Cite this as: O'Keeffe, J.D.J. 2021 Archaeology 2030: A Strategic Approach for Northern Ireland, Internet Archaeology 57. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.57.3

In 2016, central government departments in Northern Ireland underwent a major reorganisation as part of the Reform of Public Administration (RPA). As a consequence, and for the first time in decades (if not the first time in the history of the state of Northern Ireland), all of the primary statutory heritage functions of central government around the protection of archaeological sites, monuments and artefacts, historic buildings, museums and galleries, and historical state records, were positioned under one government department. The Department for Communities is the largest department in the Northern Ireland Civil Service, and includes in its remit matters of sport, language, welfare benefits, pensions, child support maintenance, housing and regeneration.

This was a major change for the state sector in terms of how it contributes to the management of our historic environment, including archaeological sites and monuments. For some 40 years previously, these functions were exercised by the former Department for the Environment of Northern Ireland, which also included matters about nature conservation on land and in the sea, country parks as well as dealing with significant aspects of environmental crime (among what was, at times, a very broad remit). The Department of the Environment was also the lead government department dealing with the management of spatial town and country planning in Northern Ireland, and for the most part was the department responsible for issuing decisions around individual spatial planning proposals. As part of the Review of Public Administration, there was also a major reorganisation of local councils in Northern Ireland, reducing the number of councils from 26 to 11, and with significant new responsibilities passed from central government to those new councils. Most operational spatial planning functions have now been taken on by local councils, though the Department for Communities acts as a statutory consultee about development proposals that may impact upon the historic environment and advises appropriate conditions necessary for the treatment of archaeological remains in that context. The Department for Communities is still the regulatory authority for archaeological excavation in Northern Ireland, under the provisions of the Historic Monuments and Archaeological Objects (Northern Ireland) Order 1995.

With this major change in government structures, and with new Ministers in post in the Northern Ireland executive (government), attention within the heritage sector started to move from archaeology and heritage protection being seen largely through an environment lens to a keener focus on communities, people and societal impact. It is important to note too, just as had been the case for much of the rest of Europe, the economic downturn from 2008 onwards had a major impact on Northern Ireland. While archaeological fieldwork in commercial projects continued, it was happening at a much-reduced scale than previously. Discretionary funding for projects was very limited, and most centrally funded archaeological projects had halted by 2015, with attention focused primarily on core statutory obligations. It would be fair to say that the heritage sector at the time was feeling the strain, and not very optimistic about the future.

These changed times presented a valuable opportunity to re-establish connections within the sector, and to develop a sector-wide discussion about archaeology. While it was convened and initially led by government archaeologists, a core objective had been inclusion of the wider sector. Perhaps the most important aspect of the initiative was that it presented an opportunity to develop meaningful collaboration across the sector to develop a strategic approach to the challenges, and opportunities, for archaeology in Northern Ireland. The document that has emerged is not an imposed 'solution', nor is it owned solely by the regulatory authorities in Northern Ireland. It has been developed by the sector at large, with an expectation that it will be owned by the sector at large. Regulatory authorities will have an important role but, equally, individual practitioners, companies, community groups and institutions will have their part to play.

There had been, prior to 2016, ongoing discussion within the heritage sector in Northern Ireland around what archaeology was all about, who was involved and why, how was the work being done, by whom, and how much it all cost. There was, too, a certain disjointed debate around the value of heritage. For example, a Study of the Economic Value of Northern Ireland's Historic Environmentin 2012 had identified major positive benefits of the historic environment, including archaeological sites and monuments, which contributed at that time in excess of £500 million (gross) of output per annum, sustained some 10,000 full-time equivalent jobs, and for each £1 invested by the public sector some £3-4 was invested by the private sector, with significant scope for increase (DOE 2012a, 2). While local societal value was noted, along with reference to the intrinsic value of heritage as heritage, the primary focus of the reports was around economic value that was largely driven by tourism and the construction sector/built heritage regeneration. Indeed, the only recommendation in the report around archaeological excavation was made in the context of investment at sites for visitor access and tourism development (DOE 2012b, 63).

However, other issues dominated discussions for many archaeological practitioners, individually and within companies, institutions and indeed the government sector. Foremost were largely process-driven issues around the formation, recording, deposition and curation of the 'products' of archaeological excavation, specifically the issue of archaeological archives (Hull 2011). These elements, which underpin so much other archaeological work (and which are, in many instances, primary archaeological activities), continued to dominate the discussion in 2016, and indeed still continue.

