The village of Mid-Lavant lies three miles (4.8km) north of Chichester along a main road leading north to South Harting and Midhurst. It is a long, dispersed village built at a crossing point of the Lavant River. Within the village, the parish church of St Nicholas is much altered from its medieval and early modern form by 19th-century intervention that has played a signal role in the reorganisation of the church's architecture and contents. This was a small, originally two-celled, aisleless Norman church used as their patronal chapel during the 16th-18th centuries by the influential May family of nearby Rawmere House (for the 17th-century Mays see Thomas-Stanford 1910; Fletcher 1975, 24-40, 252-59, 310-40; Crook 1983; Institute of Historical Research 2016). The exterior of the church is shown in Figure 2 and the current interior in Figure 3.

Dame Mary's effigy and tomb was created by John Bushnell, the famous if eccentric late 17th-century sculptor, and set up in the chancel of the church in 1676 (Esdaile 1926, 21-45; Whinney 1992, 94-102). It had been commissioned by Dame Mary May for herself, possibly, as Bayley, who wrote about the tomb in the 1960s speculates, with the assistance and on the advice of her husband's uncle Hugh May, one of Charles II's court architects and a contemporary and colleague of Sir Christopher Wren (Bayley 1969, 1-2). In its present form it appears as the sculpted effigy of Dame Mary reclining on a black marble ledge with her epitaph below inscribed within a Baroque cartouche. The epitaph reads:

Here/Lies the Body of Dame Mary May, Second/wife to Sr John May of Rawmere, the/only surviving Sister and Sole Heire unto/Sr John Morley of Broom and Daughter to Sr John Morley of Chichester, Son to/Sr Edward Morley a second Brother of the Family of Halnaker Place. Piously/contemplating ye uncertainty of this life/among other solemn preparations for her/Funerall Obsequies, Shee erected this/monument in ye time of her Life in ye/year of Our LORD 1676, shee departed this life in ye year of Our LORD 1681/in ye 41st year of her Age.

As with many small Downland Sussex churches, the floor space within both the chancel and the nave is extremely limited. As a result many of the local gentry established their pews in the chancel, as the Mays did in this case. The monument at the same time is recorded as being sited close at hand in the north-east chancel corner, as is commonplace in this region for important patronal tombs (for general accounts of Sussex churches and St Nicholas in particular see Salzmann 1953; Pevsner and Nairn 1965; Allen 2012; see also Aldsworth 1982, 231-4).

As the epigraphy reveals, this implies that at the same time Dame Mary May's living body would attend church and be seated in the chancel in the May's gentry pew near her own effigy. Onlookers and other family members seated nearby would therefore be able to view Dame Mary's dead, inanimate sculptural body and her living animate physical body side by side up until her death. This pre-emptive erection of their own memorial monuments by those who were intending in time to be buried in the vault below was by no means uncommon during the 16th and 17th centuries but these were generally commissioned by gentlemen for themselves (Llewellyn 2000, 53-8). In the rare cases where women commissioned them (as with the tombs of Sir William and Lady Mary Uvedale, St Nicholas', Wickham, Hampshire, and Adrian and Mary Stoughton, St Andrew's, West Stoke, West Sussex) they were almost invariably effigially portrayed with their husbands (Jones 2013b, 79-91). This sole representation argues considerable social and personal self-confidence on the part of Lady May.

With regard to the monument's original form it is likely that the May tomb was a version of the Ashburnham tomb from Ashburnham, East Sussex (see Figure 4), sculpted by John Bushnell for Sir William Ashburnham in 1675 just prior to the May tomb. This seems to have been a model for a series of later monuments, most of which no longer survive. Certainly the effigy of Lady Jane Ashburnham, Countess of Marlborough, over whom Sir William mourns is almost the twin of Dame Mary's, which suggests that both were quasi-generic portraits (Esdaile 1941, 129-32).

