Cite this as: West, E., Christie, C., Moretti, D, Scholma-Mason, O. and Smith, A. 2024 A Route Well Travelled. The Archaeology of the A14 Huntingdon to Cambridge Road Improvement Scheme, Internet Archaeology 67. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.67.22

Use top bar to navigate between chapters

The A14 excavations have unearthed a wealth of new evidence for Anglo-Saxon activity, with tentative suggestions of 5th-century occupation, significant early and middle Saxon settlement, and a smaller area of late Saxon settlement. A summary of the evidence for this is presented in Table 5.1 and shown in Figure 5.1, with plans of the main settlements shown in Figures 5.1A to D. The scale of the settlements, particularly at Brampton West (West et al. 2024) and Conington (White et al. 2024), is comparable to the larger and well-known settlements at Mucking (Hamerow 1993), Flixton (Boulter et al. 2012), and West Stow (West 1985). Crucially, the A14 settlements also extend later in time, into the 8th/9th centuries, providing us with the unique opportunity to investigate Anglo-Saxon settlement on a grand scale and over a longer period.

to scroll through plans): Overall plan showing location of all Anglo-Saxon activity across the A14 Scheme, in relation to local sites, topography and transport [Download image]

to scroll through plans): Overall plan showing location of all Anglo-Saxon activity across the A14 Scheme, in relation to local sites, topography and transport [Download image]| Landscape Block | Saxon Settlement? | Any other evidence for Saxon activity |

|---|---|---|

| Alconbury | Settlement 3 - 1 Early Saxon SFB and cooking pit (6th-7th century). | 2 Middle Saxon cremations (8th-10th century). |

| Brampton West | Settlement 203 - early-middle Saxon settlement (6th-8th century) (25 SFBs, two enclosures, 32 structures, one burial, 10 pits/pit groups, and 25 wells). Settlement 3 - early-late Saxon open settlement, but concentrated in middle Saxon period (late 7th-9th century) (67 post-built structures, six SFBs, bounding ditches, one burial, one kiln, 15 pits, and six wells). Settlement 4 - late Saxon enclosed settlement and field system (10th-11th century) (enclosure, field system, five structures). | - |

| West of Ouse | Settlement 5 - five Early Saxon SFBs (6th-7th century). | - |

| Fenstanton Gravels | - | Early Saxon wooden trough in TEA 28 (5th-6th century). Early Saxon Inhumation Burial in TEA 31 (6th-7th century). |

| Conington | Settlement 5 - early Saxon open settlement (24 SFBs, four post-built stuctures, 50 pits, one waterhole/well); early-middle Saxon transitional phase (one enclosure, trackway, three post-pits, four burials); middle Saxon enclosed settlement (four curvilinear enclosures, one with gate structure and burial, eight post-built structures). |

The Anglo-Saxon period in eastern England witnessed a series of significant changes with the collapse of Roman rule in the early 5th century, the arrival of migrants from Europe, and the consolidation of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. This period, particularly the transition from early Anglo-Saxon dispersed settlement into more organised middle Saxon settlement, is often considered to be when 'modern' settlement patterns emerged and, as such, is of great importance in understanding this development (Hoggett 2021). However, such evidence is often hidden underneath modern villages and so there are limited opportunities to explore it, resulting in it being investigated via smaller-scale development-led projects within village cores, or community projects such as the University of Cambridge's CORS test-pitting project and those of Cambridgeshire's JIGSAW local groups, as recorded on the Cambridgeshire Historic Environment Record (CHER). In contrast, the A14 excavations have provided an opportunity to investigate whole settlements, countering some of the issues associated with partial excavation.

Although the A14 scheme lies within the 'eastern' zone of abundant visible Anglo-Saxon settlement (Blair 2018, 27-35), the scale of such Anglo-Saxon settlement in this particular area had not been proven archaeologically prior to these excavations. Centres of activity were known within Huntingdon (the Danish Burh and a cemetery at Whitehill); however, evidence for Anglo-Saxon activity beyond this was relatively sparse. A settlement had been identified at Buckden Gravel Pits towards the western end of the scheme (CHER 00861c, CHER 02498, CHER 02498c) and an extensive cemetery was excavated at Girton College towards the eastern end of the scheme (CHER 05274). Other evidence for Anglo-Saxon activity within and around the A14 corridor comprised individual finds (MCB30043, MCB11606, MCB3393, MCB3510, MCB9553, MCB14763, MCB4557, MCB13327, MCB6319, MCB10668) or field systems (CHER 10826, CHER 15635). More recent archaeological work has, however, exponentially increased our knowledge of Anglo-Saxon activity in the area, most notably with Oxford Archaeology's excavations at Stirtloe Lane and Luck's Lane Buckden, only 2.5km south of the A14 excavations (Clarke 2024); investigations at Loves Farm and Wintringham Park as part of the St Neots town expansion (Hinman and Zant 2018); MOLA's excavations directly to the east of the Brampton West Landscape Block (Atkins and Reid 2022); Albion's excavations at Fenstanton (Albion Archaeology 2022); Cambridge Archaeological Unit's excavations at Northstowe to the north-east of the A14 scheme (Aldred 2021); and Archaeological Solutions' excavations at Harston, south-west of Cambridge (O'Brien 2016). This all indicates that the current farmland of the Cambridgeshire clays was far more heavily settled during the Anglo-Saxon period than was previously thought.

