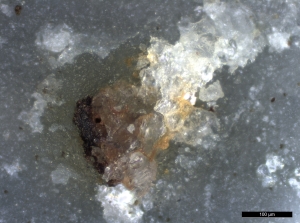

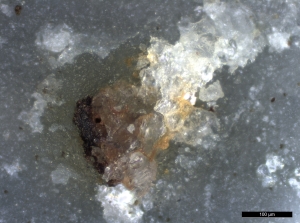

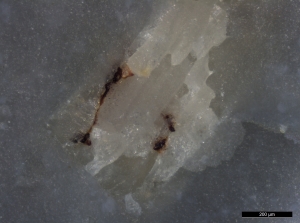

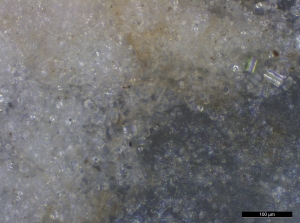

The raw material used to produce the experimental flakes was examined microscopically to observe any natural irregularities that might be mistaken for residues. It was found that the Wolds flint contained crystal inclusions of two types: 1) irregular white to brown angular crystals (Figure 15), and 2) rectangular linearly arranged crystals (Figure 16). These crystalline materials might be misinterpreted as bone or antler, highlighting the need to study raw stone materials and their natural irregularities prior to analysis of archaeological stone tools.

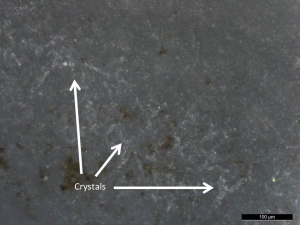

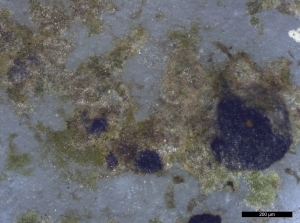

After 11 months, heavy crystal formation on the soil surface of the wetland unit 2 was visible macroscopically (Figure 16), and microscopic examination of flakes from this unit shows that authigenic microcrystals also grew on all flakes, including the blank control (Figure 17). These crystals were not removed by the usual cleaning process with a stream of ultrapure water. These microcrystals are possibly a form of gypsum (CaSO4.2H2O), based on the rosette and lath-shaped growth habit observed, that is identical in appearance to gypsum (Shih et al. 2005, 257). Crystal formation was so heavy under and around fish-scale residues on the flake buried in the wetland for 11 months, it was visible macroscopically as a white powdery material (Figure 18); microscopically, the individual crystals were distinguishable (Figure 19).

Changes to blank flakes resulting from burial condition were documented. Soil residues from the burial environment were found on all six controls from all units and burial intervals. Such soil residues could hypothetically be mistaken as potential anthropogenic residues. In particular, the soil residues seen adhering to the control flakes buried in the dry land for both 1 month and 11 months were concentrated along one edge in a way that might be misinterpreted as a residue from tool use. The blank flake buried in the alkaline unit 3 for 1 month showed a green growth on the flint surface (Figure 21). This could be a chlorophyll-containing lichen, although hyphae comprising the fungal symbiont were not immediately apparent under the microscope.

All blank control flakes buried alongside the residue-containing flakes in each burial set were found to have no residues. This means no residue transfer occurred owing to horizontal movement of residues from experimental pieces to the controls during burial.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.