliver the app, to negate the issues we had jointly identified. Furthermore, unlike other funding streams, the UKRI grant was flexible and permitted purchase of sufficient tablets to provision average-sized groups at a ratio of one tablet for three visitors (at the time of writing, social distancing as part of Covid-19 precautions, was still in place and as a result this may no longer be an appropriate ratio). This provision of technology made the project more sustainable and more widely accessible to visitor participation; ownership of a high-end smartphone would not be needed to use the app.

Sustainability was a key consideration when creating the app, with allowance for the fast-changing nature of technology and software, but easily updatable by the Residents' Association. It also had to be suitable for use by most age demographics, from secondary school age upwards, given the range of potential visitors for which it needed to cater. After consideration of both internet based web apps, and tablet based offline apps, PowerPoint was chosen as the program in which to run the app, as it was free to download onto the tablet, and members of the Residents' Association were already familiar with the software, which would enable future updates. Six Samsung Galaxy Tab A 2019 tablets were purchased for the project, with a screen size of 10.1", each with their own protective silicone case. PowerPoint formats have largely been backward compatible and therefore are a reliably stable file format. The tablets, on the other hand, have a limited life expectancy, even with fairly minimal use; Samsung cover up to 3 years although most tablets should last 5 years. In addition to providing the Residents' Association with the tablets and training them to use the app, we provided some guidance notes for ongoing updates and maintenance at the end of the funded project.

Through conversations with the Residents' Association about the format of their tours, the decision was made to create a location-based app that could be referred to at specific locations during the tour. From the home screen the tour guide can navigate the visitors through the app as they move around Park Hill (Figure 5), and each location provides visitors with archival images and film (Figure 6 and Figure 7). The choice of content was largely driven by availability of relevant images from the city archives, and access to a short film from the 1960s provided by Urban Splash. Through collaboration with the Residents' Association, images and film clips were chosen to reflect the history of Park Hill, not shying away from controversial elements, but equally mindful of the need not to control the narrative and to leave the decisions about the shaping of the tours to the Residents' Association guides. We were also alert to the fact that the site is undergoing regeneration and being promoted as an attractive place to live, but also subject to local controversy (e.g. Byrnes 2016). While we had our own views on this, and about the controversy around the 'gentrification' of the estate (Empsall 2020, 58-62), and the exploitation of working-class heritage for middle-class designer living (e.g. Byrnes 2016), we felt the nature of our collaboration with the community meant that we needed to avoid commenting on the material as best we could and leave them to navigate this debate in whatever manner they wished.

The capabilities of the PowerPoint software enabled us to create a long form PowerPoint presentation, with site locations accessed through a home page (Figure 5). The home page was designed to be intuitive to use, with in-app buttons outlined to the right of the screen. Information and question buttons were included throughout the presentation to provide added context to the images, and to encourage critical thought concerning the, often controversial, history of Park Hill. Pages with videos were designed to be easy to use, and the videos can be replayed if needed. Animations were used to create smooth transitions between pages, and to create a professional finish. The app focuses on eight locations at Park Hill, in those areas already regenerated, providing information, photographs and film footage about the flats, shops, social spaces, children's spaces, the decks, the relationship of Park Hill to the city, and the building and regeneration of the estate. These locations are key points on the resident-led tours, within those parts of the estate that have been regenerated; other parts of the flats are currently inaccessible while building work continues.

During the early stages of development we were able to trial the app with a specialist photography group touring Park Hill. This was a useful exercise in working out what subtle changes were needed in the appearance of the app (e.g. moving the date graphics for better visibility, and making buttons larger), and to flag user experience issues. The reception the app received was very positive, with the group expressing their appreciation for the appearance of the app as a whole, and for the media used within it. They were particularly impressed with the film footage, which depicts Park Hill shortly after it first welcomed residents in the early 1960s.

We presented the final product to the Residents' Association accompanied by necessary accessories and information to run and maintain the app. The reaction was very positive. One member of the Residents' Association, who regularly leads tours, provided the following feedback:

We run a good number of tours at Park Hill every year. We get architects from all over the world, modernists, there is a lot of local interest also. We also get visits from schools – we are on the syllabus for GCSE geography as an example of urban regeneration. So the decision was made to design an app which we could use on these tours. The idea is that as you walk the streets at each location the app will show you images and clips of interest especially of life as it was, but also of the insides of the flats as they are – very useful since we cannot always provide flats to view. Anyway it is a lovely app to use and the footage that has been sourced is also lovely.

Video: Stories in the Sky: digital placemaking by Josie Wallace [film]. This video has audio.