As has been discussed in Chapter 1, the A14 scheme crosses a variety of landscapes across the Cambridgeshire Western Claylands, with river terrace gravels towards the western end and the Great Ouse Valley through the centre. The majority of the identified Anglo-Saxon settlement was located on the river terraces to the west (three of the four settlements and 60% of the SFBs), with the remaining settlement located on the gravel ridge that crosses Conington. The recent excavations of other Anglo-Saxon settlements in the region also show a preference for river terrace gravels, with all four sites sited on the gravels and, in some cases, located on smaller 'outcrops' of gravels (e.g. Albion's Fenstanton site), a trend generally identified in early and middle Anglo-Saxon settlements across Britain (Hamerow 2012, 4). It is likely that transport networks, particularly roads, also influenced the location of the settlements, with Conington adjacent to the 'Via Devana' (the Roman road from Colchester to Chester) and the settlements at Brampton West adjacent to the line of the present A1, which is thought to have had early origins.

This chapter is structured in three sections - the first covers the chronological development of the Anglo-Saxon settlements and a discussion of how this does, or does not, fit into regional and national trends; the second discusses evidence for the different activities taking place within and beyond the settlements; and the third covers the evidence for the people living in this period. Further detail can be found within the landscape block reports, specialist reports and overviews, and project database, all accessed via the digital archive.

Although evidence for both Roman and Anglo-Saxon activity was identified in many of the A14 landscape blocks (Alconbury, Brampton West, West of Ouse, Fenstanton Gravels, and Conington), there are often chronological and/or geographical disconnects between the two, with evidence for Roman to Saxon settlement continuity, and the elusive 5th century, near-impossible to identify. Many of the major Roman sites along the A14 were deserted at, or before, the end of the Roman period - Alconbury 3 was abandoned in the 4th century with the dark earth deposit representing manuring across the area; River Great Ouse 2 was abandoned by the end of the 4th century and the area covered in an alluvial deposit; and all Roman settlements in the Bar Hill Landscape Block were deserted by the beginning of the 4th century with activity apparently contracting north towards Northstowe (Aldred 2021) (Chapter 4). In places there appears to have been a change in land use in the Anglo-Saxon period, most clearly seen at Fenstanton Gravels where radiocarbon dating of a wooden trough (28.566) inserted into a late Iron Age spring/pond returned 5th to 6th century dates (SUERC-98083, SUERC-92383) demonstrating, in this location, a change from late Roman settlement to early Anglo-Saxon agricultural use. This fits the trend across Anglo-Saxon England, with it being more common for Anglo-Saxon settlements to be established on Romano-British farmland than on or adjacent to Romano-British farms or villas (Hamerow 2012, 12).

There is greater evidence for continuity of activity from the late Roman to Anglo-Saxon period, at least in terms of continuity of location and features, in the Conington and Brampton West Landscape Blocks. At Conington, there is the suggestion that some of the late Roman enclosure systems continued into the 5th century and formed defining features within the early Anglo-Saxon settlement. The clearest evidence for this is Ditch 32.24, the recut of the Roman ditch 32.22 to the south of Enclosure 3, which is thought to have at least been open, if not physically recut and extended to the west, in the early Anglo-Saxon period. Moreover, the majority of the Anglo-Saxon settlement at Conington was located to the south of Ditch 32.24 (with the exception of SFB 32.26, see discussion below) and beyond the late Roman enclosures, suggesting that these features remained visible and defining features within the landscape. Similarly at Brampton West, all Settlement BW203 features were located to the west of Roman Linear Boundaries 105 and 205, and outside of the Roman Enclosures 202/203 (with the exception of SFB 12.82, see discussion below). It should be noted, however, that the character of the Roman and Saxon settlements at both Brampton West and Conington were markedly different, indicating that we are not looking at a straightforward case of 'continuity' of settlement or communities, but rather continued use of Roman landscape features.

