Cite this as: Duong, M. 2021 Development-Led or 'Preventive' Archaeology in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, Internet Archaeology 57. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.57.6

Luxembourg's archaeological tradition is relatively recent. The very first legislation regarding both archaeology and archaeological heritage dates back to 1927 and 1937 respectively. At that time, archaeological heritage was the responsibility of the Ministry of Education, and the public servants in charge of archaeological heritage were professors and teachers.

The first archaeologists were hired by the State in the 1960s, following the promulgation of a new law regarding archaeological excavations in 1966 (Paulke 2015; Loi du 21 Mars 1966). Since then, the Ministry of Culture (formerly Ministry of Art and Science) has been responsible for archaeology and archaeological heritage across the national territory. The legislation regarding the protection and conservation of national monuments dates back to 1983 (Loi du 18 juillet 1983).

At present, archaeological heritage is managed by the National Archaeological Research Centre/Centre national de recherche archéologique (CNRA), which was legally founded in 2011, under the responsibility of the Ministry of Culture (Règlement grand-ducal du 24 juillet 2011).

In compliance with the law of 1966, a ministerial authorisation is required for all excavations and archaeological investigations: 'Research or excavations with the aim to discover or excavate objects or sites of historic, prehistoric, palaeontological or otherwise scientific interest may only be undertaken with prior authorisation of the Ministry responsible for the arts and science'. (Original text: Les recherches ou les fouilles ayant pour but la découverte ou la mise au jour d'objets ou de sites d'intérêt historique, préhistorique, paléontologique ou autrement scientifique ne peuvent être entreprises qu'avec l'autorisation du Ministre ayant dans ses attributions les Arts et les Sciences.)

According to the law of 1983, accidental or chance discoveries of objects or archaeological structures have to be notified to the authorities. If archaeological structures are discovered during ongoing building works, the mayor of the location in question must be informed, who in turn is under a legal obligation to pass on the information to the Ministry of Culture, or directly to the CNRA. In such an instance, the CNRA has to assess the archaeological structures unearthed on site, and decide what can be done. It is possible to stop the construction work, to allow the CNRA to plan or to carry out an archaeological excavation. Should an archaeological site need permanent protection, it can be listed as a 'national monument' and is then protected by law.

Owing to the fast development of the country and a steady increase in population, there are numerous ongoing public and private construction projects in Luxembourg. This led to the development of the practice of preventive archaeology in the early 1990s. The first preventive archaeological operations involved monitoring road constructions: in 1990 the National Roads Administration (Administration des Ponts & Chaussées) hired a small team of archaeologists to monitor and control major road construction. When more important archaeological structures were discovered during these construction projects, trial-trenching was also carried out (Le Brun-Ricalens et al. 2003; Le Brun-Ricalens and Schoellen 2000). The National Museum of Art and History (MNHA) also carried out trial-trenching in the early 1990s, but only within the framework of large projects, such as that of sand or stone quarries (Le Brun-Ricalens 1993; Le Brun-Ricalens 2001).

The discovery of several major archaeological sites during these first preventive archaeological operations has proven the importance of this approach. Two years after the legal foundation of the CNRA, a new department for archaeological monitoring of land development was created within the CNRA, called Service du suivi archéologique de l'aménagement du territoire (Pösche 2016).

The aim of this department is to develop 'preventive archaeology' in Luxembourg by assessing the impact of urban development projects on known or suspected archaeological sites, and to recommend archaeological field evaluations if necessary, in order to reduce the impact of construction works on archaeological heritage.

Despite the creation of this department, there is no legal framework for development-led or preventive archaeology in Luxembourg at the time of writing this article. Luxembourg signed the ratification of the Valletta Convention only in December 2016 (Schoellen 2017-2018; Loi du 7 décembre 2016). For the following three years, the Ministry of Culture was drafting a new law to implement the principles of the Valletta Convention, among other elements regarding the protection of cultural heritage in Luxembourg. This draft law was submitted at the Government Council in August 2019 (Projet de loi relatif au patrimoine culturel (no. 7473)). Therefore the activities of the CNRA take precedence over the national legal system in Luxembourg regarding preventive archaeology and 'integrated conservation' of the archaeological heritage.

Currently, if a project is likely to have an impact on an archaeological site, the CNRA recommends carrying out an archaeological field evaluation. This may take the form of archaeological monitoring, a geophysical survey, trial-trenching or an archaeological excavation in order to detect, expose, record and rescue the threatened site (and/or artefacts) before construction works begin. For projects evaluated within the framework of a given environmental impact assessment, the CNRA or the Minister of Culture issues a prescription (or expectation) rather than a recommendation.

