Cite this as: Monckton, L. 2021 Public Benefit as Community Wellbeing in Archaeology, Internet Archaeology 57. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.57.12

Historic England is the UK Government's advisor to the historic environment in England. It carries out a variety of statutory functions, such as maintaining a list of 'Buildings at Risk', advising Government on buildings suitable for designating on the statutory list (that is the National Heritage List for England) and providing advice to Local Authorities within the planning system. It has a central and regional structure, managing strategic approaches, research, grant giving and guidance between them. Regional offices work closely with local partners to support regeneration and public engagement within a variety of programmes.

As an organisation, Historic England aims to be an inspiration to, and a resource for, the sector in multiple areas relating to the protection of the historic environment. The concept of how we perceive the historic environment has evolved since the 1950s, when it was primarily about the issue of monuments in care, to late 20th-century questions about the 'power of place' and 'public value'. The public value of archaeology is not a new concept in the UK but the scope of its definition and potential is expanding. This is seen not least in the EAC's own work on defining what public value comprises (see Sloane, this issue). Within the EAC proposed framework for public value in archaeology there are eight areas:

Wellbeing as a therapeutic intervention through the practice of archaeology exists in small pockets in the UK, where it has focused on meeting a particular need. However, the idea of wellbeing as a policy objective at a more strategic level has been gaining ground across the arts, cultural heritage and archaeological spectrum. In terms of the historic environment generally the debate has been rumbling for much of this century. In 2005, Tessa Jowell, then the Secretary of State for Culture stated:

'we need a new language to describe the importance of the historic environment…[we need to] increase diversity in both audiences and the workforce, to capture and present evidence of the value of heritage, to contribute to the national debate on identity and Britishness, to create public engagement and to widen the sense of ownership of the historic and built environment.'

Since then the language has gradually changed and now, I would argue, 'wellbeing' is part of a way of articulating what this collective of value and impact actually does, and could, look like.

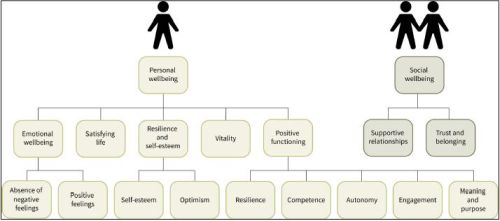

Wellbeing might usefully be thought about in two key ways:

Expanding this further one might articulate wellbeing as an individual issue (how does one feel things are going), a collective issue (how well is a community or area doing), and a population level issue (how well are policies affecting change for the country as a whole). Each is focused on what difference we can make and all are relevant to how we approach wellbeing. Each is related to how one feels and how one is affected by the social, economic and environmental context of daily life.

While wellbeing (in the sense of improving lives whatever their starting point) is itself a worthy aim, arguably the real goal is to address wellbeing inequalities as a means to provide better chances and opportunities to all in society. Wellbeing is a mechanism through which we can address issues of social impact, health inequality, productivity, diversity and local identity.

Why we should do this, beyond the inherent moral imperative of making lives better in our communities, is a simple matter of pragmatism. In addition to delivering wellbeing outcomes, looking at our work, at all levels, through a 'wellbeing lens' will enable us to deliver to the public value frameworks we work to, thus establishing organisational relevance and therefore resilience. The concept of 'public value' has a particular meaning to UK public bodies as a result of the 2017 Barber Report, which called for a more results-based culture in the public sector and requires that, in order to demonstrate the value to the public of a publicly funded body, there is a responsibility to show what positive difference the investment has made.

Our core purpose at Historic England is now identified as being 'to improve people's lives by protecting and championing the historic environment'. Wellbeing is both a tool to help deliver this improvement and an outcome that demonstrates the potential values of the historic environment to society. In summary, therefore, wellbeing is essentially a way of thinking about our social impact and demonstrating it helps provide evidence of our 'public value' in the context of the Barber report. I believe our role should be to create change through our impact and therefore the tenor of this document is about active participation and process as much as outputs; success depends upon a combination of ideological focus, outlook, and risk taking as much as the, still important, traditional delivery focus on skills, resources and opportunities. As will be seen below, wellbeing is as much about a way of doing something as it is about what we do.

