Cite this as: Schönbeck, M. 2023 Sweden's First Restoration of an Ancient Monument - the burial ground Hemlanden on Birka, Internet Archaeology 62. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.62.4

Ancient remains and their preservation have interested humans for centuries if not millennia. From the Late Iron Age and into the Middle Ages in Sweden, it was not unusual for a stone axe to be hidden in one of the walls of the house or hung from the ceiling to minimise the risk of lightning striking the house. The stone axe symbolised the thunder god Thor's hammer Mjölnir, the one that Thor hurled at the clouds creating thunder.

During the the Era of Great Power (1611-1718), ancient remains were used as a manifestation of Sweden's greatness. In 1630, Johannes Bureus was appointed the first national antiquarian by King Gustav II Adolf. Johannes Bureus travelled around the country and studied rune stones, collected coins and old chronicles, law books, letters and manuscripts. Under the leadership of Bureus, this collected knowledge laid the foundation for 17th century research on ancient monuments, and by extension for today's cultural environment conservation. In 1666, Johan Hadorph, the seventh national antiquarian to be appointed, published Placat och Påbudh, Om Gamble Monumenter och Antiquiteter. It is Sweden's first approach to antiquities law and one of the oldest antiquities ordinance in Europe.

The need for protection was great because many ancient remains were damaged when digging for treasure or when burial mounds were used as brick kilns or earthen cellars, but with the death of Karl XII in 1718 and the end of the Swedish Empire, interest in antiquities and antiquities conservation waned. This period of lack of commitment effectively extended into the 19th century.

Studies of antiquities were considered outdated and were overshadowed by the new interest in natural science in the 19th century which is characterised by mechanisation in agriculture, agricultural reforms, population explosion and burgeoning industrial development, all of which meant major changes in the landscape. As a result, voices were raised during the late 19th century that industrialisation, modern agriculture and forestry were a threat to the natural landscape. In 1867, a new antiquities ordinance came into being, which, among other things, stipulated that interventions on all types of ancient monuments were illegal and carried a penalty.

The researcher and explorer, Professor Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld wrote in 1880 that protected areas should be established where forest and land and lake would be left completely untouched so that the young generation would have the opportunity to see the original Swedish landscape as inhabited and worked by their ancestors. Nature would be left 'undisturbed' (Nordenskiöld 1880, 10).

Even for the conservationists of the time, the ideal was a prehistoric landscape, something wild and abandoned where nature had taken over and it applied both to natural areas and cultural heritage. In nature conservation, the concept of 'free development' or 'non-intervention management' was born, a concept that also came to apply to management (or the total lack of management). It also applied to cultural environments and ancient remains and went so far that in 1874, the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities awarded a medal to a landowner for having 'sanctified' a prehistoric burial ground by planting trees on the graves (Danielsson 2006, 12). The trees would help to emphasise the image of the abandoned and the wild. Areas previously open and claimed by management or grazing for hundreds of years would become wild. The royal mounds in Old Uppsala, which had been left open and cultivated by mowing and grazing, were partially planted again in the 1880s. This view that nature should be left 'undisturbed' appeared in nature conservation as a form of protection until the beginning of the 21st century, and then transitioned to a simple and, above all, cheap form of management.

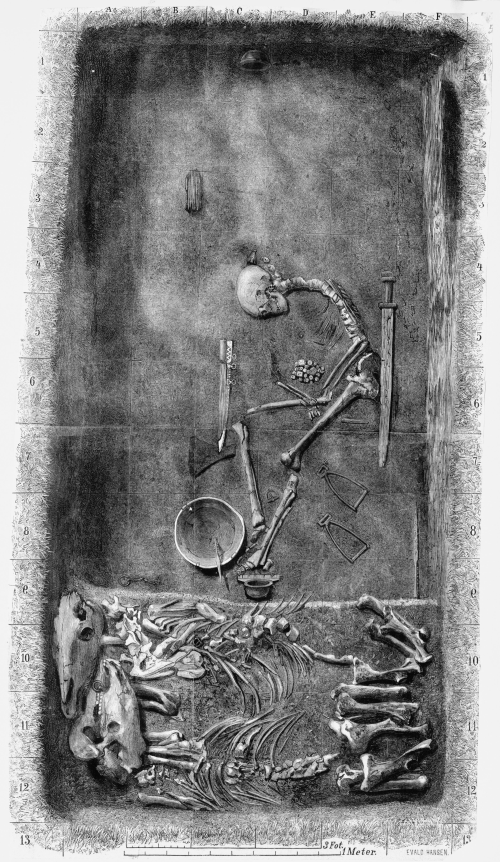

During the second half of the 19th century, knowledge about our prehistory emerged and archaeological methods began to be developed. A large part of this development can be attributed to Hjalmar Stolpe (1841-1905). He was a zoologist, botanist and geologist. In the course of his work on the geological history of amber, based on insects enclosed in it, he went out to an island in Lake Mälaren, which was said to be rich in this material (Arbman 1941, 146).

