Cite this as: Geser, G., Richards, J.D., Massara, F. and Wright, H. 2022 Data Management Policies and Practices of Digital Archaeological Repositories, Internet Archaeology 59. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.59.2

This article presents the results of a survey of data management policies and practices of digital archaeological repositories in Europe and beyond. The survey was carried out in 2021 under the auspices of the European project ARIADNEplus and the COST Action SEADDA (Saving European Archaeology from the Digital Dark Age). The aim of ARIADNEplus is the creation of a European research data infrastructure by aggregating datasets from multiple countries, whereas SEADDA is focused on capacity building for archaeological data preservation and reuse. Our article supplements the special issue of Internet Archaeology 'Digital archiving in archaeology: the state of the art' (Jakobsson et al. 2021), which provides national snapshots of the current situation regarding data curation for 22 countries. It also supports the goal of the SEADDA COST action to review current international best-practice guidance, providing recommendations for expansion and improvement where needed.

The main purpose of the online survey was to collect and analyse information about current policies that determine access and reuse for data held by digital archaeological repositories, and to investigate the guidance and support needed to make the repositories and data FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable). These policies comprise the regulations of heritage and research authorities and funding agencies, and institutions at different levels (European, national, regional, and local) as well as the rules of the repositories themselves for data deposition, access and reuse. The repositories are operated both by heritage sector institutions as well as by the research and higher education sector. The survey adopted a bottom-up approach by focusing on the actual policies and practices of the repositories. While these may reflect higher level regulations, a bottom-up approach was deemed preferable as it allows an evaluation of the extent to which current policies and practices conform to the FAIR principles and facilitate open access data. These increasingly inform higher level regulations. A reality check can enable heritage and research authorities, funders and other institutions to reinforce or put in place regulations that bring current repository policies and practices closer to the ideal. The survey results show that there is room for improvement in this regard.

This section explains the main context of the survey, describes archaeological data management as regulated by authorities within the heritage as well as research and education sectors, and addresses relevant European data-related policies.

The main context of the survey consists of the goals of SEADDA and its 'sister' project, ARIADNEplus, regarding the development of repositories appropriate for the management and sharing of archaeological data.

The original ARIADNE project (2013-17) set up a digital infrastructure enabling the discovery of and access to datasets held by existing archaeological repositories in Europe (Aloia et al. 2017). It was recognised that there was a need to promote and support the development of data archiving solutions in many countries where archaeologists lacked appropriate repositories to deposit and thus make their data available to the research community and other users (Wright and Richards 2018).

In 2019, ARIADNEplus and SEADDA started with complementary objectives: SEADDA fosters the development of archaeological data repositories, while the ARIADNEplus platform enables finding and accessing data that is being shared through existing and nascent repositories, providing search and access across the participating institutions.

The COST Action SEADDA involves ARIADNEplus partners and institutions from several additional countries, with representation from nearly all European nations as well as wider international participation (Argentina, Canada, Israel, Japan, Turkey, Pakistan and the United States). The SEADDA network supports institutions seeking to develop archaeological data repositories that take account of heritage regulations, and which are able to curate and make accessible varied and complex data. In archaeology this often requires specialist domain and technical knowledge.

In recent years FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable) data and FAIR-enabling repositories have become an important topic in the research data management community. The FAIR data principles (Wilkinson et al. 2016) are being adopted by ever more research funders, often in addition to their open data agenda, i.e. that data collected or generated by publicly funded projects should become publicly available.

The ARIADNEplus and SEADDA initiatives support these principles, but efforts to improve the management and sharing of archaeological data must take account of the realities of existing archaeological practices. Articles published in Internet Archaeology 58, co-sponsored by SEADDA and the European Archaeological Council, describe such practices and make clear that the repositories are keen to continuously improve them (Jakobsson et al. 2021).

Initiatives that raise awareness and support capacity building for FAIR data, e.g. European Open Science Cloud, FAIRsFAIR, GO FAIR, and many, perhaps too many, (Dunning et al. 2019) other initiatives are valuable as they prepare the ground for further, more specific actions by communities and institutions from different disciplines.

The tendency to impose generic FAIR and open data criteria that researchers and repositories should fulfil is less helpful. It would be better to help to change and improve long-standing data practices. The situation is inevitably fragmented, which is unsurprising, considering various factors such as established rules and routines, limited resources, IPR and copyright, legacy technology and metadata, among others.

There are projects that aim to develop intricate sets of indicators for FAIR data measurement and evaluation, ideally by means of automated procedures (e.g. Devaraju et al. 2020, Devaraju et al. 2021, FAIRsFAIR F-UJI; Wilkinson et al. 2019, FAIR Evaluator). Such evaluations will only scratch the surface of what constitutes actual data-related practices, which remain a 'black box' and, owing to their complexity, are unlikely to adjust to proposed improvements.

Rather than proposing seemingly easy improvements detected at the surface, the question is how to support changes in ingrained data-related practices so that the outcomes gradually align with the request of being FAIR and providing open data.

The management of archaeological data by researchers and repositories is regulated by the policies of different agencies, including heritage authorities, research funders and other institutions. Most primary archaeological data is generated by archaeological fieldwork (including survey and excavation). This is regulated by heritage authorities via permissions and related conditions. Permissions may be granted for preventive archaeological work (i.e. rescue excavations) as well as fieldwork undertaken as a part of academic research projects. The conditions generally require documentation of the fieldwork in a report, sometimes according to a specified reporting template.

The production of such reports is usually based on data generated during the fieldwork. The conditions set for such data vary between countries, ranging from deposition in a mandated state-of-the-art repository (e.g. in the Netherlands, the E-depot for Dutch Archaeology) to the expectation that the organisation of the permission holder keeps and preserves it.

A survey by the European Archaeological Council (EAC) in 2017 addressed practices of decision-making in archaeological heritage management, including how fieldwork documentation is being archived and published. Based on the responses of 22 representatives of EAC member states and regions the survey report concluded that "Lack of policies on digital archives is common".

The survey found that storage of physical objects is quite well established as over 75% of respondents said that objects are placed in some form of state archaeological storage. But the archiving of documents (reports, data) was less satisfactory: "Fewer states (n=7) specifically reported a formal documentary archiving system. One state (Czech Republic) reported that they have no specific policy on documents. Few states referred specifically to digital archives, although this will surely be a significant factor in the coming years. Two (Hungary and Northern Ireland) noted the absence of a digital archive policy; others referred to the existence of databases of archival material" (European Archaeological Council 2018, 3 and 25).

The survey mainly concerned the digital archives and repositories of heritage bodies to which the operational tasks of heritage management are delegated (e.g. museums or local authorities). However, bodies within the research and higher education sector (e.g. research councils, universities, research centres) may also regulate how researchers have to ensure the preservation of, and access to, the publicly funded data of completed research projects. For example, they can require deposition in a mandated archaeological data repository (e.g. the Archaeology Data Service in the UK), a subject-based repository that specialises in certain types of data, or the institutional repository of a university or research centre.

Therefore different regulations can apply, and the organisations that operate repositories can be heritage sector institutions, or in the research and higher education sector. These regulations are taken into account by the repositories in their rules and specific conditions and procedures. Regulations covering archaeological data are usually set by institutions in the country where the researchers and repositories are located. However, in recent years European level initiatives have often driven the open and FAIR data agenda for publicly funded data created in research and public sector institutions, including heritage bodies.

