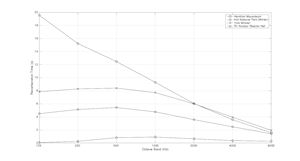

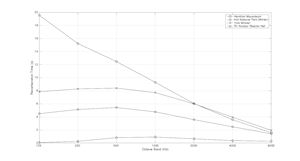

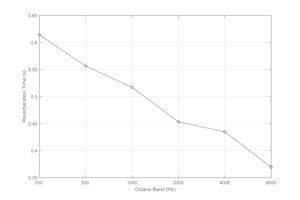

The fundamental quantity used to characterise, define or gain information about the acoustic qualities of a particular space that can be obtained from an impulse response is reverberation time. Reverberation time (or RT60) is formally defined as the time it takes (in seconds) for a steady state signal to attenuate by 60 decibels once the sound source has stopped (Sabine 1922). Perceptually, RT60 is the formal quantity we associate with a space we might consider as being echoey or spacious. Such a space might have an RT60 value of 2 seconds or more. A space considered as being dry or dead sounding might have an RT60 value of less than 0.5 second. An anechoic space is specially designed to absorb all sound and so would ideally have an RT60 of zero seconds. Reverberation time varies with frequency, and is typically quoted in octave bands (the audio spectrum divided into 10 octaves between 20Hz and 20kHz, with an octave defined as a doubling in frequency). Figure 10 shows RT60 values, quoted for each octave band, for a range of spaces found on OpenAIR.

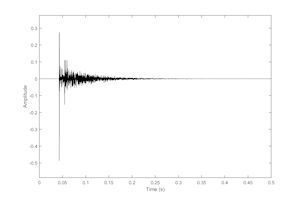

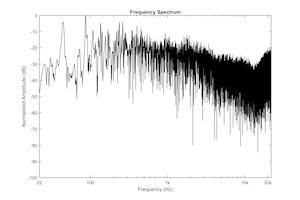

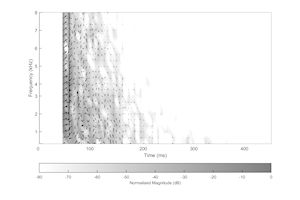

Other acoustic parameters can also be derived from an impulse response measurement, and are commonly used to provide additional detail in the acoustic characterisation of a particular space. These parameters form an important part of the modern architectural design process and have been documented in the relevant international standard (ISO3382-1 2009). They have also been adopted in studies relating to acoustic heritage as they are able to give insight into, for instance, the intelligibility of speech or music in a particular space. However, it is also possible to interrogate this digital data in other meaningful ways. Analysing the frequency content of such time-varying impulse response measurements helps to reveal how low frequency sound behaves, and whether there are specific resonances that might act to influence or colour how sound is perceived. If spatial impulse response measurements are available, as obtained from a Soundfield microphone, it is also possible to conduct a reflection analysis to detect from which directions, and hence from which walls, specific sound reflections come from. Again, such information can help to reveal how humans might interact with such sonic features or the acoustic consequences of how a space is changed architecturally over its lifetime. Figures 11–14 show a frequency and reflection analysis for the main chamber in Maes Howe passage tomb (Murphy 2005), a small but highly reflective and resonant space.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.