The main part of this article will consider the following three areas. They will be necessarily brief but I hope they will provide some information and food for thought on how development-led archaeology and wellbeing can inter-relate and how this can sit within a broader strategic framework.

In my experience there often appears a slight tension between the idea of strategic thinking and the drive to just 'do' projects. On the one hand, while preparing a strategy, one is often asked, what difference will it make on the ground or a feeling of just wanting to get on with things; one the other hand, working in practice may well lead to interrogation regarding why something is being done in a certain way and a search for a rationale behind decision-making.

This article concentrates on the possibilities for the strategic focus. Its main purpose is to show how the development of a strategy is a necessary process in defining direction and purpose. My hope is that by suggesting a strategic framework for considering wellbeing as a lens through which to see our work, it will show three things: how to conceptualise archaeology and its constituent practical parts as a force to improve wellbeing; how to explain to others what we mean when we talk about it; and provide a model for how we might report and answer questions about what difference we make to society at a professional, organisational or project level.

Although I have referred to some basic principles above, it is worth alluding to the meaning of wellbeing in a little more detail. In the 1940s, the World Health Organisation defined Health as 'a state of complete physical, mental and social wellbeing and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity'. (Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19-22 June, 1946; signed on 22 July 1946 by the representatives of 61 States: Official Records of the World Health Organization, no. 2, p. 100) and entered into force on 7 April 1948.)

The UK government defined wellbeing in 2010 as 'a positive physical, social and mental state; it is not just the absence of pain, discomfort and incapacity. It requires that basic needs are met, that individuals have a sense of purpose, and that they feel able to achieve important personal goals and participate in society. It is enhanced by conditions that include supportive personal relationships, strong and inclusive communities, good health, financial and personal security, rewarding employment, and a healthy and attractive environment' (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs 2010).

The latter, in particular, emphasises the two key aspects of wellbeing mentioned above – that is, the factors that contribute towards one's potential for wellbeing – henceforth known as the social determinants of wellbeing, and an individual's own cognitive and affective evaluations of his or her life – henceforth known as subjective wellbeing.

The Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council of New South Wales – Australia, states that:

'Health is not just the physical wellbeing of an individual but also the social emotional and cultural wellbeing of the whole community, in which each individual is able to achieve their full potential as a human being, thereby bringing about the total wellbeing of their community.'

This particular definition suggests an approach that is more community-orientated than many and links the individual and the community together; at the same time it alludes directly to a concept of 'cultural wellbeing'. Assuming this more holistic and culturally sensitive definition is a result of the needs of the Aboriginal communities to have their cultural life maintained as an integral part of their wellbeing, it offers a useful perspective on how cultural life as an entity is inter-related into collective wellbeing in a way that is potentially useful for cultural organisations that are looking to see how the value of a community's cultural inheritance and engagement with that inheritance can be expressed.

The historic environment is a powerful part of that cultural inheritance. Wellbeing is personal and subjective, but also universally relevant. Heritage is a profession and a concept based on values (arguably what matters to society); wellbeing likewise is values-focused (what matters to an individual). In theory, therefore, they should be compatible.

The What Works Centre for Wellbeing provides a useful summary of the nature of wellbeing and its challenges:

'Wellbeing encompasses the environmental factors that affect us, and the experiences we have throughout our lives. These can fall into traditional policy areas of economy, health, education and so on. But wellbeing also crucially recognises the aspects of our lives that we determine ourselves: through our own capabilities as individuals; how we feel about ourselves; the quality of the relationships that we have with other people; and our sense of purpose.'

These psychological needs are an important part of what makes us human, along with our ability to feel positive and negative emotions. It matters how often, and for how long, we experience positive emotions – such as pleasure and a sense of purpose – or potentially negative emotions, like anxiety.

If we accept that some aspects of wellbeing are subjective, we can better understand the interactions and trade-offs between different experiences. We can also take into account the longer-term effects and the different importance of these things to different people. Part of the value of wellbeing as a concept is that wherever you are and whatever your cultural background or personal circumstances, people intuitively understand the value of happiness and wellbeing. But this universality that adapts to so many different contexts and perspectives can sometimes make it difficult to share a common understanding of what exactly wellbeing is.