In consideration of options to start a conversation, and in the time that followed, the discussions and debate at the 2014 symposium held at Amersfoort, the Netherlands, resonated powerfully with the present author, as there were key themes in common. The discussion revolved around how we, across the archaeological sector, were collectively managing our archaeological heritage. The proceedings of that symposium (Schut et al. 2015) were particularly relevant in moving the discussion forward, and central to this was the vision presented in the Amersfoort Agenda (Schut et al. 2015, 15-23). The vision of the Amersfoort Agenda offered reassurance: the kinds of issues that we were encountering in Northern Ireland were not unique, and there were positive approaches one could pursue.

Thus, in November 2016 the Historic Environment Division, an operational division within the Department for Communities, convened a symposium with invited participants from across the archaeological sector in Northern Ireland, including commercial companies, universities, professional bodies (the Institute of Archaeologists of Ireland and the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists), museums, and the community sector including the Ulster Archaeological Society.

In some respects, we found we were trying to construct a fire triangle: we had assembled the ingredients to create a reaction, and while we were not seeking to set the world on fire we certainly wanted to light a spark, to move the discussion forward and, most importantly, to work with one another to improve our collective management of the archaeological heritage (see Figure 1). At the first meeting it was clear that participants wanted to talk about how excavations were conducted, and how practitioners could achieve statutory compliance, but it was also very clear that collectively we wanted to talk about delivering something more and demonstrate greater public value that could be achieved by engaging in archaeology.

Our first meeting in 2016 was a tentative affair. While it was initiated by the Historic Environment Division, it was noted from the outset that it was to be an open gathering, not an assembly for induction or instruction. It was the first significant gathering from across the archaeological sector to discuss issues around the management of archaeological heritage in over a decade. There were always, of course, ongoing discussions between professional archaeologists in particular, but often these took place in isolation or away from a shared debate. The sector was perceived to be fractured, often according to the employment status held by one practitioner or another.

The following note appeared on an on-line discussion board:

There is a massive difference in pay, conditions and job security between archaeologists working in the private sector and archaeologists working for the state. Then there is rivalry between the various archaeological companies and the general animosity between field staff and companies over pay. At least the habit of some academic archaeologists looking down on everyone else seems to be a thing of the past. https://www.boards.ie/vbulletin/showthread.php?t=2057641311&page=2 [Last accessed: 1 March 2020])

For some the glass was half empty. To paraphrase some of the discussions and perceptions that had been expressed beforehand:

Conversely, others retained greater optimism:

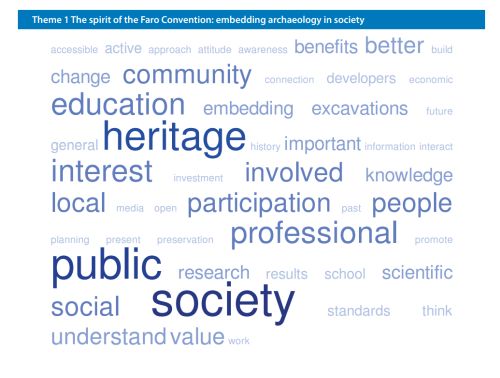

As one can see, what emerged in the discussions in November 2016 in Northern Ireland reflected very closely the kinds of discussion held in Amersfoort in 2014. While the United Kingdom is not a signatory to the Faro Convention (Council of Europe 2005), the language and themes of that convention can be observed in terms of what practitioners involved in archaeology are generally seeking to achieve. To that end, it would be fair to say that the text-boxes that express the three core themes of the Amersfoort Agenda (Schut et al. 2015, 16, 19 and 21) closely paralleled the kind of discussion that was emerging in Belfast. The words and phrases in the 'word clouds' from Amersfoort could just as easily have been drafted in the 2016 discussion in Belfast (see Figures 2, 3 and 4).

Following the symposium, Historic Environment Division drew together the notes and feedback from the day. In January 2017, Historic Environment Division circulated, for consultation, a draft 'Way Forward' document to the participants. The core themes that had emerged were:

Also, in January 2017, the Northern Ireland power-sharing executive collapsed. This was not a result of the archaeology discussion, of course, but it was a factor to be considered. At the time, no-one foresaw that it would be another three years until that Executive was re-established, and there was uncertainty about the purpose of continuing the discussion in the absence of a government minister. However, having started the conversation about archaeology, it was clear the participants wanted to continue. There was a consensus that a new way of approaching the challenges would be helpful, it would allow fuller engagement with the themes and deliver results that would benefit archaeology and the practice of archaeology for society.