There is, therefore, evidence for the continuity of certain late Roman landscape features into the Anglo-Saxon period and evidence for the Anglo-Saxon communities referencing (or indeed avoiding) them. Is there, however, any evidence for actual continuity of settlement or communities? This is where the search for the elusive 5th century, and particularly 5th-century settlement, comes into play. Some of the sunken-featured buildings (SFBs) have returned radiocarbon dates that could indicate they are of 5th-century date (Table 5.3), most notably those from West of Ouse 5 and Alconbury 5. Nine of the Conington SFBs returned dates that suggest they may be of 5th to early 6th-century date (SFBs 32.31, 32.32, 32.33, 32.35, 32.38, 32.45, 32.46, 32.48 and 32.49); five from BW203 (SFBs 12.82, 12.137, 12.138, 12.157, and 11.85); and two from BW3 (SFBs 7BC.255 and 7BC.256). Bayesian modelling can refine this for the Conington and Brampton West settlements, and suggests an early 6th century establishment is most likely (Table 5.2). It should be noted, however, that the Bayesian modelling for the Conington Roman settlement suggests that 'Roman' activity 'probably' ended in cal AD 360-500 (68% probability) which, when combined with the modelled 'start'-date for the 'Saxon' activity (cal AD 505-540, 68% probability) suggests broad continuity between the latest Roman and earliest Saxon activity is at least a possibility. Similarly, modelling of the Roman BW203 settlement indicates that 'Roman' activity likely ended in cal AD 260-410 (68% probability) which, when combined with the modelling of the likely start of the Saxon settlement (cal AD 440-515, 68% probability) again perhaps indicates that continuity is a possibility. The evidence from the pottery and small finds, however, also supports an early 6th century date for the establishment of the settlements. At Conington, decorated hand-built pottery was generally scarce and likely of 6th-century date, with only one sherd of mid-late 5th-century pot from Ditch 32.73. Similarly, there were no definite 5th-century objects in the Conington finds assemblage, with only three objects of possible 5th century or later date (F 32781 , F 32027 , and F 32094 ). A similar picture emerges from Brampton West where the pottery assemblages were dominated by 6th and 7th-century vessels, with one possible 5th-century jar from Pit Cluster 11.126, and only a handful of finds of possible 5th-century date (F 12088 , F 11112 , and F 12022 ). The pottery and finds from the dispersed SFBs also suggest a 6th-century date, with 6th-century pottery from SFBs 2.4 and 16.118, and 7th-century loom weights from SFB 16.118.

| Settlement | Modelled start-date (high probability) | Modelled start-date (lower probability) | Modelled end-date (high probability) | Modelled end-date (lower probability) | Span of activity (high probability) | Span of activity (lower probability) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BW203 | TEA10 - cal AD 580-655 (95% probability) | TEA 10 - cal AD 615-650 (68% probability) | TEA 10 - cal AD 690-820 (95% probability) | TEA 10 - cal AD 705-785 (68% probability) | TEA 10 - 45-215 years (95% probability | TEA 10 - 75-170 years (68% probability) |

| TEA 11/12 - cal AD 390-540 (95% probability) | TEA 11/12 - cal AD 440-515 (68% probability) | TEA 11/12 - cal AD 775-955 (95% probability | TEA 11/12 - cal AD 780-875 (68% probability) | TEA 11/12 - 260-530 years (95% probability | TEA 11/12 - 295-435 years (68% probability) | |

| BW3 | cal AD 450-560 (95% probability) | cal AD 500-545 (68% probability) | cal AD 895-970 (45% probability) | cal AD 900-930 (30% probability) | 355-580 years (95% probability) | 365-420 years (31% probability) |

| cal AD 990-1070 (50% probability) | cal AD 995-1040 (38% probability) | 465-535 years (37% probability) | ||||

| BW4 | cal AD 710-1155 (95% probability) | cal AD 915-1050 (68% probability) | cal AD 1050-1470 (95% probability) | cal AD 1060-1125 (21% probability) | 690 years (95% probability) | 40-300 years (68% probability) |

| cal AD 1155-1265 (47% probability) | ||||||

| BW5 | cal AD 730-875 (95% probability) | cal AD 785-865 (68% probability) | cal AD 1215-1345 (95% probability) | cal AD 1230-1280 (68% probability) | 360-565 years (95% probability | 390-490 years (68% probability) |

| C5 | cal AD 470-545 (95% probability) | cal AD 505-540 (68% probability) | cal AD 735-860 (95% probability) | cal AD 790-835 (68% probability) | 205-370 years (95% probability) | 260-325 years (68% probability) |

