Cite this as: Johnson, T.D. 2024 Beyond Abandonment: Diachronically Mapping the Transformation of Domestic Sites in Rome and its Environs (1st–7th centuries CE), Internet Archaeology 67. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.67.15

The abandonment and reuse of Late Roman domestic buildings, as industrial sites, ecclesiastical foundations, necropolises, dumping grounds or improvised habitations, has been widely documented in all areas of the Empire. Scholars often frame these developments within the "end of the Roman house", a phenomenon thought to occur between the 5th and 6th centuries Common Era (CE) and signifying the replacement of classical domestic lifestyles and building types with more austere living conditions. Several studies have highlighted archaeological evidence seemingly in support of this narrative, but these have largely been limited to fragmentary and incomplete field data. Recently, however, increased appreciation for the topic of domestic abandonment in the Late Roman world has resulted in the wider availability of better, higher quality, stratigraphic evidence. In what follows, I present a new framework for analysing a subset of these data in the area of Rome, utilizing a tailor-made interactive map created in the game engine Unity. Focusing first on the background, rationale and design of this digital resource, I outline some of the trends it suggests regarding the long-term development of housing in Rome between the Early Imperial Era and Early Middle Ages (1st-7th centuries CE). These preliminary results confirm that Late Antiquity was a transformative period, but also raise the possibility that many of the activities normally associated with the end of the Roman house had earlier chronological (and thus social) origins.

In addition to offering valuable insights into the evolution of domestic practices around Rome, the interactive map underscores the benefits of utilizing Unity for digital visualization, cataloguing and data dissemination. Unlike the most common options for sharing geodata online (e.g. WebGIS), game engines offer enhanced capabilities in user interface design, allowing for customized outputs tailored to specific datasets. This flexibility facilitates not only the synthesis and communication of archaeological evidence but also the exploration of specific research questions and hypotheses. Given the experimental nature of this approach, an initial version of the interactive map is presented here to stimulate critical discussion and gather feedback, with the aim of refining future iterations and offering insights into the broader utilization of Unity for presenting archaeological data.

The approach I discuss in this article responds to the growing awareness that more critical methodologies are necessary for cataloguing and analysing the final phases of Roman houses (Dodd 2019; Sfameni 2020). In the wider field of Roman household archaeology, research since the 1990s has sought to move beyond a strictly structuralist framework for studying domestic space, drawing on toolsets rooted more firmly in archaeological theory and methods (Allison 1998, 2001; Ault and Nevett 1999; Nevett 2010; Dardenay and Laubry 2020; Baird and Pudsey 2022). As a result, specialists increasingly emphasize material over textual evidence, artefact assemblages over decoration and architecture, and analytical problem-solving over formal description.

Houses dating to Late Antiquity have occupied a relatively marginal position in this theoretical reappraisal. In central and northern Italy, for example, work in the last few decades has occurred largely independently of the debates unfolding in anglophone research about life "inside" Roman houses. Instead, researchers working in this area often focus on what Late Roman domestic sites tell us about regional social and economic transformations at the systems level, emphasizing a peak in the number of new domestic buildings between the 1st century before Common Era (BCE) and 2nd century CE, followed by a drop-off in new constructions during the 3rd century CE, and then an increase in new constructions in the 4th century CE, before the widespread abandonment of both urban and rural residences between the 5th and 6th centuries CE (Marzano 2005; Castrorao Barba 2012, 2020). When Late Antique houses are considered from a "dwelling perspective" (Ingold 1993), most scholars focus on their "aulic" aspects (Bowes 2010), represented most evocatively by the growing use of apsidal architecture in combination with lavish marble and opus sectile decoration (Guidobaldi 1986; Baldini 2001; Balmelle 2001; Romizzi 2003). Comparing these elements with the commentary of ancient writers like Olympiodorus, this new language of representation has been associated with a quintessentially Late Antique order of social relations, more draconian and lopsided than previous systems of patronage, in which private individuals sought to emulate the symbolism of palatial architecture (Thébert 1987; Sodini 1995; Arce 1997; Brenk 1996, 1999; Hansen 1997; Scott 1997, 2004; Tione 1999; Baldini 2001; Polci 2003; Sfameni 2004; c.f. Bowes 2010). Although this "hierarchization" paradigm (Bowes 2010, 32) is a rather clear example of the sort of traditionalist literary-based interpretive framework no longer favoured by Roman household specialists, it continues to characterize accounts of Late Antique houses in current research.