In 2012, the European Commission issued the Recommendation on Access to and Preservation of Scientific Information (2012/417/EU). The Recommendation sets the agreed common strategy for the EU Member States to implement open access to publicly funded research publications and data. The Recommendation primarily concerns authorities, funders and organisations performing research, including their libraries, repositories and other research infrastructures. In 2018 the Recommendation was updated to reflect recent developments in research practices relating to Open Science and the European Open Science Cloud initiative (European Commission 2018a).

The Member States and three associated countries (Norway, Switzerland, Turkey) regularly report on measures taken in line with the Directive; progress reports have been published by the European Commission (2015; 2018b; 2020a). These reports do not address particular fields of research, but the requirements for open access to research publications and data concern all disciplines, including archaeology.

Since 2003 access to information held by public sector bodies in the European Union has been regulated by Directive 2003/98/EC on the Reuse of Public Sector Information, substantially amended by Directive 2013/37/EU. Research and educational institutions were generally not included in the Directives 2003 and 2013 (Richter 2018). A major modification in 2013 was the expansion of the Directive's scope to include publicly funded libraries, archives and museums, although the focus was on cultural and heritage management data, not research data. The content may be used for research but is not data generated by research.

The impact of the 2013 Directive on cultural heritage institutions was fairly limited, owing to some exceptions and privileges regarding IPR, copyright and charging (Communia 2014; Keller et al. 2014). The Directive concerned only content already available in digital formats; it did not oblige cultural institutions to digitise content and it did not provide a common framework to mobilise European and national funds for digitisation. Therefore more important was the European Commission's Recommendation on Digitisation and Online Accessibility and Digital Preservation of Cultural Material (2011/711/EU) with dedicated promotion, support and monitoring of digitisation efforts of the Member States (Deloitte 2018, 151-73).

This recommendation is the Commission's main instrument for digital cultural heritage. A revision is currently planned to ensure it is still fit to respond to the challenges and needs of the sector. Therefore an extensive evaluation of the impact of the recommendation has been conducted (European Commission 2021), including the results of a public consultation in 2020 on the expectations of stakeholders (565 responses) regarding digital cultural heritage (European Commission 2020b).

In 2019, the 2013 Directive was replaced by the Directive (EU) 2019/1024 on Open Data and the Reuse of Public Sector Information, also called the Open Data Directive. This Directive has been in force since 16 July 2019, and was to be incorporated by Member States into national law by 16 July 2021 at the latest. For the repository survey, Article 10 of the Open Data Directive is important. This aims to make research data funded, collected or generated by public sector bodies openly accessible and reusable (see the briefings on the Directive by OpenAIRE 2021; Pilar and Lewandowski 2019; SPARC Europe 2019; for legal discussion Gobbato 2020).

The Directive addresses governmental bodies, bodies governed by public law, and organisations owned or governed by them. Therefore there is a wide spectrum of public sector bodies that are now subject to open access policies for their research data, including many more than those covered by the Recommendation on Access to and Preservation of Scientific Information. It includes, to give but a few examples, governmental heritage authorities at all levels (national/regional/local), heritage agencies or associations established by public law, research-intensive public museums, and other heritage institutions.

The Open Data Directive focuses on their institutional or subject-based repositories, because its purpose is to make publicly funded research data they hold accessible and reusable. The Directive applies only to research data 'documents' made available in a digital format; research papers in journals or conference proceedings are not addressed. However, archaeological fieldwork reports are included within the broad definition of 'documents'. Nonetheless, it is important to note that the Directive does not require digitisation of documents and should also not impose additional costs for data curation and retrieval.

The impact of these European policies on archaeological researchers and repositories cannot be easily traced, as the evaluation did not address archaeology specifically. However, what has been implemented follows the Commission's Recommendation on Access to and Preservation of Scientific Information (2012/417/EU) regarding open access to research publications and data and covers all disciplines, including archaeology. The measures taken following the Recommendation on Digitisation and Online Accessibility and Digital Preservation of Cultural Material (2011/711/EU) have also probably influenced the digitisation and access to collections of archaeological archives and museums.

The impact of the revised Directive on the Reuse of Public Sector Information in 2013 (Directive 2013/37/EU), which included publicly funded libraries, archives and museums, may have been limited, while the new Directive on Open Data and the Reuse of Public Sector Information (Directive (EU) 2019/1024) could have a greater effect concerning digital repositories. A question on the relevance of the Directive for archaeological repositories in the EU has been included in the survey (see Section 6.6.3).

The survey adopted a bottom-up approach by focusing on the policies and practices of digital archaeological repositories. While these may reflect higher level regulations, a bottom-up approach was chosen as it allows an evaluation of the extent to which the operational rules and practices of repositories conform to FAIR ideals and support for open access data. A reality check such as this can enable high-level institutions to reinforce or put in place regulations that bring current repository policies and practices closer to the ideal.

The ARIADNEplus and SEADDA initiatives support the FAIR and open data principles for publicly funded institutions and projects. They recognise, however, that improving the management and sharing of archaeological data needs to take account of the realities of existing practices. These are in general reasonable when one considers factors such as established rules and routines, limited resources, existing IPR/copyright, legacy technology and metadata, among others. The objective is not to impose some abstract criteria to become 'FAIRer' but to support changes in ingrained data-related practices so that the outcomes gradually align with the ideals of FAIR and open data.

The bottom-up survey approach was developed in this spirit: before giving recommendations and providing guidance to improve and possibly harmonise policies across digital archaeological repositories, we investigated current practices. Any recommendations and guidance can then better support repositories, having taken account of where they stand at present and their aspirations for further development.

The online survey addressed directors, managers and curators of digital archaeological repositories. The respondents included SEADDA and ARIADNEplus partners, representatives of other known repositories, as well as others identified during the survey preparation and dissemination, including those in the various regions of countries such as Belgium, the Länder in Germany, and the autonomous regions in Spain.

In addition registries of repositories were mined, including OpenDOAR (Directory of Open Access Repositories – subject: 'history and archaeology', re3data (Registry of Research Data Repositories, – 'ancient cultures', and ROAR (Registry of Open Access Repositories – 'archaeology' and 'history of civilization'. Registered university-based and other repositories often use these subject terms to indicate that they have some relevant content. However, such multi-domain repositories generally have little relevant content (e.g. some theses, articles, and presentations) and little, if any, archaeological data. Therefore only a few relevant repositories could be added to the list.

The final list contained 94 repository contacts. All were invited to help assess the current policies concerning access to and reuse of archaeological data, and to inform guidance on approaches to make archaeological data FAIR. The online questionnaire was developed by Geser (Salzburg Research Institute) and Massara (Central Institute for the Union Catalogue of Italian Libraries). It comprised 26 questions, many with the option to include multiple answers, and a free text field for further information and comments. It was implemented on the Microsoft Forms platform and tested by colleagues who work at repositories that are operative or currently being set up, and their suggestions for improvements were implemented.

The survey was open for responses from 17 June to 19 September 2021. During this period Massara e-mailed all 94 contacts, and the survey was also disseminated to all ARIADNEplus and SEADDA partners via their Basecamp team communication channel, requesting dissemination beyond the partnerships. Four contacts said that their organisation did not have a repository, others suggested that another person at their institution or a supporting organisation could respond.

In total we collected information about 60 repositories, 43 operative and 17 currently being set up, although a few respondents did not answer all questions. For seven repositories two respondents each provided information. In these cases the more detailed responses were used in the analysis but, where available, further information from the second respondent was added. Respondents were assured that their information would be treated in a confidential manner. Therefore, some responses in free text fields have been anonymised where the information makes it possible to identify the institution of the respondent. Taking the 94 directly invited contacts as the basis, the survey had a response rate of 64%. The full survey results, including the many comments and further information given by respondents in free text fields, are available in Geser (2021b).