The next stages of the process were convened by Historic Environment Division, but it was agreed that the success of the 'Way Forward' discussion would depend upon the participation and collaboration of a wide range of archaeological practitioners. Task Groups were set up for each of the four themes, with senior representation from Historic Environment Division on those groups but chaired by individuals outside of central government and with representation from across the wider sector. Following much discussion of the themes the groups eventually produced discussion papers to further explore and progress the issues to a Steering Group, also convened by Historic Environment Division. The Chairs of each of the Task Groups sat on the Steering Group, and over the next two years made significant progress in discussing and reporting the issues, along with emerging recommendations. Officials from Historic Environment Division then gathered and refined the recommendations, in consultation with the Chairs of the Task Groups.

In July 2019, the wider group was gathered once again, this time to consider a discussion document that set out the conclusions of the Task Groups and a pathway to agreeing a final version of the recommendations. The discussion in July 2019 was very open in terms of considering the challenges and opportunities presented in developing the document as a strategic direction for archaeology (see Figure 5).

The Steering Group considered the feedback from the meeting, and over the months that followed finalised the document, again in close collaboration with the Chairs of the Task Groups. This aspect of collaboration was crucial to the success of the enterprise, and included endorsement from the Institute of Archaeologist of Ireland and the Chartered Institute for Archaeology (CIfA/IAI 2017).

The process has led to the compilation of a new document, Archaeology 2030: A Strategic Approach for Northern Ireland. It is a collaborative document, compiled by a broad spectrum of the archaeology sector in Northern Ireland, and has the following as its key vision statement:

We want archaeology to be accessed and valued by as many people as possible, led by a sector which is healthy, resilient and connected.

In order to achieve that vision, there are a series of priorities, objectives and recommendations for action, under the following headings:

The document also contains proposals around the next steps, how to progress the priorities for action and deliver upon them. Those next steps will be key to continuing the success of the process. One could not have foreseen the impact of the global coronavirus, COVID-19, as the Way Forward process happened, but no doubt it will need to be taken into account in the next steps too.

In essence, the Way Forward process and now the Archaeology 2030 document draws sharp focus around four areas:

The strategic approach is being brought forward as a 10-year document. It is recognised that it covers a lot of ground, and it will take time to change processes, systems and perceptions around archaeology. What has perhaps been most important, however, has been the process of co-design across the archaeology sector. The process has enabled new conversations and provided a space for practitioners to speak with one another on matters of both common and divergent interest. This is not to say that those conversations could not happen otherwise, but the process has enabled a coming together within the sector that has been positive and which was unlikely to have happened at the time had the Historic Environment Division not initiated the process.

This has been a long process. In part this is because most participants took part in a voluntary capacity, fitting it into their workplans and spare time. It also reflects, very much, that the issues under discussion were not easy, that there were divergent views about what success or progress might look like, and that it will continue to be a learning process, until 2030 and beyond.

Reflecting on the Amersfoort Agenda, one can see connections to the three themes, viz.:

While recognising that the Faro Convention has yet to be adopted by the UK, the desire for embedding archaeology in society is very clear. By way of observation, in a Northern Ireland context local history and, by extension, local archaeology, is very seldom taught in schools as an 'official' subject. Archaeology and key major monuments are included in the curriculum, but usually in the context of certain themes such as first settlers or the Stone Age, the Vikings or the Normans. For older schoolchildren, history is taught with particular emphasis on western European/north Atlantic, British and to a degree Irish national history (though the national curriculum does make provision for other topics too). There are many individual teachers who will inject discussion of local sites and places, traditions and tales, but for the most part, there is limited opportunity for those first 14 years of educational life for children and young people to engage with archaeology in the formal educational setting.