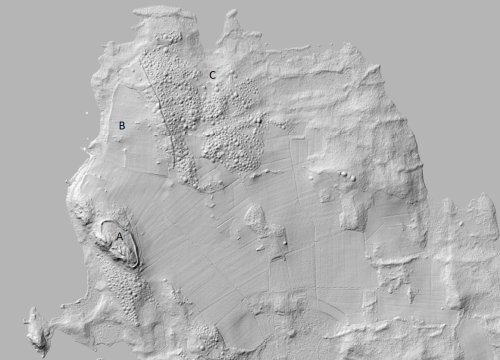

The island in Mälaren that Hjalmar Stolpe came to visit was Björkö (Figure 1). Since the 17th century, historians have considered that the place mentioned as Birka in Rimbert's Vita Anskarii is located on Björkö (see Odelman 1986). The director of what would later become the Swedish National Archives, Johannes Messenius, wrote in 1612 that 'every youngster in Sweden knows that Birka was on Björkö' (Ambrosiani 2013, 8). The first excavations, in which National Antiquarian Johan Hadorph participated, were carried out as early as 1680.

The oldest written documents that mention Birka are Rimbert's Vita Ansgarii (Life of Ansgar) which describes the life and work of the missionary Ansgar and his missionary work at Birka around the year 830, which was recorded in 865-876 by Rimbert, Ansgar's successor as Archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen (see Odelman 1986). This document is contemporary with Birka. Birka is then mentioned in writing in Adam of Bremen's Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Ponteficum (Episcopal acts from Hamburg Church) (see Svenberg 1984) and in it, Archbishop Unni's life and his death in Birka in 936 are described.

Birka was founded around 750 AD, and it flourished for more than 200 years (Figure 2) then abandoned in about 975 AD. It has been estimated that the population of Viking Age Birka was between 500 and 1000 people.

The area that Hjalmar Stolpe came to investigate when he came to Björkö in 1871 was the area known as 'The Black Earth'. The area was a cultivated field at the time and Stolpe wrote that even after the removal of the first sods, he could ascertain that these cultural layers were the remains of a settlement and trading place, and he did not want to leave Birka/Björkö until he investigated the area further. Hjalmar Stolpe came to conduct the first scientific archaeological investigations at Birka and continued until 1881. Between 1881 and 1895, investigations were carried out sporadically. His work came to develop the archaeological documentation methods, which in principle are still in use today.

Stolpe came to investigate a total of about 5000m² of the Black Earth and a total of about 1250 of the 3000+ registered grave remains (Figure. 3). The archaeological results attracted a lot of attention and resulted in exceptional finds. The number of visitors to Björkö increased, not least when several of Stockholm's shipping companies organised 'pleasure trips' by steamboat to the island. In 1888, Hjalmar Stolpe published a guide for visitors with a description of the ancient remains, the finds and the history of the place (Stolpe 1888). Parallel to the archaeological investigations, the farmers who owned the land on the island carried on with agriculture and animal husbandry as usual.

During the 18th century, thoughts and ideas about various land reforms began to spread in Sweden. Inspiration was drawn from England, Germany, and Denmark, where similar reforms had already been implemented with successful results. The basic idea of the land reforms was to make farming more efficient by limiting the number of fields and meadows per farm and instead grouping the individual farm units' properties into larger undivided parcels. The land reforms, 'Laga skifte', were of great importance for the future development of agriculture and resulted in increased cultivation and grain production.

Before the plans to carry out this land reform, the farmers on Björkö began to cut down the small amount of forest that was on the island. On a map from 1747, it appears that the small forest that grew on the island was barely enough for fencing material. The map descriptions state that there is fine birch forest on the island. According to a travelogue from 1811, however, there was no birch on Björkö (literally the birch island) (Figure. 4). There were also plans to sell off land within the Black Earth and on the large adjacent burial ground Hemlanden in order to construct holiday homes. This led to the question of whether Björkö should be bought by the state in order to preserve the ancient remains. There were plans for the state to buy the whole of Björkö, but as several landowners did not want to sell, only the northern part of the island came up for sale. After a parliamentary decision in 1912, the state bought the northern part of Björkö, the area where most of the ancient monuments are concentrated (Gustawsson 1977, 87).

The area that the state bought covered about 150 hectares, of which about 50 hectares were cultivated arable land while the rest was meadow and pasture. After the purchase, all grazing and mowing was prohibited on the Hemlanden burial ground and overgrowth took off. Previously this land had been open and grazed and only a small number of trees grew there, as can be seen on the older maps.

This was the first time the state had purchased an area of ancient remains where previously only nature conservation areas had been purchased. The reason why all traditional management was prohibited on the purchased land was due to Sweden's first nature conservation law from 1909. As a result of this law, the first national parks in Sweden were also established on state-owned land at that time. These areas were then left for 'free development' or 'non-intervention management'. The idea was that the land areas should be left undisturbed and exhibit nature untouched by humans. The same thoughts came to apply to Birka. Not a tree was to be cut down, not a branch was to be broken. Wild vegetation was thought to be characteristic of the ancient landscape. The first decision after the state bought the area was to prohibit the area from being grazed. Land that had been pasture for hundreds of years was left for overgrowth (Gustawsson 1977, 91). The overgrowth happened quickly (Figures 5 and 6), and the ancient monuments were damaged by this. The antiquarian authorities complained, but no one listened.