We also created an accompanying website about the project and its goals, and with information about the history of Park Hill, as an educational resource for schools, and accompanied by a short film about the project (see Video above). These resources have been useful in providing context to their case studies, particularly for those living rurally who might not have visited a metropolis or left their hometown before, and especially in the light of the restrictions ensuing from Covid-19. One teacher who used the site reported:

Due to Covid 19, we haven't been able to complete our annual fieldwork at Park Hill Flats; however through the use of these resources, we have been able to let students gain a deeper understanding of why Park Hill Flats needed to be regenerated and the changes this caused. We are excited to try out the interactive app when we will be able to resume our GCSE fieldwork as the 3-D technology will allow the students to fully grasp the changes to the site, almost bringing the history to life for them (Catriona Scoular, Outwood Academy, Foxhills, Scunthorpe, Lincolnshire).

The pandemic prevented further user testing of the app but the overall experience of the project was of a successful collaboration creating a useful digital aid to the resident-led tours. The only notable challenge was the need both to explain clearly the merits and shortcomings of potential platforms and software and to manage expectations of what could be achieved with the time and budget available.

Our second project created a prototype Virtual Reality storytelling experience, which could also be used as part of the resident-led tours of the building. This was a Masters by Research project funded by XR Stories, an AHRC-funded Creative Cluster focused on storytelling and the screen industries in Yorkshire and the Humber (Empsall 2020). The project endeavoured to capture stories of Park Hill life from those connected to the estate. Through working closely with community stakeholders on the content, we aspired to amplify a diverse range of voices on Park Hill's history and its intangible heritage.

With our commitment to community engagement, we began by making contact with the Facebook groups of both current and former residents and visiting the Park Hill library community hub. In addition to the four interviews undertaken by Cooper in 2019, which had led us to pursue this collaboration, we secured four more stakeholder interviews: with two current residents, a former resident and a staff member from Great Places Social Housing (Empsall 2020, 66-70, appendix 2). While the eight interviews provided invaluable insights into community needs and interests, we had, however, hoped for more responses, and became concerned whether we were effectively engaging with community stakeholders. However, we discovered that the published results of other projects based at the estate had noted similar problems with securing interviews. Bell (2011, 163) has coined the phrase 'Park Hill fatigue', for this disinclination among those living in, or associated with, Park Hill to participate in any new research projects. Interviews have been a part of the estate's history since its inception, when the social worker Joan Demers was tasked with recording and encouraging the development of new community bonds, and there have been multiple radio and TV interviews throughout the estate's history. Bell (2011, 145) abandoned plans to interview residents for her doctoral thesis on conservation and regeneration, as she felt that they had been 'consulted to death'. Chiles et al. (2019, 122) reached a similar conclusion following their efforts at co-production with members of the Park Hill community (Empsall 2020, 70-1).

Reflecting on these previous studies, and on our own experiences of finding only limited interest in contributing to co-producing the VR experience, we adapted our methodology. We turned, instead, to the wealth of information about Park Hill available in existing oral testimonies of residents, which has often been undervalued by projects in favour of new interviews. There is different, but equally important, value in drawing on existing testimonies to inform digital heritage outputs and working with community stakeholders as part of the evaluation and user testing process instead. Archived oral testimonies are a largely untapped resource for developing diachronic reflections on heritage (Gallwey 2013, 38). While there are acknowledged limitations with reuse of such data, especially concerning the lack of context subsequent users possess about the data collection methods (Bornat 2003), we felt that such concerns did not outweigh the potential for supplementing our interviews with a wider range of community input. Accordingly, we supplemented our own interviews with recordings of resident testimonies available in Sheffield Archives, and others recorded by Urban Splash in 2019; this was in the lead up to the performance at Sheffield's Crucible theatre of a musical about Park Hill, Standing at the Sky's Edge (Kalia 2019), and the recordings were used in the foyer to inform theatre-goers about the history of the estate. Although we were able to incorporate resident voices, our aspirations for a co-produced output felt compromised as we were now in full control of the decision-making process for the VR product for a site with a complex range of heritages, and were working with the community in a different way than we had planned.

During interviews undertaken as part of the initial AHRC-funded project the residents had been particularly drawn to the use of VR, with one stating that it would 'definitely be useful for the heritage trails … [and] Lots of photos of Park Hill that could be used in the VR to highlight where things were', while another highlighted that 'It would really resonate with people. I think it is the perfect place to do something like this'. Given this response, and the one-year time frame of an MRes, it was decided to focus on producing a 3D, VR experience. 'Stories in the Sky VR' utilised 3D modelling software 3DS Max to create a series of virtual environments depicting the evolution of Park Hill's 'streets in the sky'. While visualisations of this type have been critiqued for their lack of human presence (Tost 2007), the time frame limited what we could achieve, which did not permit inclusion of human avatars. The rendered 3D models and oral testimonies were edited with Adobe Premiere Pro and exported as a 360° video. It is just over 3 minutes long, and presents a series of vignettes presenting a chronological perspective, relating Park Hill life to the material culture of the place (see Video). Decisions about what to include were informed by availability of oral testimonies by Park Hill residents.