There is, however, another series of characteristics frequently encountered in Late Antique houses that match poorly with the sprawling, grandiose homes described by contemporary writers. In line with broader trends in Late Antique construction, building techniques can often appear haphazard and frequently utilize mixed, reused or perishable materials (Cagnana 1994; Parenti 1994; Brogiolo 1996a; Santangeli Valenzani 2000; Di Gennaro and Griesbach 2003; Lewit 2003; Chavarría 2004; Brogiolo and Chavarría 2008; Castrorao Barba 2012). Rooms are often divided by rough partition walls made with techniques like drystone, and the practise of "plugging" doorways, which involves walling up or tamponatura, is also commonly noted, thought to be suggestive of the disuse of entire spaces within a house (Ellis 1988; Di Gennaro and Griesbach 2003; Lewit 2005). In many cases, archaeologists have also recorded the insertion of burials in formerly residential areas and the transformation of residential spaces into utilitarian ones, including with the erection of post-built structures, sometimes directly to the detriment of existing decorative features (Percival 1976; Meneghini and Santangeli Valenzani 1993, 1995; Ripoll and Arce 2000; Balmelle 2001; Lewit 2003, 2005; Di Gennaro and Griesbach 2003; Chavarría 2004; Castrorao Barba 2014; Dodd 2019, 2021).

This evidence is most commonly interpreted as an indication of "downgrading," disuse or reuse, or a sign that the structure in question no longer functioned as a house (Ortalli 1992; Francovich and Hodges 2003; Chavarría 2004; Valenti 2007; Brogiolo 2011; Castrorao Barba 2014). In the context of the widespread abandonment of domestic sites starting in the 5th century CE, such phenomena have been primarily discussed in terms of the "end of the Roman house" (e.g. Brogiolo 1996b, 2006; Ripoll and Arce 2000; Baldini 2003; Brogiolo et al. 2005; Brogiolo and Chavarría 2008; Chirico 2009; Machado 2012; Castrorao Barba 2012, 2020; Cavalieri and Sacchi 2020; Cavalieri and Sfameni 2022), or the idea that the "poor" building forms of Late Antiquity resulted from "the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a few aristocrats" (Ellis 1988, 573), producing a compounding effect on existing social and economic crises.

While some have criticized this crisis-driven view (e.g. Lewit 2003, 2005, 2006; Munro 2010, 2011, 2012), attempts to offer more neutral explanations for the apparently widespread change in lifestyles by the 5th-6th centuries CE have been met with scepticism or rejected outright (Volpe 2005; Brogiolo and Chavarría 2014; Sfameni 2020). Other criticisms of current approaches have centred more squarely around methodological issues, in particular the lack of a standardized framework for tracking change in domestic spaces at multiple diachronic scales. This has led to "little or no attention paid to the trajectories of individual sites" (Dodd 2019, 30), a problem exacerbated by the historically scanty state of documentation for most of the relevant evidence.

Today, evidence for the transformation and abandonment of Roman homes is markedly increasing in scale and complexity, producing a need to re-evaluate methods for diachronically evaluating domestic use (i.e. the continuity of activities normally associated with a "classic" Roman house) and disuse (i.e. activities pointing to downgrading or abandonment), the essential concepts underpinning current understandings of the end of the Roman house. The city and surroundings of Rome, although not usually considered a useful laboratory for household archaeology (Hales 2003, 11; De Franceschini 2005, xiii), has now emerged as a productive area for exploring new approaches. Beyond its obvious historical centrality, Rome offers a uniquely large range of evidence for ancient housing in terms of social scale (from small rustic abodes to expansive urban domus), physical context (from the city centre to the suburb to the distant hinterland), and chronological breadth (from the Late Republic to the Early Middle Ages). During the last two decades, the depth of this evidence has increased significantly on the back of modern Rome's urban expansion (Egidi et al. 2011), occurring in tandem with the development of new tools for disseminating archaeological data, such as the Sistema informativo territoriale archeologico di Roma (SITAR) (Serlorenzi et al. 2021). These factors make the city an ideal candidate for an updated assessment as well as a reconsideration of the best methodological practices for incorporating a vast range of stratigraphic data for domestic sites covering a multi-century range.