The form of the Ashburnham monument indicates the sort of sculptural surround that Dame Mary's tomb would have possessed initially, although it is most unlikely that her husband was figuratively represented other than as a passing reference in Dame Mary's epitaph. From this, and from a 1782 drawing by Grimm in the Burrell Collection in the British Museum (Add. MS. 5677 fol. 77), one can infer that the May tomb started its life complete with a canopy and curtains, together with an urn, putti, heraldic escutcheon, sarcophagus, marble lid and inscription. In other words it was a much larger and more imposing monument than its present stripped-down version suggests (Whinney 1992, 99-100; Bayley 1969, 3-4).

As the epitaph states Dame Mary died of smallpox five years later in 1681 and, before she expired, she is said to have asked her family to alter her effigy to reflect her dying bodily condition. Bayley cites Salzmann's 1953 Victoria County History entry for Mid-Lavant and an 1893 letter to Revd James Fraser from W.R.W. Stephens, the vicar of St Nicholas, as a confirmation that this request was made, although, as Dame Mary's will is lost, the story was evidently regarded as being somewhat apocryphal (Bayley 1969, 5-6; Salzmann 1953, 106, footnote 54; Sussex Archaeological Society 1932, ii). As a result, various local legends sprung up concerning the treatment of the monument since tradition holds that after this her relatives faithfully obeyed her dying instructions and the effigy's fleshy areas were stippled with pock-marks. By 1969 this tradition had been challenged, especially by the Reverend T.D.S. Bayley (Bayley 1969, 1-9).

Bayley's essay in the Sussex Archaeological Collections (1969), is extensively researched and gives (perhaps obliquely) some insight into the strength of character shown by Dame Mary. He cites the research notes of a colleague, Reverend J.T. Drinkall, who had investigated the circumstances surrounding the visit of Thomas Cowley, gentleman and bachelor and a cousin to Dame Mary's deceased husband Sir John, who arrived in 1673 at Rawmere a year after Sir John's death. He apparently carried with him a marriage licence and was intending to ask the wealthy widow to marry him. Bayley and Drinkall seem to have been dismayed to discover his suit was rejected:

'One may pause to wonder why a well-connected widow of 36 did not consider marrying again rather than devote her energies to setting up such a lugubrious memorial of herself' (Bayley 1969, 3).

Bayley also seems to have taken at face value comments left in Cowley's diary on her financial management of a valuable Lincolnshire property she had inherited from her own family. After his rejection and after he himself inherited the property from her after her death, Cowley wrote:

'…this estate… was preserved from all harm… till (Sir Edward Morley's) grand-daughter, a vain and profligate woman Mary Morley began to mortgage it' (Bayley 1969, citing Drinkall citing Cowley).

Bayley's moral disapproval of Mary's behaviour and character might nowadays be interpreted as containing a certain amount of chauvinistic bias, perhaps not untypical of his generation of scholars. In fact, both today and in the 17th century it may have been quite valid to question the motives of a family relation who, without any preamble, turns up at the house of a recently widowed heiress with a marriage licence tucked in his pocket. Certainly Mary May's dismissal of Cowley argues considerable independence of mind and maybe even some determination to enjoy her independent status as a widow. As mentioned above, her social confidence in herself as a local figure must have been substantial for her to envisage commissioning and erecting her own 'lugubrious memorial' from an artist whose reputation in the 1670s was still highly respected (Whinney 1992, 96-100).

Returning to the memorial itself, on close inspection its condition does seem to show some damage to the head but to the naked eye it is difficult to tell how this came about. This therefore is at the heart of the research question and explains why we considered RTI might be applicable. We asked, did this subsequent pock-marking happen and was the monument deliberately altered? The face appears heavily marked but, as Bayley, who never actually saw the effigy, suggests, this could be the result of later accidents (Bayley 1969, 6). Certainly Bushnell could not have carried out the marking, as the monument was set up five years before Dame Mary contracted smallpox. If the effigy had indeed been adapted, obviously the inference would be that her dead/inanimate body was, as requested in the will, intentionally made to resemble her dying physical body.

