Cite this as: Kersting, T. 2024 Archaeological Heritage Management and Science on War and Terror Sites in Brandenburg, Germany, Internet Archaeology 66. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.66.14

Beneath the visible landscape lie numerous layers, invisible at first sight: this is familiar territory for archaeologists. That more or less the entire landscape is 'contaminated' with the history of terror, with its abuse for purposes of the exclusion, exploitation, and acceptance of the complete annihilation of people is a thought that imposes itself when trying to trace the sites of terror in the landscape (Bernbeck 2017, 7, after Pollack 2014, 53, who also takes a decidedly archaeological perspective). The variety of archaeological monuments from 20th-century wars preserved in the soil of the federal state of Brandenburg is wide, and includes examples from the military-weapon industry, traces of the war itself (crashed aeroplanes, trenches), relics of terror (mainly camps and industrial grounds), and of suppression by National Socialist-dictatorship in East Germany. Many of them have already been investigated by researchers with the State Archaeology Museum in Brandenburg over the last 25 years (Haubold-Stolle et al. 2020, 187-221; Kersting 2022; for examples from Berlin, which is a separate federal state with its own heritage management, see Haubold-Stolle et al. 2020, 170-86).

Most modern monument protection laws in Germany no longer have any age restriction for archaeological monuments. In many regions there is a considerable density of sites and material witnesses of war and terror from two world wars. Archaeology of contemporary history is not an academic gimmick for archaeological heritage management, but a concrete and urgent duty: the monuments are there and their number is decreasing. Since the mid-1990s, the monument offices have been dealing with a broadening range of 20th-century monuments in the ground. The 'omnipresence of concentration camps' is a fact and a task for archaeology. And yet they are only part of the variety of monuments from the war-torn 20th century that are preserved in the ground. Cellars in bombed inner cities such as Dresden and Berlin have also been excavated (Figure 1), landscape-defining relics of fortifications and battlefields such as the Westwall (Figure 2), Hürtgenwald and Seelower Höhen are protected and researched as archaeological monuments - as are groups of bomb craters preserved in the forest (Figure 3). Sometimes even graves of fallen soldiers can become the subject of archaeological documentation during planned reburials, although they are normally protected as war sites (Figure 4).

The reaction of the public is often quite different from their reaction to 'normal' archaeology: aspects of crime and suffering, victims and commemoration have to be taken into account. Here, archaeology takes on a new role: it gains current social relevance as a body of evidence against tendencies of relativisation and denial of Nazi crimes.

As early as 1990/91, the first regular excavation took place in a forced labour camp in Germany at Witten-Annen an der Ruhr - it remained without a successor for a long time. Today, quite a few camp sites from the Nazi era have been at least partially archaeologically investigated, especially at sites of concentration camp memorials and large forced labour camps. In addition, the topic has a European connection owing to the expansionist drive of the National Socialists: today, camp sites are being investigated in many formerly occupied countries.

Archaeology can make a decisive contribution to the construction history of the camps - the inmates, who were segregated according to political and racist criteria, spent a large part of their daily lives in these places. The structural condition, equipment and organisation directly influenced their chances of survival, which is why the construction findings of the camps, their spatial distribution and functional differentiation are indispensable sources. The problem often surfaces because of subsequent use in eastern Germany by the Soviet military which demolished or built over the camps. In some places, the continued use of the camps as Soviet 'special camps' creates new perpetrator-victim constellations, which with their 'double history' and the implied 'victim competition', also raise their own commemoration problems. However, their very character as 'places of suffering' also facilitates their protection: today, the designation of camp sites as archaeological monuments is often welcomed. Nevertheless, research on camps via local initiatives often does not reach the state offices because, with the well-meaning intention of creating places of remembrance, there is a lack of awareness that these sites are also archaeological monuments.

Redesigns, road construction and pipe laying led to the first investigations in concentration camp memorials. The remains of entire subcamps fell victim to the construction of new industrial estates. Excavations during youth camps at concentration camp memorials also add to the picture. In the future, the associated factory areas themselves, which were no less places of suffering and exploitation, will also become the subject of archaeological research. Only recently, a complete concentration camp subcamp was found in the cellar under the remains of the so-called 'Deutschlandhalle' of Daimler-Benz (Figure 5).

A comprehensive inventory is the task of monument preservation, which also includes the systematic evaluation of historical standard works and sources, historical aerial photographs and digital terrain models. For state archaeology, besides the suffering of the victims and the guilt of the perpetrators, the exact position of the crime sites is of paramount interest because only in this way can they be protected.

(How) can original structures be preserved? Again, primary conservation means preservation in situ, e.g. visible (which raises questions of conservation and presentation) or invisible, with permanent preservation of the structures hidden just below the surface. Secondary conservation, on the other hand, means 'preservation' in the form of documentation and finds on the shelf and in digital storage, with abandonment of the original substance. As always, a decision is arrived at in the process of weighing up public concerns, although commemorative and remembrance aspects also play a role here.

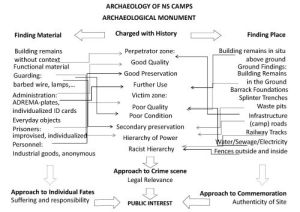

Perpetrator sites are more problematic as monuments and it is more difficult to communicate reasons for their preservation. Public acceptance is low in contrast with victim sites. However, the perpetrator sites are often better preserved because of their higher quality construction, and because they can still be in use, while the victim sites of simpler design are decaying and often cannot be saved. The archaeological monuments are linked to people and their fates and charged with history(s), which has an effect on the character of finds and features. In fact, finds can be evidence and features can be crime scenes (Figure 6).

This means that the public's interest often moves (too) early in the direction of the 'memorial site', as the supposed authenticity provides the credibility. The finds themselves are atmospheric and emotionalising to an otherwise unknown extent in archaeology, and are often personalised, assigned to individuals and their fate, and 'compensation relevance' may also be a factor. For example, found factory identity cards or data carriers (e.g. Adrema plates) of the administrations serves as evidence of the labour employment in Germany. Unfortunately this avenue of proof will be lost in the future with the passing of the victim generation.

The analysis of 20th-century find material is often difficult, but only an exact dating leads to the interpretation of a find as a Nazi camp (Figure 7). Materials of a new type accumulate, with a dating framework that is unusually narrow for archaeological objects. The problem of preserving and storing 'modern' find masses is growing, given the limited capacities of the state offices, but must not be solved by rigorous selection during the excavation.

Dealing with sites of terror as archaeological monuments first had to develop. At the beginning of the 1990s, excavations were carried out as 'maintenance measures' by local initiatives with the best of intentions (Figure 8). At the same time, an 'ideological change of remembrance' began in the large concentration camp memorials in East Germany, and which led to redesigns and remodelling (Figure 9). In this phase, there was strong support for the state archaeologists to take responsibility - no memorial wanted or wants to be an archaeological monument. People feared delays and costs.

As smaller camp sites were excavated, those involved gained further competence. The public perception of such excavations away from the large memorial sites, in their own local environment, caused a rethink in the early 2000s, especially when the excavations were accompanied by an exhibition. Well-intentioned activities by interested amateurs began to be professionally accompanied, such as at a forced labour camp near Treuenbrietzen, where schoolchildren found tin Adrema matrices from the factory administration with names, addresses, birth and other data on them about forced labourers (Figure 10). The personal data have been taken over by the Arolsen Archives and they are no longer just about the archaeology (see the whole story in this film).

Suitable anniversaries sometimes also helped to convey the contribution of archaeology to the public. A research excavation by the FU Berlin began in 2015 just in time for the 100th anniversary of the start of construction of the first mosque in Germany at the WWI 'Half Moon Camp' for Muslims in Wünsdorf (Figure 11). This was where the 'Jihad in the name of the Kaiser' was supposed to have started and where detainees of the Islamic faith were incited to wage jihad against their 'colonial masters'. At the time, Berlin ethnologists were also using the prisoners for linguistic, musical and racial research. Because a reception camp for modern day asylum seekers was being built on the same site, the public interest was very high, especially in the Muslim community.

