Cite this as: Hale, A. 2024 Co-Archaeology: working towards the present through the complex nature of archaeology of the 18th to 20th centuries, Internet Archaeology 66. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.66.23

The title of this article begins with a suggested new term for our archaeological practices, one of collaboration and co-creation: Co-Archaeology. It aims to fulfil a terminology that encompasses the previous term of the Archaeology of the Contemporary (see below) but should, perhaps more pertinently, be known as 'Co-Archaeology', as a nod to recognising that archaeology can be co-created through collaborative, participatory partnerships.

This article contains a series of examples that it is hoped can enable European Archaeology Council members and readers to engage with a range of opportunities that 18th to 20th-century human interactions with each other, places and materials, have left for present and future people. The article will outline some of the more pertinent underlying theories and practices that have been developed, by reflecting on some of the available literature (call it a 'purview', rather than a systematic 'review'). From this it is hoped that readers will dive down into a variety of digital wormholes to explore practices, established themes and emerging trends that are available to help and inform our work when we focus on archaeologies of the 18th to 20th centuries. It is hoped that this article will enable readers to consider that all pasts are contemporary and can fruitfully be addressed from unfolding presents (Holtorf and Lindskog 2021, 12). These theories, methods and practices appear to resemble more of a hope-full, co-archaeological practice that can enable archaeologists to 'open people's minds and disrupt received perceptions of society, politics, places, peoples and material culture' (Bailey 2017, 695).

This brief literature purview aims to introduce the reader to some of the material available that considers archaeologies of the 18th to 20th centuries. Given this is a period of 300 years, this purview will in no way cover all sources; rather, it aims to focus on signposting readers towards certain themes which emerged from the papers given at EAC 2023 in Bonn, Germany, in March 2023 (Figure 1).

A glance at the programme of the symposium indicates that the majority of contributions discussed work on conflict across Europe and predominantly focus on the 20th century. This unsurprising bias towards the two world wars reflects an overwhelming narrative of the recent past that is prevalent beyond archaeology. But archaeology plays a key role and brings unique approaches in recognising, engaging with, bearing material witness, and amplifying the complex and unfolding narratives from those periods (for examples of theoretical and practice-based approaches, see Laurent Olivier's book The Dark Abyss of Time (2015) and Thomas Kersting's recent publication, Lagerland (2022), respectively). However overwhelming the conflict narrative remains, and rightly so, given the complexities associated with and the uses and abuses of past events there are other narratives to be engaged with as well. I hope the following literature purview reflects a breadth of subjects and inspires readers to look wider and sometimes beyond archaeology to engage with the unfolding pasts 'in and of the present' (Harrison 2011, 141).

Literature purviews are not common, so this brief section will undoubtedly reflect some of the author's interests, but it aims to provide a number of routes for readers to follow if they so wish. The purview is divided into a chronological format to reflect an incomplete history of the growth of what is commonly referred to as Contemporary Archaeology (González-Ruibal 2014). Others have done a much better job at creating literature reviews of this interdisciplinary archaeology (Harrison 2011; Graves-Brown et al. 2013), so this won't attempt another, but it will consider three general themes: conflict studies, materialities and socio-cultural changes, although we must recognise that all three are intertwined.

Given the ongoing conflicts that Europe's landmass and people can attest to, conflict studies provide a suitable topic for archaeological attention. Every European country can lay claim to have been impacted by conflicts over the past 300 years. It is over this timespan that we should be considering the scales of conflict, whose materialities and memories are very much present today. The materiality of conflicts that took place 300 years ago are the foundations (literal and metaphorical) for a number of more recent and present events that are still inflicting pain and suffering on people in Europe and beyond. These long-term archaeological issues have been studied by many researchers over the past 70 years. For example, Gabriel Moshenska's chapter (2013, 351-63) on 'conflict' in the Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Contemporary World, provides an excellent introduction to the themes and trends of 20th-century conflict. Rodney Harrison and John Schofield (2013) addressed suitable examples from the perspectives of traditional archaeological scales (artefact, site, landscape) and discussed a range of practices that included conflict sites, such as peace camps associated with Cold War infrastructure (e.g. Faslane Peace Camp; Figure 2).