It is worth discussing SFBs 12.82 and 32.26 separately, as they were in different locations from the other SFBs, 'within' Roman enclosures. SFB 12.82 was built tightly against the eastern boundary of the middle-late Roman Enclosure 203 and within the late Roman Enclosure 202 (Fig. 5.2). The finds assemblage from this structure included Roman objects (a jet ring and 34 sherds of Roman pottery) and 6th to 7th century objects (an antler comb with ring and dot decoration, a bone awl, three ceramic spindle whorls, and 56 sherds of early-middle Saxon pottery). A radiocarbon date of cal AD 220-360 (SUERC-91503) was returned on charcoal from the occupation layer, although this is thought to be residual. At Conington, SFB 32.26 was located within Roman Enclosure 3, to the north of the early Saxon Ditch 32.24 (Fig. 5.3). Finds included Roman objects (window glass and 108 Roman pottery sherds) and Anglo-Saxon objects (130 pottery sherds, a bone comb fragment, an iron woolcomb, a bone needle, a pin beater, and five loom weights). A radiocarbon date of cal AD 660-780 (SUERC-93212) was obtained on porcine bone from the fill that sealed the structure, providing a terminus ante-quem. Although these structures were clearly 'different' in some way, the presence of significant quantities of Anglo-Saxon finds and the morphology of the structures suggests that it is most likely that the Roman enclosures were extant to some degree, rather than that the structures were themselves of late Roman or 5th-century date.

Early Anglo-Saxon settlement becomes more visible in the 6th and 7th centuries, predominantly in the form of Sunken-Featured Buildings (SFBs). A total of 62 SFBs were identified across the A14 scheme - one in the Alconbury Landscape Block; five in the West of Ouse Landscape Block; six in BW3; 26 in BW203; and 24 in C5 (Table 5.3; Fig. 5.4). This adds to other known examples in the immediate area, including the four to the west of Brampton which could, based on their geographical proximity, have formed part of BW203 (Atkins and Reid 2022), and the seven at Stirtloe Lane/Luck's Lane (Clarke 2024). SFBs are a distinctive building type found in north-west Europe across the 5th to late 7th centuries. They are debated structures with questions over their morphology (sunken or suspended floors) and function (small-scale craft/industrial building, for grain storage, or other functions) (Tipper 2004). The excavation of a large number of these structures, as part of the same project, can help attempt to answer some of these questions.

Isolated SFBs (2.5, 14.117 and 15.45), small clusters of SFBs (16.118, 16.119 and 16.120), and larger groups, such as those in the Conington and Brampton West settlements, were identified across the A14. They were all located on the gravel terraces, with those at Conington focused on the gravel ridge that crossed the site, and the three in TEA 16 focused on the higher gravels before the ground dipped towards the river. This likely reflects a conscious decision to site such SFBs on gravel deposits, a decision reflected in the other regional Anglo-Saxon settlements and more widely across Britain. Many of the SFBs were sited in relation to prehistoric monuments with four of the six 'dispersed' SFBs located in apparent reference to such monuments - SFB 2.5 was 25m to the north-west of the late Neolithic/early Bronze Age henge (Alconbury Monument 1); and SFBs 16.118-16.120 were 45m to the east of the early Bronze Age barrow (WOO Monument 2). There is also evidence for the siting of some of the Brampton West SFBs in relation to prehistoric monuments, with ten of the BW203 SFBs adjacent to the early-middle Bronze Age barrow (BW Monument 200) and no Saxon features located within the interior of the monument itself. This all suggests that, firstly, the earthworks associated with these prehistoric monuments were visible in the Anglo-Saxon period and, more significantly, that some 'importance' was attached to them. It is noteworthy that the A14 examples show a preference for siting SFBs close to prehistoric monuments, but not physically reusing them, with no examples positioned within the 'interior' of the monuments. The appropriation of early prehistoric monuments in early-middle Anglo-Saxon England is a well-discussed phenomenon in relation to burial sites, churches, and political centres, but has, until recently, been less well studied in settlement contexts (Crewe 2011). Conversely, there appeared to be a desire to position the SFBs away from the earthworks of Roman features, reflected in their positioning outside of the Roman enclosures in Conington and BW203, away from nearby Roman settlements at BW3, and with SFB 15.45 located to the south of (and outside) Roman Enclosure WOO3. The exception was SFB 14.117, which was positioned between the roadside ditches of the Roman Trackway WOO2.