This description by the What Works Centre for Wellbeing encapsulates a key challenge in thinking about wellbeing: wellbeing is complex, multi-faceted, ever-changing and highly personal. As a result there is the potential for multiple expressions of wellbeing at any one time, which raises challenges within organisational frameworks that tend to focus on fixed plans, clear impact and predicted outputs. This can lead to organisational anxiety about how to identify actions and outputs that are robust and meaningful in a seemingly endlessly complex environment.

The first thing to say in response to this is simply that having a strategy at least explains to others why you are doing what you are and provides a basis through which others can respond to or add to your own understanding of the issues. For example, we will be talking to Mental Health charities and other parts of the health sector about our strategy to do a reality-check to ensure we understand the issues we are trying to influence. The second response is that, despite its inherent complexity, there are some established means of considering what wellbeing looks like for society, providing a statistically validated set of approaches and a set of invaluable base-line data.

In the UK, the most useful is that provided by the Office of National Statistics, which was requested to create wellbeing indicators for society in 2010. They stated that:

'Wellbeing, put simply, is about "how we are doing" as individuals, communities and as a nation and how sustainable this is for the future. We define wellbeing as having 10 broad dimensions which have been shown to matter most to people in the UK as identified through a national debate. The dimensions are: the natural environment, personal well-being, our relationships, health, what we do, where we live, personal finance, the economy, education and skills and governance. Personal wellbeing is a particularly important dimension which we define as how satisfied we are with our lives, our sense that what we do in life is worthwhile, our day to day emotional experiences (happiness and anxiety) and our wider mental wellbeing.'

There are two key reasons why this definition is important. One is that it characterises the two dimensions of wellbeing highlighted earlier: that is, social determinants along with the sense of personal assessment of how well we are doing (SWB). The second is that the ONS provides us with base-line data for assessing wellbeing impact and changes in national wellbeing that could be used as benchmark information across the country and its localities, and give a clearer picture of where different priorities might exist.

This strategy therefore considers our role, and that of the historic environment, in both the social determinants of wellbeing and subjective wellbeing. Wellbeing might be seen as a way to pull together these factors and enable the complex ecosystem of their interdependence to be articulated and considered. In addition to this we need to consider, in my view, the issue of how contested a field heritage and archaeology actually is and its relevance for the wellbeing agenda.

The rhetoric found in the policy field tends to associate the work of cultural institutions and activity as being inherently positive for wellbeing outcomes. This belies an unwritten assumption that all heritage or cultural engagement, archaeological or otherwise, is 'good for you'. The heritage sector is not one cohesive entity – and in particular the process of archaeology and its results and outcomes are often highly contested. While this may have been focused recently in the public eye in many parts of Europe on the issue of statues and either colonial or political pasts associated with oppression, it is something that has the potential to emerge in multiple ways. Starting from an assumption that heritage is essentially good for you risks a lack of awareness of the potential for difficulty. Acknowledging the difficulty means risks associated with projects are at least considered. Many organisations are highly risk-averse and it raises the question whether considering wellbeing and heritage together demands some element of risk-taking to carve out successful outcomes and learn from our mistakes.

Having said all of this, this notion of 'wellbeing' is easily presented as a new imperative. Of course, people have been doing brilliant work with archaeology and communities for years. Often the benefits of those projects were aimed at one of the suggested eight public benefits of archaeology listed above – most commonly that of education – whereas now we want to be able to articulate the values associated with archaeology and heritage in more complex ways. The question is not simply, what did someone learn from access to an excavation or participation in part of an archaeological process, but what difference did it make to them and their lives. This difference then has the potential to affect their subjective wellbeing and the social determinants of health and wellbeing.

In the UK, while there are scoping surveys of archaeological and heritage-based projects that aim to look at their wellbeing outcomes (see Heritage Scoping Review; Evaluating social prescribing), the most common issues raised include questions over comparability and validity of evaluation, ability to collate evidence, quality of evaluation and lack of availability of results. Knowing that you achieved what you set out to do is one thing, but being able to show that to others in a way that is comparable to a broader context is now needed to make your case. Essentially there is a dichotomy between grass-roots community work and the desire for networks, alignment, resources and consistent measurement.