Without Victor Buchli and Gavin Lucas' book, Archaeologies of the Contemporary Past (2002), we wouldn't necessarily have considered the wider implications of one of the first archaeological excavations of a Lancaster bomber in France (Legendre 2001, 126-37). However, recent reflections on practices applied in that volume and elsewhere have illustrated how archaeologists (and others) need to recognise their own agency and positions within the complex nexus comprising researcher-manager-subject-observer-participant, and conduct their research into the recent and contemporary past, while still adhering to appropriate ethical guidelines (Soderland and Lilley 2015).

With the archaeologies of the recent past comes the expansion of types of evidence, data and materials. From the traditional buried remains, we can apply the ongoing range of excavation techniques, but with the advent of new media such as video towards the middle of the 20th century, we are presented with datasets that archaeologists are less familiar with but nevertheless can assemble evidence, cross-check narratives, and compare and contrast with the material remains they recover. This enables our approaches to adopt more interdisciplinary, creative and collaborative practices. An example of this is Vesa-Pekka Herva's paper (2014) that brings together archaeological material from the Second World War found in Finland with the concepts of the uncanny, spectrology and hauntology. These somewhat unfamiliar areas of research do, in fact, complement the investigation of material remains, as they bring together theory and practise with the aims of exploring what multiple meanings objects and places can elicit. Stein Farstadvoll's paper (2022, 82-103) which focuses on the barbed wire installed during the Second World War in Norway, exemplifies how archaeological research into a supposedly mundane artefact from a past conflict can serve as a material witness/object, which contrasts with the grand, historical narratives that we so often fall back on when thinking about past conflicts.

When we consider the very last couple of decades of our symposium's temporal span, between the 1970s to the 1990s, we are presented with a range of potential archaeological subjects, which require new approaches that can lead to insightful results and impacts. These may appear unsettling for some as they take us beyond what we expect to be the subject and practice of archaeology. For example, the influences of 'street' cultures, such as skateboarding, graffiti and music, begins to appear on a range of scales, forms and materialities, which have more recently become the focus of interdisciplinary research with significant implications for cultural heritage management.

A project that focused on skateboarding culture at the South Bank in London is one such case (Madgin et al. 2018). The South Bank is a modernist building complex, and included a space known as the 'Undercroft', which was built in the 1960s. The Undercroft became a very popular spot for skateboarding in the 1970s and more recently a number of potentially detrimental redevelopment plans were objected to by the skating community, amongst others. This sparked a project into heritage authenticity issues, where an urban space became repurposed by skateboarders. As a result of the objections, cultural heritage management approaches shifted to enable the recognition of recent practices that redefined authenticity as 'negotiated, performed and experienced', while remaining grounded in the material fabric of the place (Madgin et al. 2018). The project exemplified the need for co-archaeological practices, including recognising the locus of 'expertise' lying outside of the academy or professional participants, and rather situated within a community of practice, namely skateboarders (Borden 2019).