Another example can be seen in the Red Army forest camps in Brandenburg which were presented in a travelling exhibition in time for the 70th anniversary of the end of the war (Figure 12). Forced labourers from western Germany were also interned there as displaced persons or 'repatriates', identified by the characteristic materials that were found. For the 50th anniversary of the construction of the Berlin Wall in 2011, excavations were carried out in the former border fortifications and uncovered an escape tunnel. Here, too, the public's attention was great, as might be expected (Figure 13).

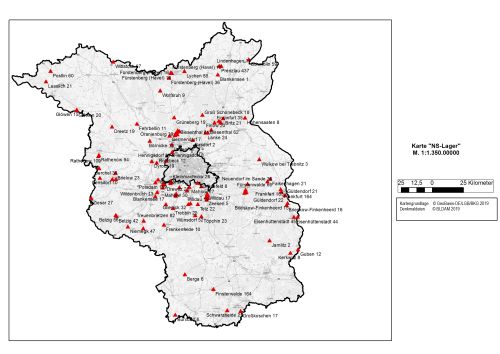

The 20th century is considered the 'century of camps' (Kotek and Rigoulot 2001). This article is intended to make available the archaeological knowledge about camp sites of the WWII era in the state of Brandenburg, knowledge that has been stored in the archives and magazines of the State Archeology Museum. It does not replace a scientific reappraisal of the relevant features and finds, nor is it a comprehensive comparison with historical sources. My goal is to make accessible the information about this ubiquitous type of monument that has been generated by numerous archaeological investigations since the 1990s in Brandenburg State (and greater Berlin, too) to all those who might be interested. The findings I discuss are also the subject of the exhibition Exclusion - Archaeology of NS-Forced Camps, produced by the Brandenburg State Archaeology Museum and the Nazi-Forced-Labour Documentation Center in Berlin Schöneweide, which opened in May 2020.

Though 'NS forced labour camps' encompass quite different categories within Brandenburg, the material remnants will be viewed as a whole from an archaeological perspective, always bearing in mind the historical and theoretical attention that has been devoted to this topic (Kotek and Rigoulot 2001; Greiner and Kramer 2013). It is always about areas with temporary limits, which define an inside and an outside, where groups of people were included and excluded at the same time. The Nazi camps can be described as a 'no-go-landscape', to which only perpetrators and victims had access - and the latter usually had no possibility of escape. Thus is a 'terror landscape' defined (Kersting 2015, 57).

The focus here is on the domestic development of confinement infrastructure during the Nazi period in the form of early concentration camps, the later, large concentration camps and their satellite camps, WWII POW camps, forced labour camps, so-called labour education camps, and other Nazi-period categories. As archaeologists, on the one hand we should avoid the obfuscating terminology of the time, but on the other hand because each camp typically had multiple functions, held different groups of people, and was characterised by varying conditions, either sequentially or simultaneously, we cannot help but make use of it at times.

'Camp Archaeology' serves both the legal and social mandate of monument protection and scientific interest. The present study considers the aim of camp archaeology to be the recording of the camp sites in Brandenburg in a systematic fashion. To that end, a wide range of sources are available, consisting of very different institutions and social groups with interests that vary considerably. For the Brandenburg State Archaeological Museum, the exact locations of the sites are of supreme importance because these data provide the basis for the listing and protection of the material resources as archaeological monuments. In order to unearth information that is often hidden, all sources have to be evaluated carefully and compared with each other, as the exact locations of the crime scenes (for that is what they are) is often only of secondary importance in written sources and historical investigations. In these, of course, the suffering of the victims and the crimes of the perpetrators are more important.

In the standard works on the concentration camps in the state of Brandenburg (Benz and Distel 2005-2009, mainly volumes 3 and 4 on the Sachsenhausen, Ravensbrück and Buchenwald camp systems) location information is mentioned only rarely, and in those few cases without much precision (as is the case with documents in the large databases of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). Sometimes historians write things such as 'nothing remains of the history' or 'nothing is left there', but they do not bear in mind the fact that the archaeologist's work typically begins under those circumstances (Schute 2018, 595). The compilations of the Federal Agency for Civic Education on the memorials of Nazi crimes (Endlich et al. 1999) and the Brandenburg State Agency for Civic Education (Scheer 2003) sometimes provide references to locations. The historical reappraisals and directories of historical sources (files, etc.) of the Berlin and Brandenburg state archives (Bräutigam 2003; Kubatzki 2001; Meyer and Neitmann 2001) and of the memorial sites (Morsch and Ohm 2014) sometimes give postal addresses of places where forced labourers were held, but these often concern accommodation in existing buildings which is not a topic for archaeology. A search of historical aerial photographs and the creation of digital terrain models are necessary to guide fieldwork. Allied images from the 1940s and the Soviet aerial survey of 1953 are available from the Landesvermessung und Geobasisinformation Brandenburg (LGB) in Potsdam, but they are of course not comprehensive and are not thematically indexed in any way.

For places in the immediate vicinity of Berlin, the timeline function on Google Earth can also be used as a source. The 1953 images of Berlin are integrated there, which usually show a belt of some hundred metres outside the city limits where the remains of many camps were located. The 1:10,000 topographic maps from the era of the German Democratic Republic, which are also available in digital form, often offer valuable information about remaining and converted camp buildings and paths, fire water ponds, etc., most of which no longer exist above ground.

Information from local initiatives supplements the visual evidence because often the knowledge of the existence of such places has been passed down through the generations (Pollack 2014, 71). Local histories, self-published in very limited runs and low coverage, are often very informative because the authors typically go into great detail. The published research is supplemented by websites of amateur researchers. These sometimes provide quite valuable location information (this is also where the grey or perhaps better 'brown' zone of 'dark tourism' begins, where places of the Nazi era are brought to the attention of an interested public (Bernbeck 2017, 415), as do people involved in the geocaching scene who sometimes discover sites that scholars have not yet. Another resource consists of the youth projects of the Landesjugendring Brandenburg (Brandenburg State Youth Council). These projects, funded by the council through various mechanisms, enable schoolchildren to explore the local past, visit local camp sites, and interview contemporary witnesses, gathering photographs and recording oral history. The Brandenburg State Archaeology Museum has recognised the potential here and invites the youth groups to the museum, where researchers explain how contemporary archaeology works and give the young people the opportunity to 'grasp' history with the help of actual artefacts. In return, the young people share their local knowledge. Finally, volunteers and metal detectorists who are interested in the topic send find reports of camp sites to researchers at the museum that can be verified professionally and eventually protected legally.

All of the scholarly activity has the aim of registering camp sites as archaeological monuments in the Brandenburg State Monument List in order to ensure their permanent preservation. However, an equally important goal must be communicating information, whether at the original site, in the museum, or in appropriate formats at the memorial sites. It is along these lines that scholars investigating the remnants of German internment camps on the British Channel Islands, for example, recommend taking a 'non-invasive approach' (Sturdy-Colls and Colls 2013, 128; Carr and Jasinski 2014; Carr et al. 2018).

By definition, archaeology deals with the material record, and we archaeologists thus do not need to make a 'material turn' to research history (Bernbeck 2017, 222) - it is 'normality' (Schute 2018). For those of us who are archaeologists of war and terror, learning about the fates of our research subjects can be emotionally burdensome but it is also a great opportunity in terms of public perception (Kersting 2020; Meller and Bunnefeld 2020, 103). From a purely legal point of view, archaeological heritage management is conducted in the public interest, but the interest of the public in the archaeology that is closest to our own time is quite different from their interest in that of prehistory.

The material remains are always directly linked to certain people and their fates. This is true not only for the Nazi-era, but here the historical context is more or less known (on the many interrelated questions connected with this issue, see Bernbeck 2017, 92). The structures of archaeological monuments are 'charged' with fate and history (Hirte 1999, 77). This has an effect on both the characterisation of the material finds and the structures of the features of archaeological monument under study; it can be the case that finds are evidence and features are crime scenes (Wagner 2016, 170) (Figure 15).