Historic England is developing a heritage and wellbeing strategy that will provide a framework within which to consider how we and the sector can deliver wellbeing outcomes. Set against the background of complexity above, the strategy is needed to attempt to establish a framework through which we can operate, be seen to operate and report against. Therefore its purpose is partly to map our existing activities against, and identify gaps in, our potential for delivering positive wellbeing outcomes. It is to enable us to show others what we are doing; it is purposefully straightforward, aims simply to capture the kinds of opportunities and to be scaled up or down as required. That is, it is hoped that it can be applied to any project, programme, organisational or sector context.

As an historic environment organisation, we are well-used to thinking about any kind of 'heritage asset' as something that may benefit from protection (designating, interpretation, conservation, presenting and maintaining). It can also include a responsive approach, reacting more specifically to deterioration or change, whether caused by neglect, development or the ravages of time and climate. These ways of thinking are core to much of our activity and the planning of our programmes of intervention with regard to all kinds of places.

The wellbeing strategy will propose that we consider this in combination with an approach that focuses as much on people as on place. For some this feels like a shift away from the so-called core function of heritage bodies, as the so-called 'intrinsic' qualities of our cultural heritage are enough and there is no need to 'instrumentalise' our work in this way. In response to this view, I would argue that the need to demonstrate the benefits of archaeology and heritage have never been greater. Several small countries have started to redefine their approach to public policy through creating a wellbeing strategy against which to measure success. New Zealand (and here), Scotland and Iceland are at the forefront of this movement and are founder members of the Wellbeing Economy Governments (WEGo). Wales introduced the Wellbeing of Future Generations Act in 2015 and even the House of Lords in the UK has pressed for a similar approach in England, although the government has not yet taken this on board. The way we talk about value and culture has changed and continues to change. We hope the heritage and wellbeing strategy will provide some structure to how we consider our response to that change. At the time of writing, it is being suggested the strategy has 3 key aims (Figure 1):

All of which will contribute towards a vision that heritage, whether through archaeology, interpretation, regeneration, research and so on will support flourishing communities in healthy places.

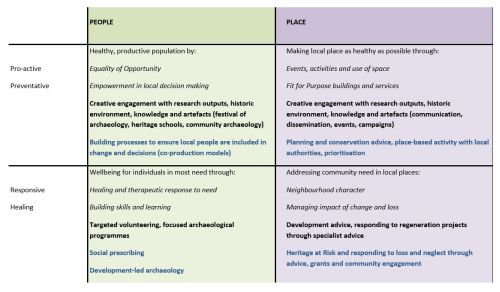

The health sector has long spoken about prevention and cure as their two-pronged approach to health. While I would not advocate the use of the word 'cure' in relation to heritage assets, or indeed any work with communities the sector engages with, it does arguably mirror the sort of proactive response that we as a heritage sector work within. If married together, then the relationship of our work and the health sector unites to form a focus on the interaction between places and people. This is expressed by the simple 2x 2 matrix (Figure 2), where we are suggesting each domain (from A-D) provides a sense of the primary driver for some form of wellbeing work. This approach can be used, as here, to apply to an organisational portfolio, or to an archaeological programme or strategy. The use of logic models is more common in the public sector than it used to be and if one preferred that style of presentation one could simply see this as articulating the headings of 'objectives' (text in normal or a colour) and 'goals' (italic text) in such a format.

In terms of what this means for us as an organisation at Historic England and in order to explain how this translates, Figure 3 includes indications of the kinds of activities that might fall within each category. In some we might be leading on pilots and projects and for others we might be providing advice and guidance. These are indicative only and the full strategy includes more complex active SWOT analyses and mapping exercises.

What is immediately telling is that the suggested activities in the people/healing box are ones that we currently do not undertake. The most comprehensive gap in our portfolio at the time of writing is work that focuses on a particular person or community-based need. And yet, there is considerable research to suggest that the bigger wellbeing benefits can be gained for those who are most deprived or affected by disadvantage in some way.