In 1931, the grounds were so overgrown that it was barely possible to get through the area. Trees had damaged several graves and something had to be done. So, based on the historic maps, the former meadows and pastures began to be re-created.

The purpose was to restore the old landscape, to reclaim the meadow and pasture and to restore the ancient monuments to their prominent place in the landscape and to re-create the former vegetation. Trees were removed from the hillfort. In the Hemlanden burial ground, the spruce was removed but the birches were spared. These had re-established themselves after being felled by farmers in the 1890s. Wild apples, pears and cherries were saved (left over from gardens in the area), and grazing animals (sheep) were reintroduced.

The measures received a lot of criticism and limited funding. The work had to be stopped several times owing to lack of understanding. The restoration work did not receive any support from either the nature conservation movement or from antiquities associations. In newspapers, there were articles and submissions about the damage caused to this strange landscape. Critics argued that the area was being restored to death. They wanted to stop the restoration work, and partially succeeded. From 1934 until 1938, restoration work was completely stopped in an area south-east of the hillfort, but could continue in other areas, including at the Hemlanden burial ground (Gustawsson 1977, 98).

In 1938, a reputable antiquities association visited Björkö. The aim was to extend and expand the ban. Instead, however, they were impressed by the other restoration of the landscape - not least the work at the Hemlanden burial ground (Figures 7-9). During the 1940s and 1950s, representatives from, among others, the Swedish Nature Conservation Association and the Forestry Agency visited Björkö to study the restoration work (Gustawsson 1977, 99).

It turned out that the restoration was very labour-intensive and therefore costly. Single monuments such as a burial mound could require several hundred person-hours, and archaeological sites such as Björkö turned out to require thousands of person-days to restore (Pettersson 2001, 203).

There were no state funds for the restoration work. The money had to be taken from other grants, funds and individual contributions. During the first part of the 1930s, however, a highly significant contribution was added with the establishment of the Gustav Adolfs fund for the care of Swedish cultural monuments. It had been founded in connection with the Swedish National Heritage Board's 300-year anniversary in 1930. From 1932, the fund was able to offer around 25,000 kronor (which corresponds to approx. €82,000 in today's monetary value) in annual disposable returns for the preservation of ancient monuments (Pettersson 2001, 203).

The importance of the fund money took on extra value in the time of the Great Depression and the recession during the 1930s. Paradoxically, the preservation of ancient monuments still benefited from the economic situation because state and municipal labour market support for the unemployed was introduced, which could be used for cultural environment conservation.

After several years of working against the wind, the criticism turned to cheers and applause. It took just over 10 years of restoration work to return the pastures and meadows to their former appearance. Only then could the annual maintenance work of clearing and grazing be introduced - work that is still carried out at Birka today. That the work has been successful speaks volumes for the large number of visitors who come to the island annually. In 1950, Björkö was visited by about 20,000 people, in 1973 by 50,000, and before the pandemic in 2019, about 80,000 visitors came to the island.

Another sign that the place is unique is that Birka and the adjacent Hovgården on Adelsö were designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993. Sweden has 15 different World Heritage Sites, Birka being one of them. On UNESCO's website it says that '…Birka and Hovgården represent complete and exceptionally well-preserved archaeological sites from the Viking Age. In this serial property, the surviving visible evidence of the prehistoric society includes structures in the mercantile town, the royal domain and the harbor, defense systems, and prehistoric cemeteries'.

The Swedish National Heritage Board has let the experiences of the work at Björkö become a guide for the continued work in Sweden to make cultural heritage visible and care for it. For several years, the work was carried out as a labour market project across the country. In 1996, responsibility for the work was transferred to the country's 21 County Administrative Boards. There are currently more than 2000 archaeological sites in Sweden that are managed in a similar way to Birka. However, this management, whether carried out through mowing, clearing or with grazing animals, is not only beneficial for the cultural heritage but also beneficial for the biological cultural heritage. Nature talks about culture. Biological cultural heritage is a concept that focuses on the understanding of the connections between nature and humankind's use of nature. These connections can be used for historical and biological knowledge and application in nature and cultural environment conservation.

Many of these areas are also located on privately-owned land - by individual, municipal or land owned by the church. Through long-term agreements between the state and landowners, the management is carried out either by the landowner in person, by tenants or through contractors or local associations. Most of the costs for maintenance and information efforts are paid for through annual government cultural environment conservation grants or through the European Union's common agricultural policy. The experiment, which was started almost 100 years ago by the Swedish National Heritage Board because nature conservation had a target image of what 'real nature' should look like, has not only saved several of the country's unique ancient monuments, but also benefited biological diversity. Care and maintenance of our cultural heritage plays a more important role for nature than might be expected.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.