Video

: The virtual reality model of Park Hill Flats by Joseph Empsall [film]

360° video - view the video from every angle by swiping or moving your device as it plays. This video has audio.

The first section presents Park Hill as an iconic building, with the strong sense of community that emerged from the resident interviews. The street deck appears clean and polished, featuring a notice board displaying newspaper articles on Park Hill's construction and a milk float, which was a recurring image in the visualisation of Park Hill in its early years (Figure 8) (Empsall 2020, 77-9). A model of The Link pub was also included (Figure 9), and oral testimonies are employed to describe the use of such amenities in this early period. One former resident of Park Hill states: 'They say it's a cliché that it's a village in the sky, down here you had absolutely everything you could want'. We included The Link because of the perceived benefit of more such communal spaces in the regenerated estate mentioned in several of the recent oral testimonies (Empsall 2020, 78).

The second section of the VR model focuses upon the estate's changing reputation. It is purposefully darker than the first to mirror the deterioration of the estate's reputation, and also because of the lack of resident voices on this period in the oral testimonies, leaving us reliant on external perceptions of the estate (Empsall 2020, 79-81). For example, Pevsner's 1967 claim that the estate would be a 'slum in half a century or less' is visualised as graffiti, to encourage the viewer to think critically about the damaging implications of wider perceptions (Figure 10). This decision was informed by a former resident's testimony, presenting a contrasting perspective to that of the authority figure of Pevsner: 'I have often seen videos where Park Hill is described as a slum ... all I can remember were the great people that were around'. Yet this was unquestionably a difficult time for the estate's residents, and the remainder of this section considers the 1979 newspaper letter from 'a prisoner of Park Hill', and the impact of political developments, such as the decline of the steel industry and the Right to Buy scheme. During interviews undertaken by Cooper in 2019, Mick from the Residents' Association reflected that

The steel strikes have been wiped out of history [...] and all memory of the strikes is gone even though it was such a big event. This and other examples of activism have been purposefully forgotten.

He suggested that including this period would help highlight this difficult and forgotten past.

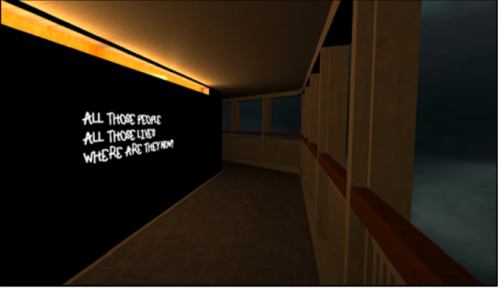

The final section of the model focuses on the regeneration of the estate under Urban Splash, and features the redeveloped street deck, accompanied by oral testimonies from current residents (Figure 11) (Empsall 2020, 81-3). One states: 'one of my favourite things to do is to lay on my back and look out at the clouds'. From the many interviews undertaken throughout the building's history, one element that connected them, no matter when a resident lived at Park Hill, was the experience of looking out from the decks. Stories in the Sky VR concludes by considering Park Hill's community today. A current resident discusses a Creative Writing Group stating: 'the best thing about it is we all got to meet people off the flats ... people off Norfolk Park, Manor, and from Park Library ... we are all integrating, and it's about the whole community, not just us'. The model of the street deck transitions to the night sky, and centres upon neon signage, incorporating a line from the 1942 film The Man Who Came to Dinner reused by the band The Smiths in 1986, which was written in graffiti at Park Hill prior to regeneration: 'All those people, all those lives, where are they now?' (Figure 12). This prompts the viewer to think critically about the history of the site, and highlights how far the heritage of the estate is interconnected with wider developments.

Our intention to host an exhibition at Park Hill, to showcase the VR model and gather user feedback, was prohibited by the impact of COVID-19. Instead, the VR was posted to YouTube as a 360° video, and user feedback questionnaires were disseminated, asking how effective the immersive experience was in showcasing Park Hill's diverse stories, experiences, and history (Empsall 2020, 83-88, appendix 3). We were already aware we might struggle to elicit a response owing to wider issues with community engagement at Park Hill discussed above (see section 7.2), although this exercise generated a stronger response.

