Cite this as: Pramatarov, K. 2024 Archaeology of the Ottoman Period (15th-19th centuries) and Museum Management, Sofia, Bulgaria, Internet Archaeology 66. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.66.21

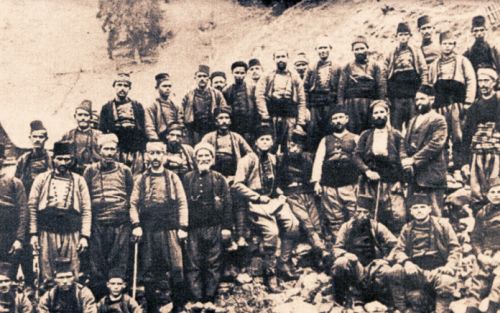

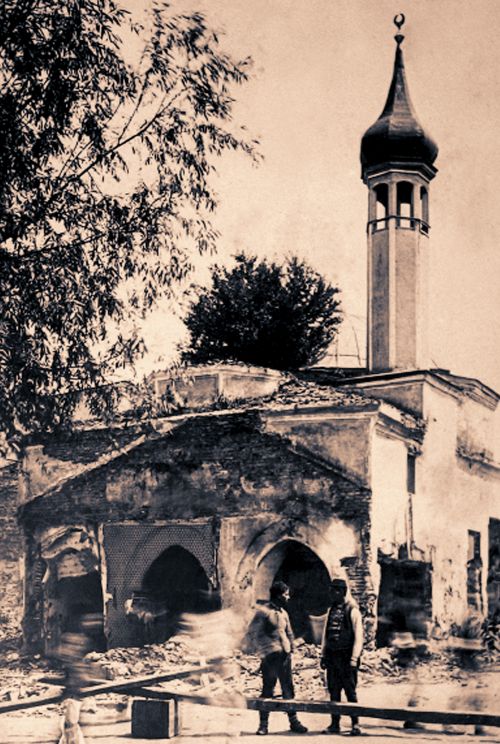

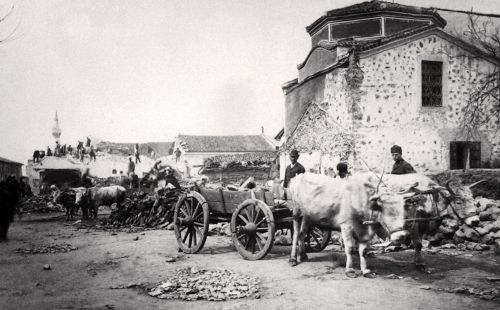

It is not an exaggeration to say that the prevailing view of the modern Bulgarian nation is to reject the Ottoman past and underestimate the scale of its archaeological record (architectural complexes and museum collections) (Strahilov and Karakusheva 2018, 179-80). Historical literature and school manuals tendentiously emphasised themes about the violence of the Ottoman armies and militarised brigands ('Κirdzhalis') against the Bulgarian population and the 'compulsory' imposition of Islam in place of the traditional orthodox Christianity (Figures 1-3).

During the so-called People's Republic of Bulgaria (9 September 1944 to 10 November 1989), the ruling communist party developed a specialised large-scale programme for the organisation of national and international museum exhibitions and founded the National History Museum, a cultural centre intended to retrace the complete historical development of Bulgarian lands. On 3 June 1976, pursuant to resolution no. 477, ratified by the Secretariat of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party, the Committee for Culture took the lead in a national mobilisation marking the 1300th anniversary of the Bulgarian state. This was a long-term programme (1976-2004) emphasising several main subjects: 'Bulgaria - a Land of Ancient Cultures', 'The Cultural-Historical Mission of the Bulgarian State', 'Bulgarian Medieval Art and Culture', 'Improving the Prestige of the Bulgarian State', and the 'Strengthening of the Role of Bulgarian Culture in the World Cultural-historical Process' (Недќов 2006).

Substantial resources were spent on the creation of scientific works and propaganda describing the Ottoman empire as an oppressor that had exterminated or expelled the elite of the Bulgarian nation and explaining the process of de-Ottomanisation by specifying typical forms of the Ottoman culture as 'revivalist' and 'national' (Трънќова et al. 2012, 9). Nevertheless, the last two decades have seen an obvious trend towards positive reconsideration of the Ottoman heritage in Bulgaria. The present article systematises the architectural and archaeological remains of the Ottoman presence and describes the modus operandi regarding their restoration and reconsideration within the context of the constant urban development of the Bulgarian capital - the city of Sofia. This article places on show the main trends and methods applied by the leading national museum institutions, the National Archaeological Institute with Museum at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (1892) and the National History Museum (1976), in the preservation, presentation, and socialisation of the remains from the Ottoman period (15th-19th centuries).