When the draft law becomes regulation, all development projects will have to be assessed by the CNRA, except for certain types of project less than 100m² in a known archaeological area, and those below 1 hectare in areas where no archaeological site is known. All assessments of projects can lead to a prescription.

In order to shorten the process of project assessment, the desktop study of incoming new projects has been set to a maximum of 3 weeks. In practice, the CNRA can even issue a recommendation or a prescription within 3 days for urgent cases (i.e. when a developer has already received an authorisation from a mayor and is about to start construction works on the following day). But since the number of projects to be assessed will be doubled or even tripled once the upcoming law comes into effect, the assessment period will be extended to 30 working days.

Geophysical surveys and trial-trenching are currently undertaken by accredited private archaeological firms, and financed by project developers. There are three such firms in Luxembourg (who employ a total of 17 archaeologists) for trial-trenching, which is the most common method recommended or prescribed by the CNRA. Geophysical surveys are recommended only for large-scale projects on large open and unbuilt areas. Owing to a lack of experts in geophysical surveys related to archaeology in Luxembourg, this type of survey is carried out by foreign firms.

When the CNRA issues a recommendation or a prescription after assessing a project, the project developer also receives all necessary scientific and technical specifications from the CNRA, which both the developer and the private archaeological firm needs to respect when carrying out the fieldwork. Once the developer has chosen an archaeological firm, the archaeologist in charge of the operation drafts a field survey plan, which is sent to the CNRA for assessment. An authorisation from the Ministry of Culture also must be requested in order to undertake the recommended or prescribed operation, because all excavations and archaeological investigations in Luxembourg require ministerial authorisation to comply with the law of 1966. With the future law, a ministerial authorisation will still be a requirement for all types of archaeological operations.

As of today, it can take up to 3 weeks to obtain ministerial authorisation, but in practice the CNRA always tries to follow the three operators' planned fieldwork closely, and to ensure that the authorisations are issued before operations start. To avoid potential delays, the CNRA also requires a meeting with the project developer and the archaeologist in charge of the operation prior to the beginning of a field operation. This might seem to be a minor element in the whole process, but within the framework of raising awareness, we realised that a short meeting on site with all the parties can often sort out potential issues more efficiently. Therefore, we have introduced this new requirement into the general process in 2018, as well as into the draft law.

The duration of archaeological operations depends on the size of the area that needs to be surveyed. Geophysical surveys can usually be done within a day or two for projects up to 3 hectares. Trial-trenching is carried out within 2 to 3 days for projects up to 1 hectare, depending on the topography, whereas the duration of an excavation is much longer and depends on many factors. The law that has been submitted states that each archaeological operation should not exceed 6 months, extendable to 12 months.

At the end of an archaeological operation, the private firm produces a technical and scientific report. This report, as well as all archaeological finds uncovered during the trial-trenching, must be delivered to the CNRA either within 30 working days after the end of the operation if archaeological features have been discovered and a further extensive excavation might be needed, or within 6 months if the operation did not uncover any archaeological features.

Depending on the importance of the archaeological structures discovered during the field evaluation, the CNRA can prescribe an extensive archaeological excavation. These are currently undertaken by the CNRA and financed by the State, except for projects evaluated within the framework of given environmental impact assessments, which are financed by the project developer (Loi du 15 mai 2018 Art. 3(1)4). With the future law, geophysical surveys and trial-trenching will still be financed by project developers, since they are considered as the 'polluters', whereas the costs of archaeological excavations will be divided into two and financed by both the State and the developers.

Currently, should a developer choose not to carry out an archaeological operation despite the CNRA's recommendation or prescription, there is not much that the CNRA or the Ministry of Culture can do. However, if archaeological remains are found during construction works, the building site can be halted until an archaeological evaluation is carried out by the CNRA. Since the disruption of construction works is usually a source of major financial losses, most developers have a practical approach and choose to finance archaeological field evaluations as recommended or prescribed by the CNRA. With the upcoming law, this issue will in theory be minimised, because almost all projects will have to be assessed by the CNRA, and prescribed field evaluations will therefore be undertaken before construction works begin.

Some archaeological sites in Luxembourg have national monument status, which is the highest protection level that a cultural monument can benefit from the State in Luxembourg.