Regarding the subsequent history of this monument; in the 17th century, St Nicholas' church was adapted at the instigation of the Mays from its medieval form by the addition of a gallery, a new porch and several new round-headed windows. In the 1780s the Mays left and the third Duke of Richmond, from his house at Goodwood, acquired the estate and became Mid-Lavant's patron (Dallaway 1815, 113). Shortly afterwards the May tomb was moved from the chancel and set up against the south wall of the nave (Bayley 1969, 3-4). As a result Dame Mary's sculptural body was demoted from its primary place of honour. In its new position it became more physically accessible to ordinary parishioners in the nave and, in this way, its role as a separated and privileged elite memorial was negated. It became touchable and close, no longer a distant object for social veneration. Moreover it also lost its religious associations by its removal from its position near the altar.

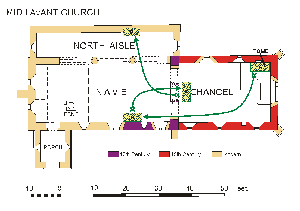

In 1844-5 a series of changes commenced when the church was enlarged by the addition of the north aisle and in 1872 much more drastic alterations were effected by Reverend W.R.W. Stephens and his architect Henry Woodyer (Pevsner and Nairn 1965, 260). During these, Dame Mary's monument was moved and deposited in the May vault under the chancel. The primary reason given by Stephens was that the tomb interfered with the installation of new windows and the pewing arrangements he had devised (Bayley 1969, 4-5), but as there was room for it to be removed to the new north aisle its banishment to the vault seems to have been unnecessarily final. It implies that the dead, inanimate and possibly disfigured body may have been viscerally understood as repellent and spiritually unsuitable to 19th-century religious ideology. The whole thing would also have to have been physically dismantled in order to fit into the vault, thereby annihilating its unity both as a monument and as a framework for an important figurative sculpture. Figure 5 traces the movement of the monument in the church.

Dame Mary's effigy, clad classically in a revealing garment, may, in addition, have been considered transgressive in terms of its gendered claims to memorialisation and also perhaps sexually transgressive as well (see Figure 6). If this was the case, was its removal the result of an emotional and physical reaction to it whereby the effigy was understood to be lifeless but was subliminally reacted to as if alive and active? Moreover alive, active and possibly disfigured.

In 1981 the architect George Claridge renovated the church and Dame Mary's tomb was rescued and placed in a niche in the north aisle, having been shorn down to its effigy and epigraphic marble cartouche. At this point one can observe that Dame Mary's dead inanimate body was being resurrected now more as an artwork rather than an active, working memorial. This is underlined by the addition of a framed information panel that concentrates on the biographies of Bushnell and Hugh May, Dame Mary's architect uncle, both of whom are understood as influential late 17th-century artists. At this stage in the effigy's journey it is possible to see a form of 20th-century intellectual disembodiment being practised. Now one can perceive that the tomb's gender has been neutralised by the way it is presented since it merely becomes classical subject matter for the more important male artists being considered, while Dame Mary herself retreats into the background.

However, the research question remains and the business of her disfigurement is still unresolved. This evidently has played a part in her treatment in the past. Having discussed some of the biographical, spatial and theoretical aspects of the tomb, as we did before we applied any digital techniques, we turned to the problem of whether this disfigurement is real or apocryphal and, if real, what does (or did) it signify to its observers? At this point we set up our equipment.

Internet Archaeology is an open access journal based in the Department of Archaeology, University of York. Except where otherwise noted, content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 (CC BY) Unported licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided that attribution to the author(s), the title of the work, the Internet Archaeology journal and the relevant URL/DOI are given.

Terms and Conditions | Legal Statements | Privacy Policy | Cookies Policy | Citing Internet Archaeology

Internet Archaeology content is preserved for the long term with the Archaeology Data Service. Help sustain and support open access publication by donating to our Open Access Archaeology Fund.