There is no comprehensive overview of institutions that qualify as digital archaeological repositories. Therefore it is impossible to say whether the survey coverage is representative. Nonetheless, to the best of our knowledge it is the largest survey on policies and practices of repositories supporting a single discipline to date. With rich information covering 60 repositories our results provide insights that further research can build upon.

This section presents the survey results, including repository status (operative or being set up), the number per country, the types of organisations where the repositories are based, the responsibilities of survey respondents, how many members of staff work for the repositories, and the number of years for which they have been operative.

The survey gathered information about 60 repositories, 43 already operative and 17 currently being set up.

Table 1 gives an overview of the countries and the number of repositories for which completed questionnaires have been received. The responses provide information on one or more repositories located in most European countries as well as some in other countries.

| Countries | Repositories | Countries | Repositories |

|---|---|---|---|

| European countries | |||

| Austria | 3 | Poland | 3 |

| Belgium | 2 | Portugal | 4 |

| Bosnia & Herzegovina | 2 | Romania | 2 |

| Bulgaria | 2 | Serbia | 1 |

| Croatia | 2 | Slovakia | 2 |

| Cyprus | 1 | Slovenia | 1 |

| Czechia | 1 | Spain | 2 |

| Denmark | 1 | Sweden | 2 |

| Estonia | 1 | Switzerland | 2 |

| Finland | 1 | United Kingdom | 2 |

| France | 1 | Other countries | |

| Germany | 3 | Argentina | 1 |

| Greece | 3 | Canada | 1 |

| Hungary | 1 | Israel | 2 |

| Italy | 3 | Japan | 1 |

| Latvia | 1 | Turkey | 1 |

| Lithuania | 2 | United States | 1 |

| Malta | 1 | ||

| Netherlands | 1 | Total | 60 |

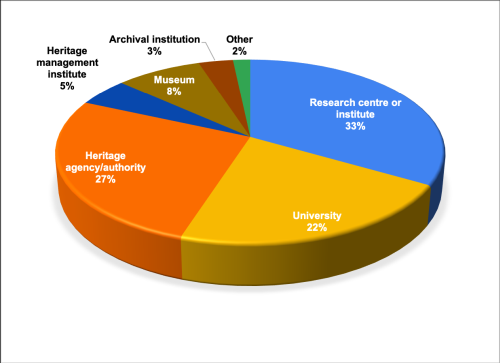

Table 2 (Figure 1) presents the distribution of types of organisation at which repositories are based or, in the case of repositories in preparation, will be based.

Most of the organisations are research centres or institutes (20), universities (13), and heritage agencies/authorities (16). The latter are governmental institutions (e.g. ministries of culture) or operating under them (e.g. heritage councils). Three organisations are heritage management institutes, i.e. organisations to which heritage authorities delegate operative tasks of heritage management. The sample of repositories also includes five based at museums, two at archival institutions, and one 'other', which was a national archaeological association.

| Research centre or institute | 20 |

| Heritage agency/authority | 16 |

| University | 13 |

| Museum | 5 |

| Heritage management institute | 3 |

| Archival institution | 2 |

| Other [an archaeological society] | 1 |

Table 3 (Figure 2) presents the distribution of repository-related responsibilities/tasks across survey respondents. In the questionnaire, a limited set of likely responsibilities were included as options, with the option to specify additional responsibilities or tasks. Most respondents are responsible for more than one task, often including project management, collections development, and digital archiving/curation. Twenty of the respondents are directors or deputy directors of repositories, of which five are also digital archivists/curators. Those responsible for IT systems management or user access services and support are less well represented.

All respondents selected at least one responsibility from the list. The free text field was used by some respondents to explain their main role or activity, for example: "Head repository manager", "Head of the data provider group" or "I manage the IT team that maintains IT services for the repository, but we also do a lot of other things".

| Director or Deputy Director | 20 |

| Digital archivist/curator | 26 |

| IT systems management | 16 |

| Project management | 33 |

| Collections development | 26 |

| User access services and support | 15 |

Respondents were asked how many members of staff work for the repository, including only those whose work relates mainly or in substantial part to the repository (Table 4; Figure 3). The majority of those who answered the question (55) said that the organisation that manages the repository has two such staff (17 respondents) or three to five (21 respondents). Only one member of staff was reported for four repositories; six, seven and ten for three repositories each, and fifteen staff for four repositories. The latter is a high number of people, indicating that more than one staff member work on tasks such as outreach, data acquisition and ingest, data curation, IT systems management, collections development, user services (deposition, access), project management, and overall repository management.

| Members of staff | Repositories |

|---|---|

| 1 | 4 |

| 2 | 17 |

| 3 | 5 |

| 4 | 9 |

| 5 | 7 |

| 6 | 3 |

| 7 | 3 |

| 10 | 3 |

| 15 | 4 |

Respondents from existing repositories (43) were asked how long the repository had been operative (Table 5; Figure 4). Of the respondents who answered the question (41), most said between 3 and 10 years (24 respondents). Only three repositories had been operative for 1-2 years, while 14 repositories had been running for over 10 years.

| 1-2 years | 3 |

| 3-5 years | 13 |

| 6-10 years | 11 |

| 11-15 years | 6 |

| 16-20 years | 5 |

| Over 20 years | 3 |

This section presents the responses to questions related to which archaeological data are or will be deposited, time until deposition after completion of the work, charge for deposition, embargo period, personal data protection, and long-term storage and preservation.

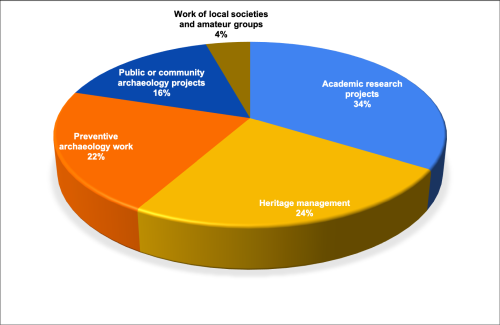

Respondents were asked what types of archaeological work are (or will be) deposited in their repositories. The question presented a list of five categories of work. Table 6 (Figure 5) shows the distribution of the categories selected across the 60 respondents.

These results are only indicative because the respondents were requested to select the two most important categories only, which 35 did and 25 did not. The request was thought to allow an easier identification of patterns in the data than if respondents could also include other but less important categories.

However, the results show that in our sample of repositories most contain (or will contain) results of academic research projects (47) and heritage management work (34) and/or preventive archaeology (30). In a closer analysis of combinations of data types, 10 contain all three categories, 15 contain both academic research and heritage management, and 9 both academic research and preventive archaeology. Only 13 respondents did not select the category academic research projects. This does not mean that most repositories are primarily academic repositories, rather that repositories of research institutions and heritage management institutions store results of different archaeological work.

| Academic research projects | 47 |

| Heritage management | 34 |

| Preventive archaeology work | 30 |

| Public or community archaeology projects | 22 |

| Work of local societies and amateur groups | 6 |

Looking at the 35 respondents who selected only two categories of archaeological work, the main pattern confirms this result. A majority of 24 chose academic research projects, most often together with results related to heritage management (13) or preventive archaeology (7). Three selected as the second category public or community archaeology projects, and only one work of local societies and amateur groups.

It is of particular note that the work of local societies and amateur groups, mentioned as an important category in total by six respondents, is present only where the results of academic research projects are also deposited. For public or community archaeology projects this is the case for 16 of the 22 mentions of this category.

