Cite this as: Lillak, A. 2023 Nature Management and Protection of Archaeological Sites in Estonia, Internet Archaeology 62. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.62.12

Heritage sites are part of the modern-day cultural landscape; archaeological sites are mostly situated in the natural environment. In Estonia, several archaeological monuments or their vicinity are or have been protected by the Nature Conservation Act in addition to the Heritage Conservation Act. Both heritage and nature conservation share the objective to conserve, but the legislation and the means to do so are different. In this article, I give an archaeologist's point of view about some of the general possibilities and limitations in cases where archaeology meets nature protection, and also provide a very general overview of the nature and heritage conservation system in Estonia.

In 2020, 19.4 % of Estonian land mass was protected under the Nature Conservation Act (see https://envir.ee/elusloodus-looduskaitse/looduskaitse/looduskaitse-110); land mass protected as archaeological monuments by the Heritage Conservation Act is merely 0.11% (48.8km²) of the territory of Estonia (Kadakas 2022). Considering the scope of protected nature sites, the restrictions from the Nature Conservation Act affects more owners than the restrictions from archaeological monuments.

Nature and Heritage Conservation Acts provide various protection regimes for both nature and heritage. The laws state the principles of protection, but during the listing process it is possible for some relaxation to the protection regimes to be made.

The Nature Conservation Act states many different ways to list protected natural objects: protected areas, limited-conservation areas, protected species, species protection site or an individual protected natural object, and different types of valuable landscapes or objects that can be protected at local government level (§ 4 NCA).

Protected areas are differentiated as well: nature reserves, national parks, nature parks, strict nature reserves, conservation zones, and limited management zones, with the latter three used for zoning the first three (§ 26–31 NCA). Strict nature reserve status prohibits all types of human activity in the area except monitoring, rescue, supervision or administration work (§ 29 NCA). Conservation zones are less strict but economic activities, use of natural resources, driving motor vehicles, camping, bonfires, organising public events as well as erecting new buildings are prohibited. Gathering forest by-products, hunting, fishing, maintaining the existing buildings and other activities that do no harm are allowed (§ 30 NCA). Limited management zones allow economic activities and each site has its own set of protection rules that allow the policy makers to change (both easing and tightening) the standard conditions for these zones stated in the law (§ 31 NCA).

There are also limited-conservation areas set for the protection of local flora, fauna and fungi. In cases where woodland is required for the protected species to survive, logging activities are prohibited (§ 32 NCA). In some cases, many different nature protection regimes can be combined in order to ensure the best protection for the specific site and, as sites are varied, a range of options when choosing a protection regime is important.

In the Heritage Conservation Act, there are two possibilities to protect archaeological heritage: archaeological monuments and protected archaeological sites (clause 3 of § 11 of the HCA). At the moment, there are no protected archaeological sites established, but the main difference between archaeological monuments and sites was the obligation to preserve monuments to the greatest extent possible (§ 3 HCA), with no such obligation for archaeological sites (§ 25 HCA, Kadakas 2020, 247–48). Monuments often have buffer zones (§ 14 HCA) around them and sometimes one monument may have different monument classes (e.g. churchyards are usually historical, archaeological and architectural monuments) with some monuments being both archaeological monuments and historical natural sacred sites (e.g. sacred stones or sites).

In protected archaeological sites, it is compulsory to conduct research prior to any building and other soil works (subsection 3 clause 3 § 25 of the HCA) and the use of metal detectors on the site are banned, unless for research, and few service or economic activities are allowed (clause 2 § 29 of the HCA). The same restrictions also apply to archaeological monuments, but, as stated, for monuments, it is possible to demand preservation of the site or parts of it (§ 3 HCA). Also, anyone wanting to cut trees, establish high-growing vegetation, remove or add soil or prepare the land for forest renewal on an archaeological monument has to have building design documents approved and apply for a permit, allowing the National Heritage Board to specify conditions best suited to the monument (clause 3 § 52 of the HCA). The requirements in the buffer zone around the monuments are slightly less strict, but the projects and building designs still have to be approved by the National Heritage Board (§ 58 HCA).

