Cite this as: Ingrey, L., Duffy, SM., Bates, M., Shaw, A. and Pope, M. 2023 On the Discovery of a Late Acheulean 'Giant' Handaxe from the Maritime Academy, Frindsbury, Kent, Internet Archaeology 61. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.61.6

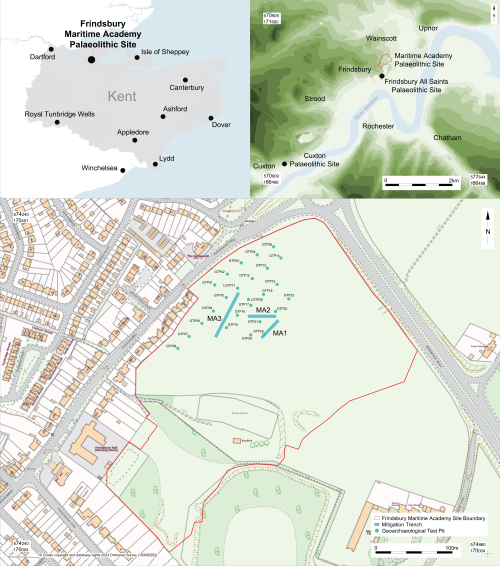

Starting in the spring of 2021, a programme of planned archaeological evaluation and subsequent mitigation was undertaken by Archaeology South-East, UCL Institute of Archaeology, at Manor Farm, Frindsbury, Kent (NGR: 574596 170317; Figure 1). This work was commissioned by Bowmer and Kirkland on behalf of the Department for Education ahead of construction of a new school, Maritime Academy, which has given its name to this new Palaeolithic site.

During the course of this fieldwork, Palaeolithic archaeology in the form of stone artefacts were encountered within a body of fluvial sediments, considered likely to relate to a Middle Pleistocene tributary of the River Medway. Here we report on a single artefact, a very large flint cutting tool, or handaxe, which is currently the third largest known to be found in Britain. The size of the handaxe and its distinctive symmetrical elongated tapering tip is typical of a type of handaxe known as a ficron. Similar tools are known from the Medway Valley and across southern England. The implications of these specific handaxe forms are uncertain. They may have had a specialised function in early human society, or relate to specific human groups, or even human species, expressing distinctive cultural identities during a defined period of the Pleistocene. Analysis of this tool as part of the wider artefact assemblages and scientific datasets could provide important new insights into the age and behavioural significance of these enigmatic artefacts. In this article we describe the tool and the context of its discovery. We also share a digital dataset recording the precise form of the tool and high-resolution photographic capture of its surface. We present the Maritime Academy handaxe as a new, culturally significant artefact from the Medway river catchment, a landscape that is already established in the British Palaeolithic as important for understanding early human cultural dynamics in the late Middle Pleistocene.

Ahead of construction of the new school, a programme of archaeological investigations was carried out. As Quaternary deposits had previously been mapped by the BGS at the site (BGS 2023), these works included a programme of geoarchaeological test pitting (Lincoln 2020). This initial stage of investigation proved Pleistocene fluvial deposits and colluvial sediments (Head) to be preserved over at least part of the site and that the fluvial deposits contained Palaeolithic artefacts.

On the basis of these results, further test pitting (Figure 1) was undertaken to better map and carry out a more focused archaeological assessment of the Pleistocene deposits (Ingrey et al. 2021). This more detailed assessment showed that Pleistocene fluvial and Head deposits were present across a large area of the site. Furthermore, the construction design for the northern part of the site covered by this article showed that some areas of Pleistocene deposits would be affected by proposed landscaping. A programme of targeted mitigation was therefore developed for the area of Pleistocene fluvial deposits, comprising three stepped trenches located on the areas of impact. Designated Mitigation Areas 1 to 3 (MA1-3), these were excavated either to the base of the proposed impact or to the base of the Quaternary sequence where possible. This mitigation response allowed for the recording of deposits, sampling for dating and palaeoenvironmental evidence, and for the recovery of any archaeological remains within these areas. The find reported on here relates to a discovery made during the excavation of Mitigation Area 3 (MA3), located in the north-western part of the site (Figure 1).

