Cite this as: Konik, J. 2024 Underground City: archaeology of the Warsaw ghetto in its academic, memorial and social context, Internet Archaeology 66. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.66.16

Does the archaeology of the Warsaw Ghetto differ from the archaeology of any other large, busy city? The answer is: yes and no. In some aspects, the difficulties encountered by a Ghetto researcher are typical of urban archaeology in general: solving problems with different offices of the city administration, obtaining permits, planning logistics to ensure the unhindered traffic of cars and pedestrians, gaining the approval of the local residents etc. On the other hand, however, the archaeology of the Warsaw Ghetto has a variety of issues absent from other similar research sites. Modern Warsaw is built on the rubble of the ancient city that was almost completely destroyed by the Nazis during World War II. The invaders left the Polish capital in ruins, and there was so much debris that its removal was often abandoned. Thus, its layers formed a base for many buildings of contemporary Warsaw. This is especially true in the area of the former Ghetto situated in the very centre of Warsaw, where most of the Jewish population lived before the war and where all the Jewish residents were enclosed in 1940. After the Ghetto Uprising in 1943, all the buildings of the Jewish district were razed to the ground by the Nazis (Stroop 2009). After the war, c.3 million cubic metres of rubble covered the area. When a new housing estate was planned to be erected there, its architect, Bohdan Lachert, decided to build it on the rubble and out of the rubble using rubble-concrete blocks, as he wanted to make it a kind of memorial to the murdered Jews (Chomątowska 2012).

In this way, the post-war rebuilding works created another, lively and dynamic city on the remains of the ruined one. It can be said that contemporary Warsaw consists of two cities: the one you can see, and the other underground (Engelking and Leociak 2013), although despite the apparent wealth of written and iconographic sources, we actually know very little about the latter. Thanks to archaeological research, this knowledge is gradually growing. At the centre of this 'double city' space, there is the Warsaw Ghetto, a small area where almost every stone could be a memorial monument, and where any archaeological find immediately acquires symbolic significance. Such an emotional load implies certain consequences for the researchers, who have to treat their place of work with special care.

While working in the Jewish residential quarter, where fighting during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising took place, we also had to pay special attention to the religious requirements of Judaism, because of the human remains that could be found in the area. The approach to dealing with the remains of the dead is restrictive in that they must not be moved from the place where they were buried, especially difficult in the case of mass graves when it is impossible to distinguish between the deceased. The specificity of the excavation site required us to cooperate with the Polish rabbinical commission and to be very careful with the bone finds.

Another important issue in the Ghetto area is the social reception of the research (Pawleta 2020). The archaeological team enters the area with its new, post-war layout, and social organisation. Bringing to light the pre-war 'underground city' disturbs this contemporary space and its rules in a way, especially given Polish-Jewish relations before, during and after the war, which are complex and evoke many emotions. Archaeologists therefore are also responsible for explaining their activity and gaining acceptance from members of the local community, achieved in this case thanks to our 'open door' policy during the excavations. Everybody could come to the excavation site through the open gate and ask questions. This required some extra effort from the archaeologists, but in the long run resulted in the positive attitude of the local residents.

Archaeological research in the former Warsaw Ghetto conducted in 2021-2022 was a joint venture undertaken by the Warsaw Ghetto Museum and the Aleksander Gieysztor Academy in Pułtusk (a branch of the Vistula University), with support from Prof. Richard Freund's team from Christopher Newport University, US.

This was a breakthrough in academic research on the Ghetto and the Shoah in Poland because the area of the former Warsaw Jewish quarter had never been archaeologically investigated in a systematic and planned manner. Previous archaeological activities were undertaken because of developments planned in specific locations, such as the explorations by Martyna Milewska in 1998 and 2009 that preceded the construction of the Polin Museum (Cędrowski 2009; Frączkiewicz 2021), or the works in the Krasiński Garden led by Zbigniew Polak in 2013-2014 (Polak 2014). No doubt the archaeologists conducting these projects had vast experience and appropriate competence; however, they did not have any specific research programme related to the Warsaw Ghetto, its history or the earlier, interwar, and even the 19th-century history of the so-called Northern District.

The idea of the extensive research dedicated to the area of the former Warsaw Ghetto was started by the late Prof. Richard Freund from the Christopher Newport University and collaboration with the Warsaw Ghetto Museum began in 2019. In autumn 2020, Prof. Freund presented a plan for a joint project involving non-invasive archaeological research in selected locations of Warsaw. As the research was to be related to the history of Warsaw's Jews during World War II, it was obvious the interest would focus on the area of the former Ghetto, although, as we will see, not exclusively so.