The SFBs were sub-rectangular to sub-oval in shape and ranged in size from small (2-3m in length) to medium (3-4m in length), to large (4-5m in length), with eleven examples of very large structures (over 5m in length) (Table 5.4; Figs 5.5 and 5.6). There was a higher concentration of larger SFBs in BW203 than in the other areas (31% fitting into the 'very large' category), with four examples at over 6m in length (10.536, 10.373, 11.85 and 10.536). No clear chronological difference in size could be identified, although the only definitely later structure (7BC.347) was a larger example (6.2m by 4.3m), and there is a general trend, identified at West Stow and Mucking, for very large SFBs, i.e. over 5m in length, to be of 7th century or later date (Hamerow 2012, 54). The depths of these structures also varied from 0.06m to 0.83m, although this was likely the result of vertical truncation from ploughing rather than reflecting the 'true' depth of the structures.

| Settlement | Size | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small (2-3m length) | Medium (3-4m length) | Large (4-5m length) | Very large (5m+ length) | |

| Alconbury 3 | 1 | |||

| West of Ouse 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Brampton West 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | |

| Brampton West 203 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Conington 5 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| TOTAL | 13 | 21 | 17 | 11 |

The number and arrangement of post-holes within SFBs has been used to create classifications (Tipper 2004, 68). The predominant type is the two-post SFB, with the traditional reconstruction showing a pitched roof tent-like structure (see Fig. 5.12). This is reflected in the A14 SFBs, where 25 (40%) had the traditional two-post structure with the posts on the longer axis (Fig. 5.7). Moreover, some of those with additional post-holes clearly had two larger 'gable' posts at either end (e.g. 2.5, 7BC.257, 10.373, 16.120, and 32.35), with poor preservation potentially accounting for those structures where one or no post-holes were recorded (11 examples). Some evidence for the replacement of post-holes was identified at Conington (SFBs 32.37 and 32.44).

The presence or absence of suspended floors is a central feature in debates surrounding SFBs, with the suggestion that, if they had suspended floors, they could have been larger, more expansive, structures than was traditionally thought. The presence or absence of suspended floors could not be definitively deciphered in any of the A14 SFBs, with no evidence for floor planks but, equally, no evidence for entrances or wear on the floor as might be expected for the sunken-floor model. Instead, the majority of the structures simply comprised the (truncated) cut for the pit and post-holes. This is with the exception of the middle Saxon SFB 7BC.237 (BW3), which had a beam-slot along the western side, possibly to support a suspended floor (Fig. 5.8). This structure was, however, different from the other A14 SFBs, with its later radiocarbon date (7th-9th century) and positioning in association with a middle Saxon post-built structure, such that it should be treated as an exception rather than the rule.

Surviving structural materials associated with the SFBs were rare. Small fragments of daub were uncovered in some of the BW203 SFBs, while a timber from a well in BW4 may have been a step leading into an SFB (F73003) (Goodburn 2024c). Micromorphological analysis provides further insights into the structure of SFBs, with the presence of textural pedofeatures in the dark soil fill of SFB 11.124 potentially indicating that it derived from a collapsed turf roof, and a compacted layer of loamy sands and argillic sands, potentially floor construction, in SFB 12.157 (MacPhail 2024b). These are interesting suggestions and indicate that the SFBs may have had turf roofs (as also identified at West Heslerton; Tipper 2004, 80) and constructed floor deposits rather than planked or 'bare' floors, perhaps suggesting there was a wider variety of architectural traditions than is often supposed.

The structures contained up to three fills; 48 examples contained only a single fill, ten contained two fills, and just four contained a tertiary fill. It is generally recognised that primary fills relate to the use-life of the structures (i.e. initial silting through cracks in the floorboards), while the secondary fills represent their backfilling with domestic waste (Tipper 2004), although in many of the A14 examples it is possible that the recorded 'single' fill actually comprised remnants of the 'secondary' backfill into the features rather than true 'primary' fills. Related to this, it should be noted that SFBs often acted as 'traps' for objects, such that finds recovered from their fills do not necessarily directly relate to the use of the structures, but more their later use as rubbish pits. Micromorphological analysis supports this, identifying phosphate (latrine) waste in SFBs 11.124 and 7BC.256, and dumped fire waste in 12.157.

The finds assemblages suggest that textile working was routinely carried out within many of the A14 SFBs (Blackmore 2024b; 2024c; 2024d; 2024e). Finds associated with textile working were recorded in 32 of the SFBs (52%), but this was not evenly distributed throughout. There was a clear focus at Conington where textile working finds were identified in 19 of the 24 SFBs (79%). These finds were focused on weaving and predominantly comprised loom weights (75 fragments from C5, 20 from BW203, and 49 from 16.118), alongside thread pickers and other weaving tools. The earlier stages of textile manufacture, spinning and preparation of the thread, was less well reflected in the assemblages, evidenced by part of a woolcomb from SFB 32.26 (F32644) and spindle whorls (seven from C5, eleven from BW203, and one from Alconbury SFB 2.5). The collection of 49 fragments of loom weights from SFB 16.118, representing 14 loom weights, is particularly interesting (Fig. 5.9). They were very uniform and identified in a cluster in the north-eastern quadrant of the structure and could, therefore, have fallen from a loom left in the abandoned SFB. The fact they were identified in the secondary fill, however, suggests they may instead have been deliberately placed as a closure deposit. Such deposits, although not common, have been identified on other sites, including at Godmanchester (Gibson and Murray 2003).