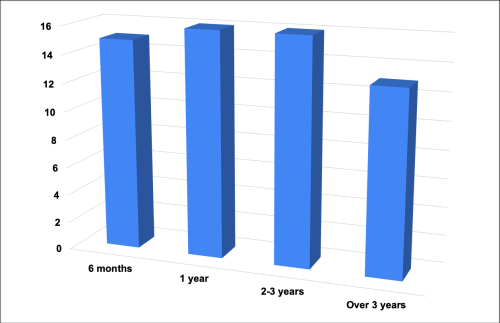

Respondents were asked, How long after the completion of the archaeological fieldwork is (will) data usually be provided to the repository?. The results indicate that for around half of projects data deposition takes place after one to three years (Figure 6). Where there was earlier deposition, respondents explained that this was generally mandatory documentation to be provided to the heritage authority or agency during the fieldwork.

In comments respondents described when different reports and data delivery are due. Specific comments included:

Where the heritage authority/agency does not provide a data repository, the data generally stay with the archaeologists who carried out the work.

Respondents were asked, Do depositors have to pay a deposit charge for the preservation of their data?. Of the 59 respondents who answered the question, 4 replied 'Yes' and 55 'No' (Figure 7).

Some respondents mentioned that a deposit charge is due where the data volume exceeds a certain limit or gave information on the pricing:

Respondents were asked, Can data depositors set an embargo period before their data are accessible?. All 60 respondents answered the question, 38 said 'Yes', 22 'No' (Figure 8).

Some respondents provided information about which data can be embargoed and the possible embargo period, which ranged from 6 months to 10 years, but with the average around 2-5 years. Specific comments included:

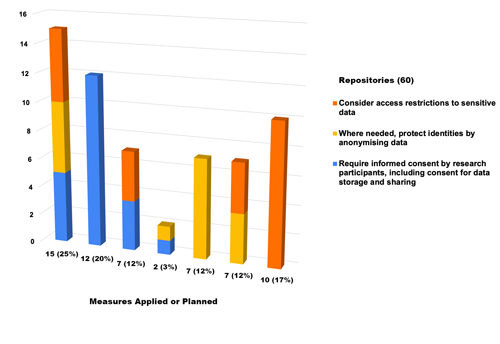

Respondents were asked, What measures does the repository apply concerning personal data related to or within deposited content?. Three answer options were predefined but respondents could also specify others or add further comments. Figure 9 shows the distribution of the predefined options selected across the 60 responses.

Fifteen respondents said that all three measures are being applied, while 12 indicated only informed consent, 7 only anonymisation, and 10 only access restrictions for sensitive data. Other respondents said that two of the three measures are being applied.

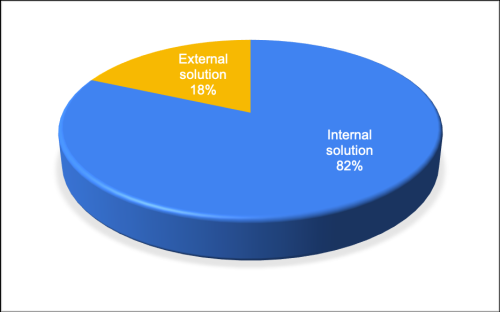

Respondents were asked, Does the repository have its own or an external solution for long-term storage and preservation of archived data?. All 60 respondents answered the question, 49 said that an internal solution is in place, 11 that an external solution is being used (Figure 10).

Several respondents provided further information, describing the setup of the data storage and preservation solution, including internal and external components (e.g. backup), or whether everything was provided externally. Comments included:

This section provides background on the FAIR principles and open access data, describes the survey approach for these topics, and presents the results.

Over the last few years, the FAIR data principles, published in 2016, have been adopted by research funders, institutes and researchers to promote the access to research data through data repositories and infrastructures. The FAIR data principles require "that all research objects should be Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable (FAIR) both for machines and for people" (Wilkinson et al. 2016).

The FAIR principles address important attributes of research data, for example, globally unique and persistent identifiers, rich metadata, use of domain vocabularies, registration in a searchable resource, and release with a clear data usage licence. The 15 principles are listed below:

To be Findable:

F1. (meta)data are assigned a globally unique and persistent identifier

F2. data are described with rich metadata (defined by R1 below)

F3. metadata clearly and explicitly include the identifier of the data it describes

F4. (meta)data are registered or indexed in a searchable resource

To be Accessible:

A1. (meta)data are retrievable by their identifier using a standardised communications protocol

A1.1. the protocol is free, open and universally implementable

A1.2. the protocol allows for an authentication and authorisation procedure, where necessary

A2. metadata are accessible, even when the data are no longer available

To be Interoperable:

I1. (meta)data use a formal, accessible, shared, and broadly applicable language for knowledge representation

I2. (meta)data uses vocabularies that follow FAIR principles

I3. (meta)data include qualified references to other (meta)data

To be Reusable:

R1. (meta)data are richly described with a plurality of accurate and relevant attributes

R1.1. (meta)data are released with a clear and accessible data usage licence

R1.2. (meta)data are associated with data provenance

R1.3. (meta)data meet domain relevant community standards

Source: Wilkinson et al. 2016.

Further commentary of the meaning of each principle can be found in the original FAIR data paper and subsequent publications (e.g. Boeckhout et al. 2018; Expert Group on FAIR Data 2018; GO FAIR; Mons et al. 2017). Our approach to questions concerning the application of the FAIR principles by repositories is explained in Section 6.4.

While reference to the FAIR principles has become almost obligatory within the international research data management community, wider knowledge of how to apply the principles cannot be assumed among either researchers or repositories.

In the annual Figshare 'State of Open Data' survey, the percentage of researchers who claimed to be familiar with FAIR increased from 15% in 2018 to 20% in 2020. Other respondents had heard of FAIR, but did not consider themselves familiar with the principles, or had never heard of the principles (Figshare 2018; 2019; 2020; Khodiyar 2021). David et al. (2020) warn that FAIRness literacy is the Achilles' heel of applying the principles, and propose that in order to train researchers in communities with low data-skills we need to improve the clarity of what the principles require in practice.

For this purpose, ARIADNEplus and SEADDA have promoted use of the FAIRify guidelines that were developed in the PARTHENOS project. The FAIRify guide (PARTHENOS 2018) provides 20 guidelines for making research data as reusable as possible based upon the FAIR principles. Each guideline has recommendations for both researchers and repositories, as it is recognised that different perspectives or priorities may apply to each case.

A growing demand for practical FAIR training is also visible. To help researchers and data managers to understand what is meant by the FAIR principles and how they can make their own datasets more FAIR, an online learning tool is available, FAIR-aware. Using the tool is the first step in the process of putting the FAIR principles into practice. It helps to assess knowledge of the FAIR principles, and aims to make researchers more aware of how making their datasets FAIR can increase their potential value and impact.

It should also be noted that to ensure data are born and kept FAIR, data management planning (DMP) is one of the first important steps a researcher should take, and training in DMP can help stimulate FAIR awareness. ARIADNEplus developed a DMP template specific for the archaeological community, which takes account of Open Science and FAIR principles as well as types of data, metadata, vocabularies and other standards of the community.