However, society at large engages with the historic environment every day, and it is evident that a very large component of this is through social interaction, within the places that people live and the wider community. There are many active local history societies, which act both as places of social interaction and as places of life-long learning and sharing of knowledge. There is a particularly strong association with places, and this is revealed through place names and the symbols of those places found in school crests, the insignia of sports clubs, fraternal societies and civic heraldry. Many of these crests and insignia incorporate locally important monuments, buildings or other cultural features in the landscape. In the course of the lockdowns arising from COVID-19, there has been renewed interest in many of the 'open' historic monuments that provide space for exercise, reflection and access to the outdoors.

So far, the process has been largely introspective. While it has engaged the archaeological sector beyond development-led archaeological excavation, it has yet to engage wider society, be that the primary funders of most archaeological work (that is, those involved in spatial development and land-use change, be they private sector or public/state bodies) or the group that is cited as the primary beneficiary of the work, that is, society at large.

There remains much work to be done around procedural elements, the legislation, policy and practice element of archaeological excavation and the curation of the material arising from excavations. There is also a clear willingness of professional practitioners to develop standards and processes around the activity of archaeological work. That said, there was also a focus within some of the discussion about the development of new rules and codes, and greater enforcement of the existing provisions, including punitive measures. This has caused the present author some concern and brought to mind a conversation with a past president of the EAC at the symposium in Athens in 2017 (de Wit pers. comm.). In that conversation, about rules and regulations, he noted that there can be a tendency, where one rule or other is not being observed, to introduce a new rule that makes the first one more robust. Sometimes this works, but there may be unintended consequences, outcomes that were not anticipated, and so another new rule is developed and so on. Ultimately, one has to recognise that the enforcement of any rules will depend upon their necessity, the resources available to conduct any enforcement, and the willingness to comply of those subject to the rules. It is my view that this runs the risk of making the process the most important thing, rather than the outcome, and in any case, resources are always stretched: co-operation would be better than coercion.

Perhaps the most important aspect of the process so far has been establishing and keeping open lines of communication within the sector. This has not always been easy! The archaeology sector in Northern Ireland is small, and there has been a genuine engagement that has committed resources – especially time – for practitioners to take part in the discussion. But there are also continuing issues of 'hard-to-reach' stakeholders within the sector. Perhaps this reflects strains on their own resources, or an expectation that little will change despite the discussion. Conversely, there have been challenges about managing expectations. In particular, the ongoing challenges of resources, public or private, to enable the changes sought have been to the fore in discussions. This is likely to continue to be a continuing issue as the process moves forward.

The coming together has been an opportunity to think beyond the immediate challenges, and to work collaboratively toward solutions. If one considers how the sector has engaged, and without reading too much into the body language of one image, Figure 5 tells something of its own story. Some participants were eagerly engaged, putting forward ideas and arguments, examples and complaints. Some were relaxed in the conversation, while others were less engaged, defensive even. Others again were preoccupied, engaging with the process but also having to deal with their day-to-day activity. But they were all present, taking part. This has been an achievement that everyone in the process shares.

When the final papers were received from the Task Groups, they contained over 300 recommendations. These have been condensed down to the five core aims with five or six key recommendations, but behind these there are multiple actions that will need to be addressed over the coming years. That will require the oxygen of more space and time for the conversations, the heat of continuing collaboration and determination, and reliance upon the fuel of the archaeological resource and public interest. The fire triangle (Figure 1) will need careful attention.

Looking forward, maintaining the heat in the process will be challenging. It will require similar conversations to be had many times. One of the participants in the process, from a community background, noted that for the archaeologists involved there was a long story that they were familiar with, but that for the wider public much of the story was not known, and there was a clear need to communicate the same message again and again as new participants joined the conversation. In this way, perhaps, the process of embedding archaeology in society can progress, but underpinned by how we work (our standards) as much as why (our professional obligations and statutory compliance), and a willingness to engage outside of the sector early and often.

The sector engaged in something new in taking part in the process. At its most commonly understood definition, archaeology is the study of the past through material remains. To put this another way, archaeologists take the material world, the physical remains of the past, and dismantle those remains, sometimes to destruction. Through that process the archaeologist interprets the remains and uses that interpretation to tell a story of the past. Essentially, archaeologists take the physical world that has survived from the past and turn that physical world into ideas. Those ideas then form the basis of our story-telling, our narration of the past as it is understood now, and in the future new ideas will challenge that narrative.

The greatest challenge now in this process is to take the ideas arising from Archaeology 2030 and turn them into physical things, to convert that to a reality for practitioners across the sector, and to embrace and welcome wider society into the process.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.