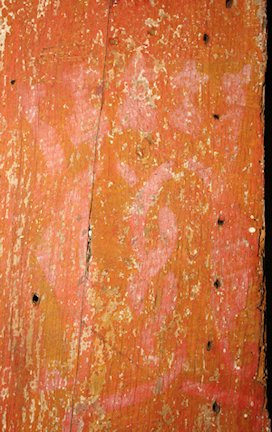

The recording, analysis and conservation work in the Guildhall revealed that originally, the vertical timber studs of both walls were painted bright red and decorated with an alternating series of three different stencilled motifs in white and a deeper shade of red (Figure 30a-d). These were a cinquefoil rosette, a symbol usually associated with the Virgin and the Virgin Mary monogram (a crown over the letter M), together with the IHS monogram (representing Jesus Christ). The lintel over the doorway featured alternating bands of bright red and medium blue pigments, also found across the panels and timbers of the south wall. The bresummer at the top of the wall was painted deep red. Perry Lithgow have created a reconstruction drawing of the medieval appearance of this elevation (Figure 31).

Alternating vertical bands of bright red and blue also formed the backdrop to the painted figures on the south wall. Slight traces of additional painted detail remaining on the bright red vertical timbers suggest that they may also have been decorated with the same three stencilled motifs as the east wall (Lithgow and Perry 2016, 17). Antiquarian studies had suggested that in the centre of the south wall was a Crucifixion, flanked by the Virgin and St John the Baptist (see Figure 21). Although images of the Crucifixion usually feature the Virgin and St. John the Evangelist, the inclusion of St John the Baptist in the Guildhall painting had been presumed to reflect the fact that in the early decades of the 14th century, the Holy Cross guild amalgamated with the guilds of the Virgin and St John the Baptist, which had been based in the parish church. In 1403 the guild of the Holy Cross, the Blessed Virgin Mary and St John the Baptist was granted a formal charter by Henry VI, which was re-confirmed in 1429 (The National Archives C66/369 m.13; C66/424 m.5; Macdonald 2007; 2012; 15-16). John the Baptist is also the featured on the guild seal (see above, Figure 22). However, Rutherfoord's (2004) analysis had revealed traces of God the Father seated behind the Crucified Christ and in the early stages of the conservation project the team questioned whether this might reflect a subsequent alteration of the early 15th-century scheme in the 1490s, when Hugh Clopton's will and contemporary guild accounts suggest an intention to re-dedicate the guild as 'the Guild of the Holy Trinity, the Blessed Mary the Virgin and St John the Baptist' (SCLA DR624/13(ii); SCLA BRT1/3/105; Giles et al. 2012, section 4.5).

However, as soon as Perry Lithgow's detailed analysis commenced, it became apparent that the south wall composition was of one date (see Figure 32). In the centre is God the Father, dressed in a white mantle with ermine lining, seated on a throne with the Crucified Christ between his knees. God's right hand is raised in blessing, while his left hand supports the crosspiece of the Crucifixion. Beneath the cross is an orbis terrarium: orb or circle of the lands; a type of world map with the letter 'T' inside an 'O'. Although no trace of a Dove, the symbol of the Holy Spirit survives, it is likely that it was located directly above Christ's head. The Trinity scene has a deep green background with exquisite small gilt oak-leaf embellishments. The inclusion of flanking figures of the Virgin and St John make this an unusual iconography. The closest parallel for this combination of Crucifixion/rood imagery and the Trinity is a 15th-century painted piscina in Lichfield cathedral (Rosewell 2008, 172), although a close parallel for the Trinity appears to be a brass at Great Tew church (Oxon), and the exquisitely illuminated Register of the Guild of the Holy and Undivided Trinity at Luton, Beds (Marks 1998).

The initial reconstruction drawing was produced to scale, based on the measured survey of the south wall using rectified photography (Figure 33). Although it was initially proposed to create a virtual representation of the painting, the fragmentary nature of the surviving paintings and the need for artistic input into the process led to the appointment of archaeological artist Dom Andrews, who works regularly with the Centre for the Study of Christianity and Culture on the reconstruction of medieval wall paintings. The image itself was painted in acrylics, enabling changes to be made to the image as new discoveries emerged during Perry Lithgow's conservation work.

Throughout early February, Lithgow, Giles and Andrews debated missing elements of the figures flanking the Trinity, drawing on contemporary images such as the guild seal and the wall paintings at St Laurence, Combe Longa (Oxon). Comparative images of the Virgin were used to inform the exact positioning of her hands, while extensive discussion about the position of St John the Baptist's hands, especially around his right (the viewer's left) shoulder, resulted in the conclusion that what had been presumed to be a hand was in fact a knot or fold of drapery. In early March the reason for this confusion became apparent. Digital documentation using raking light and UV illumination had raised questions about the possible presence of further figures in the infill panels adjacent to the Virgin and St John. After permission was then granted by Historic England for the further removal of selected areas of the red and yellow ochre scheme, and to the right of St John, the head of a bearded saint emerged. Further investigation revealed this clearly to be St John the Baptist, supporting a cross staff and cradling a book and the Lamb of God (Figure 34). This confirmed the identification of the figure to the right of the Cross as St John the Evangelist. Despite close analysis, no flanking figure on the timber adjacent to the Virgin was discovered.

The decision to produce the reconstruction drawing in acrylics and the constant dialogue between Lithgow and Andrews meant that the painting could be adapted to include new discoveries, including the figure of St John the Baptist (Figure 35). This flexibility was made because of the shared scholarly aims of the conservators, academics, project team, KES and Historic England. These new discoveries have shed important light on scholarly understanding of the original painting. The method of using the close studs and infill panels of the wall of a 'secular' building as a mural canvas for images of saints has close parallels with the ways in which similar images were created on panelled screens in contemporary parish churches (Cragoe 2005; Duffy 1997; Vallance 1936; 1947). The iconography of the Trinity, flanked by the Virgin and St John the Evangelist, is more conventional and allies the scheme firmly with the wider context of late medieval wall painting in Warwickshire (Davidson and Alexander 1985) and with other guild art, such as the Luton Guild Register (Marks 1998; 2004).

Conservation analysis revealed the east wall of the Guildhall chapel to be an important part of the wider decorative scheme within the Guildhall (Lithgow and Perry 2016, 1-3; fig. 36a and b). Analysis of the first-floor chamber of the South Wing has revealed an elaborate scheme of Tudor Roses in the west gable wall, and painted replica textile hangings, preserved across the plaster panels and studs of the north wall, which are likely to have extended around the entire room. At the top of the wall is a continuous valance of shield-shaped designs, with alternating red and white backgrounds adorned with various crescent and keyhole designs in red and black. The wall below features alternating vertical bands of red and black, with a pattern of foliate and branch-like motifs. The paintings appear to date from the early 16th century and reflect the widespread practice of replicating expensive textiles in painted schemes, common to domestic and public buildings of the period (Kirkham 2010).

Nick Molyneux of Historic England has suggested that the branch-like designs may well represented the 'ragged staff' often used by the Earls of Warwick as part of their heraldry and reinforces the close local and regional connections of the guild of the Holy Cross with the Earls of Warwick and Beauchamp affinity, evident in the heraldry of the Guildhall chapel. It seems highly likely that the Guildhall itself would have been similarly decorated, perhaps with a combination of textiles, painted cloths and paintings, which have not survived or, at least, have not been uncovered, during restoration work. It is only in the lower Guildhall, in the spaces once associated with a small chapel, that painted evidence of the devotional focus of the Holy Cross Guild, survives.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.