A better understanding of the FAIR principles by repository staff rather than researchers can be assumed, but the implementation of the principles is still often insufficient. Dunning et al. (2017) reviewed 37 very different repositories and databases. They found that for many FAIR facets less than half of the repositories/databases were compliant. This did not come as a surprise because, as the authors write:

"The 15 facets of the FAIR principles are all short sentences. Their brevity gives the impression that they are all items that can be checked off. However, our analysis shows that the FAIR principles are much trickier than this. Some facets appear to overlap (e.g. the plurality of attributes in R1 and rich metadata in F2). Some are vague (e.g. the qualified references of I3), others are open ended (the recursive request of I2 that '(meta)data use vocabularies that follow FAIR principles'), while others require interpretation from external parties (e.g. the domain relevant community standards of R4). Some appear to be technical in scope (A1, A2 and A3, for example) whereas others are more policy driven (the policy on the retention of metadata in A4)" (Dunning et al. 2017, 187).

Consequently, they identified many misconceptions of repositories related to the principles' definition and implementation, as did the survey of the Research Data Management Working Group of the Association of European Research Libraries (LIBER). This survey received responses from managers and technical staff of 32 repositories (Ivanović et al. 2019). An EOSC-NORDIC study of nearly 100 repositories using an automatic procedure to evaluate metadata FAIRness found considerable shortcomings (EOSC-NORDIC 2021).

Repositories that are certified as trustworthy data repositories based on the CoreTrustSeal criteria may be better off regarding compliance with the FAIR principles (Mokrane and Recker 2019; work in the FAIRsFAIR project aims to make the CoreTrustSeal more 'FAIRenabling', e.g. L'Hours et al. 2021). However, there are not many CoreTrustSeal certified repositories, either in Europe or worldwide. Such ARIADNEplus project partners include the Archaeology Data Service (UK), the Austrian Centre for Digital Humanities and Cultural Heritage, Data Archiving and Networked Services (Netherlands), and the Swedish National Data Service.

The Archaeology Data Service describes in detail the specific ways in which they ensure compliance with all aspects of FAIR. A comprehensive survey on the FAIRness of repositories would indeed require spelling out the FAIR principles and the different possible ways in which they could be met, and then asking staff whether any of these are implemented in their repositories.

The question of the FAIRness of repositories must necessarily consider the level of 'open access' they provide. The phrase 'open access' is often not explained well, which leads to misunderstanding. The matter is indeed quite difficult. In practice three levels of access can be distinguished:

Misunderstandings also surrounded the oft-used phrase that one can 'freely access' a repository, metadata, or data. Here 'freely' means that no restrictions apply on any of the three levels, but this is also understood as 'for free', i.e. that one does not have to pay for access. Advocates of strict open access require that the repository user should not have to pay anything.

The widely referenced 'Open Definition' of the Open Knowledge Foundation defines 'open' briefly as "Open means anyone can freely access, use, modify, and share for any purpose (subject, at most, to requirements that preserve provenance and openness)". Details are then given on criteria that should be fulfilled so that data, content or knowledge can be considered as open, especially that it should be shared under an open licence or in the public domain.

Licensing is also a key principle in FAIR, as R1.1. (meta)data are released with a clear and accessible data usage license. The main difference to open access (meta)data is that the FAIR principles do not imply that the data is 'open' or 'free' in the sense of uncontrolled and free of charge access and reuse.

As Mons et al. (2017, 52) explain "None of these principles necessitate data being 'open' or 'free'. They do, however, require clarity and transparency around the conditions governing access and reuse. As such, while FAIR data does not need to be open, in order to comply with the condition of reusability, FAIR data are required to have a clear, preferably machine readable, license".

They also highlight that the different approach of FAIR in this regard allows participation of data holders that otherwise could not be involved: "The transparent but controlled accessibility of data and services, as opposed to the ambiguous blanket-concept of 'open', allows the participation of a broad range of sectors – public and private – as well as genuine equal partnership with stakeholders in all societies around the world" (Mons et al. 2017).

The survey covered many different topics and therefore had to keep things simple. A comprehensive survey on the FAIRness of repositories would have to explain each of the 15 FAIR principles and the different ways in which a principle could be fulfilled, possibly distinguishing different degrees of FAIRness.

This is hardly possible in an online survey. Therefore, questions were set that covered key areas addressed by the FAIR principles and which could be answered by respondents who know how they are implemented at their repository. These questions concern (meta)data identifiers, metadata richness, vocabulary in use, (meta)data discovery (i.e. search interface and/or external search platform), and licensing. Technical questions (e.g. about communication protocols) and some specific metadata-related questions (e.g. formal knowledge representation or qualified references to other (meta)data) were avoided.

What the FAIR principles do not address are critical issues that repositories are arguably more interested in. For example, are there clear policies to support FAIR and open data policies? How should these be implemented in practice? How should data access be improved? Can we demonstrate that data are being reused? In addition to surveying some aspects of the FAIR principles, these additional areas were therefore included in the survey.

This section covers the survey results for FAIR-related questions concerning identifiers, metadata richness, vocabulary in use, data discovery, copyrights and licensing. Regarding data discovery, the survey addressed finding data both via the search interface of the repository and via external search platforms with which it shares metadata.

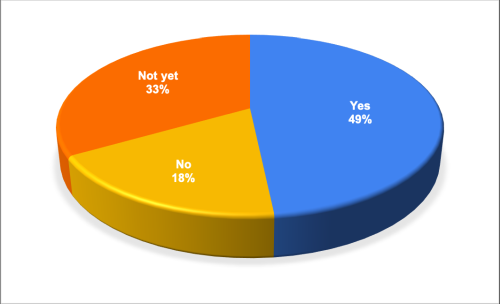

Respondents were asked (Figure 11), Are deposited data assigned globally unique and persistent identifiers (e.g. DOI, Handle, URN or other)? All 60 respondents answered the question, 29 said 'Yes', 11 'No', and 20 selected the additional option 'Not yet'. The answer option 'Not yet' was included as the survey also invited repositories to participate that are currently being set up and as yet may not have implemented procedures for assigning unique and persistent identifiers.

Comments mainly stated the type of identifier, with seven indicating DOIs, four Handles, and two Archival Resource Key (ARK) identifiers. Comments also described the challenges or approach to be adopted with implementing identifiers, including the cost, or relying on a parent body, such as a university library. One respondent reported that "The archive is maintained by the museum and there is no financial support for getting DOIs for all files. At present 1.18 million files are available online, but it is increasing rapidly".

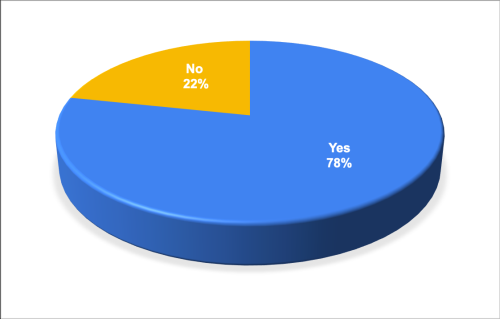

Respondents were asked, Are deposited data described with rich metadata, i.e. many descriptive attributes? All 60 respondents answered the question, 47 said 'Yes', 13 'No' (Figure 12).

Five stated that Dublin Core is being used, and several gave more detailed information, including as other metadata standards General International Standard Archival Description (ISAD(G), Encoded Archival Description (EAD) and Spectrum 5. One respondent noted that "All deposited metadata is related to the process, more than the results; i.e. what kind of research was undertaken, by whom, how much did it cost, where are the reports and files, where will the finds be deposited, what were previous steps and what are following steps, ⋯ But no things such as 'we excavated an Iron Age settlement'".