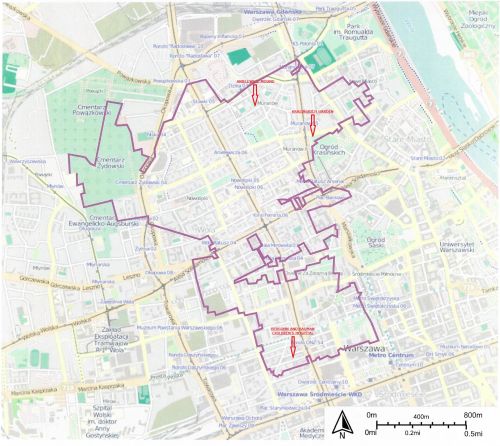

The selection of the locations for non-invasive research was made on the basis of the main criterion, which was the importance of a given location to the history of the Ghetto. As a result of the analysis and team discussion, four sites were finally chosen:

The sites were surveyed with different geophysical methods, including a magnetic gradiometer, electromagnetic terrain conductivity mapping using an EM38, metal detection with an EM61, soil resistance measurements using a twin probe resistance meter, ground penetrating radar (GPR), and electrical resistivity tomography (ERT). The primary aim of our research was to find out whether the selected locations contained tangible relics of the buildings from the period of the Ghetto's existence. We have to remember that after the war, Warsaw was not rebuilt exactly in its pre-war shape. The course of some streets changed significantly and in places, green areas replaced the densely built-up plots. When new buildings were erected on the ruins of the Ghetto, the debris had only partially been cleaned up, nor had anybody dug down into it. Therefore, our assumptions were that under the levelling layer of the rubble and the topsoil, there were still remnants of the cellars of the old buildings.

At all of the investigated sites, the relics of such cellars were confirmed. It was possible to locate clusters of metal and buried areas filled with loose rubble mixed with soil and to establish the probable course of the surviving walls (Konik 2021a). The state of preservation of the structures, as far as could be assessed on the basis of the non-invasive measurements, made undertaking the excavations reasonable.

A good example of the changes that took place in the formerly built-up area is the northern part of the Krasiński Garden. After the war, Świętojerska Street, which forms the boundary of the garden, was pushed to the north, and the garden itself was enlarged, taking over part of the former Ghetto area. It was the northern part of the Krasiński Garden that we selected first for non-invasive research and then for excavations. The site was within the Ghetto boundaries until the very end of the quarter's existence and it also witnessed intense fighting during the Ghetto Uprising. The as yet undiscovered third of the famous Ringelblum Archive was also hidden somewhere in the area (only two parts were recovered after the war).

We decided to carry out a short-term excavation in autumn 2021 to verify the potential spots of archaeological interest and to determine the nature of the strong anomalies detected using non-invasive methods, which indicated a large amount of metal accumulated in one place. The excavations uncovered the basement section of the wealthy tenement house, its status evidenced by the high-quality construction elements and by the objects of everyday use. The source of the 'metal' anomaly turned out to be a huge (over 12m long) construction steel beam, once part of the structural steel skeleton of the tenement house, which was at least three storeys high. We are not sure about its full height because documentation of the building did not survive.

From among the artefacts found on the site, our attention was drawn to a fragment of a Jewish prayer book (Prayer over the Torah) and to a small silver plate (measuring 2.5cm by 3.5cm) which used to be a Torah shield pendant (Konik 2021b). There are numerous analogies for such pendants in the form of small shields, with examples housed in the collection of the National Museum in Krakow and the Jewish Museum in Prague (Kuntoš 2012). The pendants were attached to the Torah shields with chains and often contained dedicatory inscriptions commemorating the living or the deceased. The inscription on the plate from Krasiński Garden proves it was dedicated to the memory of the late Nachum Morgenstern, who died in 1880. We managed to find the grave of Nachum Morgenstern in the Jewish cemetery in Warsaw, as well as those of his younger brother and their father. Some documents survived in the archives mentioning Nachum's marriage and the fact that he had two daughters. We were really happy that thanks to its discovery, we managed to restore the memory of this family.

In summer 2022, new excavations were undertaken in another location in the Ghetto area. As in the Krasiński Garden, the area was surveyed using non-invasive methods. This time we decided to examine the site in the immediate vicinity of the so-called Anielewicz bunker, where Mordechai Anielewicz, the commander of the 1943 Warsaw Ghetto Uprising fought his last battle and where he and his comrades died (they committed suicide while surrounded by the Nazis). Nothing certain is known about the bunker where they hid. According to the account of Cywia Lubetkin, who stayed inside the bunker for some time, it was a very large hiding place, stretching through the cellars under the three neighbouring tenement houses (Lubetkin 1999). At one time about 300 people were hiding there, and when the Nazis discovered the bunker, there were still about 120 people inside, which means the construction could not have been small.

During our research, we uncovered the remains of the cellars of the two tenement houses. Before the war they occupied the area between two parallel streets called Miła and Muranowska. Now this part of Muranowska no longer exists (it ran through the middle of today's grassy square). Because the buildings could be entered from two different sides, which was quite typical in pre-war Warsaw, they had double addresses: 18 Miła - 39 Muranowska, and 20 Miła - 41 Muranowska. The excavations were carried out on the side of the former course of Muranowska street because the part on the side of Miła Street is today occupied by the Anielewicz mound (the memorial monument to Mordechai Anielewicz and his companions) which obviously could not be disturbed.