In contrast to conventional monuments, and as noted above, this means that the public's interest often moves early (too early) in the direction of 'creating a memorial site' as the supposed authenticity provides the credibility, as Ivar Schute also (2018) describes for the Netherlands.

Archaeological heritage management is concerned with material legacies that are present in the terrain 'covered by soil or water', according to the Brandenburg Monument Protection Act (DSchG 2004 §2), and that have a historical and scientific value, thus being worthy of protection. For the Brandenburg State Archaeology Museum, the objects associated with the war and Nazi period are easy to handle because they can be protected, researched, and excavated without public opposition, and because there is a genuine public interest in them. The original sites and their material legacies are indispensable today for the political education of future generations, precisely because of the violent crimes and suffering associated with them. The desire for vivid visualisation has led to the rediscovery of a multitude of previously unnoticed sites. Local citizen initiatives, some of which were mentioned above, have made a significant contribution to the search for traces. The material and social functions and effects of archaeology consist precisely of making visible again what has been hidden. Camp sites and their history thus become anchored in the public consciousness. The visual and demonstrative value i.e. the 'comprehensibility' of the remains of the original camps is especially evident when young people are being introduced to the topic. So it is a matter of real social concern to which archaeology can (finally!) contribute something positive: the enhancement of political education.

What is involved? The vast majority of reports on camps, standard works as well as literature, eyewitness accounts, and memoirs, almost never deal with the material inventory of buildings, facilities, structural design, furnishings, everyday objects, and so forth. Usually the specific location of the 'site of the camp' is not even mentioned. Of course, the focus is always on people and their fates, but archaeology has another approach: the investigation of material remains, which will become more important in the future as eyewitnesses pass away. In terms of the archaeological traces of camp sites that could be recognised as monuments, those of the so-called 'hall camps' do not meet the criteria. The types of buildings that were used for hall camps ranged from schools, gymnasiums, inns, and cinemas to stables on farms (Bräutigam 2003, 35). Hall camps, common in the early Nazi era (and continued to be used to some extent), so are not considered potential monuments because the buildings are still standing. Only after parts of a camp site are no longer above ground or are submerged in water can they become objects of archaeological monument preservation according to the definition in the monuments law. So, while a sunken Spree or Havel barge on a river in which forced labourers were held, as was the case in Spreenhagen (Weigelt 2006, 272), could be declared an archaeological monument, on the other hand, the site of the destruction of the Lost Transport of Tröbitz, which killed prisoners on a concentration camp train (Arlt 2011), is not since the material traces of what happened are missing (though they may yet be found). For this reason, we are talking about camp infrastructure usually erected on open spaces or in the forest that were later partly or completely removed, dismantled, destroyed, or built over - often because the materials could be used elsewhere.

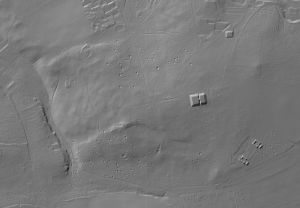

As is the case with archaeological monuments from other periods, the remnants of former forced labour camps can be located in places where nothing at all has been found so far, other than convincing indications of the existence of the original site (e.g. historic town centres that are centuries old). A site having been built over, on the other hand, is by no means proof of the absence of original remains below ground, as many years of experience have shown. Digital surface models provide a deeper level of evidence, i.e. traces in the relief of the terrain from features such as barracks and fire water ponds. Whether these were observed in the terrain itself or only in the model is irrelevant in terms of their monument character. Even if remains are recognisable in the field, it is frequently the case that they have not been archaeologically documented in any way. Building floors, pathways, foundations, cellars, and portions of the sanitary facilities are often still partially visible above ground. Other barracks sites are recognisable through terracing, terrain cuts, or even a treeless place in wooded areas. The range extends from standing buildings to structures of which there are no traces either on the ground surface or below ground.

When is excavation needed? In Brandenburg State, many excavations are the result of so-called linear measures (e.g. road construction, power/gas/waterlines). These too were the reason for the first excavations at Stalag Luckenwalde and Camp Uckermark. Large-scale pipeline relocations necessitated the investigations in Hohensaaten, Brieskow-Finkenheerd, and Groß Schönebeck, and the construction of small pipelines and roads impacted the sites of the camps of Bergolz-Rehbrücke and Jamlitz. Similar situations occur again and again at memorial sites. The destruction of sites as a result of development is not uncommon: the remnants of the Rathenow satellite camp and other areas of Stalag Luckenwalde fell victim to the construction of large-scale industrial facilities. The area of Stalag Fürstenberg/Oder near Eisenhüttenstadt was cleared for commercial development that has not yet taken place. The Siemens camp Dreilinden in Kleinmachnow was destroyed prior to the construction of a residential development and a similar project affected the sparse remnants of a Heinkelwerke camp in Sachsenhausen.

Many of the archaeological monitoring projects at camp sites have been concerned with the renovation or redesign of elements of memorial sites, such as paths, open spaces, and barracks areas. Only a few projects had investigation of specific features as their primary aim. It may be surprising, but there have been no research excavations at NS-camp sites in Brandenburg to date other than those at the Tempelhof Airfield in Berlin by R. Bernbeck (Haubold-Stolle et al. 2020, 117-80). However, experts have led excavations as part of youth camps, such as in Stalag Mühlberg, Ravensbrück, and Treuenbrietzen. And non-invasive research, i.e. without excavation, as at Mahlow forced labourer hospital, can also bring a forgotten camp site back into consciousness.

By 2021, 85 archaeological excavations have been conducted at camp sites in Brandenburg, almost always during or prior to construction. Of these, 27 have taken place in Oranienburg alone at the various Sachsenhausen concentration camp sites, and 15 in Fürstenbergat at the various Ravensbrück concentration camp sites making up around 50% in total between them. If one adds the large prisoner-of-war camps Frankenfelde, Eisenhüttenstadt, and Mühlberg, then two-thirds of the excavations have taken place at the 'large camps', some of which are also memorials. Archaeological investigation of the sites of memorial centres, which Schute (2018, 594) notes as having been part of his practice in the Netherlands and Poland, has also been a significant component of the work done in Brandenburg State. Investigations of around 15 other forced labour camps, some of which are quite large, account for the remaining third. A large proportion of these sites are the so-called 'forgotten camp sites' (Schute 2018, 595). Since the mid-1990s, when camp site excavations began, their annual number rose to a peak in the early 2000s with over 10 per year and then stablised. Since that time the number of excavations per year has varied between two to five. In 2020, excavations were carried out for the first time at industrial sites where forced labourers worked.

Owing to the limited nature of the documentation generated by archaeological mitigation of construction work, the opportunities for insight are often narrow and few. However, this does not mean that no results were recorded. Quite a few documented investigations at known camp sites with confirmed locations did not report any archaeological finds or features. In the Heinkellager Sachsenhausen 37, for example, only a few features were documented (two concrete foundations, brick bases, and a wall corner), all of which were subsequently destroyed by the construction work. When the State Archaeological Museum consequently cancelled the registering of the archaeological monument, the property owner removed the commemorative sign as if the historical site no longer existed or had never been there.

Many of the camp sites that have been located have not yielded any finds as yet, either because no archaeological mitigation has taken place to date or because only walkover surveys have been conducted. It may be that the sites have been completely built over and are no longer accessible on the surface. However, traces and remnants may still be present below ground, so it is possible these sites will be registered as archaeological monuments at some point.

The focus here is on the monuments that have been preserved in the field and are visible to some extent, that can be recognised in the digital surface model, or that have been documented during specific archaeological investigations in Brandenburg State. Broadly speaking, features consist of those camp components that can be seen in contemporary photographs, both aerial and other types. Even if their preservation in the ground cannot be assessed today, there is at least evidence that they existed. These are distinguished from those that are only depicted on plans and so may not actually have been built. A methodologically important observation we made in Ravensbrück in the 1990s applies here in general: A chronological classification of the findings could not always be made clearly, since the changes to the building fabric towards the end of the war and through the subsequent use of the site after 1945 were very close together in time, while in addition, some of the camp-era infrastructure and building fabric has been used, maintained and changed right up to the present day.