If a development project affects a building protected as a national monument, or located within the area of an archaeological site protected as a national monument, an authorisation from the Minister of Culture is required. This authorisation states whether the planned construction works can be carried out or not and, if so, in what way. These projects are analysed by a specially appointed commission, called the Commission des Sites et Monuments Nationaux (COSIMO) (Règlement grand-ducal du 14 décembre 1983). Since the CNRA is also a member of this commission, the agents of the CNRA give their recommendations directly to this commission upon receipt and assessment of a project located within the area of a national monument.

However, it is worth noting that only a small per cent of known archaeological sites have the status of a national monument: with about 110 archaeological sites out of the 7500 known in Luxembourg being protected in this way. In 2014, only 15 archaeological sites were protected as national monuments. Another 200 archaeological sites are considered worth being classified as national monuments, and this number keeps growing as new sites are discovered through field surveys or research studies of historical maps or LiDAR data.

Throughout the years, the CNRA has developed several approaches to raise awareness of the public benefits of preventive archaeology. From 2013 to 2015, the CNRA developed an archaeological map within the legal framework of general development plans in Luxembourg (see explanation about the amendment of the general development plan (PAG)). The general development plan, known as 'plan d'aménagement general' (PAG), divides the territory of each commune in Luxembourg into various zones. For each zone, the PAG defines the types of use that can be made of each land, as well as the amount of construction that can take place on each plot.

The archaeological map that we developed divides the country into three archaeological zones. These zones reflect the three different levels of archaeological potential. All the communes in Luxembourg received this archaeological map, along with explanations and instructions regarding the administrative procedure of preventive archaeology. The three zones on the archaeological map are meant to be integrated into the PAG, so that developers can see whether their construction projects could have an impact on archaeological heritage or not, and whether they should send their development projects to the CNRA for assessment (Règlement grand-ducal du 8 mars 2017, Art. 38).

Since 2015, the CNRA has given lectures on the public benefits and the administrative process of preventive archaeology within the framework of a lifelong learning programme regarding urban and rural planning, offered by the University of Luxembourg (Formation continue en aménagement du territoire, University of Luxembourg).

Since most participants in this lifelong learning programme are architects and urban planners, they share their awareness about preventive archaeology in Luxembourg with their colleagues and clients. As a result, the number of archaeological assessment requests increased through the years, notably thanks to these lectures.

The step-by-step guide about the administrative process of preventive archaeology published on the CNRA's website in 2016 is another useful tool that we developed to raise awareness of the public benefits of preventive archaeology. In 2017, 2000 copies of a leaflet containing the same information was printed and sent to construction development firms, architects, consulting engineers and mayors of the 102 communes in Luxembourg (see Guide l'Aménageur PDF).

Generally, developers from large companies, consulting engineers, and major architecture firms are those who are more inclined to send in their projects for assessment. Engineers, architects and mayors of some communes, especially from those that have outstanding archaeological sites located in their municipal territory, have also understood the advantages of preventive archaeology. The commune of Schieren for instance, where a large Roman villa (with a pars urbana and a pars rustica), known and excavated since 2007 as a result of the construction of a new freeway, has showed an immense interest in preventive archaeology. The representatives of the commune organised a conference to present the latest archaeological finds from this ongoing excavation to the public, and they also inform the CNRA about every new private development project as soon as they are contacted by a developer.

However, it is still a challenge to convince mayors of large cities or towns, as well as small-size developers, to practise preventive archaeology.

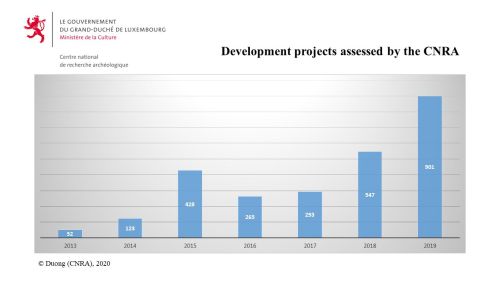

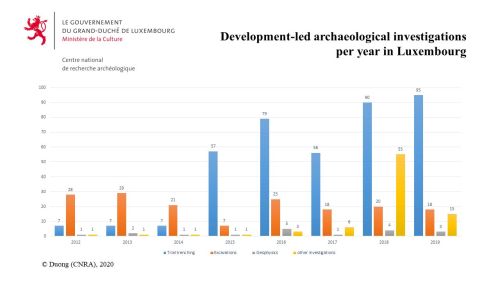

The department of archaeological monitoring of land development (Service du suivi archéologique de l'aménagement du territoire) was founded in 2013, and the assessment of construction projects started shortly afterwards. The number of projects assessed by the CNRA climbed from roughly 120 in 2014 to 900 in 2019 (Figure 1). The increase in assessed projects naturally leads to an increase in archaeological operations. Since 2016, an average of 85 trial-trenching and surveys have been undertaken per year, compared to previous years, when less than 10 geophysical prospections and trial-trenching were carried out per year (Figure 2).