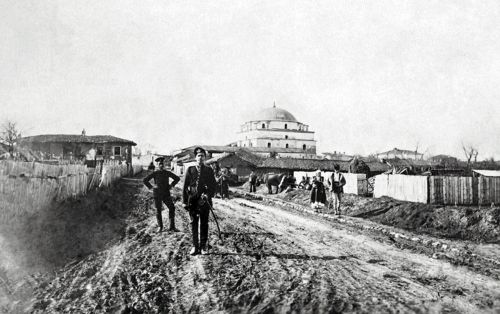

In the last quarter of the 19th century Sofia was largely rural in nature. The town had around 3000 houses, grouped in neighbourhoods (the so-called 'mahallah') and it had a population of some 15,000 inhabitants. The town was built with no plan. It was intersected in all directions by many narrow, mud-spattered streets, with religious buildings (mosques, churches, synagogues), schools, open markets, shopping arcades, baths, caravanserais, fountains and private houses (Станчева 2009) (Figure 4).

In the winter of 1878, the Russian army started an offensive against the Ottomans, and most of the Muslim population left the town. The arriving Russian soldiers destroyed dozens of Ottoman architectural monuments in order to provide themselves with building materials and firewood (Трънќова et al. 2012, 29-30). The purposeful destruction and reuse of Ottoman buildings became a policy of the newly established Bulgarian state, striving for the capital to be reorganised as a modern town based οn the European standard (Лори 2002, 10) (Figures 5-7).

Nowadays, Ottoman architectural remains in Sofia are scanty: three mosques, a prayer wall (namazgah), a warehouse near the so-called Military Club, and a bath (hamam) in Knyazhevo District, as well as two antique churches turned into mosques during the 16th century: the rotunda of St George and the basilica of St Sofia (Миќов 2012, 10).

The Buyuk Mosque ('The Big Mosque') was erected in the second half of the 15th century (1451-1494) by Mahmud Pasha, an administrator and vizir of the Fatih Sultan Mehmed (Карадимитрова 2005) (Figure 8).

It represents an imposing architectural complex built in 'cellular construction', with a square plan (36.30×36.30m) and inner space separated by four massive pillars on nine identical square spaces dominated by domes (Карадимитрова 2005). Near the main entrance, in front of the north-western wall of the mosque an arched vestibule covered by five domes was built which was destroyed by an earthquake in the first half of the 19th century (Миќов 2012, 13). The mosque used to be a part of a larger, no longer extant, religious complex including a school (mеdrese), a library, a caravanserai, and a well (sebil) (Миќов 2012, 14). During the Russian-Turkish war (1876-1878) the mosque was turned into a military hospital, and in 1879, the State handed it to the National Library with the Museum of Antiquities (the present Archaeological Museum) (Карадимитрова 2005).

The Black Mosque was built in 1547-1548 by the eminent Ottoman architect Sinan using Persian building traditions and wide application of antique spolia (Figure 9a-b).

It used to have a square plan (18.50×18.50m), and a dome (height: 22m, diameter: 18m). It was erected as part of an architectural complex which has been completely destroyed that comprises a public kitchen (imaret), school, hospital, bath, caravanserai, and library (Миќов 2012). In 1901, the mosque was redesigned as an Orthodox church ('The Seven Apostles') in accordance with the plans drawn up by the Bulgarian architects, Petko Momchilov and Yordan Milanov, under the supervision of the Russian architect Alexander Pomerantsev (Христодоров 1940).

The Banya Bashi Mosque is the only mosque still functioning in Sofia. It was built in the third quarter of the 16th century by Mola Efendi Kadu Seifullah (Миќов 2012) (Figure 10).

The building technique alternates rows of stones with rows of red bricks. The mosque has a square plan (15×15m), a central dome (diameter: 15m), a monumental arched three-domed foyer, and a minaret (Харбова 1985, 267). In the front façade, on both sides of the central entrance, two prayer niches (mihrabs) have been shaped. Around the religious building existed a bath, a water reservoir, a caravanserai, and the tomb of the notable Mola Efendi (Миќов 2012).