In contrast to the plentiful evidence in the finds assemblages for textile working, little positive evidence for grain storage was identified. Analysed archaeobotanical samples from the BW203 SFBs contained less than 10 cereal seeds in each, with the archaeobotanical samples from C5 being equally sparse in cereal remains. This is not unusual for SFBs, with assemblages from West Cotton being similarly sparse (Campbell and Robinson 2010, 431). This does not, however, necessarily prove that the structures were not used as grain storage, as all grain may have been removed carefully at the end of the building's life with only (accidentally) charred grain surviving, and so it is still possible that both grain storage and textile-working were carried out within these structures.

It is worth discussing SFB 10.536 (BW203) separately (Figs 5.10-12). This was significantly larger than the other SFBs, measuring 10m by 8m by 1m deep and with two phases of construction. The first phase comprised a cut measuring 10m by 7m by 1m with five post-holes aligned east-west across the centre. Finds recovered from this phase were focused on cloth production (two spindle whorls, part of a bone thread picker, and fragments from four loom weights). Well 10.668 truncated the building. The next phase comprised a secondary SFB cut, following the same outline of the earlier SFB and measuring 10m by 8m by 0.2m deep, with a row of five post-holes along the centre. A wider range of finds was recovered from the secondary cut, including part of a bone pin, a double-sided antler comb, part of a spindle whorl and loom weight, an iron knife, and an iron skewer/spatulate tool. SFBs of this size are incredibly unusual although a similar example (1742) was excavated at Stirtloe Lane and Luck's Lane Buckden (Clarke 2024). This measured 11.5m long by 6.5m wide and 0.8m deep and also comprised two 'phases' of SFB construction, with a well cut through its southern end. The overall size and construction phases of these two SFBs are therefore remarkably similar and raise interesting questions about the particular functions of these larger structures.

Discussion of the early Anglo-Saxon settlement has focused on the SFBs, but pits and wells were also associated with them. These have been identified at C5 (c. 50 pits, including one well and four pit clusters) and BW203 (some of the pits and wells assigned to the 'early-middle Saxon' period would undoubtedly have been associated with the earlier settlement). Five post-built structures at C5 have also been assigned to the early Saxon period, and it is possible that there may have been more but that truncation removed the shallower post-holes. These features are located throughout the C5 and BW203 settlements, with no clear spatial distributions and limited material culture recovered from them. Further detail about these features can be found within the individual landscape block reports.

As we move towards the 'middle Saxon' period, through the later 7th to 9th centuries, settlement was consolidated in three places along the A14 scheme - BW203 and BW3 in Brampton West, and Conington. The character and intensity of this settlement also changed. At Conington, the early Anglo-Saxon SFBs were overlain by a series of ditched enclosures (Fig. 5.1D); at BW203 settlement expanded with a diversification in the types of features (enclosures, post-built structures, pits and wells; Fig. 5.1A); and at BW3 settlement expanded and was formalised with the addition of ditched boundaries and numerous post-built structures (Fig. 5.1B). This could be viewed as part of the 'middle Saxon shuffle' (Arnold and Wardle 1981) - the dislocation of settlement between the dispersed and transitory settlements of the early Anglo-Saxon period and the nucleated and laid-out settlements of the middle Saxon period. However, more recent thinking and, indeed, the evidence from the A14 excavations, suggests that this is too simplistic an explanation.