One way to think about how this applies to organisational practice is to consider a hierarchy of intervention, depending on what the primary goal is, for example:

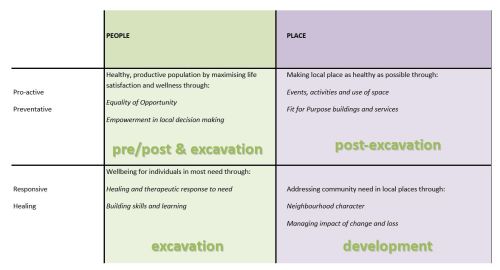

Taking development-led archaeology as an example – if one considered how this overlays onto the archaeological process at a simple level one might ascribe which of the four 'domains' and associated goals relates best to which part of the archaeological process. For an example see Figure 4.

Whether or not projects set out to achieve what might be captured under the term wellbeing improvements or outcomes, there are examples of archaeological project work that has shown its potential. One of these was carried out in the 1980s: the University of Arizona archaeologists launched Project Origins, working with autistic and disabled young adults both in an archaeological context and related laboratory work.

'Participants identified and collected surface artefacts; dug; pushed wheelbarrows; screened sediments to expose cultural materials; operated systems to float organics out of sediments for analysis; and cleaned, sorted, and labelled'. In this project it was observed that there were benefits for the assistants as they learned, shared, and otherwise connected to places, objects, one another, and the collected materials'

In a development-led context, an example can be found in the Port Angeles dock, Washington, where, in 2003, construction was underway. A poor archaeological assessment meant that there was no expectation of finding remains but almost 300 burials were found from an indigenous cemetery. Locals from the indigenous community associated with the land on which their ancestral burials were found were involved in the archaeological process that followed. As reported by Mapes (2009, 166), 'One of the best things about the discovery of the site, tribal elders say, was that it gave tribal youth the chance to discover their culture with their own heart and hands'. There was a strong connection for many between the link with history and identity and the relationship to wellbeing that that can bring, which was created not from the work taking place but from the community being involved in the work directly. Despite this, the process was not all about wellbeing – the discovery of burials where bones had been used to fill pipes was very traumatic and contested for some. More information on this can be found in an article from Current Anthropology (Schaepe et al. 2017, 502) in which the authors summarise their findings on this and other projects as follows:

'Archaeology has untapped potential to elicit and confirm connections among people, places, objects, knowledges, ancestries, ecosystems, and worldviews. Such interconnections endow individuals and communities with identities, relationships, and orientations that are foundational for health and well-being. In particular, archaeology practiced as place-focused research can counteract cultural stress, a pernicious effect of colonialism that is pervasive among indigenous peoples worldwide.'

In the UK, there are a number of archaeological initiatives that relate to the wellbeing of veterans. They take the form of research excavations rather than being development-led but their now established format means they provide a basis for understanding the potential benefits of the archaeological process when tailored in this way. One of the best known of these is Operation Nightingale, a military initiative developed to use archaeology as a means of aiding the recovery of service personnel injured in recent conflicts, particularly in Afghanistan. A recent analysis of the programme found that 'Soldiers reported a mean of 13%–38% improvement across the self-reported domains' (Nimenko and Simpson 2013, 296). The results demonstrate decreases in the severity of the symptoms of depression and anxiety and of feelings of isolation, along with an increase in mental wellbeing and in sense of value. There are poignant and persuasive stories of individuals involved in the process, including a wounded-in-service veteran, who lost a leg due to an improvised explosive device, excavating the foot and boot of a British soldier from the 1917 Battle of Bullecourt. As before, however, it is a pre-requisite of any therapeutic work such as this to be set within a support framework for dealing with trauma and with specialists in the effects and symptoms of Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome (PTSD) for example. Just because the potential outcomes are good does not mean it is straightforward to implement (see Everill et al. 2020).

Considering the suggested framework for reviewing gaps identified above in the therapeutically-led work at Historic England, we have been doing three things – collectively these will help build the evidence base for archaeology and wellbeing through specific application. One is to look at our existing work in the area of our Heritage at Risk projects and highlight the ways in which we have already been delivering public value so we can see how to build on this through reflective practice. We have also been investigating the potential to engage with particular wellbeing and health agendas in the UK such as 'social prescribing'. Thirdly, we have initiated research into the feasibility and, once the social distancing implications of the COVID-19 pandemic have eased, the practical application of new approaches. One such study is focused on what archaeology and heritage interventions could do for younger people who are vulnerable in some way.