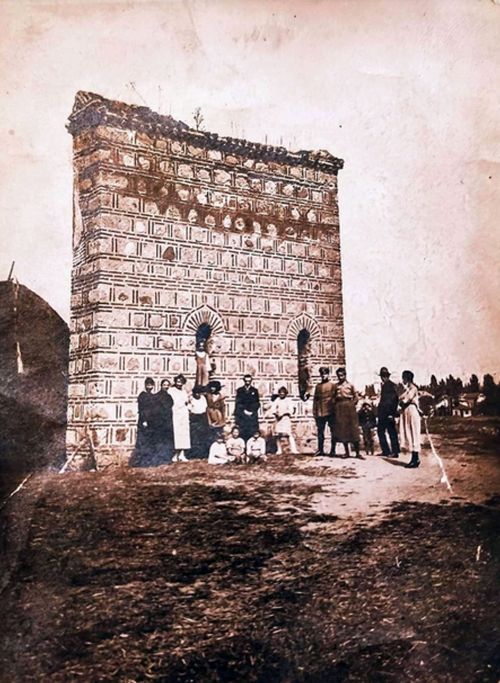

An intriguing example of Bulgarian rationalisation of the Ottoman cultural heritage is the case of the wall (height: 7.50m, length: 6.50m) with a niche for prayers (namazgah) (height: 4.50m, length: 1.80m) that was built in the 17th century in the outskirts of Sofia, on the territory of the modern market situated in Lozenets District (Figure 11). It was erected with bricks and plaster using 'cellular construction'. From at least the beginning of the 1940s, either through ignorance or unwillingness by Bulgarian citizens to remember, it was labelled as 'The Roman wall' and associated with the remains of the ancient city of Serdica.

In present-day Bulgarian museology, two indicative and entirely different approaches co-exist in the interpretation of the historical processes connected with the establishment of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans and the modern perception of Ottoman cultural heritage within Bulgarian society. At least two polarised viewpoints give various meanings and emotional connotations relating to the Ottomans.

The first is the result of the negative, traumatic rationalisation of the Ottoman Empire as a nomadic tyrant that in the course of five centuries had enslaved and suppressed religiously, socially, and institutionally the civilised and settled local Christian communities. This viewpoint is widely distributed in Bulgarian scientific and educational literature in which the Ottoman Empire is perceived as 'Islamic', and 'Turkish', and its influence on the Balkans can be encapsulated as the notion of 'oriental elements' that could be traced in the architecture, religion, clothing, food, and military science (Тодорова 2013). This belief has its roots in the period of the Bulgarian National Revival (1762-1878) when the Bulgarians started to build a self-identity by establishing a dividing line between their communities and the Ottoman Empire which was considered Islamic, multi-ethnic, deprived of social cohesion, and inhabited by multiple social and religious groups. This quite naturally lead to alienation and stigmatisation of the Old Regime as 'slavery', a radical interruption with and open negation of the past (Лори 2002, 7-9).

Nowadays, the 'nationalistic' approach toward the perception and rethinking of the Ottoman past is presented in the narratives of the Bulgarian history museums, whose permanent and temporary exhibitions give romantic, heart-breaking descriptions of the miseries inflicted on Christians by the Turkish infidels. It is common museum practice to keep material forms of the Ottoman spiritual and material culture in repositories and not exhibit them, as well as to illustrate the 15th-19th centuries with neo-byzantine orthodox art, and items related to Bulgarian monasteries, churches, language and literature, the struggle for national liberation, and the establishment and strengthening of the independent Bulgarian state (Figure 12).

The trend for typical forms of Ottoman culture (language, music, architecture, clothing, pottery, metal vessels, adornments, food, etc.) to be presented as products of Βulgarian traditions that had been developed and transformed by Ottoman and central European influences is also observable. Thus, from the pre-modern common Ottoman heritage emerges proto-national culture, considered intrinsic only to the Bulgarians and their territories.

An illustrative example of this trend is the National History Museum (NHM). It was established in Sofia in 1976 following a resolution ratified by the Bulgarian Communist party, describing its tasks as to introduce the history of the Bulgarian nation without allowing fragmentation of the undivided historical process, to present all aspects of our life in the past, to display the Bulgarian nation as creator and fighter for freedom and social progress, as well as to emphasise our contribution to the World Cultural Heritage (Недќов 2006). In the context of the large-scale and long-term cultural programme on the occasion of the 1300th anniversary of the Bulgarian state, a museum curatorial methodology was emphasised that focused on the Prehistoric cultures, the Thracians, Antiquity, Middle Ages, and the Third Tsardom of Bulgaria (1878-1946), subjects that still prevail in the permanent exhibitions of Bulgarian museums. In the case of NHM (last visited on 20 March 2023), the Ottoman heritage is sparsely represented: several rare golden coins of Ottoman sultans exhibited in the 'Numismatics' hall and two showcases in the central foyer of the museum that display subjects showing the flourishing trade and crafts during the Ottoman period (metal vessels, adornments, tools, trade scales, and weights) and the Ottoman conquest of the Balkans (armaments of a 'Turkish' officer and a Koran) respectively (Figure 13).