Although standard approaches to the Roman house leave little room for the analysis of diachronic transformation in single sites, change must be a fundamental element in any account of ancient residential buildings, especially when it comes to their abandonment. A greater focus on the integration of stratigraphic evidence into site narratives is one way of providing a more dynamic account. Unlike considerations limited to the study of formal architectural qualities, which can produce the erroneous impression that houses were static "built spaces", stratigraphic interpretation inspires consideration of human activities, casting more attention on individual site trajectories. Moreover, while architectural interventions in Roman houses were obviously significant affairs and should be recognized as such, many cases examined in this study show how the physical modification of buildings was not always limited to major remodelling projects but could unfold in a piecemeal fashion alongside (or even as a result of) the occurrence of mundane domestic activities. It is therefore important to acknowledge how daily life might evolve at a faster pace than the physical structures of built space. While the division of a building's life course into discrete phases continues to be an essential element of archaeological reasoning, stratigraphic data can help fill in the gaps left by approaches centred almost solely around key moments of architectural change.

Stratigraphic data nevertheless have their limitations in a household context. Short-term adaptations to taste, environment, economic events, social trends and everyday occurrences can be challenging to observe archaeologically, owing to the unique formation processes of stratigraphy in domestic sites (Foxhall 2000). The sweeping of floors, the disposal of unwanted objects, the clearing of waste and the use of perishable furnishings, are just a few examples of regular domestic activities that could have prevented evidence of daily life from entering into the stratigraphic sequence (LaMotta and Schiffer 1999; Furlan 2017). It is essential to remain cognizant of these issues, asking questions appropriate to the nature of the available evidence (Allison 2022).

With these issues in mind, the starting point of my analysis was the development of a catalogue of 16 activities across 46 domestic sites in and around Rome from the 1st to the 7th centuries CE. To varying degrees, each of these activities has been a factor in previous discussions of domestic continuity (the reiteration of familiar Roman housing types and practices) versus discontinuity (downgrading and the end of the Roman house). In order to highlight and explore the fault lines of this contrast, I grouped the 16 activities into two thematic categories, indicators of use and of disuse (Table 1 and Table 2).

This choice must be carefully highlighted as a thought experiment for evaluating previous assumptions, not an a priori interpretation of the data. My aim here is twofold. The first is to delineate in explicit terms a series of archaeological markers that, with some exceptions (e.g. Chavarría 2004), have mostly been left to implicit definition, even as they have been central to debates about domestic transformation in Late Antiquity. Second, I wish to explore the extent to which trajectories of perceived "use" and "disuse" in Roman houses indeed reflect current narratives regarding the evolution of domestic sites throughout the Imperial period, culminating with the end of the Roman house.

| Domestic use activities | |

|---|---|

| Activity | Evidence |

| Decorative interventions | The creation or maintenance of decorative pavements, wall or ceiling frescoes, decorative architectural elements (cornices, colonnades, apses, etc.), aquatic features, or other elements contributing to the symbolic embellishment of the household |

| Utilitarian interventions | The creation or maintenance of roofs, hydraulic infrastructure, non-decorative floor surfaces, or other elements essential to the functioning of the home but not strictly related to symbolic representation |

| Regular masonry construction | Masonry structures in standard Roman techniques |

| Storage, preparation, consumption of food | Ceramic wares for storing, cooking, or eating; installation/use of hearths, ovens, or pits for dolia; collection of storage/transport vessels in specific areas; organic food waste |

| Agricultural/industrial production (in purpose-built areas) | The construction, maintenance or use of agricultural or industrial production facilities distinct from residential areas of the house |

| Funerary (extra-household) | The construction of tombs, monumental or otherwise, in designated areas with immediate proximity to, but not inside, the residence |

| Domestic disuse activities | |

|---|---|

| Activity | Evidence |

| Closure of spaces | Construction of tamponatura or walls built to fill in a doorway in order to block or restrict access to a space, regardless of building technique |

| Subdivision of spaces | Construction of partition walls in rooms or courtyards, regardless of building technique |

| Destruction of decorative elements | Cuts, new floors or other modifications that destroy, interrupt or cover previous decorative elements |

| Irregular construction | Masonry, floors or other structural elements in irregular techniques, including drystone construction, the laying of irregular courses, or the utilization of irregular or second-hand materials |

| Post-built/perishable building | Postholes or other evidence for perishable timber structures |

| Christian worship | Christian cultic structures within the space of the residence |

| Spoliation | Negative features (cuts or spoliation trenches) related to the removal of reusable materials. The collection of bricks, roof tiles, glass, marble fragments or other reusable materials into stacks or piles, presumably for transportation elsewhere or recycling back into raw form |

| Dumping | The deposition of waste, refuse or soil inside or around the residence |

| Agricultural/industrial production (in readapted areas) | The construction, maintenance or use of agricultural or industrial production facilities in formerly residential areas of the house. |

| Funerary (intra-household) | Tombs inside the residence or abutting the outside of its perimeter walls. These include various typologies: a cappuccina (reutilizing second-hand roof tiles), a cassone (rectangular trenches lined with stone-built perimeters), infant enchytrismos burials using amphorae, and simple inhumation trenches are the most common |