The solid geology for the entire site is Cretaceous Upper Chalk, overlain across much of the site by Palaeogene Thanet Formation sands and clays. Investigations showed the surface of the Upper Chalk to have undergone extensive solution, with the formation of both localised solution pipes and larger doline structures, which offered capture points for the preservation of the Thanet Formation sands and, more locally, Pleistocene deposits. At the contact between the Upper Chalk and the Thanet Formation the 'Bullhead' flint beds were frequently encountered, presenting as a layer of weathered and mineral-stained flint cobbles and pebbles formed during the Palaeogene. Pleistocene fluvial deposits had been locally subjected to significant deformation owing to solution of the underlying chalk. However, within the north-western area of the site where MA3 was located the fluvial deposits were present in channels and appeared to have undergone relatively minimal deformation. The Pleistocene fluvial deposits comprised moderately to well-sorted gravels in a matrix of sand and clay in channels incised into the Thanet Formation and overlain by Pleistocene Head. The channels were discrete and intercutting, each one up to 20m wide and extending up to 3m below ground level. The deposits consisted of up to 90% well-rounded to sub-rounded flint pebbles, largely reworked from Palaeogene deposits but containing occasional weathered nodules of flint from both the 'Bullhead' and Upper Chalk. Within the fluvial gravels were beds of finer grained sands, which were frequently finely bedded or laminated. Overall, the fluvial deposits appeared to relate to a series of episodes consisting of relatively high-energy deposition by a braided river system, with periods of lower energy deposition. This could relate to deposition on the inner banks of meanders and within cut-offs associated with anatomising channels, reflecting localised changes in depositional regime over time.

The base of the fluvial deposits was at approximately 27m OD. This terrace, from a small west bank tributary of the Medway, is mapped by the BGS as 'River Terrace Deposits, 3'. Correlation with the main Medway terraces is difficult. On altitudinal criteria these deposits would correlate with the Shakespeare Gravel (Bridgland 2003; Wenban-Smith et al. 2007) and would be ascribed to MIS 12/11/10. However, as Bates et al. (2017) have shown, major problems exist with the Bridgland model relating to the lower Medway. Fossiliferous interglacial deposits are present beneath the modern marsh surface at Allhallows that date to MIS 9, at altitudes at least 15m lower than predicted by Bridgland's work; consequently it appears overly simplistic to use altitude alone as a method for correlation in the Medway estuary area. On this basis no specific correlation has been attempted at this time, but a late Middle Pleistocene age is considered highly probable given that at least two morphologically distinct terraces are mapped in the area at lower elevations.

Palaeolithic stone artefacts, which will be reported on in due course, were recovered during each stage of investigation and were present at low densities throughout the fluvial deposits. In all cases artefacts have undergone only minimal abrasion and are not likely to have been extensively reworked. Among the artefacts were several handaxes recovered directly from the fluvial deposits. The handaxes include two very large or 'Giant handaxes'. These are both 'ficrons' with long and finely worked tips, and much thicker and more crudely worked butts. The first, Registered Find (RF) 50, at 230mm in length, although missing its tip, was recovered from a sand unit at the surface of the fluvial deposits. This was in an area that had been stripped to facilitate an excavation of later archaeology and was present within deposits just below the topsoil. Further excavation in the area showed the deposits here to have been mostly eroded but locally preserved within a solution feature that had deformed the underlying Thanet Formation and trapped the Pleistocene fluvial deposits. However, the most significant find and subject of this article was a second, even longer, handaxe (RF 53) at 296mm in length, which is discussed in greater detail below.

This very large handaxe (RF 53) was encountered while excavating Mitigation Area 3, a long stepped trench in the north-west of the site. The 50m long trench was positioned in an area of extensive fluvial deposits that would be affected by the development and was stepped to a depth of up to 3m. This trench was carefully excavated by machine in spits of no more than 5cm, with frequent samples of deposits comprising 30% of the total volume. Each sample was either dry sieved or, in the case of more clayey deposits, sifted through for artefacts on site. Following the removal of each spit, the trench was entered and the surface trowelled in order to search for archaeological remains.