Respondents were asked, What vocabulary does the repository support? Five predefined answer options were given for kinds of vocabularies, concerning the user community (international, national, or only by the repository) and formalisation (e.g. following thesaurus standards, list of terms or keywords given by depositors). In a free text field respondents could also specify other vocabulary support or give comments. Table 7 (Figure 13) presents the distribution of the predefined options selected across the 60 respondents, who had the option to select multiple answers.

| Own standardised vocabulary (e.g. own thesaurus) | 35 |

| National vocabulary (e.g. thesaurus of a national authority or association) | 25 |

| Own list of terms | 25 |

| International vocabulary (e.g. Getty Art and Architecture Thesaurus) | 19 |

| Keywords given by depositors | 17 |

Nearly two-thirds of respondents (39 out of 60) said that their repository uses more than one vocabulary; of which 20 selected two, 17 three, and 2 even four of the predefined categories. These vocabularies can be used for the metadata records of single items (e.g. publications, fieldwork or laboratory reports) or records of project archives, possibly also for different types of content within them (e.g. various parts of an excavation archive).

Most repositories in the sample use their own standardised vocabulary (e.g. an internal thesaurus); nine out of 35 only used this. Where, in addition, other vocabularies are being used, this is often a national vocabulary (10), an internal list of terms (10), or both (5); some of these repositories also use an international vocabulary, or keywords given by depositors. Among the 25 repositories using a national vocabulary are the ten already mentioned who use it in addition to their own standardised vocabulary), and ten other cases. Three of these only use the national vocabulary, another six use an international vocabulary, and three of these also use keywords given by depositors. Five repositories use only an international vocabulary and two in addition their own list of terms or keywords given by depositors. Five repositories use their own list of terms and keywords given by depositors.

Several comments indicate use of the multilingual Getty Art and Architecture Thesaurus (AAT), particularly in mapping their own terms to equivalent ones in the AAT. Such mappings to a common vocabulary (thesaurus, gazetteer or other) support searches across different repositories, for example, in the ARIADNEplus network. One comment explains why an internal lists of terms, derived from user keywords, is being used: "Environmental archaeology covers many research domains (ecology, geology, archaeology,⋯) and so no list covers everything needed. We have taken a pragmatic approach of user keywords with periodic cleaning and harmonization. Mapping to international and national vocabularies will be undertaken in future, but will not be a core part of the database.".

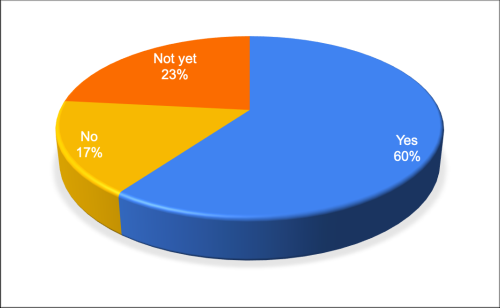

Respondents were asked, Does the repository provide a metadata search interface? All 60 respondents answered; 36 said 'Yes', 10 'No', and 14 'Not yet' (Figure 14). Seventeen respondents said that their repository is in preparation. The answers 'No' and 'Not yet' total 24; hence some repositories in operation do not have a metadata search interface, but other ways to navigate and browse their collections. Further information provided by respondents included links to the search interface, and one respondent wrote that there is more than one interface allowing search of different parts of the repository database. Other comments concerned the status of the interface development, e.g. "Under development – Alpha version" or "This is planned in the database migration project". Comments also explained the metadata or metadata model to be adopted for searches, e.g. "For basic metadata/descriptive/links, not technical metadata" or "CIDOC CRM syntax will be employed".

Respondents were asked, Does the repository make metadata available to external search platforms/engines? All 60 respondents answered; 25 said 'Yes', 26 'No', and 9 'Don't know' (Figure 15). Many respondents said that their repository does not share metadata with external search platforms or that they did not know. These include 17 repositories currently being set up and 18 in operation. It appears that some of the latter do not see a need to make their holdings findable via external search platforms or for some other reason cannot do this. There can be many reasons; for example, the user base of the repository is well known and not expected to increase, lack of a suitable external platform, or a legacy metadata management system that does not support metadata harvesting. Respondents gave further information about platforms to which metadata is being provided, including both ARIADNE and Europeana, and others mentioned the methods employed, including OAI-PMH, API feeds, or via a SPARQL endpoint.

The FAIR data principles do not address copyright but it is important to know who holds copyright and therefore can license works that have been deposited. Respondents were asked, What is your organisation's policy on copyrights in deposited archaeological works (e.g. reports, data)? Four answer options were predefined and respondents could specify others or add further comments. Table 8 (Figure 16) shows the distribution of the selected predefined options across the 60 responses.

| The organisation holds copyright in work created by employees | 36 |

| Copyright in most work is held by depositors | 26 |

| The organisation holds copyright in work commissioned by third parties | 21 |

| Copyright in work of staff members is solely held by them | 15 |

Here two types of repositories and copyright policies can be distinguished:

This is the general pattern, but type (a) repositories, those mainly for external depositors, can also contain works of their own staff or commissioned works, and type (b) institutional repositories can sometimes contain works by external researchers. Many organisations hold copyright in works created by their own staff (36), while at others the copyright is held solely by the researchers (15). Only in six cases did the organisation hold copyright for some works and the researchers for others.

Several respondents provided additional information, including:

While the previous question concerned who holds copyright in deposited archaeological research results, the survey also addressed the important related question about the conditions set for accessing the work and the licences being applied. Respondents were asked, Which licence frameworks does the repository support? They could select multiple answers from seven predefined options and add information in a free text field. Table 9 (Figure 17) shows the distribution of the predefined options selected across the 60 responses.

| Public Domain Dedication, e.g. CC0, PDDL or other | 16 |

| Users must only give attribution, e.g. CC-BY, ODC-BY or other | 22 |

| Users must share new work under the same licence, e.g. CC-BY-SA, ODC-ODbL or other | 12 |

| Do not allow commercial use, e.g. CC-BY-NC or other | 17 |

| Do not allow derivative works, e.g. CC-BY-ND or other. | 9 |

| Own terms and conditions, incl. some restrictions e.g. non-commercial, no derivatives or other | 29 |

| All or most works are fully copyright protected | 20 |

Closer analysis of the responses shows that four broad approaches to licensing are represented in our sample:

One respondent commented, "We have a legal right to publish the reports, but this right does not stipulate reuse. On the other hand, since most of the data can be seen as scientific data, this might make little difference", while another said "For commercial users we prefer to give access on the base of a specific written request in order to know better what are the needs and purposes of the reuse of the data".

The responses to questions on the 'FAIRness' of archaeological repositories provide valuable insights into current practices regarding requirements for data discovery, access, and use. However, the FAIR principles do not cover some arguably more important issues. These include questions concerning open data access policies (e.g. established or missing) and control of access (e.g. sensitive data, access only for legitimate users), which are addressed in this section. Also addressed is the question of how to improve data access. For this question the FAIR principles give general recommendations, while our survey was also interested in what the responding repositories see as necessary to improve. Moreover, we also addressed the critical issue of whether repositories can demonstrate not only increasing access to the data they hold, as found during the COVID-19 crisis, but also that it is being reused.