Complete ground plans of camps are usually not excavated archaeologically, but the aerial photographs taken by the Allies, which are frequently available in the archives in Brandenburg, offer a large number of examples, both up to and after the end of WWII. The forced labour camps were evidently always tailored to the available plots of land and planned accordingly, and could therefore be roughly triangular (Eberswalde), semicircular (Niemegk), form regular roundels (Dabendorf), or be radially arranged around a central watchtower (Sachsenhausen). Examination of the layouts of the camps suggest that the overriding concern was less design (as perhaps in Sachsenhausen) and more the minimising of expenditures, e.g. for the water/sewage pipe network and security infrastructure.

The remnants and traces of buildings and other camp facilities can be categorised as follows:

Concentration camp prisoners had everything taken from them with the exception of combs, soap, and toothbrushes. It was essential for survival to possess a bowl, a cup, and a spoon because otherwise it was impossible to be given the camp soup. Elie Wiesel recounts the trauma he experiences when he 'inherits' a spoon and knife from his father at the moment when the two are separated (Bernbeck 2017, 200). Prisoners of war possessed little more than their uniforms and boots and what they carried in knapsacks and the pockets of their trousers. The forced labourers who were deported to Germany and put into camps had at best a suitcase or a small bundle of clothes with them. In Eastern Europe, many people were picked up in street raids in their hometowns and were not given the time to pack even the bare necessities for the journey to Germany.

During excavations numerous artefacts were recovered from the sites of the former camps (see Figure 7). The spectrum ranges from barrack building materials related to electrical and water-supply and incarceration infrastructure (insulators, barbed wire), to objects of daily use (soup bowls and spoons, drinking cups, and military eating utensils) to the belongings of the camp inmates (combs, toothbrushes, tokens, writing utensils, and name tags). Many things dating from when the camps were in use have decomposed: finds of paper and other organic material, for example, are very rare. The finds reference the life of the 'excluded' (Bernbeck 2017, 21, 98), the structure, administration, and after-use of the camps, and the actions of the guards, as well the involvement of German society in the exploitation and terror system of the camps. They serve as reminders of the camp sites, which can be characterised as concrete crime scenes, but above all, the serve as reminders of the people who were enclosed here by camp fences, forcibly excluded from the German national community but who remained available for exploitation through forced labour for the benefit of that community. Likewise, the finds remind us that certain people organised this exclusion and exploitation and thus became perpetrators. A very large number of Germans consciously profited from forced labour.

However, the archaeological sources cannot bear witness directly to either the actions of the perpetrators or to the experiences of the victims. The potential of the objects lies rather in the fact that their presence confronts us with the history of the camps. Their specific materiality enables an unusual, nonlinear approach to history (Korff and Roth 1990, 15). In addition to their scientific quality, the finds also have an emotional quality, as they are directly connected to people and their fates (Bernbeck (2017, 95) notes their potential for evocation). The fact that they disappeared into the earth for a long time before being found again adds layers of meaning of forgetting and remembering to them. This generally distinguishes them from the many objects in the memorial magazines that were never stored in the ground. Ronald Hirte (1999, 77) puts it this way: 'By finding, recovering and preserving, that is, by perceiving the things, the devalued objects are given back some of their dignity, the symbolic annihilation (Assmann 1995, 12) of them is undone to some extent. In this respect, the process of excavation is in itself a form of commemoration'. The finds do make the place visible again, and thus also the victims and the perpetrators. They vouch for the conditions and the people who experienced them. This aspect is one of the most important functions of these archaeological sources (Bernbeck 2017, 11, 131).

The 'open-endedness of meaning of things' (Drecoll 2017, 110) entails the risk that the 'things' will be interpreted differently. Archaeology for its part, cannot provide definitive answers. It embarks on a search for clues and tries to identify indications of the function and use, context, and production of the finds and to develop an eye for details. In the process, it also becomes clear that archaeologists do not (yet) know much about the people in the camps or about the camps themselves. Thus it is a matter of 'extracting' the 'stored knowledge' from the objects (Keller-Drescher 2010, 243). Their significance lies in the historical event to which they refer, not in themselves because 'remnants exhibited as sources can easily become relics', and 'objects cannot narrate, they are rather occasions for narratives' (Hoffmann 2007, 208). They do not speak to us of their own accord, but they can be made to tell their stories (Loistl 2016). They testify just as much about perpetrators or profiteers as about victims. They cannot always be clearly attributed; it is impossible to say with certainty whether a spoon was used in the camp by a guard or by a forced labourer housed there. Because it was found in a camp, it points to the existence of the camp and to the different living conditions of the people in it. Other things are more clearly identifiable by the way they were made or by their marking, for example with a prisoner number.

In contrast to those in the depots and collections of the memorial sites and museums, the excavated finds have survived by chance. They have not been given to the memorial sites by contemporary witnesses or their descendants, nor have they survived in the memorial collections of things taken away from the prisoners (Schulz and Rositzki 2021). All the found objects are or were buried in the ground as rubbish and forgotten. Their selection is associated with the 'rubbish phase', i.e. the process of being thrown away (Ludwig 2015, 432). They did not seem worth keeping after the liberation of the camps. This is precisely what makes them special today: 'For the objects recovered from the earth receive special attention precisely because of their temporary, often long-term disappearance and reappearance. They are alienated because, as a rule, … [they are] fragmented' (Bernbeck 2017, 193). The salvaged things are marked by their use and survival in the earth. Precisely because they look different from when they were in use, they reveal their historicity and refer to individuals through their material properties, traces of use, and modes of function and use (Ludwig 2015, 444). Handmade objects - and many industrially produced things - were created, used, transformed, or marked by specific people, either an individual or several individuals in succession or simultaneously. The objects are more than artefacts; they had a 'social life' (Ludwig 2015, 438). Carr (2018, 533) provides an instructive figure that clarifies the 'value' of the finds, which varies from practical to economic, from scientific to commemorative value.

Many items are mass-produced industrial goods, which initially can barely be dated more precisely than the mid-20th century and often even the determination of industrial semi-products is difficult (Poggel 2020, 11). This has resulted in such finds only being recovered in (small) numbers, almost as 'voucher pieces' and pars pro toto (Bernbeck 2017, 133). That masses of people were kept in the camps, either at the same time or sequentially, does ensure 'find masses' (Theune 2015, 37), however. Still in full operation at the end of the war, the camps and everything in them were often levelled shortly afterwards; inventory, accessories, and rubbish were deposited below ground and thus 'archaeologized' (Theune 2015, 39). In most cases, excavations have placed and continue to place a very strong emphasis on individualised and/or homemade or adapted pieces. These are undoubtedly archaeologically recovered historical testimonies of the highest value, but the other mass-produced items do have a high potential for analysis if they are excavated as is customary for objects from other periods, i.e. all of them are excavated and 3D measurements recorded. This was not feasible with the excavations discussed in this article, almost all of which were undertaken as part of rescue archaeology projects under construction site conditions, owing to limited personnel and capacity of the museum storage facilities (Müller 2010). However this should become common practice (Bernbeck 2017, 100). The potential of single-find mapping became visible in the excavations of Reinhard Bernbeck in Berlin-Tempelhof; the analysis will probably continue for a long time, but it has shown some promising initial results (Bernbeck 2017, 35, 283; Theune 2015, 41).