When considering the A14 settlements against the 'middle Saxon shuffle' theory, it is important to examine the comparative date at which the changes took place, and the backdrop against which these changes occurred. At Conington, the establishment of ditched enclosures began in the second half of the 7th century with Enclosure 8 and Trackway 3. The main phase of enclosure (Enclosures 4-7) followed directly on from these earlier ditches, with radiocarbon dates on cereal grain and animal bone from the fills of Enclosure 4 and 6 ditches returning later 7th to 9th century dates (SUERC-92390; SUERC-92391; SUERC-92401; SUERC-93215; and SUERC-93234). At BW3, the expansion and formalisation of the settlement also took place in the later 7th to early 8th century. At BW203, the expansion and diversification of settlement appears to have taken place slightly earlier in the 7th century, with the settlement largely abandoned by the end of the 8th century. It is important to note, however, that these changes took place on top of already established settlements - spatially, all three 'middle' Saxon settlements were in the same location as their earlier predecessors, and the character of the earlier BW3 and BW203 settlements was similar, though less organised, than the 7th-century developments (post-built structures as part of the early Saxon phase of BW3, and a continuation of SFBs into the 7th-century phase of BW203). Labelling this as a 'shuffle' is therefore incorrect and complements more recent thinking, which suggests there was increased stability of early to middle Saxon settlement (Hoggett 2021), with there being a trend towards clustering and planning in the 7th to 8th centuries. This is reflected at other East Anglian sites such as Bloodmoor Hill in Carlton Colville, where occupation spanned the 6th to 8th centuries, with increased clustering and planning in the 7th to 8th centuries (Lucy et al. 2009). The A14 settlements are therefore important as further examples of sites that effectively disprove the 'middle Saxon' shuffle theory.

So what about the different character of these 'middle' Saxon settlements? One of the major changes was the emergence of ditches and enclosures. This is typical of Saxon settlements, where 'organisation and enclosure' were defining features of the 7th-century settlement revolution (Blair 2018, 149). This happened, to differing degrees and in differing ways, at all three of the A14 settlements.

It was most noticeable at Conington where the principal change was the construction of a series of enclosures directly replacing the early Saxon open settlement (Fig. 5.13). Two phases have been identified; the first (assigned to the early-middle Saxon period, Period 7.2) comprised a series of slight ditches on a north-east to south-west alignment, forming one open enclosure (E8) and a trackway (T3). These were replaced by four larger ditched curvilinear enclosures across the gravel ridge (E4-7), covering an area of approximately 2.2ha. The enclosures were remarkably devoid of contemporary internal features, with only one small post-built structure (32.61) within Enclosure 6. Two structures (32.28 and 32.29) and a small cemetery (C1) were located within Enclosure 5, although these have been assigned to the early-middle Saxon phase (Period 7.2) and so are not necessarily contemporary with the enclosure itself. Instead, the majority of the post-built structures were located along the northern edge of the excavation area, to the north of (and apparently beyond) the enclosures and Trackway 3. The apparent sparseness of these enclosures perhaps suggests they did not function as 'settlement enclosures' as such, but instead may have functioned as livestock corrals or paddocks, as is common in middle Saxon settlements.

Instead, middle Saxon Conington may have functioned as an administrative centre. This is supported by the substantial gated entrance in the southern part of Enclosure 6, which had more of a 'high status' feel to it (Figs 5.14 and 5.15; see White et al. 2024 for further detail). The entrance comprised a gap in the southern Ditch 32.66, initially marked by two post-holes, 320644 and 320804. This was later altered by re-digging the post-holes to form substantially larger sub-circular post-pits 320762 and 320834, measuring 2.9m × 1.8m × 0.86m and 2.6m × 1.3m × 1m respectively. Moreover, the name of the nearby modern settlement 'Conington', a derivative of 'cyninges-tun' with its association with administrative centres, combined with its situation on the gravel ridge and close to the Via Devana, suggests that this site may have represented a potential nodal point of control, established along the borders of middle Anglo-Saxon kingdoms (see further discussion below and in the A14 Landscape Monograph: West et al. forthcoming).

At BW203, two enclosures were established in the early-middle Saxon period - Enclosures 108 and 109 (Fig. 5.16). These were both rectilinear and measured c. 1ha (E108) and c. 0.9ha (E109), aligned north-west to south-east and defined by shallow ditches, potentially functioning as bedding trenches for timber palisades. Stratigraphically, E108 was earlier than E109, although radiocarbon dates from the enclosure ditches returned broadly similar mid-7th to mid-8th century dates, suggesting that both enclosures fell out of use around the same time. This fits with the general trend of the establishment of enclosures from c. 650 (Blair 2018, 148-56). The enclosures functioned as a foci for a variety of settlement activity with post-built structures, SFBs, wells, and pits identified within them, though similar features were also identified outwith the enclosures. In terms of the character of activity, certainly, there is no difference between that within the enclosures as opposed to that outside the enclosures. There is, however, the suggestion, tentatively based on radiocarbon dates, that activity within the enclosures was of a slightly later date than that beyond the enclosures, suggesting that settlement contracted and enclosed in the later phase. Radiocarbon dates from features within the enclosures consistently returned mid-7th to mid-8th century dates (SUERC-92703, SUERC-92704, SUERC_92690, SUERC-92701, SUERC-91500, SUERC-87210, SUERC-92740, SUERC-92693), whereas those from features beyond the enclosures had a far wider range of dates, from the 5th-6th century (SUERC-92710), 6th-7th century (SUERC-87214, SUERC-91397, and SUERC-91146), and up to the 7th-8th century (SUERC-92685, SUERC-92717, SUERC-91145, and SUERC-92349). This suggests that there was an increase in organisation with the establishment of the enclosures in the 7th and 8th centuries, but that this did not totally replace the scattered settlement activity beyond the enclosures.