Although a draft at the time of writing, the aim is that our wellbeing strategic approach will have four priority wellbeing areas: two focused on particular social challenges at the current time: mental health and loneliness (and of course exacerbated by the circumstances surrounding the pandemic) and two highlighting two parts of society where we feel we could make a significant difference: young people and older adults.

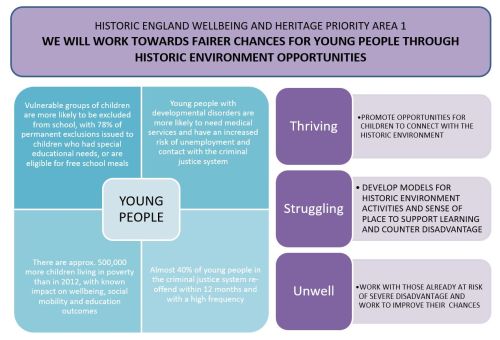

In thinking about young people, we are suggesting that for the current time we consider three ways to consider where we might target resources and these are set out in Figure 5, providing categories of engagement that are likely to require different approaches and a structure against which we can report what we have explored or produced. Figure 5 shows these three categories and these are duplicated for all of the four wellbeing priority areas of loneliness, mental health, ageing and young people. Some programmes of work may focus on a general level of population engagement targeted at children and minors: development-led archaeology has many examples of this in terms of education and engagement with the fact that an excavation is taking place through site visits and other initiatives. However, there is a question about where we can make the most difference. Figure 5 also summarises some of the issues that young people face and which commonly puts them at a disadvantage in society.

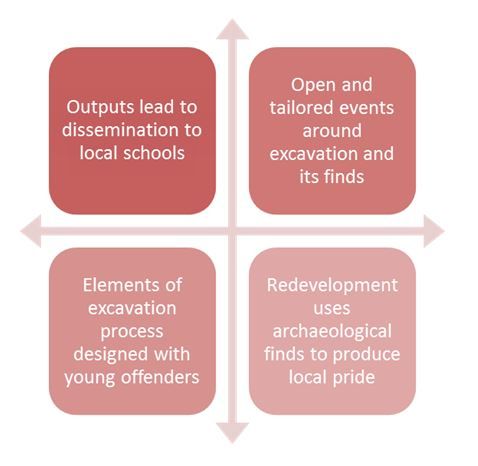

Figure 6 shows the kinds of ways the four domains can help direct the kinds of interventions in an archaeological development-led process if focusing on young people as an example.

There are clear links between developmental disorders and entering the criminal justice system, clear links between living in poverty and low wellbeing, and challenges for those in the criminal justice system escaping it. No one project can hope to address any of these issues in their entirety, but we can aim to work in these areas to explore ways in which archaeology can contribute towards making a difference. As a result, we have commissioned Wessex Archaeology to conduct a feasibility study on what working with young offenders or those working in the criminal justice system might look like. It will be dependent, from the very start, on understanding the needs of the organisations that already serve these young people and on the needs of the young people themselves. It will need to take into account the safeguarding required and the particular opportunities that heritage and archaeology might bring to the table. The feasibility stage will end on 31 March 2021 with a view to looking for funding to carry out some collaborative pilot projects based on learning and partnerships established in the feasibility stage.

Some of the reasons for working in this area are well laid out in just one of the UK's local authority's strategic needs assessments, which states the following:

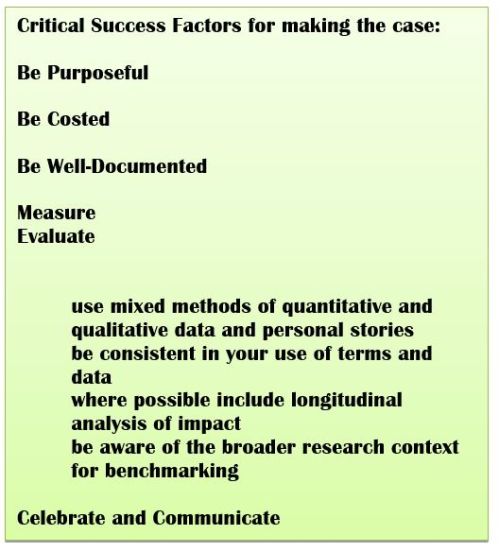

Figure 7 contains a list of possible success factors that might govern a successful outcome and which will be considered in the feasibility stage.