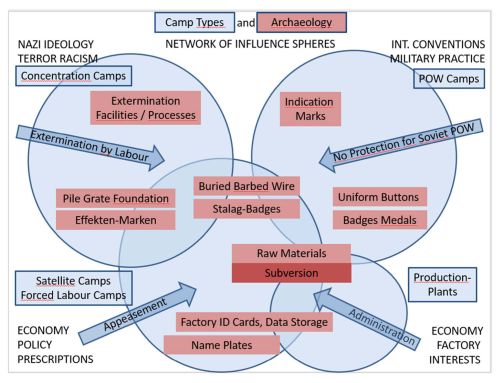

The question of the function of material remains i.e. archaeological finds and features, in relation to the different camp types is a salient one. Are there finds and features that are characteristic of concentration camps and their satellite sites, forced labour camps, and prisoner-of-war camps? Archaeological investigations at sites of all such camps have produced substantial assemblages, even if none of the sites could be investigated completely. Among the features and finds encountered, some are ubiquitous. In the former category, for example, are the remnants of barracks, sanitary areas, water supply and waste disposal systems, infrastructure, and fences; the latter has canteen and enamel dishes, military eating and cooking utensils, combs, makeshift self-made items, and souvenirs or mementos from home, as well as all kinds of sheet metal tags.

Features attesting to racist practices are of special interest among the archaeological remains. These are:

Objects that indicate the differential treatment of people are often found too. A wide variety of sheet metal stamps of all kinds, bearing numbers and names, are considered typical camp finds (Hausmair 2018). They can be specifically assigned a function of oppression and alienation if they are stamps that inmates received as 'receipts' for handing over all their belongings ('Effektenmarken'). Such stamps have been found in concentration camps (Sachsenhausen) and in forced labour camps (Rathenow, Treuenbrietzen, Hohensaaten, Germendorf, and Brieskow-Finkenheerd), but not in any prisoner-of-war camps, where people apparently kept the things they brought with them. Tin badges that are official military identification badges (associated with soldiers from all of the Allied countries except the Soviet Union), on the other hand, have been found in the large main camps of Frankenfelde, Eisenhüttenstadt, and Mühlberg (buttons from the uniforms of foreign soldiers are also found), but not in other types of camp. So-called stalag badges, issued by the Wehrmacht as military identification tags for captured Soviet soldiers, have been found wherever those soldiers were present: the large prisoner-of-war camps, the concentration camps (Sachsenhausen) and the forced labour camps (Rathenow and Hohensaaten). Handmade, decorated tin nameplates of French prisoners, sometimes with stalag numbers, seem to be specific to the Rathenow forced labour camp, although very similar name plates have been found in the Mauthausen concentration camp (Hausmair 2018). Objects pointing not to the treatment of people but to their activities are raw-material remains from the workplace. Mostly made of metal originating directly from the production process, these were found primarily in forced labour camps (Rathenow, Kleinmachnow, and Treuenbrietzen) associated with factories. Objects made from such remains, on the other hand, can be found practically everywhere. Name-bearing 'storage media' metal plates have only been found in the forced labour camps associated with large armament factories (Treuenbrietzen and Brandenburg-Neuendorf), or more precisely in the administrative areas of these factories. The same is true of access-authorising factory ID cards, which have only been found so far in a waste disposal area near Rathenow.

In this context, the meaning of material remains can be determined when they are quite typical of certain categories of camps, such as traces and remains of extermination facilities and processes (for concentration camps), identification marks (for prisoner-of-war camps), and data storage or access authorisations (for forced labour camps associated with large factories, especially the production and administrative areas). On the other hand, specific material remains are often those that mark groups of people, reflecting their exposure to different spheres of influence such as Nazi racist ideology, military practice and international conventions, economic interests, and policy prescriptions. At the same time, there are material residues that arise from the self-interest of groups of people such as (1) the racist intention of exclusion and extermination (evidenced by barbed wire, stalag marks, and pile grid foundations), combined with minimising expenses for economic reasons, which affected the treatment of Soviet prisoners, who were not protected by any international convention (later the Italian military internees would likewise lack protection); (2) the intention to record and administer (expressed in the data storage by means of the ADREMA boards and the authorisation of access by means of factory passes), which affected all those working for a larger company, even those forced to so; and (3) the intention to survive, which becomes visible in the diversion or theft of material and production remnants for adaptation and reuse, which spread subversively from those who had access to the material.

So, at last it is specific groups of people who become visible via the archaeological inventory of the various camps, such as Soviet prisoners of war and 'Eastern workers'. These particular groups were not mobile, yet were not associated exclusively with a particular camp type. Their presence is indicated by specific structural interventions (pile grid foundations, buried barbed wire) and portable items (stalag marks). Other excluded groups become visible through their interest-driven actions, particularly those associated with a high degree of risk, which left behind specific find materials (Figure 16).

Based on a material-based categorisation of the find spectrum, Table 1 shows the association of finds with different functions in the camps. This is almost always possible with finds produced in the 20th century, unlike with prehistoric and early historic finds. For the functional categories of buildings/furnishings, food, personnel hygiene, clothing, guarding, and burial, there are usually no problems of attribution. It is different with personal objects (cf. the 'accessories' category in Müller 2010, 129). Such items (e.g. whistles, tobacco pipes, house keys, (pocket) knives, toys, figurines of saints, and jewellery) originally had a wide variety of functions. In the camps, however, they probably lost these functions for the most part and acquired a new one, that of being a token of an alternate reality, of home, of the past, of normality, even of the future. A comparable transformation must have occurred in the case of objects associated with factory production that were recovered in the camps: these were probably stolen and then repurposed. To this end, they were adapted more or less skillfully - often quite professionally - in the workplace where tools were available.

| Materials and functions | Ceramics | Glass | Metal | Plastic | Other (wood, bone, stone, etc.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building accessories and furnishings | pipes, sanitary tiles, insulators, electrical | windows, lamps, mirrors, air shelter door, ink containers | nails, hooks supports, holders, installations, furnace parts, handles, binders, hangers, locks, keys, pendants | lamps, switches, office objects, stencil, extinguisher, rollers | barrack parts, insulation, coal |

| Food preparation and reception | crockery, porcelain, stoneware, adaptations | bottles | canned food, kitchen and tableware, cutlery, cups, funnels, sugar cans, adaptations | flask cups, butter dishes | wooden and bone spoons adaptations |

| Personnel hygiene and medicine | pharmacies, vessels, dental ceramics | vials, ampoules, mirrors, glasses, adaptations | shavers, tubes, tins | glasses, fittings, dentures, combs, toothbrushes, shaving brushes, soap tins, adaptations | bone spoons |

| Clothing, footwear | buttons, badges, uniform parts, shoe sole, boot heel, fittings | buttons, badges, shoe sole, adaptations | buttons, shoe leather clogs adaptations | ||

| Personal items, souvenirs | game pieces, carvings of names and symbols, adaptations | game pieces, jewellery, church mosaic, adaptations | boxes and plates with numbers, names and symbols, saxophone, church chalice, adaptations | containers, detonator boxes, souvenirs, adaptations | game pieces, souvenirs, tobacco pipe, musical instruments, adaptations |

| Manufacturing | shards as cutting and scribing tools, adaptations | tools, semi-finished products, sheet metal cuttings, solder wire, adaptations | plexiglass protective goggles, ID cards, adaptations | sewing tools, accessories, (Schneider-Kreide) | |

| Guarding | ammunition, weapons (parts), badges, billets, gas mask parts, | badges uniform parts | |||

| Burial | urn tags | urn lids | human remains |

This dimension of a functional change under conditions of bondage and scarcity for the purposes of everyday camp life is a characteristic of Nazi camp finds that is probably without parallel. On the one hand, unchanged objects would be charged with new meaning as souvenirs and, on the other hand, objects were adapted for the purposes of everyday camp life. It is this phenomenon of a functional 'shift' that is described, for example, by Bernbeck (2017, 201) as 'misappropriation' and then as 'affordance'.