This handaxe was encountered in a unit of weakly bedded sands and gravels comprised of moderately sorted very well-rounded to sub-rounded flint clasts, averaging 30mm in size, and iron-stained coarse sand with clay. The artefact was recovered at 1.2m below ground level, 28.8m OD. An illustration of the section and position of the artefact within the sequence of deposits can be seen in Figure 2. Careful hand excavation within the immediate area, following the discovery of the large handaxe, did not produce any further artefacts. On the basis of the minimally abraded nature of the artefact, and the fact that it was much larger than any of the other clasts within this part of the channel, we consider it likely to have been recovered from its primary depositional context and have been subjected only to short-distance transport, if at all.

The handaxe was recorded using photogrammetry in order to generate a dataset for use by other researchers, and by using established protocols for the recording of key metrics, technology and condition in order to provide a useful description. The methodologies employed are described below.

Multiple innovative digital techniques have been developed to study lithic artefacts (e.g. Olson et al. 2014; Bennett 2021; Caricola et al. 2018; Grosman et al. 2011; Grosman 2022; García-Medrano et al. 2023). Based on its flexibility and relative affordability, multi-image photogrammetry has become an increasingly useful analytical tool within archaeology (Magnani et al. 2020) with Close-Range Photogrammetry being used for lithic analysis (e.g. Caricola et al. 2018; Porter et al. 2016; Porter 2019; Collins et al. 2019; Bennett 2021; Timbrell et al. 2022).

The imaging approach entails capturing a set of overlapping digital photographs of the subject, which are processed with specialised software in order to produce 3D geometry. While it is possible to generate 3D geometry with image overlap of 60%, a much higher overlap of content captured between adjacent images (e.g. Guidi et al. 2020 and Iglhaut et al. 2019 suggest 80% overlap is optimal) and an integration of images taken from both vertical and oblique angles (Sadeq 2019) is optimal for photogrammetric capture and facilitates much finer detail in the final product.

Close-Range Photogrammetry was selected as the capture method with Metashape by Agisoft used for processing. Owing to the size and relative complexity of the shape of the handaxe, it was necessary to photograph it using multiple recording set-ups/arrangements that allowed recording in the round, in effect creating a virtual imaging dome around the object (approximately 650 images were captured).

In the first phase of processing, the photographs were aligned resulting in the production of a sparse point cloud, which was then refined using various optimisation tools, improving the accuracy of the camera alignment and thus the final 3D model. In the next stage, a dense point cloud was produced, which was used as the framework for the generation of a mesh in the following phase of processing. Finally, colour information from the image set is drawn upon in order to texture the model.

Coded targets were included during image capture and referred to during processing in order to test accuracy and allow scaling of the resulting 3D data (control scale bar error calculated at .000236m).

Known distances between reference points were also added during processing in order to scale the model and allow future measurements to be taken from the model for analysis. This phase allowed further examination of accuracy of the model. (In this case, the scale bar error was calculated to be 0.00026m.)

The metrics of the 3D model were further verified by taking measurements of various surface features of the handaxe with digital callipers and comparing to the measurements of the same features of the 3D model to confirm accuracy.

Outputs from this work include a 3D model, which has been optimised for dissemination on SketchFab, and a higher resolution model with a RAW image set available at https://doi.org/10.5522/04/c.6673061). Furthermore, high-resolution ortho imagery can be generated from the existing dataset, allowing flexible/unlimited positioning of the handaxe.

The handaxe was subjected to basic metrical analysis in order to acquire the seven key metrical measurements established by Roe (1967; 1968) and McNabb (2022). They provide a simple way of capturing handaxe dimensions, which allow its shape to be compared easily with vast bodies of published handaxe data for Britain and beyond. The measurements were captured using callipers including, given the size of the tool, a set borrowed from an archaeozoologist and more commonly used for measuring long bone elements from large mammalian fauna. Technology, morphology and condition was described with reference to the terminology described by Roe (1968), Wymer (1968), Singer et al. (1973) Scott (2011), and White (1996).

The artefact (Figure 3) is a bifacially worked Large Cutting Tool (LCT) or handaxe. It is a formally worked tool with a clearly defined and more intensively worked tip and a less refined base, or butt. The handaxe has a maximum longitudinal dimension of 29.6cm and a maximum width, at 7.4cm from the butt, of 11.3cm. Table 1 gives the full set of measurements.