Βy turning the pages of the National History Museum tourist guide dedicated to the 15th-19th centuries, one could read:

'The Ottoman conquest had a tremendous impact on the states in Central and Western Europe. In Bulgaria, it destroyed the state and the church institutions and completely changed the social, economic, political, and cultural life of Bulgarians. The Ottoman Turks tried to enforce Islam on the defeated population and turn its doctrine into a dominating religion, thus ousting the established Christian traditions and achievements of culture. Islam was alien to the people and entirely different from their beliefs and practices… The Bulgarians were totally deprived of civil and political rights… Yet the mode of life, the Christian faith, and the memory of the past glory of the Bulgarian kingdom helped the people survive and oppose the foreign rule' (Марќов 2001, 3-4).

The second interpretation of the Ottoman cultural heritage within Bulgarian museology relies on a philosophical discourse for multiculturalism by focusing on the coexistence and the complicated symbiosis between the Turkish, Islamic, Byzantine, and Balkan traditions within the Ottoman Empire in the 15th-19th centuries. Thus, the Ottoman cultural heritage is thought of in its imperialistic frame, as a mosaic created by all the nations that had constituted it and were favoured by it. Without downplaying the segregation of Christians within the empire or the military crimes of Ottoman armies and penal brigades, this museological method rationalises as 'Ottoman' and 'positive' the continuity with Byzantine architecture, the development of trade and crafts, the religious tolerance, and the imposition of the Constantinople Patriarchy - the Orthodox Church of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans (Петрунова 2022, 16-17; Стайнова 1995, 33; Тодорова 2013).

In this regard, an indicative example is the National Archaeological Institute with Museum at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (NAIM-BAS), whose role is defined as the comprehensive study of the culture of tribes and peoples who have occupied present-day Bulgaria from the remote past until the 18th century. The museum is a real treasure-house of archaeological science and holds more than 500,000 artefacts. Detached from the structure of the National Library in 1895, since its very beginning it has been situated in one of the most representative Ottoman buildings in Sofia: the Buyuk Mosque (Figure 14).

The curatorial approach regarding the permanent exhibition focuses on co-existence and alternating Ottoman Muslim artefacts (tableware, religious vessels, a parade helmet) with Orthodox icons within the context of the overall context of the architectural monument (Figures 15-17).

The remains from the original interior of the mosque are remarkable: the partially preserved mural paintings with geometric and floral motives in two of the domes, and a two-leaved wooden door with religious inscriptions. Additionally, the depositories of the Archaeological Museum hold a considerable number of artefacts related to the Ottοman cultural heritage: offensive and defensive armaments, metal vessels, adornments, coins, stone monuments with votive, sepulchral, and construction character. In the representative depository are kept eight treasures dating from the 15th-18th centuries. In 2019, a temporary exhibition was organised entitled Late Medieval Treasures from the Depositories of NAIM-BAS, exhibiting the collective finds of precious objects found near the villages of Bohot, Bojenitsa, Glavanovtsi, Gorna Bela Rechka, Kostichovtsi, and Vasilovtsi in north-western Bulgaria and the maritime towns of Nessebar and Tsarevo (Василева 2019) (Figures 18-19).

Despite the controversial title containing the definition 'Late Medieval' instead of 'Ottoman' (which is a scientific quarrel with a long history in Bulgarian historiography), the example is important because the museum narrative emphasises the symbiosis between Ottoman and Balkan traditions in the context of the towns, where the inhabitants had demonstrated steadiness and adaptiveness toward the Ottoman model of civilisation (Василева 2019, 5). Between the 15th-19th centuries, the Ottoman town formed a centre of commodity-monetary relations, where the tradespeople and craftpeople (no matter if they were Muslim or not) had equal rights and belonged to a lower order of so-called 'citizens' (Ѓеоргиева 1997, 19-20). In the above-mentioned circumstances, an ethnically mixed social organisation emerged - the so-called craft guild (esnaf) that occupied an important place in the life of the Bulgarians by defending their economic and civil rights before the imperial administration (Василева 2019, 6). The townscape itself became 'the melting pot' between the Bulgarians and the Ottomans. In the field of artistic metalworking and jewellery-making, for example, even from the beginning of the 16th century clearly sensible changes in Bulgarian traditional medieval iconography were observable, marked by many 'stylistic contrasts, anachronisms, and strange synthesis, reflecting the phenomenon of multiculturalism in the context of the Ottoman empire' (Сотиров 2001, 170).

In conclusion, it could be said that 'nationalistic' and 'multicultural' interpretations of the Ottoman cultural heritage in Bulgarian museology are present, but not incompatible with each other. On the contrary, they could be moderated and combined successfully if substantial efforts were made to eliminate the existing, ossified prejudices and evaluations. This is an undoubtedly difficult but still possible and important task. Bulgarian museum specialists ought to minimise their political and emotional predispositions and aspire after a neutral professional method, giving an account of the indigenous cultural forms, cultural continuities, and mutual influences, thereby enriching the traditional 'old-fashioned' narrative.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.