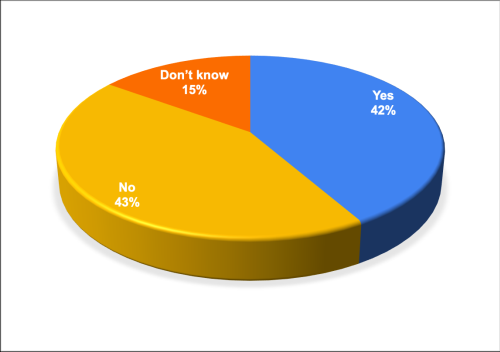

Respondents were asked What would help the repository most to support open data access and reuse policies? Seven options were predefined, and respondents could also specify others or add further comments. Table 10 (Figure 18) shows the distribution of the predefined options selected by 56 respondents.

| Heritage regulations to set such policies/rules | 39 |

| Clear guidelines of heritage authorities | 36 |

| Research funding bodies to set such policies/rules | 21 |

| Clear guidelines of research funding bodies | 15 |

| Defined internal/institutional rules to follow | 23 |

| Training of repository staff to support new policies | 28 |

| Overcome barriers of users to deposit open and reusable data | 29 |

Most selected two or more options. Where only one option was chosen this was heritage regulations to set policies/rules (9%), clear guidelines by heritage authorities (2%), and defined internal/institutional rules to follow (2%). Heritage regulations to set policies/rules (20%) and clear guidelines by heritage authorities (19%) were the main help needed to support open data access and reuse.

Next came the challenge of overcoming barriers to deposit open and reusable data (15%), including concerns about open licensing and that data might be misused. Respondents also considered training of staff to support new policies on open/FAIR data as important (15%).

Although policies/rules and clear guidelines from research funding bodies appear to be of less importance, this is perhaps because there are not many academic repositories in our sample. Repositories that serve both academic and preventive archaeology considered heritage regulations and the guidelines of heritage authorities to be more important than policies and guidelines of research funding bodies.

This question was among those that received most comments by respondents. Obviously, the question of how to support open data access and reuse policies is very important for repositories. Respondents stressed the importance of heritage regulations, raising awareness and good practices. Furthermore, training was considered as important for both researchers and repository staff, and appropriate technical systems could do much to support open data access and reuse policies. Respondents also thought the survey results could help, for example one said, "I wait for the results to improve the management of our repository".

Among those stressing the need for changes in legal regulations or institutional guidelines, comments included:

Other respondents commented on the need for increased awareness, knowledge and training, noting that what was needed was:

Finally, the need for more trained staff was highlighted by several respondents:

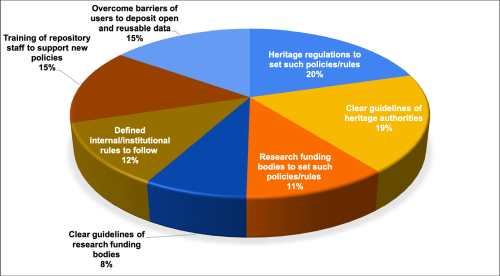

Respondents were also asked, Is there national legislation in your country that determines which documentation of archaeological investigations and interventions has to be provided to a repository? Unlike the previous question, this one concerned regulations about the specific content of archaeological documentation. All 60 respondents answered the question, 36 said 'Yes', 24 'No' (Figure 19).

Many respondents gave information on whether there are national regulations for archaeological documentation or an archaeological repository in their country:

In some cases, however, existing regulations or guidelines are perceived as insufficient:

In 2019 the EU Directive on the Reuse of Public Sector Information (Directive 2003/98/EC and amendments) was replaced by the Directive (EU) 2019/1024 on Open Data and the Reuse of Public Sector Information, also called the Open Data Directive. Article 10 of the Open Data Directive aims to make research data funded, collected or generated by public sector bodies openly accessible and reusable (see Section 2.3).

The Directive addresses governmental bodies, bodies governed by public law, and organisations owned or governed by them. This wide spectrum of public sector bodies/organisations includes governmental heritage authorities at all levels (national/regional/local), heritage agencies or associations established by public law, research-intensive public museums and other heritage institutions.

The survey question on the Open Data Directive was introduced by the following information: 'The Directive (EU) 2019/1024 on Open Data and the Reuse of Public Sector Information, among other points, states that Member States have to establish policies and actions "aiming at making publicly funded research data openly available ('open access policies') following the principle of 'open by default' and compatible with FAIR principles". Member States have to implement this in the national law by 16 July 2021'.

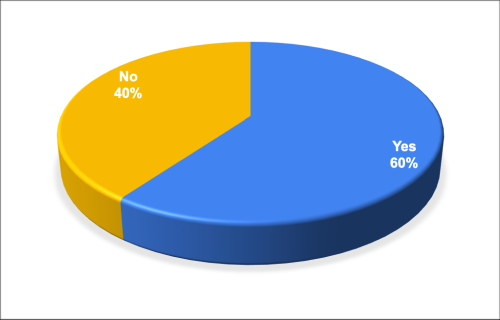

Respondents were asked, If your repository is located in the European Union, does it fall under the Directive (EU) 2019/1024?. Forty-six respondents answered the question of which 21 said 'Yes', 5 'No', and 20 'Don't know' (Figure 20).

A surprising number of respondents were clear whether the regulations of the Directive applied to their repository. We expected more 'Don't know', but the fact that there were still 20 respondents who said this suggests that there is a need for more support to enable repositories to understand whether the Directive applies and the consequences where this is the case.

Among the comments, two respondents stated that their repository is not concerned because it is already an open access repository. One respondent said the question must be addressed at the governmental level (not the heritage agency), and another that it depends on who has funded the research. Other responses concerned lack of support for repositories.

Respondents were asked How can people access data in the repository? and could select from five predefined answers. Table 11 (Figure 21) presents the answers across all 60 respondents.

| Open access, no registration required | 35 |

| Open access, but registration required | 8 |

| Legitimate registered users only (e.g. archaeologists, cultural heritage managers…) | 18 |

| Access based on request (permission to be granted) | 26 |

| Internal staff only | 9 |

A closer analysis revealed that three broad approaches are present:

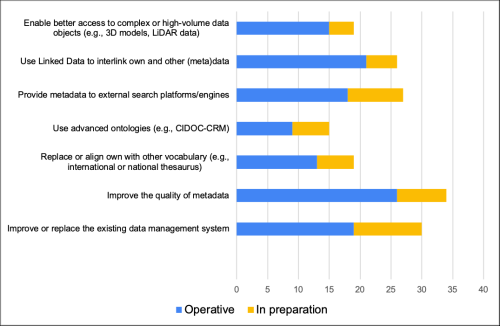

Respondents were asked, What would help the repository most for improving data access? Seven options were predefined, and respondents were asked to select a maximum of three most important options for their repository. Table 12 (Figure 22) shows the distribution of the predefined options selected by all 60 respondents, for repositories in preparation (28%), and operational ones (72%).

It proved difficult to identify clear patterns as the respondents selected many different combinations of answers and did not always follow the request for a maximum of three. However, four options for improving data access were more frequently selected. These were 'Improve or replace the existing data management system', 'Improve the quality of metadata', 'Provide metadata to external search platforms/engines' and 'Use Linked Data to interlink own and other (meta)data'.

The responses for repositories in preparation and those for existing ones were analysed separately. Obviously, these have some different needs that surfaced in the analysis.

| All (60) | In prep. (17) | Operative (43) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Improve or replace the existing data management system | 30 | 11 | 19 |

| Improve the quality of metadata | 34 | 8 | 26 |

| Replace or align own with other vocabulary (e.g. international or national thesaurus) | 19 | 6 | 13 |

| Use advanced ontologies (e.g. CIDOC-CRM) | 15 | 6 | 9 |

| Provide metadata to external search platforms/engines | 27 | 9 | 18 |

| Use Linked Data to interlink own and other (meta)data | 26 | 5 | 21 |

| Enable better access to complex or high-volume data objects (e.g. 3D models, LiDAR data) | 19 | 4 | 15 |

Repositories in preparation often wanted to improve their data management system (11). They also wanted to align their own vocabulary with another (e.g. international or national thesaurus) and/or use advanced ontologies (e.g. CIDOC-CRM) more often than existing repositories. Respondents who were satisfied with their data management and vocabulary wanted their data to be found by providing metadata to external search platforms and possibly to interlink their own and other (meta)data using a Linked Data approach.