The 46 case studies, ranging from elite residences to smaller dwellings in the city and suburbs, provide a cross-sectional representation of Rome's diverse record of ancient houses. Drawing upon resources such as the SITAR platform (Serlorenzi et al. 2021) and the databases of the University of Siena's LIAAM (Laboratorio di informatica applicata all'archeologia medieval; Valenti 2014) and University of Padova's Tess (Sistema per la catalogazione informatizzata dei pavimenti antichi; Angelelli and Tortorella 2016), I first identified around 250 potential case studies. Initial exclusion criteria included a lack of stratigraphic excavation techniques or the absence of documentation for final phases and this resulted in more than 100 sites being excluded.

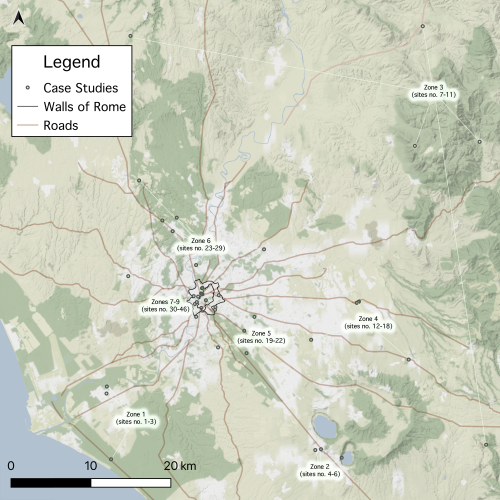

Geographical considerations also influenced site selection, with a 40-km radius around the Forum Romanum serving as a distance-based criterion. This decision, while somewhat arbitrary, roughly corresponds with the suggested limits of Rome's regional footprint in current research (Cifarelli and Zaccagnini 2001; Goodman 2007; Mandich 2015). My study organizes the 46 sites within this radius into nine microregional zones (Figure 1), aiming to offer a comprehensive view of Rome's interconnected and varied suburban landscape. This acknowledges Rome's nature as an extended metropolis operating at a regional scale in cultural, demographic, political and economic terms (Witcher 2005; Dubbini 2015).

An important note regards the absence of sites from within Ostia in this study. While villas from around Ostia were included, the suburban centre's unique microhistory and immense excavation record require a standalone effort beyond the scope of my current work. As new data and analysis for Imperial and Late Antique Ostia continue to emerge (e.g. Gering 2014; Massimiliano et al. 2014; Boin 2013; Batty 2018; Poulsen 2020a; Ellis et al. 2023), future iterations of my research will aim to integrate this essential evidence.

The decision to structure my study around century-by-century accounts of each site is an intentional strategy reacting to the nature of the available evidence and the research questions described above. Tracking the 16 activities by century rather than focusing on the phases of each building as defined by their excavators offers a flexible way of synthesizing and analysing diachronic change. In addition to providing a more complete view of each site's life course "in between" phases, a standardized chronological approach also addresses the fact that occupation or construction phases tend not to be reported consistently in field reports, and sometimes not at all.

In some cases, the evidence for specific activities provides a more precise chronology than reported in the catalogue. For the majority of instances, however, the best-case scenario is a possible chronology within a 100-year range, with many examples encompassing multiple centuries. Therefore, in the interest of consistency, all activities are tracked by single century, an acceptable level of precision given the limitations of assessing absolute chronologies for many stratigraphic contexts.

The data catalogue behind the interactive map (see Data files) is distributed over two parallel long-data structure tables, meaning that the activities associated with single sites occur over multiple rows. There are nine total rows of data for each site (one for each century from the 1st century CE-7th century CE, one for undatable evidence, and one for post-7th-century CE evidence), and each column records possible instances of the 16 given activities within the specified time frame. For the 46 sites in my catalogue, this results in 414 lines of data per table.

Apart from their identical structure, the two tables differ in the data types they handle. The first records nominal data: written descriptions of each recorded activity per century, with citations and a total date range. The second records ordinal data: a numerical ranking, 0 to 2, describing the chronological reliability of each activity type per site, per century. "0" represents the absence of any detected activity. "1" represents the appearance of at least one activity instance potentially datable to the century, but no securely datable instances. "2" indicates the presence of at least one activity instance securely datable to the century, regardless of whether other less securely datable instances also occur.