Feedback indicated that such projects are useful to the Park Hill community, suggesting that they appreciate public interest and research into the estate. The positive comments included that the video was 'short but quite powerful', 'the mix of clips from news/media and real people is effective and interesting', 'it gave you a feel of it all', and it was 'very good and clear'. However, there was also a sense that it would have been more effective if the video was longer: 'It was too short. Would have been good to see the people who were speaking. Fascinating subject. Would have loved much more'. Being able to hear the voices of current and former residents was appreciated: 'The most effective item was having multiple recorded testimonies linked to the “timeline” of the building through the decades', while another liked 'the different voices and intertwining with social history.' A former resident appreciated the format, stating 'the video with its 360° appearance was good to watch, if only this was available at the time of my youth', with another liking that it felt 'modern.' Two participants liked The Link pub scene, as it represented something they had not seen before.

Some respondents commented that their experience of the estate was only partially represented in the video, noting that 'there is far more info that could be added by present and former residents', and 'there are so many things that could be said'. Multiple respondents thought that the video would have benefited from a variety of shots including a visualisation of inside the flats, past and present: 'that way maybe the flat can have other items showing the time transition/periods ... to get the more human side associated with the testimonials'. We acknowledge that much more could be said and shown, but a succession of projects have needed to balance encouraging participation with avoidance of overwhelming the community with the constant stream of requests for community support. A current resident felt that the 360° video 'is perpetuating the myth that the "community spirit" of Park Hill has survived':

Park Hill does not have a great community spirit. It has a Facebook group and a few individuals who have tried to develop something that is about slightly more than geographic proximity. But the majority of residents are, for the vast majority of the time, indifferent.

The indifference described may have been one of the barriers to securing interviews, along with the broader issue of what has been dubbed the Park Hill fatigue phenomenon (Bell 2011). That being said, we felt there was value in producing an experience of this kind and telling a story with lots of stakeholders in a new way that builds on a different type of co-production. Working with the vocal minority of current residents willing to engage could be seen as problematic and narrow, but we felt the use of existing oral testimonies in developing this product created space for representation of a wider range of voices, as well as spearheading alternative forms of public engagement and digital approaches to storytelling in heritage contexts.

The project provided some important lessons about the challenges of attempts at community co-production when the research questions are driven more by academic concerns and issues than by an extant community need. This case study was funded through XR Stories, which has a mission to 'champion a new future for digital creativity', bringing together universities and industry partners, like HumanVR. Our project included a third key stakeholder in 'new forms of interactive and immersive storytelling' – the audience and their stories. There are ample archival materials available, and new interviews are not necessary, which prompts reflection on the best ways to incorporate community input into development of digital storytelling experiences in the future.

Waterton and Smith (2010, 12) have discussed the 'cuddly nature' of community engagement work, as well as the role of heritage to be seen to be doing 'good.' They argue this works to ensure that the problems within community engagement are little discussed. Co-production is generally seen as a laudable way to approach heritage-led community projects, and often required by funders, yet how this is implemented may not be straightforward, and the difficulties encountered are rarely reflected upon afterwards. For this to work, there has to be a positive response from community stakeholders, and a willingness to contribute and participate. It is tempting to critique a lack of engagement from a community as a result of such expert-led projects, but wider encouragement of co-production does not necessarily proceed as planned. Some have gone so far as to criticise what they see as an 'an idealisation of community' by archaeologists, advocating that they need to take a more critical stance, and not simply valorise the views of people who were 'supposed to be the bottom-up producers of non-authorised heritage' (González-Ruibal et al. 2018, 510). In a UK HEI context, however, co-production is embedded in, and a requirement of, many funding schemes (including those discussed here), leaving little room for adoption of this perspective; this presents a challenge on which archaeologists need to reflect.