While investigating ways of doing something is crucial, there is a further issue of how to measure and evaluate success so that the benefits of action can be demonstrated. Part of the purpose for measurement and evaluation is to make the case for archaeology at various levels of governance, whether national or local; part is about constantly reflecting on methods and approaches to learn lessons on how to improve or adapt options for the future. This topic of wellbeing measurement is a large one and here I aim to focus on some key principles and guidance that currently exists to point towards approaches. As our pilot work progresses, we also hope to develop new guidance on what works best in what circumstances. Any such guidance will be made publicly available.

When talking about subjective wellbeing of individuals there are some helpful established assessments of what types of change in individuals – and to an extent, communities – engender a positive uplift in wellbeing. The New Economics Foundation example (Figure 8) shows some of these.

Our role as an historic environment body, therefore, might be to see how certain types of activity can produce the changes in individuals here identified on the bottom row. If we can show that some work carried out with individuals created an increase in positive feeling or increase in self-esteem, then we can rely on existing evidence, such as shown here, that links these changes to wellbeing outcomes. Simply put, if personal wellbeing is achievable by supporting confidence and resilience, self-esteem and feelings of competence then we should be designing projects that can achieve those feelings as collectively these will lead to improved wellbeing.

In terms of working with archaeological projects, there are many obvious ways in which involvement at pre-, main or post-excavation stage of individuals or communities could engender self-esteem, competence through skills learning, meaning and purpose. This could provide the foundations for what it is we are trying to assess when setting out on a project and wanting to think about what we might actually measure. Although there is considerable general anecdotal evidence for archaeological projects achieving many of these objectives, there is little rigorous recording of the degree or longevity of such changes. The next step is therefore to look at whether the project or programme records any changes in these areas.

For the recording to be most valuable its objective needs to be clear. For example, if it is simply a case of understanding your project and how it works then semi-structured interviews with participants can give you a feel for the sorts of experiences encountered. Engaging in this sort of evaluation before and after a project or programme enables some identification of change to be identified and can be especially useful in articulating the nature of change and creating stories of benefits to individuals for illustrative purposes.

However, if one of the objectives of the measurement and evaluation is to show what difference an intervention makes in a way that can be compared and contrasted to other methods, then it is essential to use validated methods with standardised approaches that are available to all. These enable comparison and a building up of evidence by collating data over time and multiple projects.

At the current time in the UK, the ONS provides one possible model and, most importantly, base-line data against which projects can be compared. However, at the scale most archaeological projects work, it is worth ensuring that base-line data is captured for the project at hand i.e. before the project begins.

In terms of a project-level subjective wellbeing evaluation the most cited is the so-called Warwick-Edinburgh model, a set of questions that have been validated for understanding and appreciation of the question and there are toolkits and advice available for how to use them. The shorter version of the Warwick-Edinburgh is recommended as a way to create a proportionate questionnaire for small projects. As with all evaluation, proportionality and awareness of the burden it can impose on participants is an essential consideration.

The What Works Centre for Wellbeing, one of several What Works centre set up by the UK government, has a wealth of advice, tools and methods available on its ever-expanding website. It also has conducted a scoping review of heritage and wellbeing projects.

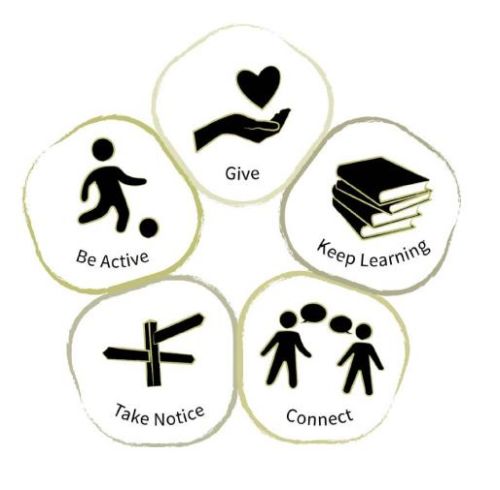

In this section, I want to look at the some of the reasons why archaeology works for wellbeing and some critical success factors for involving wellbeing in archaeology. In 2008, the UK Government Office for Science published 'Five Ways to Mental Wellbeing'. This identified five actions individuals could do which, in combination, would support mental good health and build resilience (see Figure 9).

