Table 5 is a visual presentation of the results from each individual flake included in the experiment. The two left columns of the table show residues from the reference collection in the fresh dried state. In order to capture the variability of each residue type better, two examples of each reference collection residue are included in the two left columns. The columns to the right show the degree of preservation for each residue type in each experimental set.

The residue types that survived across all burial conditions and time intervals were: softwood tissue, resin, bird feathers, squirrel hair, and red ochre. The tree resin and red ochre preserved best, both scoring 4 out of 5 on the preservation index in every burial condition. Although it is not possible to carry out a burial experiment of comparable time depth to archaeological material, these results suggest that these residue types hold the greatest potential for being preserved archaeologically at Star Carr. The residue types that exhibited the least preservation overall were bone, antler, muscle, and potato starch. The assessment of preservation is clearly linked to the visual identifiability of the residue – if the residue is not morphologically recognisable from the soil and the stone substrate, preservation cannot be accurately determined. For instance, bone, antler, and muscle residues lack diagnostic traits and thus determining their level of preservation was a challenge.

Keratinised remains, including goose feather barbules and squirrel hair, survived in all burial units, retaining microscopically diagnostic structural features. Plant remains that survived and maintained diagnostic features in all burial conditions included softwood tracheids and reed plant cells. The pattern of preservation documented for the Cyprinid fish scales requires some comment. As a part of the suite of fish residues, including skin and blood, the scales were unequally distributed when applied to flakes, with some tools unfortunately retaining no scales during butchery of the fish. This accounts for their coincidental presence in the wetland after 11 months' burial, but absence after only 1 month burial (see Table 5). Given that fish scales were found after burial in all three units, this pattern of preservation suggests that fish scales would probably have been observed on all flakes if they had been present on all flakes after butchery.

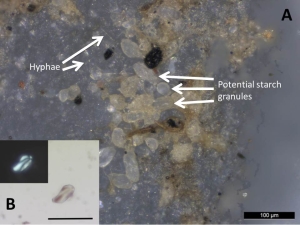

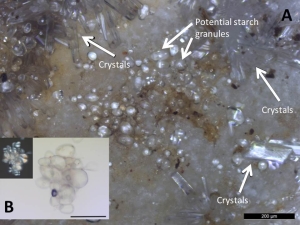

Suspected starch granules were found on two flakes used on potato – one flake was buried in unit 1 dry land and the other flake buried in unit 2 wetland for 1 month each. An extra test involving extraction and viewing with transmitted VLM was conducted to check if these ovate and round residues were indeed starch granules. 40 μl deionised water was applied to the location on the flake where suspected starch was documented previously with reflected VLM. The plastic pipette was agitated, the mixture aspirated, and applied to a glass slide which was allowed to dry. 20 μl of mounting medium of 50/50 glycerol/deionised water was applied and mixed with the dry extract. Glass cover slips were applied and affixed with clear nail varnish from a new sealed bottle, using a new toothpick for each insertion into the nail varnish bottle to prevent cross-contamination (Kooyman 2015). Prepared slides were viewed with a Zeiss Axio Scope.A1 at magnifications up to 400x. The presence of potato starch on the flakes was confirmed (see Figures 13 and 14), and presentation of the full extent of the extinction cross and rotation of the arms was observed with transmitted VLM. Interestingly, clear lath-shaped authigenic crystals were found in association with the potato starch granules on the flake buried in the wetland for 1 month (Figure 14A). The presence of these crystals may have created a microenvironment that facilitated starch preservation.

Table 6 shows the preservation index value (Langejans 2010) that was assigned to each flake after burial, giving an estimate of residue survival throughout the experiment by residue type, burial type, and burial duration. Table 6 does not capture the difficulties encountered with assigning a preservation value to each residue after burial, since in some cases it was very hard to determine if the original residue had in fact been located, owing to the combination of lack of diagnostic traits and degradation. Another issue encountered was the fact that all of the residue types used in the experiment (with the exception of red ochre) actually represent a suite or complex of residues, not one homogeneous residue type. For instance, the reeds contained wax cuticle, epidermal tissue, parenchyma, vascular tissues (tracheids, vessel elements), and green chlorophyll pigments, among other components. In terms of experimental design, it would have been preferable to isolate individual residues to a cellular level. However, isolation and separation of the components of residue suites might pose difficulties in terms of time and technological requirements, since biological materials used prehistorically are all composites that contain a variety of cell types and tissues.

| Reference collection | Dry land 1 month | Dry land 11 months | Wetland 1 month | Wetland 11 months | Alkaline 1 month | Alkaline 11 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Antler | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Muscle | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Fish | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Bird | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Squirrel | 5 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Potato | 5 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Reeds | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Softwood | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Hardwood | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Resin | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Red ochre | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Control | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.