In this article we have reflected on two related projects at Park Hill flats in Sheffield that used digital technologies to present the history and heritage of the site. In both cases we set out to co-produce the output with the local community but the outcomes were different. In the first project the resource, a tablet-based app, was co-produced with the Residents' Association to meet a defined need for the resident-led tours. In the second, more creative, project, there was a shift of focus and we attempted to introduce the community to the wider potential of digital technologies to articulate intangible heritage, at a place where the tangible elements of the site are well known, to spark discussion, and to reflect the views of a diversity of stakeholders. The co-production involved the community as subject as much as collaborator, and this is, perhaps, where some of our ensuing challenges lay. We initially encountered little interest in discussing it with us, although feedback garnered more interest in engaging with the project and with seeing a wider range of Park Hill stories and experiences incorporated in our model. It was only after we had created the digital output, co-producing with the community on the basis of previously recorded testimony, that we were able to spark enthusiasm and engagement. We hypothesise that perhaps the digital nature of the project, dictated by the funding stream, meant that the community struggled to envisage what was being created and therefore were reticent to engage. The diverse communities of Park Hill have a strong understanding of their heritage, but we also discovered that there are numerous competing stakeholder interests in the presentation of the history, present and future of Park Hill, and not everyone is interested in sharing their stories. While capturing these narratives seemed initially to be a valuable undertaking it became clear that many of the issues are too raw and controversial for inclusion in a heritage experience that will retain stakeholder interest. Furthermore, we were confronted with the challenges of co-production if your collaborators are also partly the subject of study. The findings of our community engagement suggest a need to step back from trying to undertake community consultation at Park Hill. This is not to say that stakeholders should not be supported by external organisations; however (after Bell 2011) the reality at Park Hill is that stakeholders are 'fatigued' by the number of engagements with their heritage and their lives. Future attempts at co-production need to be sensitive to this. A major learning experience for us concerned the challenges and sensitivities surrounding working at places where heritage and home overlap. As May (2020) highlights, we fell into focusing on Park Hill as a heritage site; presenting the site's past and the threat to that heritage being lost. When we stepped back and considered Park Hill as a home and lived in space we began to think about it as a place of the present and future with specific needs, including privacy.

Digital technologies are the latest means by which HEIs are seeking to engage with the public, but it is becoming clear that there are significant impediments to undertaking this successfully. The short-term nature of the funding, the difficulties of maintaining outputs and managing community expectation of what can be achieved in the time, and with the funding, available. Projects often prioritise new consultation activities, and co-production with communities, over making use of archival materials. Sometimes this is driven by funders requiring co-production, leading academics to seek out community partners, but it can also be due to a lack of awareness of the potential of archival sources and a fetishisation of new interviews. The wider public are not always as interested in digital technologies, or as familiar with their potential, as academic researchers anticipate. The inclusion of a 'co-produced' approach would be valuable to other heritage-led community projects, but the context of Park Hill made this difficult to achieve. Nonetheless, the findings of our work are of value in showing ways to draw out community voices through archival materials; indeed, we would suggest that the constant driver of funders to support academics to engage with the public is actively encouraging new dialogue, sometimes with communities that then turn out to be uninterested or suspicious of such approaches, at the expense of making good use of existing community engagement materials.

Funding for the two projects based at Park Hill flats was awarded by UKRI through their scheme Enhancing Place Based Partnerships, and XR Stories, an AHRC-funded Creative Cluster focused on storytelling and the screen industries in Yorkshire and the Humber. The UKRI funding permitted the appointment of Josie Wallace as Project Officer, while the XR Stories funding supported a Masters by Research thesis undertaken by Joseph Empsall. Both of these projects were supervised by Catriona Cooper and Dawn Hadley, with technical advice provided by Dan Fleetwood and Nick Bax of HumanVR. The Immersive Experiences project based on Sheffield Castle was funded by the AHRC and EPSRC (grant no. AH/R009392/1), and subsequent research on heritage-led urban regeneration was funded by the AHRC (grant no. AH/S010580/1), and conducted in collaboration with Dr Steve Maddock (University of Sheffield), who kindly provided feedback on this article. Matt Leach, who was RA on the former project, helped with providing digital technologies for the interviews at Park Hill Flats in 2019 conducted by Catriona Cooper, and Julian D. Richards provided access to headsets used in the VikingVR project, a collaboration between the University of York and Yorkshire Museum. We are grateful to Sue, Mick, Amy and Ann from Park Hill Residents Association for agreeing to be interviewed in 2019. We appreciate the time taken by Jon Swords (Memoryscapes), Laura Harrison (Framing Heritage through Play), Tom Kivits-Murray (Pixel Creative Technologies), Richard Brook (The Life of Buildings), Stella Jackson (Grimsby Heritage Action Zone) and the team at Calvium for talking to us about their research, as well as others who preferred their responses to remain anonymous. We are also grateful to Prof. Will Bowden (University of Nottingham) for discussing his public engagement work with us. We are grateful to Picture Sheffield for permission to reproduce an image from their collections, and to Surriya Falconer at Urban Splash for providing access to a film from the early 1960s for use in the app developed for the resident-led tours. We are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for helpful feedback and additional bibliographical suggestions. We would also like to thank members of the Park Hill Flats Residents' Association, especially Amy Littlewood and Dave Watkins, for their assistance and support with the two projects discussed in this article. Funding for this publication was provided by the York Impact Accelerator Fund.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.