The choice of protection regimes for archaeological heritage is more limited than for nature sites, but as it is more general and the scope of the protected areas is smaller, most of the site-specific decisions are made during project coordination and permit procedures.

Both Nature and Heritage Conservation Acts offer the holders of the protected site opportunity to apply for support to take care of it (§ 18 NCA, § 35 HCA).

The most general compensation for nature protection sites is reducing the land tax on nature reserves, parks and national parks. There is no land tax on conservation areas (clause 11 subsection 1 of § 4 of the Land Tax Act) and in limited management zones and limited-conservation areas, the land tax is automatically reduced by 50% (clause 2 of § 4 of the Land Tax Act). Additionally, in nature conservation, there is compensation for the potential income lost owing to nature protection restrictions. In the Natura 2000 areas, private forest owners can ask for compensation of 110 € per hectare in conservation zones and 60 € per hectare in nature parks, limited-conservation areas or nature parks that are still in the planning stage (Regulation no. 39 of the Minister of Rural Affairs 2015). For forest areas outside Natura 2000, private owners can ask for compensation of 60 € per hectare, in nature parks and limited-conservation areas even if the protection is still in the planning stage (Regulation no. 10 of the Minister of Environment 2014).

Owners of private forest have an additional 5000 € income-tax exemption (only applicable for the income from selling the timber), and this income can be divided between three consecutive yearly tax declarations (clauses 10 and 11 of § 37 of the Income Tax Act).

The Heritage Conservation Act does not allow any automatic compensations, but since 2019, there has been a compensation scheme for all research determined by the Board (clause 2 § 48 HCA). Archaeological research can be reimbursed partially (50% and a maximum of 1500 €) for most occasions, but watching briefs for individuals can be reimbursed fully (maximum of 1000 €). This reimbursement is granted to everyone willing to provide proper documentation, but it must be applied for. The full reimbursement for individual owners has been actively in use and covered most small-scale archaeological research in 2019, but given skyrocketing inflation – 25.2% in August 2022 the maximum amounts of reimbursements in most cases do not cover even the smaller scale excavations and the situation is exacerbated.

There are funds available for the owners wishing to do maintenance or conservation work on the monument to apply for. For any routine work, there is an application deadline on 30th September each year, but for unforeseen emergency work, funds can be applied for all year around (Regulation no. 22 of the Minister of Culture 2020). For archaeology, not many people apply for the maintenance/conservation funds. In 2022 there were two applications while in 2021 there were five. It is not certain whether this option is not well known among the owners or whether they know the competition is tough – only about half of the routine applications get funding. Nevertheless, there have been several large sums paid for excavation-related emergencies to help the owners cope with unexpected situations e.g. emergency excavations in Narva centre where a heavily disturbed plot of land had to be surveyed in order to understand whether there was any archaeology left, or excavations on an unexpected cemetery in the centre of Viljandi (see Heritage funding)

In summary, for nature protection sites, there is an automatic support system – the land tax reduction. To encourage people to follow restrictions and compensate for the lost income there are other subsidies that do not require any action except to apply for the support. There are action-related subsidies to encourage proper management when it is not the most profitable. For archaeology, it is possible to apply for support for maintenance or conservation of the site and to apply for (partial) reimbursement of archaeological research costs. The measures for archaeology, as well as for other monument types, are solely action-related – the owners will not have any support unless they are either actively conserving or tackling (in most cases partially destroying) the monument.

In some cases, additional nature protection of the archaeological monuments may be even beneficial for the owners as the management of the land is already limited, but many nature protection regimes offer land tax reduction and compensation for protected forestland. Nevertheless, owners coordinating any projects will have to deal with two different boards, permits and acts and the projects 'burden' several state agencies as well (Figure 1). Therefore, double protection is expensive for the state.