It should be borne in mind that many people working under duress crossed a barrier twice a day, depending on where they were working, between state-of-the-art workplaces of the mid-20th century (marked by a highly efficient work economy and high-tech materials such as Plexiglas and Dural-Aluminium that had only just been developed) and living environments that were often downright archaic in their primitive conditions. Here the most basic necessities were lacking, including physically vital things such as spoons, bowls, cups, and funnels to catch water, but also things related to the playing of games, the practice of religion, and the creation of symbols, pictures, and initials that enabled the spiritual-emotional survival of a person's identity. Both, however, could be made from factory production leftovers. Therefore, subject groups with the occurrence of adaptations are highlighted in the table. In some instances, one not only possesses souvenirs 'of earlier, of home', but also creates souvenirs of the deprived present, the camp time, possibly to assure oneself of the hope of an end. Table 1 thus shows materials and their functions with a further level of division into original objects of industrial production versus self-made or adapted objects. There is another level to be considered here: namely the spheres within which the users of such objects existed.

Table 2 builds on Table 1 definitively assigning material remains (both finds and features) based on their functions to different spheres of life in the camp, following the approach of Carr (2018, 539). Here it is taken into account that in and across these spheres of life there are also different actors of the camp society i.e. those who exercise agency in relation to the objects (material remnants) as subjects. These people are divided into two groups; the perpetrators (guards/operators) and the victims (prisoners/inmates) (Theune 2015, 37; Carr 2018, 539). The identification of victims who became perpetrators (e.g. kapos) cannot be made on the basis of the archaeological material, but this transformation should of course be considered. Practically all archaeological phenomena - traces, finds, and features - can be categorised and assigned to four broad types of function that in turn are associated with six spheres of life: administration, catering, provisioning, reassurance, exploitation, dissolution. In all of the spheres of life mentioned, both the perpetrator and the victim groups were actively involved or passively affected in very different ways and to different extents. Archaeological evidence has been found of the presence of both groups in each of the spheres.

| a. Administration: infrastructure, equipment, guarding, violence | b. Catering: rations, nutrition, intake, distribution, shortage | c. Supply: clothing, body care, hygiene, medicine | d. Reassurance: self-assertion, identity protection, quality of life, demonstration | e. Exploitation: production, profiteers, adaptations, parallel worlds | f. Dissolution: hope, liberation, extinction, memory | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Offender group guards, operators finds and structures | construction building parts, installations, killing and burning, fence lock, key, office folder, ID card, numbers, weapons, gas masks | kitchen fixtures and equipment, tableware, porcelain and canteen dishes, animal bones | pharmacy and medicine vessels and equipment, uniform and boot parts, fittings, belt gear | state symbols, insignia, military/SS insignia, company logos, demonstration of group identity, "Volk" and "Gefolgschaft" | tool products, signs, badges, manufacturer inscriptions, mass findings, semifinished products | bomb damage, glass melting, leveling layers, garbage pits, ashes |

| B. Victim group inmates forced labourers finds and structures | racially graded construction, quality, internal demarcation, ADREMA boards, ID cards, human ashes | canteens and tinware, cutlery, including that adapted from factory production remnants, animal bones | heating and sanitary infrastructure present/ missing, medicine, perfume, combs, buttons, toothbrush, soap box, razor | inscriptions, name plates, initials cast in asphalt, souvenirs, self-made identity card covers, hiding places demonstration of individuality, belonging and subversion | adaptations of high-tech production leftovers for everyday purposes | splinter trenches, symbols of the liberators (Soviet star), torn identity cards, souvenirs of the camp period |

This category includes all construction features and finds of building parts and installations, including killing and incineration facilities (shooting trenches, gas chambers, crematoriums); office equipment such as files, data carriers, and identity cards and numbers; the guarding complex, consisting of fencing and locks/keys; and the apparatus of violence, including truncheons, weapons and ammunition, and gas mask remains. By their very nature, they can all be attributed to the perpetrator community. However, they have an effect on the victim group, especially in the form of the racially graded construction quality and the data collected and used without consent, as well as the forced allegiance to the production companies. Carr (2018, 539-40, categories 4 and 5) calls attention to the fact that many find categories will affect both groups of 'actors' in the camps.

In their external structure, the forced labour camps resembled each other (Haubold-Stolle et al. 2020, 58). The areas of the concentration camps, POW camps, and camps for Soviet and Polish civilian forced labourers were fenced in. Barracks stood along camp roads and there were places for assembly and functional buildings, such as camp administration offices and usually a prison. The Reich Labour Service (Reichsarbeitsdienst) made use of various shapes and sizes of barracks, which were supplied in more or less standardised forms by a wide variety of manufacturers. Often state authorities gave or rented barracks to the companies (Baganz 2009, 254). They consequently saw widespread distribution. But on the other hand, there were major differences. A concentration camp was a heavily guarded place of detention ringed by electrified barbed wire fencing, so that escape was virtually impossible. Camps for Eastern European forced labourers or Italian military internees were also enclosed within barbed wire fencing (Baganz 2009, 251) and guarded, whereas those for Western Europeans were not. Their residents were free to move around the adjacent town or city after work. When several different groups were housed in one camp, internal demarcations (which have been confirmed through archaeological investigation), ensured that the 'racial hierarchy' was maintained. Not only did the degree of guarding differ, but so did the type of construction, the furnishings of the barracks, and the number of people housed within specific areas of the camp with distinctions being made in accordance with the racist guidelines of Nazi ideology. Western European and Czech forced labourers and prisoners of war were housed slightly more comfortably than Polish prisoners of war and forced labourers. Soviet prisoners of war often had to live in unheated barracks, with even poorer quality insulation and even foundations than those of the barracks for other types of prisoner.

The identification and administration of prisoners in the camps was done by means of numbering. Soviet prisoners of war were given stalag tags (Figure 17), which were identification tags with a serial number and the identification number of the Stammlager in which they were first imprisoned. Officially, the Wehrmacht tried to comply with this regulation, at least for the Western European prisoners of war. Soviet soldiers were not always registered, but when they were, one can sometimes locate the corresponding file card and photo on the internet on the homepage of 'memorial.ru' using the number on the tag (Haubold-Stolle et al. 2020, 68). Civilian forced labourers were usually registered with an identification number on arrival, but this was not recorded nationally or centrally, or their data were stored by means of so-called ADREMA (Adressiermaschine) boards (Figure 18). In the concentration camps, the concentration camp number replaced the name of the prisoners, who were thus deprived of their identities. Everything was numbered: people, personal effects, barracks, rooms, lockers, beds, etc. (Stencils also appear in the finds material, as they were needed for proper labelling. A look at a photograph of a barrack for 'western workers' of the Arado factory shows an extensive ensemble of objects (Bauer et al. 2004, 125): lampshades, earthenware and porcelain bowls and mugs, cooking pots, lids, ashtrays, glass bottles, coat hangers and hooks, locker signs, metal beds, suitcases, and various other items).

The finds of recent archaeological investigations at Nazi forced labour camps also include weapons and ammunition remains as well as other crime tools and evidence including human remains (Theune 2018, 24). Excavations in a former concentration camp always take place at a crime scene, which is also often a mass grave. In and above the earth are the ash remains, bones, and skeletons of the people who were murdered in the camp. This fact fundamentally distinguishes concentration camps from other forced labour camps. Other finds also point directly to the bodies and suffering of people, such as bits of dentition from the rubbish pit of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

Other direct evidence of crime is shown in the permanent exhibition of the Sachsenhausen memorial: the cartridge drum of a machine gun, which comes from the Lieberose subcamp near Jamlitz and is evidence of the shooting of the Jewish concentration camp inmates when the camp was shut down. The gas mask rings from the killing centre Altes Zuchthaus in Brandenburg an der Havel point directly to the murder of sick patients by poison gas (Haubold-Stolle et al. 2020, 129). The gas masks were worn by those who examined the bodies after the murder and carried them out of the gas chamber. But archaeologists have been confronted with evidence of crimes against humanity in forced labour camps as well. The truncheon or club, such as the one found in Falkensee (Haubold-Stolle et al. 2020, 128) is frequently thematised as a symbol of oppression and humiliation in contemporary depictions of prisoners (Morsch and Ley 2016, 32, 43) and guards can also be seen posing with it in photographs.