The composition of each activity list in the nominal table was subject to a series of judgements. For example, the sequential ordering of activities for each century is necessarily arbitrary but consistent, first providing any securely datable activity instances before listing those whose possible chronologies encompass a multi-century range. Groups of very similar activities might appear as a single entry to avoid repetition. Alternatively, single activities might sometimes satisfy more than one of the 16 categories. For example, a single tamponatura built with mixed second-hand materials could be classified as two activities: closure of spaces and irregular construction.

In instances when activities could not be dated beyond a terminus post quem (or, more rarely, a terminus ante quem), the catalogue attempts to reflect this uncertainty. For example, if a terminus post quem of the 3rd century is reported, this activity would receive a low ranking ("1") in terms of chronological reliability for the 3rd century. Depending on the specific circumstances (e.g. stylistic elements or a reliable terminus ante quem), the decision might be made to extend the possible occurrence of this activity up to subsequent centuries as well. Conversely, activities dated solely on the basis of relative chronology are sometimes classified as undatable if no reasonably secure terminus post quem or terminus ante quem is available.

The catalogue published with this article represents a snapshot of my ongoing research, which is subject to future revision and expansion. To the degree that much of the data reported here pertains to sites undergoing continued excavation or analysis, my findings and organization of the data should be considered preliminary. Therefore, while the catalogue is intended to provide an up-to-date account of the evidence around Rome, my aim is that it will evolve as more detailed evidence emerges and new discoveries are made.

The approach described offers a robust solution for compiling this research, but not for intuitively visualizing its results. Normally, catalogues are reproduced as printed charts or lists, formats with a limited ability to reveal essential patterns and communicate critical interpretations. Maps, meanwhile, are the obvious choice for representing large collections of archaeological data in a regional context, yet traditional maps produced in a geographical information system (GIS) environment are subject to deeply rooted cartographic conventions, meaning the solutions they offer for creative approaches to unique datasets are limited (Eve 2012; Fredrick and Vennarucci 2021; Frey 2023). As still images, maps are also poorly suited to representing diachronic change, a key emphasis of this research.

These problems all factored into my choice to design a purpose-built interactive map with the game engine Unity for analysing and presenting my catalogue. The design of this interface is intended to intuitively convey findings at an interpretive level. In order to achieve this, I first generated the data tables described above along with a series of base raster map tiles using QGIS. Next, I created a C# script enabling Unity to read the tables as .csv exports. Then, the raster maps were exported and tiled together as the basis of a 2D Unity scene.

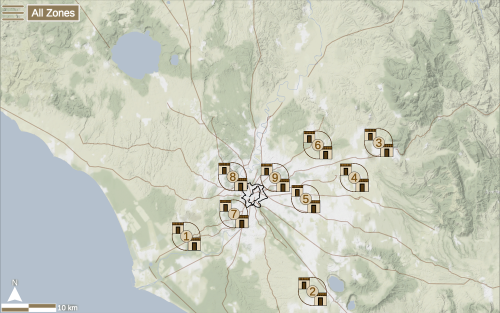

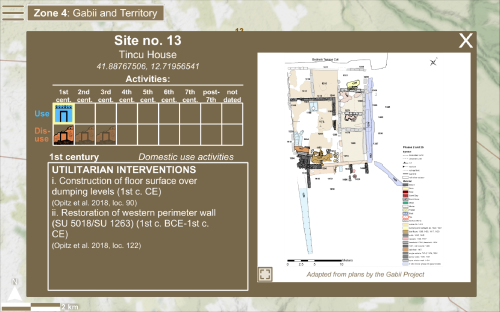

The main novelty of the map is its tailor-made graphical user interface and interactive functions for exploring the data. Upon first opening the map, viewers are presented with a regional overview of the study area, with icons representing each of the nine topographical zones discussed above (Figure 2). Clicking any of these icons navigates to a more detailed view of the zone and its individual sites (Figure 3). Then, the icons appearing for individual sites in each zone's map, when clicked, open a window containing a colour-coded and symbolized chart, summarizing the house's catalogued data (Figure 4). The top row of this chart represents evidence for domestic use activities, while the bottom row indicates domestic disuse activities. Each column stands for one century, and the colour of each cell indicates the highest level of chronological reliability among all the activities recorded in the given timeframe. If no activities are recorded for the given century, the cell is blank. If at least one activity possibly dated to the century is recorded, but none that is securely datable, the cell features a transparent icon. Finally, if at least one activity is securely dated to the given century, the cell features an opaque icon. Clicking on an individual cell displays the extended descriptive data associated with that century in list form, along with the relevant citations. The chart thus provides an instant graphic summary of the research results.