The number of excavations, however, has stayed around 20 per year. This is mainly because excavations are carried out by the CNRA, which lacks personnel. In fact, the number of proposed excavations has also increased, but since it is not possible to do more excavations per year, the waiting list keeps growing. There is not only a lack of personnel, but also of public financial support for archaeological research, be it for excavation, publication or laboratory research. With the upcoming legislation, the allocated budget will be increased, but it is hard to predict if it will be sufficient, since on the one hand, the workload will increase and on the other hand, the 'polluters' will pay 50% of the excavations.

The question whether private project developers should be legally obliged to pay for surveys and trial-trenching, and to participate in the financing of excavations still needs to be raised.

Is it fair that private individuals who only want to build a small house also have to pay 50% of the costs of an excavation, which can be more expensive than the house itself? According to the proposed law, the State does not offer any funding to help project owners who are obliged to carry out field surveys. However, the State does provide help to owners who want to renovate their house if it is protected as a national monument (Règlement grand-ducal du 19 décembre 2014).

How should the costs of an excavation be fairly split into two halves? Should the State or the project developer find an operator and make the deal? Once both parties have agreed to the terms, and if an excavation needs to be extended owing to unexpected discoveries, will the developer accept the excavation being extended and keep financing the operation? If the developer refuses to continue financing, should the excavation simply be stopped? Clear guidelines need to be established on this matter.

The construction industry in Luxembourg is healthy and growing, with continued housing demands. According to the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies of Luxembourg (Statec), the prices have doubled in ten years, and the average price of a new construction in 2018-2019 is around 6700€ per square metre. If project developers have to finance half of an excavation, the housing prices will certainly increase, as these costs will be added to the selling price, which conflicts with the current political aim.

Regarding the duration of archaeological operations, the forthcoming law foresees that each operation (whether it be trial-trenching or extensive excavation) should not exceed 6 months, which can be extended to 12 months. While this can be acceptable for trial-trenching, it is clearly not feasible for excavations. A shorter deadline will certainly lead to a lack of quality in archaeological investigations. This should be avoided.

In addition, the following tasks that are important to development-led archaeology have not been specified in the recently submitted draft law:

Public benefit is yet another challenge for development-led archaeology. If the State wishes to further develop preventive archaeology by giving more funds and personnel to carry out additional archaeological investigations, and by demanding that developers pay for archaeological surveys and perhaps half of archaeological excavations, it is clear that we also need to deliver more benefits to the public.

The State already offers access to information about archaeological sites by giving conferences and tours of specific archaeological sites throughout the year, as well as developing various tools such as virtual guides, augmented reality media guides with 3D reconstructions, and smartphone applications for children and tourists (see Rapport annuel d'activités 2019 du CNRA, 7-9). In addition, the Minister of Culture has also decided to make the archaeological inventory public. Moreover, the draft law foresees public consultation for the creation of a national zone, which is 'free' of archaeological remains: developers or owners of plots will be able to help work on this new map by providing proofs that certain areas do not and cannot contain any archaeological remains. Or, conversely, that certain areas need to be added to an archaeological zone because they can prove that there are still archaeological remains under an already built plot.

But is this enough in terms of public benefit? The State might have to encourage greater public participation in decisions about preserving archaeological sites. In order to do this, we should reach out to the public, not just to a public that already shows a great interest in archaeology, but also to a public who are not yet particularly interested in cultural heritage, but who are or will be confronted with the matters of preventive archaeology, especially developers. To reach out to this type of public, perhaps it is best to go through a regional or local level – that of the communes, since communes are in charge of the general public's welfare in their daily life.

Therefore, it is important to keep cooperating with local authorities to promote public involvement with archaeological heritage. Communes sometimes organise special meetings for its residents to learn more about a specific urban development plan or future construction project. During these meetings, they can inform the public about potential archaeological surveys recommended by the CNRA, or investigations already undertaken within the framework of the said projects. It would be wise if an archaeologist from the CNRA were present at these meetings to answer the public's questions, and thus to develop connections with the public.

The State, and especially the CNRA, should also keep promoting the existing collaboration with private development companies. Developers could also organise public visits to excavations undertaken within the framework of their development project.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.