The handaxe is manufactured on flint that appears, on the basis of a small amount of cortex retained on the butt, to be from a minimally weathered, elongated flint nodule. This is significant as other flint sources noted within fluvial gravels at the site, and which would have been both present in the landscape and from which it would be possible to make a bifacial tool, include large nodules of 'Bullhead' Flint from the base of the Thanet Formation, tabular flint slabs and fluvially weathered flint clasts ranging in size from pebble to small-boulder.

The condition of the handaxe was relatively fresh, suggesting minimal fluvial transport or abrasion. However, the condition of the tool was not uniform; Face 1 of the artefact, shown in image (a) on Figure 3 scored 1 (slight abrasion) across its surface on Singer et al.'s 1973 abrasion scale. This compares to Face 2 of the tool, shown in image (c) on Figure 3, which showed slightly more abrasion (scoring 1-2, slight to moderate abrasion). While the artefact was unpatinated, it did show variable staining, with Face 2 showing a pale greyish-pink colouring towards its tip, grading to a yellow-brown staining towards the butt. Face 1 was relatively less stained except for a light yellowish-brown staining towards the butt. Taken together it could be that this handaxe had spent some time lying on a surface with its Face 2 uppermost, exposed to very light abrasion and staining, maybe from low energy fluvial action. The handaxe shows some ancient edge damage, most likely from collision with small clasts, as well as a break resulting from its discovery during mechanical excavation.

| Metric | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Wt | Weight in grams | 1645 |

| L | Maximum length in millimetres | 296 |

| B | Maximum breadth in millimetres | 113 |

| Th | Maximum thickness in millimetres | 70 |

| B1 | Breadth at 20% of the length from the tip end in millimetres | 48 |

| B2 | Breadth at 20% of the length from the butt end in millimetres | 111 |

| L1 | Distance from butt to point of maximum breadth in millimetres | 74 |

| Th1 | Thickness at 20% of the length from the tip end in millimetres | 22 |

Typologically the handaxe exhibits a very clear 'ficron' form, which would be classified as Type M under Wymer's (1968) scheme. As viewed in Figure 3, the lower part of the tool, the butt, is relatively globular and, as evidenced by retained cortex from the original nodule, was not extensively reduced. In contrast, the upper part of the tool, the tip, has been extensively and carefully worked using a soft hammer to produce an elongated, converging point, with relatively straight and symmetrical sides. The transition from the butt to the tip evidences a shallow concave profile. The refined tip extends to 14.5cm down the tool's long axis, comprising very close to half the tool's length. While the tip does not exhibit a clear, bold tranchet or lateral sharpening removals, it has been finely worked and has a small transverse sharpening flake detached from its extremity. The uppermost tip of the tool would have been extremely sharp when initially made. The tool exhibits a good degree of symmetry both in plan and profile, with no edge twist evident.

There has been a recent resurgence in interest in the British record for 'Giant' handaxes, in terms of their function and cultural significance, and they have recently been discussed in detail by Dale (2022) who focused on their significance as cultural phenomena, associated in some cases with sites of an MIS 9 age. As part of his research, Dale was able to update R.J. MacRae's (1987) publication of 'The Great Giant Handaxe Stakes', a humorous look at the line up in the 'race' of the longest handaxes in Britain. Several new entrants have come along since MacRae's race card was compiled and the form of the current (known) top ten can be seen in Table 2. While the largest Furze Platt handaxe still maintains a healthy lead, it was joined at the top of the field with the discovery of the Cuxton ficron (Wenban-Smith 2004; Wenban-Smith et al. 2007). The larger of the two ficrons from Maritime Academy, which we have published here and added to the list, constitutes the third largest found in Britain at the time of writing.

| Artefact, type and date of discovery | Length (mm) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Furze Platt. Point. 1919. | 323 | Lacaille 1940 |