I believe that if we looked at archaeology as practice, we could easily see how archaeological activities could enable all of these five positive and supportive approaches to self-care. Equally, if one takes the factors that the New Economics Foundation (NEF) identified (Figure 8) one can see how archaeology has the potential to create results in areas of confidence and self-esteem. Figure 10 provides an early attempt at capturing how and why archaeology might be especially well placed to deliver multiple outcomes in these two frameworks. The words in bold relate to the five ways to wellbeing, and the italics to the NEF framework. Added to this, and as referred to above, there are good opportunities within archaeology to articulate this benefit through upping our game in robust measurement, through adopting more rigorous evaluation techniques and considering the possibility of longitudinal evaluation to see longer term impacts and through capturing stories of individuals deeply affected by their connection to an archaeological project.

The proposition here is that when we start to consider projects and programmes in this way, we can start to see patterns emerge about the particular qualities of archaeology and heritage. Although this is only a high level and simple articulation of the relationship between archaeology and wellbeing, it might form the basis of what a 'unique selling point' (USP) for archaeology and heritage might look like when considering making the case for its collective benefits.

It is accepted here that there is more work to be done on issues of causality with regard to some of these suggested links. Given that wellbeing is as important in terms of thinking about how to design, deliver and measure a project as it is in terms of identifying specific objectives, it is worth thinking about what a model for a successful wellbeing project looks like. Listed below is a suggested way to approach a wellbeing project:

There are also arguably some key factors in successfully making the case for wellbeing outcomes, listed on Figure 11.

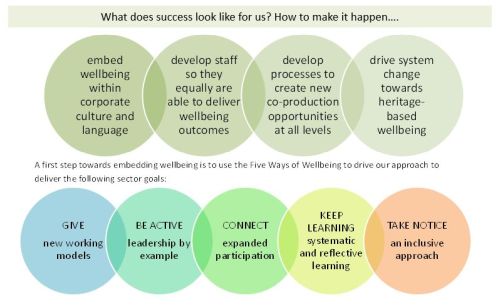

At Historic England, I am suggesting that we consider wellbeing as a journey. It begins with considering language and approach as much as anything else: doing with not doing to; and considering how co-production and co-creation could form part of many more of our conversations and projects. It would be unfair to assume that all staff would immediately buy into this idea and working with them to consider best ways of implementing ideas is crucial as well as training on what a wellbeing project might look like in particular contexts. However, wellbeing does not need to be seen as a completing a new strand of work that has to be done as an add-on to everything else. We are not asking people to become wellbeing experts as well as heritage ones, but we may be asking them to consider how to commission and design with others so that individual and societal wellbeing can be achieved. Figure 12 shows four stages on this journey.

One might argue that, like other heritage organisations, we have always been focused on care and protection, that the very nature of much of our work is rooted in sustainability of a valuable resource and creativity in how to elucidate that resource and celebration of its potential. Given this, maybe archaeology is especially well placed to adopt an approach that brings specific social benefits to its heart. Much of what is needed is about refining and shifting existing practice, thinking about what we are aiming for and being purposeful about how to get there. Decades ago, when the inclusion and diversity agenda became a topic in its own right and required to create awareness of need and potential, it helped establish methods that could be questioned and slowly evolve. It was considered that success would be achieved when it became a golden thread that ran through a project, programme, organisation, community and society. Maybe we would do well to consider the wellbeing agenda in a similar way – our goal to create a golden thread - engendering social change, addressing social inequalities and improving people's wellbeing in a highly tangible way.

I believe that creating successful wellbeing outcomes is the result of embedding it within a programme or organisation through language and attitude, developing staff so they know what it is about and how to recognise opportunities. After this, the things I refer to here, especially with regard to projects and processes can be applied to the way an organisation works (systems change), the way a project is delivered (e.g. research excavation) or the way a type of activity or programme is designed (e.g development-led archaeology). This is not to say it is easy or quick, but right now in a world questioning the dominance of Gross Domestic Product as the only way to measure policy success, it is especially relevant to consider how we can nudge change towards a more wellbeing orientated approach that puts improving people's lives at the heart of all that we do.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.