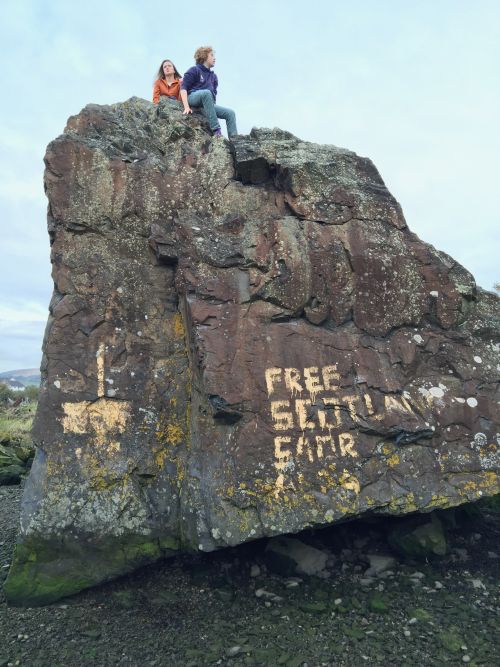

Other projects have similarly recognised the imperative to develop co-archaeology practices that involve archaeologists and cultural heritage managers, that enable participants to share their knowledge. In turn that form of co-creation benefits both their communities and the wider heritage sector. An example of this was the work undertaken by the ACCORD project at Dumbarton Rock, Scotland (Hale et al. 2017). In that case the experts were a community of climbers who shared their knowledge of their heritage with the project team. One of the outcomes was that the climbers contributed to the management statement for the designated, nationally significant monument of Dumbarton Castle (HES 2017) (Figure 3).

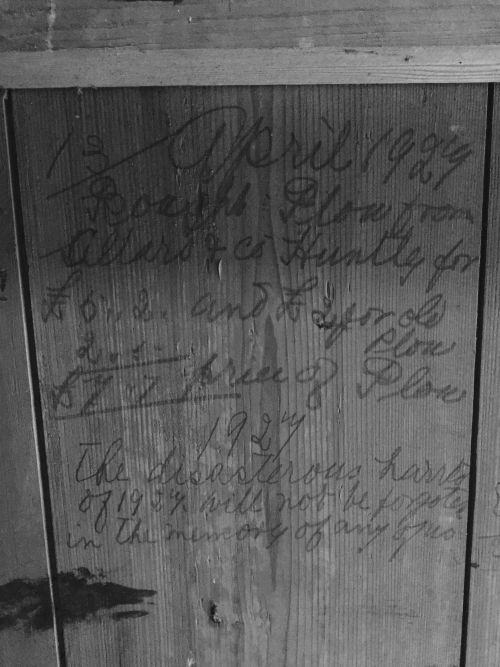

Following the theme of exploring, recognising and engaging with heritage beyond the traditional tropes, the graffiti on the walls of the Reichstag in Berlin provide a suitable historical precedent concerning preservation and indeed presentation, leading to more research, management and presentation of recent graffiti cultures (Foster et al. 2002). Archaeologists, amongst others, have begun to embrace recent graffiti as a subject worthy of research, as part of our broadening recognition of human engagement with places that take us beyond the traditional heritage tropes (Oliver and Neil 2010; Ross 2019). A recent project into 19th-century Scottish graffiti even helped cultural heritage managers at Historic Environment Scotland (HES) adjust the designation status to the highest level of a surviving rural mill building and its internal agricultural machinery, based on the pencil graffiti found written on the interior surfaces of the mill (HES 2016; Hale and Anderson 2019) (Figure 4). But without the creation of spray cans, which originated in the late 19th century, and the research by collectors, enthusiasts, and graffiti writers into the origins of mass-market material culture in the mid-20th century (Cap Matches Color 2015), archaeologies of this time period would be hope-less (Acker 2011; Hale 2023). These examples demonstrate some of the impacts that working on the margins of recognised archaeological subjects can produce and provide hope-full inspiration for future approaches, subjects and outcomes. But how do these projects and emerging approaches translate into the arenas of our contemporary lives, from mass-participation events to data profusion?

Even events of mass participation, such as the student protests across Europe between 1966-68, are now considered suitable subjects for archaeological investigation (Schweppe 2021). Projects that investigate these recent history events can also provide insights into how we practise archaeology of the very recent past and the present. For example, Carolyne White has been undertaking a co-archaeology project at the Burning Man festival in Black Rock desert, Nevada, USA for over 10 years (White 2020). Imagine the amount of archaeological evidence there is to be accessed from the numerous different types of European festivals that have taken place over the past 300 years?