Evidence of the perpetrator group's food consumption includes finds such as kitchen fixtures and utensils, cutlery, porcelain and canteen crockery, and occasionally animal bones, as at Berlin-Tempelhof (Bernbeck 2017, 348). In the case of the victim group, the focus is more on the absence of food remains as well as objects related to consumption, distribution and serving e.g. different crockery, a canteen (Figure 19), tinware (Figure 20), and cutlery fabricated out of factory production remnants (Figure 21). Efforts to supplement the diet can be documented in places on the basis of animal bones (Müller 2010, 109; Carr 2018, 539, category 3).

Many of the archaeological objects found in Nazi forced labour camps were related to the preparation or consumption of food (Haubold-Stolle et al. 2020, 70). In most camps, food was prepared centrally in a kitchen and then distributed to the individual barracks or housing units. Not surprisingly then, large pots and other cooking utensils have been recovered during excavations. Soups were the basis of nutrition in the camps. These could be made in large quantities with just a few ingredients and diluted with water. It was vital for all camp residents and prisoners to have some object in which the daily food ration could be received, especially cups, plates, regular bowls, or soup bowls. The fact that the camp operators often had to improvise in order to feed large numbers of people is reflected in the large number of different 'dishes' found. Canteen crockery can also be found in the camp areas alongside colourful enamelware, aluminium vessels, and partially modified military eating utensils.

Contemporary photos also illustrate this. In barracks in Sachsenhausen, photographs show prisoners eating from porcelain bowls and cooking pots (Morsch and Ley 2016, 145), and in a women's camp in Brandenburg an der Havel, at least four different kinds of eating bowls can be seen on the tables (Bauer et al. 2004, 120). From the visibly brand-new furnishings in a bright, new building, one can see that this duality prevailed right from the start. Containers of all kinds were a kind of life insurance because with them one was able to receive, store, and carry food and drink. For security against theft (and probably also for comfort), they could be placed upside down under the head as a kind of pillow when sleeping, as a photo taken after the liberation of the small camp in Buchenwald in 1945 shows (Stein 2014, 239, fig. 244).

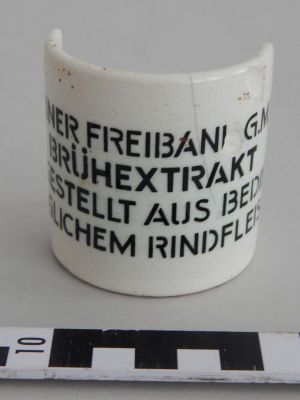

All people living in the forced labour camps were inadequately fed. Depending on the camp and a person's status - concentration camp prisoner, POW, or civilian forced labourer - different food rations were distributed. Distinctions were also made on the basis of a person's national origin. The Nazi racial ideology had an effect here: Western European forced labourers (e.g. from the Netherlands), who were at the top of the racial hierarchy, received better and more food than the so-called 'Eastern workers', who themselves received more food than Jewish concentration camp prisoners and Sinti and Roma, who were at the lower end of the 'racial scale'. In some camps, prisoners made their own scales to weigh the bread or rations against each other and to compare them. Such pieces are missing from the assemblage from Brandenburg State (i.e. they have either not been found or have not been positively identified as such), but several have survived from Buchenwald (Stein 2014, 182, fig. 169), one possibly made from a wooden clothes hanger. Officially, the rations were fixed. However, this says nothing about the actual condition of food in the camps. Often low-quality food was provided, food was stretched with fillers, and the regulations concerning the number of calories were not followed. On other days, the food was spoiled or riddled with maggots or worms. It also happened that allotted rations were not distributed to the camp residents, but were embezzled by the camp staff and sold to privileged persons in the camp. The use of low-quality Freibank (cheap meat counter) meat was included in the official ration prescriptions for 'Eastern workers' (Baganz 2009, 263), as finds from a camp in Basdorf demonstrate (Figure 22).

Soup was the main food, and small amounts of bread and other additions were provided, depending on the camp. In 1943, performance feeding was introduced for Eastern workers, Soviet prisoners of war, Italian military internees, and concentration camp inmates. This meant that food was distributed according to work performance. Those who worked more got more food and those who worked less got less food. This created a vicious cycle in which those who could work only a little, due to illness and weakness, were weakened further, which not infrequently resulted in death by starvation. Hunger was a result of efforts to discipline inmates as well as to cut costs, with deprivation of food being a frequently imposed punishment. Hunger was also a method of murder: in the Ravensbrück women's concentration camp and in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, thousands of prisoners died from malnutrition and its consequences. Soviet prisoners of war in the camps in Luckenwalde and Fürstenberg were also so poorly fed that thousands of them died from hunger.

The perpetrator group had access to heated sanitary areas plus pharmacy and medical facilities with the typical vessels and equipment, which also found their way into the camp area of the victim group. Significantly, a rare single find of a boiler at Mahlow was preserved in situ because of its further use there after the war (Haubold-Stolle et al. 2020, 210). The perpetrators owned uniforms and boots, all kinds of fittings from uniforms and belt gear, which, when found vary from new and unused to detached and discarded. The victim group is also defined structurally according to whether heating and sanitary facilities were available and, if available, what level of quality characterised them. In cases where no sanitary facilities existed, however, finds of medicine and perfume bottles are not uncommon. Buttons, combs (new and self-made), toothbrushes, soap tins, and razors, are standard finds and all fall under category 2 as defined by Carr (2018, 539) .

In all the forced labour camps, including those for Western European prisoners of war, far too many people lived in a confined space (Haubold-Stolle et al. 2020, 94); there was no privacy. The occupancy of a stalag was regulated by the Wehrmacht: the planned maximum occupancy was 10,000 men, with camp sub-sections to have a capacity of 1,000 people, and 380 people were to be housed in a single barracks with two sleeping rooms and a central washing area. Most prisoners of war remained in the stalag for only a few weeks, after which they were assigned to one of the numerous work units outside the camp and housed there in forced labour camps, which varied in both size and degree of confinement.

Because of the conditions, diseases spread quickly, and the lack of sanitary facilities greatly increased the risk of illness and death. In the forced labour camp no. 75/76 in Berlin-Schöneweide, one of the smaller barracks had 2 toilets and a pee wall for 160 men. In the Ravensbrück women's concentration camp, 8 toilets for 100 women were originally planned, but the number of women housed in the barracks increased so drastically over time that 500 women were crammed into a single barracks by the last weeks before liberation. This meant that every day the women had to fight for a place at a washing facility and toilet in an enormous scrum. In provisional camps, such as the one in Below Forest, during the Death March of concentration camp prisoners at the end of the war, or in transitional camps for Soviet prisoners of war, toilets and fresh water were completely lacking.

With little water and hardly any allocation of soap and washing powder, hygiene was predictably a problem in all camps. Within the construct of the Nazi social order, cleanliness was seen as a sign of superiority and 'Germanness'. In this context, the refusal to give people in the camps the opportunity to clean themselves regularly and thoroughly can also be understood as intentional. Many camp residents felt the enforced uncleanliness as a particular humiliation. Another consequence was the infestation of vermin: lice and bed bugs were not only unpleasant, but also transmitted life-threatening diseases. The matter of keeping clean and well-groomed was also a matter of staying alive. This was true even for those who did not die directly from one of the diseases because anyone who fell ill in a forced camp could not work. Yet this was also life-threatening for forced labourers under National Socialism. Those who were unable to work were threatened with death. In the concentration camp this was either by the gas chamber or shooting, whereas civilian forced labourers were killed in the context of the 'sick killings' at a medical clinic or through neglect leading to death in a sick camp such as those in Berlin-Blankenfelde or Mahlow.