In the responses from operational repositories three priorities could be identified. Among those who wanted to improve or replace their existing data management system (19), for nine the main reason appeared to be enabling better access to complex or high-volume data objects (e.g. 3D models, LiDAR data). This group of repositories had no other shared priority regarding additional ways of improving access to data. Another seven repositories shared the priority to improve metadata quality and to replace or align their own vocabulary with others. Furthermore, a group of repositories shared the priority to provide metadata to external search platforms and possibly to interlink their own and other (meta)data using a Linked Data approach. One respondent noted that "Adding chronological and/or typological metadata would be interesting, but the general consensus is that this would be a considerable amount of work that submitting archaeologists (a commercial sector) are not able to carry out".

For many repositories, it is important to collect and analyse data access statistics in order to report usage and identify where access procedures could be improved. For some repositories, it is crucial to be able to present statistics for data access that confirm demand, for example, when they must apply for funding. Where repositories support legal regulations (e.g. a repository of a heritage authority) or are mainly for staff and affiliated researchers the level of access is not as important.

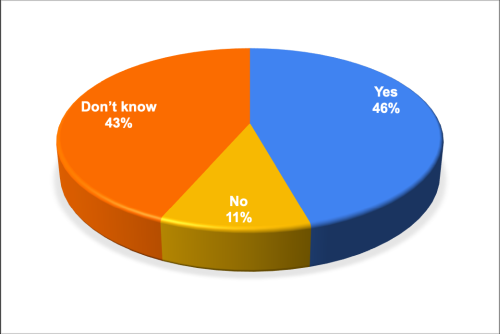

Respondents were asked, Does your organisation collect and analyse repository access data? and of 56 responses 27 said 'Yes' and 29 'No' (Figure 23). There is perhaps more work to be done on breaking this down, and on comparing methods of measuring data access.

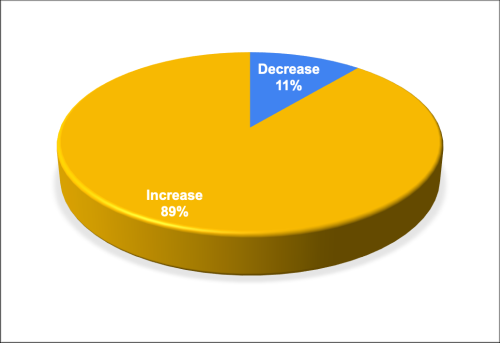

The 27 respondents who said that their organisation collects and analyses repository access data were also asked if there has been an increase or decrease of access during the COVID-19 pandemic. Twenty-four respondents said that overall there was an increase, only three a decrease (Figure 24).

Respondents were also asked if they could give an estimate or other related information. Among the 24 respondents who reported increased access, the percentage was a modest 5% for two, but five reported increases of 25-55%, and two even of 100% and above. Respondents were not asked for possible reasons for the change but it seems likely that with libraries, museums and archives closed researchers increasing relied on online resources, and that there may have been a permanent change in the pattern of researcher access. A recent study in the UK has also observed that as they closed their doors to visitors many museums made efforts to provide access to their collections online (Richards et al. 2022).

Reuse of data archived in accessible digital repositories is a very important topic in the data management community. While data access figures are good to have, being able to show significant data reuse for new research and other purposes can demonstrate even more effectively that funds for data preservation and access are well invested. For funders of data repositories, it is the clearest indication of a return on investment.

Data shared by others can be reused for different purposes, e.g. inclusion in a research dataset or community database, use for comparison, as test data, etc. (Geser 2019, 50-58; Huggett 2018; see also the ongoing research and discussion in SEADDA 2020).

However, for repositories data reuse is difficult to demonstrate, because if there is reuse it generally takes place outside of what they can easily track and measure. Therefore, some repositories actively scan the literature of fields of research they serve for mentions of reuse of the data they hold (Cousijn and Lammey 2018).

In recent years infrastructure and processes for identifying data citation in publications have been implemented, particularly DataCite, but also Crossref, Scholix (Scholarly Link eXchange) and others. But these capture only a fraction of the use of shared data for several reasons, which include that many repositories do not assign DataCite DOIs, publishers of journals and proceedings do not request proper data citation, or that researchers do not follow citation standards or only informally acknowledge data reuse.

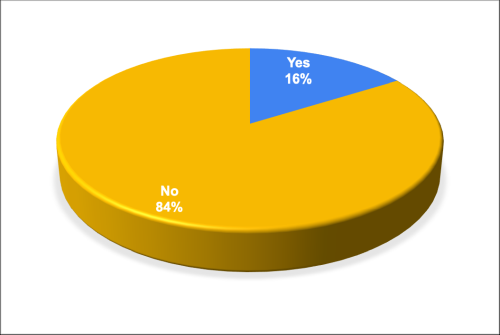

The survey asked, Does the repository collect information about data reuse (e.g. references in publications or other sources)? Fifty-six respondents answered the question: 9 said 'Yes'; 47 'No' (Figure 25).

Most comments noted that collecting information about data reuse is difficult and not very successful:

In this final section we summarise the conclusions of the survey results and make some suggestions for initiatives aimed to support FAIR data, data policies, and to improve data access.

Analysis of the responses for repositories in preparation (17) and in operation (43) separately showed some specific needs. For example:

The results show that repositories could greatly benefit from advice and support in several respects.

Repositories also need advice and possibly support regarding the collection and analysis of information about data access and reuse:

Nonetheless, it is encouraging for the open/FAIR data agenda that 24 of the 27 repositories (89%) that analyse data access reported that during the COVID-19 pandemic overall there was increased access, with increases ranging from 5% to over 100%. It seems likely that the COVID-19 crisis made archaeologists more aware of the importance of publicly shared data, data repositories and discovery and access services (see also Geser 2021a).

Overall, the survey has revealed tremendous variability in data management policies and practices across the countries surveyed. This is hardly surprising given that we received responses from 35 countries, and the same situation is also reflected in the national reviews in the SEADDA State of the Art volume (Jakobsson et al. 2021). Some 'early adopters' are relatively well advanced, but other countries have only recently recognised the need to develop repositories for archaeological data and capacity is still limited. Nonetheless, among the communities surveyed there was at least an awareness of the need for improvements and a willingness to undertake them. There would certainly be value in re-running the survey at a later date, as this is a rapidly changing field. While we have identified key areas for change, and it is clear that some of that can be driven 'bottom-up' by researchers and repository staff and networks such as SEADDA, it is also clear that funders and heritage agencies need to provide more guidance and regulations, and that the development of a network of repositories needs to be properly resourced. Finally, we also conclude that while there is growing awareness of the FAIR principles there is a need for practical guidance for best practice for implementation in a domain-specific context, which must be provided by those working within the discipline.

This publication has been funded by the COST Action SEADDA, and it aligns with the goal of SEADDA Working Group 3 to review current international best practice guidance, providing recommendations for expansion and improvement where needed. The survey it reports was carried out under the auspices of ARIADNEplus. The authors would like to express their thanks to all survey respondents. Julian Richards would also like to thank Hella Hollander for her contribution to the article.

ARIADNEplus is a project that has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 823914. The SEADDA COST Action (18128) is funded by the COST Association, also under the Horizon 2020 programme. Nonetheless, the views and opinions expressed here are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.