But with more recent phenomena come challenges and opportunities as a result of data profusion, new data media and many more ways to create narratives about past events, issues and materialities. Two brief examples will suffice to highlight the complexities and opportunities that this era of archaeology can produce. The Teufelsberg in Berlin is a well-known site of conflict heritage, which comprises the beginnings of the Nazi-built Wehrtechnische Fakultät, part-built in 1937. This phase was followed by the dumping of rubble transported from bomb-damaged buildings in Berlin for over 25 years until 1971. It later became the site of Cold War infrastructure for British and US electronic data-gathering (Cocroft and Schofield 2020). The site now provides a range of spaces for creative responses (art/graffiti/performance). The Teufelsberg embodies a place in transition within our timeframe; from World War site to Cold War electronic data mining location to sub-culture, creative response, and is a work in progress. The contrasts could not be more stark, but the site illustrates the ways that spaces are being repurposed by and for new communities (Figure 5). One of the questions these spaces, structures, places and material remains present us with is: how do we suitably (archaeologically) engage with these mutable spaces and enable the communities that recognise them as their place and/or heritage, to participate in co-archaeology? Or should we recognise our limits and step back from intervening?

One response to these questions emerges from the late 1970s and early 1980s, when our cities began changing from industrial to post-industrial landscapes. At the same time, nightclubs were becoming a regular part of culture and they often occupied post-industrial buildings and spaces (museumofyouthculture.com). Space in city centres was at a premium and nightclubs were attempting to maintain a presence when rents were rising. Like all subcultures, community variations may not be recognisable by external observers, whereas within the culture those who self-identify will recognise one another. In Manchester in the 1970s there was a place where mixed race young people could spend time together, listen to music and share stories with friends: the Reno nightclub. In 2017, the site where the Reno once stood was going to be built upon. This precipitated a community project that included excavation, which recovered the material fabric of the basement nightclub, artefacts and resurrected the significance of this place in the history of mixed race young people in Manchester and north-west Britain. The importance of not only a community recognising its roots and tying those narratives to the material culture was evident from the responses from the community in Manchester and beyond, who responded, participated and became co-curators in the excavation and associated programme that aimed to uncover the histories of the Reno [PDF]. The impact of the work was transformational to many involved.

This brief introduction to co-archaeology recognises that the majority of 18th to 20th-century archaeology is focused on conflict remains, material culture and memories, but they are not the only narrative theme. This introduction attempts to provide additional avenues for further research, interpretation, and reflection. In doing so we come up against one of the enduring challenges in archaeology; one of both temporal and spatial scales (Edgeworth 2013). As our archaeological gaze ever widens to encompass the era of profusion, mass extinctions and new materialities, we are faced with decisions around value, significance and bearing witness to both the everyday and the extra-ordinary. So, perhaps this is where we not only acknowledge that the archaeological record will forever be subjective, flawed and imperfect, but embrace this messiness and the established practices that enable multiple participants to contribute to this incomplete record (Piccini and Schaepe 2014). It is perhaps this flawed nature of the archaeological record that makes it human; after all we are not complete (Jabès 1991).

We, as archaeologists and cultural heritage managers, are burdened with responsibilities to not only enable the material culture from sometimes deeply disturbing events to not only 'speak', but to behave in ways in which we may not have thought possible. This being the case, we have to be mindful of our work when it comes to the potential for it being misappropriated by people who want to use the past as narratives to justify pernicious actions in the present. This possibility reminds us that co-archaeology is political and we must resist complacency when it comes to how the past is constructed, curated and co-created. I also acknowledge that the period our symposium addressed is wrought with deeply emotive situations, ghosts and memories. For example, my grandmother left Berlin for Birmingham in 1939 to avoid persecution, and as a result was the only surviving member of her family (Klepper 1956, 765). She bought with her very little, but particular objects that remain in the family to this day remind us that material culture can be purposefully mediated through archaeological practices. Our approaches, methods and techniques can enable mute objects to become amplification systems for the distress suffered by millions of lives, across space and time. These lives, although past, can be recognised and remembered through our work (Figure 6).

There are three areas of work where we could consider investing a little of our limited resources, but boundless energies:

I would like to thank the EAC 2023 Scientific Committee for inviting me to give the closing contribution at the Bonn symposium, on which this article is loosely based. In addition, I'd like to express my gratitude and respect to the dedicated archaeologists, cultural heritage managers and curators who attended the symposium and undertake their work with passion, care and with an overwhelming sense of service to ensure that narratives about the past are told with sensitivity and integrity, in the present.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.