The window opened by clicking on the site icons provides some further information useful for contextualizing the reported data. In the top left, beneath the number and name of the site, the location of the site is listed in decimal degrees following the WGS84 format, the standard coordinate system used by Google and other web mapping services; these coordinates can be selected and copied to the user's clipboard by pressing control/command + c. To the right, a plan of the building is provided. Site plans have been sourced directly from excavation reports and other publications but have been cropped and modified to match the chosen dimensions of the Unity interface. Wherever possible, labels have been added to clarify the location of room numbers or areas of the house mentioned in the catalogue. The button in the bottom left of the plan allows users to enlarge the image within the Unity frame.

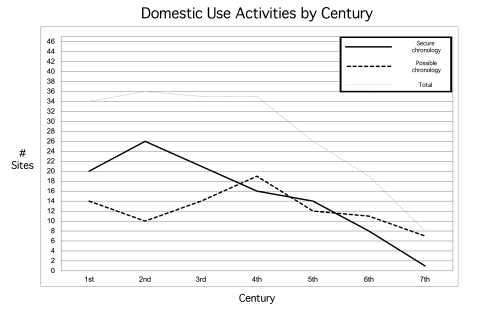

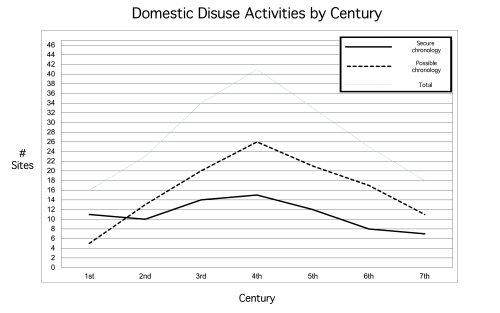

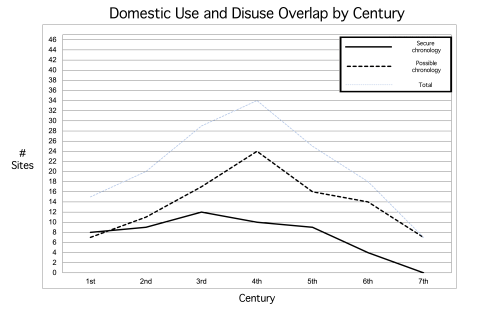

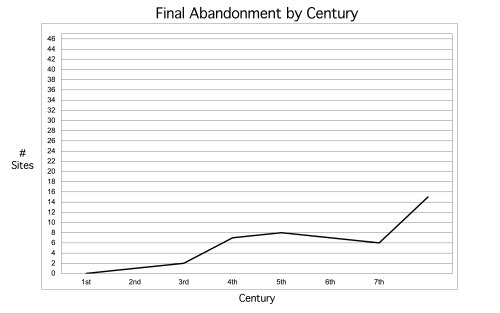

The century-by-century accounts in the interactive map cast focus not just on single sites, but broader regional trends. In order to illustrate this, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 display, respectively, the total number of sites with use activities, disuse activities, and both use and disuse activities, by century. Figure 5 and Figure 6 specify the number of instances with a secure chronology for the use and disuse activity groups, respectively (i.e. with at least one "2" in the ordinal data table for the activity group in question), possible chronology (i.e. with at least one "1" in the relevant activity group, but no "2"), and then the total number for these two sets of values summed. Figure 7 shows the number of sites where use and disuse activities overlap, accounting for secure and possible chronologies in the same way. Meanwhile, the number of sites by century with an overall cessation of activities, whether use or disuse, is reported in Figure 8.

Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 8 confirm that, in the area of Rome, there was an uptick in domestic disuse activities and a tapering off of traditional use activities leading into Late Antiquity, accompanied by an overall downturn in the total number of occupied sites. However, Figure 7 reveals how apparent use and disuse activities could frequently overlap in single sites. Often, depending on which specific areas of a house are considered, different impressions could be drawn of its overall trajectory in a given moment. For example, during the 1st century CE, site no. 1 (Zone 1) was the subject of extensive remodelling, with a focus on monumental and decorative elements like mosaics, fountains and colonnades (Ramieri 2008; Buonaguro et al. 2012; Marcelli 2019; Db Carta Archeologica LIAAM, Site ID 0580910144). Simultaneously, Room B (labelled on the plan as atrio), likely the entrance of the villa in an earlier phase, had its original doorway walled up and was subdivided into two spaces. A new pavement was then installed, consisting of heterogenous reused materials. The counter-like feature built in this room, the materials recovered within it, and the presence of nearby dumping layers containing food waste, suggest that these changes might have been related to its conversion into a kitchen. In sum, Room B is a good example of how an apparent case of downgrading in a space positioned within the decorative area of a house could relate to ongoing daily domestic use activities, not the overall disuse of the building.