In the exposed cellars, visible traces of the reconstruction activities were found that significantly changed their original layout. In the cellars of the 20 Miła - 41 Muranowska building, a room with concrete walls and remnants of a concrete ceiling was exposed, together with the electrical and water installations. At first the bunker had belonged to the wealthy smugglers who operated in the Ghetto and who later shared this hiding place with the Jewish Combat Organization fighters. Before the destruction of the building, the concrete room was clearly connected to the Anielewicz mound area through a network of cellar corridors that were also partially uncovered. This connection was additionally confirmed in a short excavation campaign in December 2022, where we explored the plot from the side of Miła St to the west of the Anielewicz mound.

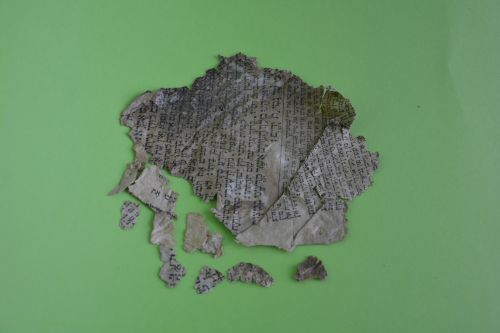

Another important discovery took place in the basement of the 18 Miła - 39 Muranowska building. In one of the rooms, we found fragments of plaster with painted decoration, and the remains of a burnt library of Hebrew religious texts (e.g. the Talmud). Some objects related to Jewish worship, such as tefillin, cups for ritual handwashing netilat yadayim, or the Torah pointer yad handle, were also discovered. It is highly probable that there was a house of prayer in this cellar.

We also found hundreds of artefacts of everyday use that create a picture of people's life in the place not only during the war but also long before (some objects can be dated to the 19th century) (Konik 2023). All the discoveries require further analyses but then they will form part of the future permanent exhibition of the Warsaw Ghetto Museum.

The excavations in the Ghetto area have also had a very strong social resonance. The research team met with the full understanding and support of the local community (Kajda et al. 2017). Elderly residents of the neighbourhood were eager to come and share their memories with the researchers. These meetings were very valuable both because we met witnesses of history and because they brought historically valuable documents. For example one gentleman, whose relatives died in the Ghetto, brought a set of the letters they wrote to his parents while in the Ghetto; the letters are currently being studied at the Warsaw Ghetto Museum.

An important social aspect of our activity was also cooperation with the volunteers who took an active part in the research. They included a large group of refugees from Ukraine and Russia, as well as emigrants from Belarus. It was significant and really moving for all of us that, for example, a woman from the bombed-out Ukrainian city of Kharkiv and an opposition journalist from Moscow were able to work side by side. They were united by their core opposition to the unimaginable crime of the Holocaust and regarded their participation in the archaeological research as a kind of tribute to the murdered Jews. The same empathy, sensitivity and understanding were evident regardless of the political differences. For all members of the research team, especially the youngest ones, it was a unique experience. It showed the great impact that can be made by the archaeology of recent times, not only in the scientific field.

The archaeology of the Warsaw Ghetto, like the archaeology of other places associated with the Holocaust, will remain a serious research challenge for a long time to come. Although the knowledge based on the analysis of available written sources is huge, archaeological research can complement it, revealing areas where written or iconographic sources do not provide sufficient data and identifying potential research fields. For obvious reasons, archaeologists who conduct excavations at any site related to the Holocaust, must also take into account a huge emotional burden and the fact that any activity will be perceived through the lens of the symbolism of that place. This imposes on the researchers special responsibility for each interpretation of the discoveries and the conclusions drawn, especially if the results of the research involve a deconstruction of the existing historical narrative and the construction of a new one.

Another profound challenge of such archaeological research lies in harnessing the potential of memories, for which the excavations are often a catalyst. In the course of the research, local individual microhistories are often revealed, which are worth not only documenting but also analysing if they have potential significance for the research team or local community. Another challenge is the public perception of activities such as excavating at a Holocaust site. The 'open door' policy in the excavation area, although somewhat troublesome in practice, seems to be the best solution in such a situation. Satisfying curiosity creates social approval and a favourable local climate for archaeological research. This is a very important element of the entire research process, even while going beyond its remit, because it is often related to the question of what will happen to the excavated site when the research is completed. In the case of the Warsaw Ghetto, this is an extremely important aspect, owing to its location in the centre of the large city. Here, the use of even small fragments of land evokes emotional reactions and conflicting interests (the convenience of the local residents, the necessity of commemoration expressed by memory guardians, and the needs of the entire urban organism represented by the city administration) often have to be reconciled. We hope that in the future, a special exhibition pavilion will be built in the area of the archaeological excavations near the Anielewicz Mound, which will perform both museum and educational functions. It will be a kind of memorial site, and for local residents, a space for meetings and reflection about the quarter in which they live.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.