Even though the National Heritage Board as the manager of the archaeological heritage in Estonia does not own any land or monuments, the state owns a large number of archaeological sites (Kadakas and Lillak 2020). The sites owned by other state management companies are usually managed without archaeologists being actively involved, but specialists are always required and included for larger projects.

According to Kadakas (2022), 47% of archaeological monuments (excluding settlement sites) in Estonia are located on forest land, 28% on pastures and meadows, and 19% on arable land while just 6% of archaeological monuments are located elsewhere (private gardens, transportation land, wetland etc.). One of the main managers of the land is State Forest Management Centre (SFMC) – a state-owned company managing all state-owned forest, c. 30% of Estonia and 45% of all the forests in the country (see https://rmk.ee/organisatsioon/tegevusvaldkonnad). This makes SFMC one of the main managers of archaeological monuments as well.

There are no archaeologists working in the SFMC, but one of their objectives is to organise the sustainable recreational use of the natural environment in state forests. Their Visitor Management Department has three spheres of activity: creating opportunities for common right of access in RMK's recreation areas and protected areas, planning and creating hiking opportunities and environmental education activities. The SFMC also has been mapping heritage culture sites and the 38,000+ sites already mapped are complementing the information about monuments in the National Heritage Board (see RMK Heritage).

Estonia is covered with SFMC hiking trails and the trails are equipped with information about nearby sites, nature and their importance in the local ecosystem. For historical or archaeological sites, the SFMC has been consulting with archaeologists, students as well as local history enthusiasts, to improve site access as well as provide more information for the visitors, e.g. 'Lights On!' amelioration project for historic sites. As most archaeological sites and monuments are located in nature, it is very easy to incorporate archaeological heritage in nature trails, as it is quite often considered a part of the natural landscape and advertised as such.

For larger sites, the SFMC monitors the number of visits and their visitor survey in 2021 has recorded visitor numbers for several archaeological sites (Table 1). Most of these archaeological sites are associated with other popular tourist attractions and beautiful scenery, therefore it is not known whether these visitors chose the location for its history or natural beauty, but we can assume that the visitors left the site with more knowledge about the archaeological side of the location.

| Site | Number of visits in 2021 (April–November) |

|---|---|

| Rõuge Ööbikuorg – hill fort, Iron Age household reconstruction | 15,500 |

| Lõhavere hill fort | 15,900 |

| Varbola hill fort | 11,100 |

| Neeruti hill fort | 6500 |

| Kaali complex site | 79,900 (throughout the year) |

| Tsitre (port and dwelling site) | 11,400 |

| Tellingumäe (sacred stone) | 10,200 |

| Sinialliku (hill fort and sacred spring) | 4200 |

In this way, the co-management of nature and archaeology is beneficial. The information about archaeology is also displayed on nature trails and even people not intending to visit archaeological sites may find themselves learning more about history.

It is evident, that for some areas, the two different protection regimes complement each other – the Heritage Conservation Act often focuses on the below-ground archaeological resources, and the Nature Conservation Act focuses more on the values above the ground. The Nature Conservation Act regulates quarrying and mining while the Heritage Conservation Act regulates cutting trees on archaeological monuments – some of the constraints are overlapping and, in some cases, may not work well together.