While this is a rather obvious example, there is rarely a clear cut-off between a building's primary period of occupation and its overall disuse. Consider, for example, site no. 7 (Zone 3), where, sometime between the 3rd and 5th centuries, a series of rooms was constructed in the villa's southern corner at a diagonal angle with earlier walls (Brouillard and Gadeyne 2003, 2006, 2011, 2012, 2013; Brouillard et al. 2012). Contemporaneously, some sections of the villa experienced collapse or were used to heap trash, even as contextual evidence like butchered animal bones, tableware and storage jars shows that it continued to be a lived-in space. Therefore, the cattycorner walls may have been a physical interruption of the earlier layout, and this should be understood as a moment of significant change at the site, but they were not an interruption of the building's essential domestic function and might have served to make it a more liveable space.

Even during periods of apparent prosperity and "upgrading," use and disuse often emerge as tightly entwined phenomena unfolding rhythmically throughout the occupational history of a building. A good example of this is site no. 40 (Zone 8), located in the centre of Rome, which fluctuated between phases of spoliation or voluntary destruction and phases of building or remodelling (Faedda 2019). Similar oscillations can be observed at site no. 33 (Zone 8) (Acampora 2017; Saviane 2017), and to varying extents are reflected in most of the sites examined in this study that incorporate ostentatious or monumental elements. This serves as a reminder that the destruction, dismantling and reuse of preexisting building materials and spaces was a regular aspect of Roman housebuilding. Such practices were not necessarily limited to Late Antiquity, casting doubt on the notion that architectural recycling was always a phenomenon born out of strict necessity or a lack of resources at the systems level.

A further aspect of the dataset that illustrates this point is the preponderance of "early" (i.e. pre-Late Antique) instances of disuse. Two notable examples are located in the settlement of Gabii (Zone 4), a suburban centre famous for its proverbial decline and abandonment during the Imperial Era (Becker et al. 2009). Consistent with this image, site no. 13, located near the settlement's main thoroughfare, shows a complete cessation of domestic activities by the 1st century CE. Around this time, it was converted into a necropolis, a phenomenon typically associated with suburban sites only from the 3rd century onwards. Nearby at Gabii, tombs were also documented inside site no. 16, in this case dating to the 3rd-4th centuries, more in line with known regional trends. However, unlike site no. 13, site no. 16 showed ongoing signs of domestic occupation after the 1st century CE and as late as the 3rd century (including the deposition of food waste and small-scale structural interventions), even as it exhibited some of the more typical signs of disuse frequently encountered in later periods (e.g. the subdivision of rooms, the construction of tamponatura blocking doorways, and the spoliation of architectural elements such as the basin of the impluvium).

Site nos 13 and 16, along with their neighbours, site no. 12 and site no. 14, show that domestic life could exist in a seemingly downgraded state prior to Late Antiquity. The transformation of these buildings should obviously be considered within recent evidence for Gabii's overall contraction and reorganization during the Imperial period (Samuels et al. 2021a, 2021b). In particular, the appearance of graves in the city centre of Gabii is a clear example of intramural burial, and, while this is normally considered a violation of Roman legal and religious norms, tombs were a regular element of suburban landscapes (Emmerson 2020). This perhaps suggests that Gabii was undergoing a process of "suburbanization" during the Imperial period, with key effects on the occupation of its domestic buildings (Samuels et al. 2021a), underscoring the importance of a context-driven interpretation of domestic transformations. On the other hand, there are also strong indicators of Gabii's urban continuity following the 1st century CE, including public building projects and imperial investment (Samuels et al. 2021a), not to mention evident periods of prosperity in domestic buildings both within the settlement (e.g. site no. 15) and in its immediate surroundings (e.g. site no. 18). As a result, the apparent downgrading of Gabine homes cannot simply be chalked up to an early case of crisis or desperation prefiguring Late Antiquity, and this undermines the teleological undertones of the "end of the Roman house" narrative. Instead, the houses of Gabii are evidence that at least some aspects of the domestic transformations normally considered a unique product of Late Antique decline were in fact tied to practices with earlier roots.