Among the perpetrators, military insignia of rank and SS symbols, flags, and state and party emblems were omnipresent. The insignia of the factory owners and company logos could be seen everywhere, right down to the identity cards and work books. Such demonstrations of group identities, in this case of the SS and the Wehrmacht, of the German 'people', and of company 'followers', could not be escaped by the victim group anywhere, except perhaps temporarily in the barracks. The name inscriptions that the members of the victim group made in secret as portable objects (e.g. their homemade name plates) or inscribed onto immovable structures (in the form of Cyrillic initials pressed into the asphalt in the latrine in Eisenhüttenstadt) seem to act to counteract this. Their souvenirs and hiding places also are demonstrations of individuality that signal subversion. At the same time, homemade identity card covers, for example, express the need to belong to specific working groups, even though initially forced labourers had no choice in the matter.

Additional evidence of the demonstration of power includes the frequently encountered horseshoe-shaped iron boot heels, which meant that marching troops could be heard from afar. The fear felt when hearing the sound of boots hitting the pavement is a recurring motif in many accounts by contemporary witnesses. In a possible historical narrative based on acoustic evocation, this sound is contrasted with the clattering of the prisoners' clogs, which is also reported, and with the noiseless rubber soles of the US troops, which were noted by German people with alienation. In a forced labour camp, prisoners were part of a mass and were expected to feel that way (Haubold-Stolle et al. 2020, 110). Individuality and self-worth were taken away from them, in part to make resistance more difficult. They were reduced to their working power and had to work for the 'German victory'. However, numerous finds from the camps that fall into Carr's category 1 (2018, 539) document the will of those imprisoned to assert themselves and remain more than a number. Most striking are objects bearing initials or names. The inscriptions identify possessions, mostly items used for food consumption. These were indispensable because the longer the war lasted, the more difficult it was to obtain even the simplest everyday items such as cups and mugs in a camp. At the same time, being able to read one's own name also strengthens one's identity.

Possession of something, however minimal, gave prisoners a little space for self-expression. Furthermore, making things that were needed eliminated scarcity. For example, one could comb one's hair and remove lice with a self-made comb. Handmade things could also be given as gifts and thus bring joy to someone else and strengthen a human relationship. Acts of solidarity and friendship between prisoners were themselves modes of resistance in a concentration camp (Bernbeck 2017, 204), as the camp administration set out to control the prisoners by inciting competition among them and playing different groups against each other. Friendships were also crucial for the survival of prisoners of war and forced labourers.

At the same time, self-made things were objects of exchange. People traded woven baskets or other 'handicrafts' they had made outside the camps for food (Hirte 1999, 40). To make things, camp residents and prisoners resorted to what they had: wood taken from bed frames, paper or straw from the bed sacks that served as mattresses, or colourful toothbrush handles, which were used to make many miniature objects in the women's concentration camp of Ravensbrück, for example (Beßmann and Eschebach 2013, 161). Factory production leftovers or materials from the workplace were also used for self-made things (Figure 23, Figure 24). Stealing and processing these materials was risky, as such actions could be considered sabotage and thus punishable by death.

Another way to assert one's self in the camp was to decorate things or make objects of beauty. Both set the camp existence against the memory of a better world. Culture, most often in the form of music, education, and religion could also strengthen prisoners' sense of self. Engaging in cultural activities was forbidden in the concentration camp, but was nevertheless sometimes tolerated. Secret lectures, school lessons for younger prisoners and children, musical evenings with singing or even instruments stolen from the personal effects room not only passed the time, but demonstrated to the prisoners that life existed beyond the camp. Religious services were also celebrated in the concentration camps (Haubold-Stolle et al. 2020, 122). Communal and individual acts of faith could support the will to live of prisoners and forcibly displaced people.

Prisoners of war were entitled to pastoral care and cultural activities according to the Geneva Convention, however this did not cover Jewish prisoners of war and Soviet soldiers, however. Consequently British, French, and American prisoners of war were allowed to set up chapels in their barracks and celebrate religious services. For example, in Stalag III B in Fürstenberg there was one chapel for French prisoners of war and one for the Americans. The Americans' chapel was located in a barrack with a lending library, a theatre room, and an athletic training room as well. The prisoners made the furnishings (and a mosaic, as found in Eisenhüttenstadt) mainly out of rubbish. The better treatment of Western prisoners of war compared to that of Soviet prisoners of war must be acknowledged, but that should not lead to the evaluation of their captivity as 'less bad'. Western prisoners of war were also completely subject to the arbitrariness of the Nazi regime.

The finds associated with the perpetrators and profiteers include things that are directly related to factory production, such as factory-made tools and industrial products or parts of both. Large numbers of these types of artefacts were recovered during investigations recently carried out at two sites, the Dreilinden plant in Kleinmachnow (Antkowiak 2020) and the Arado plant in Rathenow (Bartels 2021). In addition, there are signs, identity cards, manufacturer inscriptions, and mass finds of semi-finished products from Ravensbrück and elsewhere. The victims' group, in this context, are above all associated with adaptations of remnants of materials (taken from the factories) for everyday uses in their often-primitive archaic environment, a parallel world to the modern industrial workplace of the 20th century. It was the use of unskilled workers that forced the factories to rationalise and thereby contribute to the 'economic miracle' after the war and to the modernisation of German industry as a whole (Bräutigam 2003, 28).

Many things recovered from the sites of forced labour camps point to profiteers (Haubold-Stolle et al. 2020, 124). First of all, this group included the companies that used forced labourers. Forced labour camps were usually located in the immediate vicinity of factory production sites and, with the increasing relocation of armament production, in the Berlin environs. The manufacturers' names on canteen crockery and cutlery remind us of the profit the companies made from forced labour and of their responsibility for the treatment of the forced labourers (Bernbeck 2017, 150). But those who built and supplied the camps also profited. The provision of beds, crockery, water-supply and sewage pipes, the administration and rental of barracks, and the construction and operation of camps, formed a business in and of itself. In the course of the war, the worsening labour shortage caused German industry and the state to rely on forced labour more and more. In addition to prisoners of war and deported civilians, concentration camp prisoners were also used as the last reserve of labour. Either concentration camp satellite camps were built adjacent to the forced labour camps at armament production sites and large construction sites or the companies built their production facilities directly next to the concentration camps, as Siemens and Halske did with Ravensbrück, the women's concentration camp. Ultimately, however, the entire German population profited from the exploitation of the people in the camps. Forced labour produced not only armaments essential to the war effort, but also food and consumer goods for the Wehrmacht and the civilian population. There was no area of work in which forced labour was not used. Without it, the war could not have been fought for so long. Moreover, without forced labour and the plundering of the occupied territories, it would not have been possible to provide for the German population during the war.

The everyday objects found at the camp sites and associated with the German camp administration and the German workers show that forced labour and 'normal' working conditions existed side by side. The finds indicate that the Germans were better provided for, but also show that the forced labourers were not segregated from German workers. The archaeological findings cannot speak to how the colleagues, administrators, and guards behaved towards the camp residents and prisoners. Here we have to rely on the statements of contemporary witnesses, who report a wide range of behaviour. In addition to isolated acts of compassion and humanity, there are reports of violence, assaults, and degrading treatment, even on a small scale. The vast majority of Germans, both workers and civilians, however, were simply indifferent to the suffering of the forced labourers and concentration camp inmates.

As the war was coming to an end, both the perpetrator and the victim groups were affected by aeroplane bombing, of which the archaeological traces are the debris and remnants left behind, such as molten glass. For the victim group, mostly completely inadequate sliver trenches were provided as protection. These have been archaeologically investigated to some extent. Handmade symbols of the liberators such as Soviet stars and a hammer-and-sickle motif made of sheet metal testify to the hope of liberation (Figure 25). Torn factory ID cards from Rathenow may document the relief at liberation. Many prisoners took home souvenirs from the camp period, often to be given later to the memorials at the camp site. Other souvenirs were left behind, such as the Plexiglas 'Souvenir de ma captitivité' which was left behind by a French POW in Luckenwalde (Figure 26). There are striking parallels to the symbols of hope among finds from German internment camps on the British Channel Islands, in which the 'V' plays a role as the 'Victory sign', whether carved, painted on, woven in, cut out, to give some examples (Carr 2010).