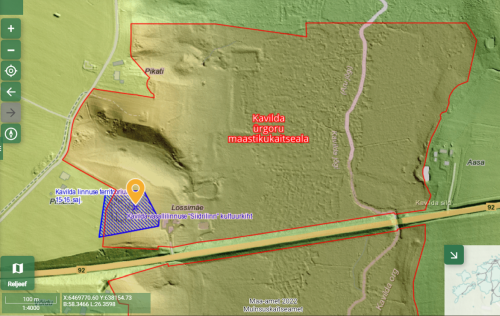

For example, in 2019, nature protection regulations for Kavilda nature protection zone were being renewed (Regulation no. 56 of the Government of the Republic 2020). In this area, there is a fort site with medieval castle ruins (Figure 2, National Registry of Cultural Monuments no. 12915, National Registry of Cultural Monuments no. 7246). The Environmental Board renewing the rules contacted the Heritage Board during the process to discuss the protection rules before their final approval. The rules may have been interpreted in such a way that an archaeological survey as well as any excavations would have been forbidden on the site, therefore they added that archaeological surveys are allowed as long as no harm is done to the protected species, and that archaeology is not comparable to quarrying according to the Earth's Crust Act. This way, archaeological surveys can be allowed and support for the fort's maintenance or conservation can be claimed.

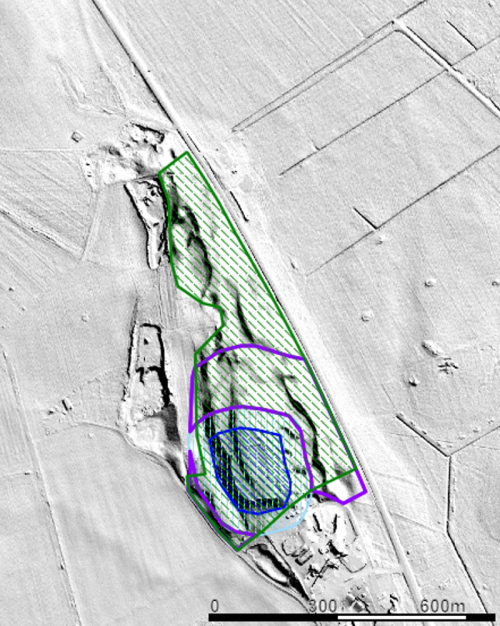

For some places, double protection is essential for preservation. For example – the Kloodi Pahnimägi hill was partially protected as a landscape conservation area since 1958 (Jonuks 2021). Some parts of the hill have been quarried since the 1960s and in 2015 the Ministry of Environment revoked the protection as there was not enough landscape left to protect (Regulation no. 11 of the Government of the Republic 2015). Their reasoning was that the most prominent and best-preserved part of the hill is a hill fort which is also protected as an archaeological monument. Not realising at first that the revoking of natural protection would result in an application for mining rights, the National Heritage Board agreed. The borders of the hill fort in Pahnimägi were not accurately shown on the map and there was believed to be a dwelling site on the northern side of the slope, but no survey was conducted, as this part was believed to remain untouched. In 2017, the local authorities adopted the area as a landscape conservation area of local significance (Regulation no. 8 of Rakvere municipal council 2017), and gave the archaeologists a bit more time to conduct a survey and adjust the boundaries for the hill fort and determine the presence and boundaries of the dwelling site (Figure 3; Jonuks 2021).

The Pahnimägi case has taught the National Heritage Board that in cases where nature protection of a double protected site is revoked, it would be advisable to investigate the surroundings of the monument immediately with more up-to-date methods to check whether the boundaries of the monument need to be larger.

Nature and heritage conservation do have similar goals, to minimise destructive activities on the sites and objects as well as maintain the natural or historic environment. Nature-centred management of archaeological sites is working well, as nature trails encourage people to visit archaeological sites where nature and history education complement each other.

It is certain that different policymakers should enhance their dialogue and the overall protection system of nationally important sites. In most cases, the different protection regimes complement each other, but where double protection of the sites share borders and practically the same protection rules, the site may not need double protection and double management. Nevertheless, revoking double protection is not risk-free in terms of conserving the site. Therefore, any plan to revoke one of the several protection regimes of a site must be thoroughly analysed based on different possible outcomes, as it may trigger the need to reassess the other protection regimes.

I would like to thank Ulla Kadakas and Helena Kaldre for their useful feedback.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.