While these findings are still preliminary, they invite a re-evaluation of some common assumptions about Roman houses. Symmetrical and carefully planned layouts, the decoration of public-facing areas like the atrium and adjacent rooms, the separation of decorative spaces from utilitarian facilities, and the use of purpose-made building materials, were indeed important aspects of Roman residential buildings. Yet these characteristics must be recognized as only part of what made a Roman house "Roman". Improvisation, the adaptation of pre-existing spaces for new purposes, the use of second-hand building materials, the dumping of waste in sometimes unexpected areas, and the prioritization of functionality over monumentality, were all additional, frequent, aspects of residential buildings in Rome throughout the Imperial period, not just during their abandonment or downgrading in Late Antiquity. These qualities remind us that Roman houses were negotiable spaces and that the conditions of daily life in the ancient world might not always have aligned with our current expectations. For the Late Antique Roman house, if we limit our focus to apsidal halls, elaborate marble panelling and opus sectile pavements, we miss this negotiable aspect, confusing monumentality for continuity, and natural trajectories of transformation for discontinuity or even abandonment.

Methodologically, the affordances for analysis and communication of the interactive map behind this study demonstrate the benefits of using game engines like Unity to visualize and represent archaeological data relating to household excavations. While the version presented here represents a first attempt, the next iterations will take fuller advantage of Unity's capabilities. In particular, future tools envisioned include the development of interactive, more extensively annotated, plans enabling the visualization of activity distributions across specific building spaces, the integration of 3D data to enhance focus on vertical/stratigraphic factors (and thus change over time), and additional functionalities for searching, filtering and comparing data.

While these future developments are sure to provide richer insight, the work presented here confirms the growing sense that there is a need to rethink abandonment in domestic contexts by more clearly defining the criteria for identifying related activities and their overall implications. Waste disposal, for example, is one area where recent research has demonstrated the benefits of a more critical approach to identification and analysis (Emmerson 2020), including for domestic sites (Furlan 2017). This, alongside ongoing consideration of the possible link between intramural and intra-household burial, and the increasing realization that irregular construction techniques were a fundamental aspect of the cultural milieu in all periods of Roman history, will be essential factors to consider moving forward. Along with a deeper exploration of microregional and environmental trends within the dataset, future research will also expand upon the significance of socioeconomic factors in determining household trajectories. Among many sites in this study, there is an inverse correlation between the ostentation of a home and its propensity for dynamic change within short periods of time (e.g. site nos 7, 31, 34, 35, 36, including before Late Antiquity. This raises the possibility that some seeming instances of "disuse" can be more meaningfully contextualized within the domestic practices of sub-elites, a topic that is only now beginning to receive significant attention (Bowes 2021). The results highlighted here suggest that, at least for the city of Rome itself, what has normally been called "the end of the Roman house" was a phenomenon that started earlier, lasted longer, and followed a more varied course, than previously recognized.

The interactive map published with this article is a WebGL application designed in Unity. WebGL, a JavaScript API, provides a stable format for hosting 3-dimensional (3D) graphical applications on the web. To ensure the long-term preservation of the data presented in the map, the original tables underlying the map's interactive components have also been provided in .csv format. All data sources, including for figures, are cited in this article and the accompanying Unity interface. Permission is required from the authors and/or copyright holders of all data for reproduction. Map tiles in the Unity interface and screenshots in this article are adapted from tiles provided by Stamen Design, under CC BY 4.0 (data by OpenStreetMap, under Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODbL)). Geodata for Roman roads and walls depicted in the Unity interface and screenshots in this article are from the Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire, under CC BY-SA 3.0. Data from the database of the Laboratorio di informatica applicata all'archeologia medieval are cited by providing the site ID (e.g. Db Carta Archeologica LIAAM, Site ID 0580580002). Special thanks to Dr Marco Valenti and Dr Vittorio Fronza for providing access to this data source. Data from the Sistema informativo territoriale archeologico di Roma are sourced from the Archeositarproject platform (thanks to the Soprintendenza Speciale Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio di Roma) and are cited by providing the OI (Origin of Information) number (e.g. SITAR OI code 11858). Special thanks to Dr Mirella Serlorenzi (director of the SITAR Project) and Dr Stefania Picciola. Special thanks also to Alessio De Cristofaro, Fabrizio Santi and Diletta Menghinello, archaeological officers of Municipi I, XI, XIII; II, IV; and I, VIII, respectively. Finally, thanks to Nicola Terrenato, Lisa Nevett, Elaine Gazda, Paolo Squatriti, Alessandro Sebastiani and David Fredrick, whose guidance and advice were fundamental in the original conception of this work as part of my doctoral dissertation at the University of Michigan.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.