| Cuxton. Ficron. 2005. | 307 | Wenban-Smith 2004; 2006 |

| Maritime Academy, Ficron. 2022. | 296 | This article |

| Shrub Hill. Point. 1869. | 285 | Wymer 1985 |

| Canterbury West. Ficron. | 285 | Knowles forthcoming |

| Broom. Type Unknown. | 282 | Hosfield and Green 2013 |

| Stanton Harcourt. Demi-ficron. 1986. | 269 | MacRae 1987 |

| Sonning Town. Ficron. 1932. | 266 | MacRae 1987 |

| Warsash. Sub-cordate/ovate. | 262 | Dale 2022 |

| Warren Hill. Ovate. 1932. | 260 | MacRae 1987 |

'Giant' handaxes present a compelling challenge to Palaeolithic archaeology. They are among the most impressive and arresting objects from our Middle Pleistocene record, they have been considered often in our research and yet consensus on the role their sized played in early human society is far from being reached. Given most Late Acheulean LCTs, are generally accepted as hand-held cutting tools, we need to consider whether very large and heavy LCTs were being used in similar ways to the vast majority of much smaller tools. In the absence of meaningful anatomical evidence for variation in hand size for European late Middle Pleistocene populations, it is impossible to determine whether these tools could have belonged to a population containing individuals who could wield these tools effectively as knives. It has also been suggested that very large tools could have been used in a specialised way, such as being placed in the ground to cut material against, rather than held (Foulds 2017). The size symmetry of these tools has been invoked in discussions of early human symbolic and cultural development, with recent consideration of their form playing a role beyond function as a cutting tool (e.g. Spikins 2012; McNabb and Cole 2015; Foulds 2017)

Large ficrons have attracted more attention in recent years owing to an emerging recognition that they, like other distinctive handaxe types, might be temporally constrained in the Palaeolithic record and relate to particular populations or cultures present in northern Europe in the late Middle Pleistocene (Wenban-Smith 2004; Bridgland and White 2014; 2015; Ashton and Davis 2021; Dale 2022). The Maritime Academy ficrons, once published alongside the site's wider archaeological record, dating and palaeoenvironmental evidence, may help to elucidate when these tools were being made and how they chronologically relate to other types and technologies.

While much of this work is for the future, we'd like to conclude by highlighting the proximity of the Maritime Academy site to two other important Palaeolithic localities. The site lies less than 0.5km, and at similar altitude, from the excavations of Cook and Killick (1924) near to All Saints Church, Frindsbury, which produced a large, and currently undated, lithic assemblage including evidence for Levallois core reductions (Scott pers. obs). While a little further afield, the other Medway site of Cuxton lies just over 5km to the south west of the site. Here a very significant quantity of material including not only the second largest British biface, the ficron mentioned above, but a handaxe assemblage dominated by pointed forms but also including cleavers, offers an important comparative assemblage for the Maritime Academy site (Shaw and White 2003; Wenban-Smith 2004). The Cuxton deposits lie at a lower elevation (c. 15m OD) to those recorded at Maritime Academy and they are currently dated by OSL to MIS 7 (Wenban-Smith et al. 2007; Bates et al. 2014). However, correlating the Cuxton deposits with those at Maritime is difficult owing to the position of Cuxton in the Medway gorge through the chalk, and the fact that Cuxton is a Medway terrace and not a Medway tributary site. Future analysis of the Maritime Academy material will allow detailed comparison with these other Medway sites, and a new dating framework to understand technology and cultural variation in Britain during the late Middle Pleistocene at site, landscape and regional scales.

The authors would like to thank the following for facilitating and advising on the archaeological investigation of the site: Bowmer and Kirkland and their archaeological advisor James Archer (RPS) for commissioning and supporting the work on behalf of the Department for Education, and Scott Moreton of Bowmer and Kirkland for his support on site; Ben Found, Lis Dyson and Simon Mason of the Kent County Council Heritage Team for oversight of the project; Prof. Nick Ashton, Prof. Simon Lewis, Prof. Julian Murton, Dr Beccy Scott and Simon Parfitt for on-site discussions of the archaeology. The project was managed by Jon Sygrave and Jim Stevenson for ASE, illustrations were produced by Lauren Gibson and a draft of the text was edited by Jim Stevenson. Archaeologists Lia Schurtenberger and Elisabet Díaz Pila worked with Letty Ingrey, Matt Pope and Martin Bates on the excavation of MA1-3 and the mechanical excavator was operated by James Shoebridge of BPH. The artefacts were managed in post excavation by Stephen Patton. The artefact was photographed by Emily Johnson and Alastair Threlfall, who also undertook conservation of the large handaxe. The authors would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on the paper and to Judith Winters and Internet Archaeology for their kind support with the publication process.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.