In contrast, no enclosures were identified at BW3, although ditched boundaries were established in the 8th century (Figs 5.1B and 5.17). Ditches 7BC.252, 7BC.249/7BC.250, and 7BC.251 defined the southern edge of the settlement (with the exception of Structure 7BC.221, south of the boundary), with a 'funnel' entrance leading into the settlement. Radiocarbon dates from these ditches returned consistent dates of cal AD 700-890 (SUERC-91480, SUERC-91415). One other ditched boundary, 7BC.617, was identified in the north-eastern part of the settlement and may have delineated the eastern edge, although this is less certain as confident dating was lacking and it is possible that it was instead a drain rather than a boundary proper, perhaps connecting up to the 'stream' or erosion gully (Ditch 7BC.608) that ran east-west down the slope. Few other ditches were identified across BW3, suggesting instead that fence-lines were used to divide areas. These are often difficult to distinguish from the post-hole structures, with fence-line 7CB.305 being the only identifiable such line.

A total of 112 post-built structures were identified across the settlements (Table 5.5, excluding fence-lines defined as 'structures' on the project database). These were the defining elements of BW3 (67 examples), whereas they were identified in smaller numbers among other features at BW203 (32 examples) and Conington (13 examples; Fig. 5.18). In general, they have been dated to the early-middle and middle Saxon periods, with a particular focus on the later 7th to 9th centuries. A smaller number of early Anglo-Saxon buildings (four from BW3 and four from C5) were identified, alongside two later Anglo-Saxon examples from BW3. These structures pose methodological challenges, particularly at BW3 where the sheer number of post-holes made it difficult to confidently identify all structures. 'Structure' groups have therefore been given for clearly defined structures (where all four walls and internal features are identifiable) and for alignments of post-holes that likely formed part of a structure but where the ground-plan cannot be fully understood. The dating of such structures is also difficult, with only those that are confidently 'middle Saxon' in date having been assigned to Period 7.3, and many others assigned to the wider 'early-middle Saxon' period (7.2). This is particularly because of the difficulties surrounding using radiocarbon dates for dating structures, with dated material from post-holes potentially being older (i.e. in the earth already), contemporary with construction (i.e. fell into the post-packing), or, as is likely often the case, post-demolition and fell into the void left by a post being removed. The discussion that follows is largely focused on the analysis of the BW3 post-built structures, bringing in examples from the other settlements where helpful.

The overwhelming majority of structures were defined solely by the bases of post-holes, small and shallow with no surviving posts, packing deposits, or floor deposits. The only exception to this was Structure 12.120 (BW203) where fragments of Bunter sandstone were identified in some of the post-holes, used as post-pads or packing deposits. Otherwise, the only structural materials were daub fragments. Structures 7BC.246 (BW3) and 32.61 (Conington) were different in construction, with beam-slots delineating parts of the wall lines. With 7BC.246, three beam-slots defined parts of the southern and western sides of the structure (Fig. 5.19), and beam-slots defined parts of the eastern and western sides of Structure 32.61. Both of these structures were slightly later in date, with a radiocarbon date of cereal grain from the beam-slot of Structure 7BC.246 returning a later 8th to 10th century date (SUERC-85539), and the eastern beam-slot of Structure 32.61 truncating the early-middle Saxon Enclosure 8 ditches. This fits with the general trend in Anglo-Saxon architecture, moving from post-construction to post-in-trench construction to, occasionally, sill-beam construction. At BW3, this shift in construction technique does not appear as pronounced as on other Anglo-Saxon sites where, by the 8th to 9th centuries, foundation trenches are present in c. 75% of buildings (Hamerow 2012, 22).

Most structures were rectangular in shape (106/112 were rectangular or 'L-shaped', likely representing the truncated remains of a rectangle), and where 'complete' structures could be identified, they generally measured 10-13m long by 5-6m wide. This is on the larger size of that typically ascribed to early Anglo-Saxon houses (8-10m long, 4-5m wide; Hamerow 2012, 22), although is more typical of middle and later Saxon buildings. The later Saxon buildings at BW3 were slightly larger than the middle Saxon structures, with the late Saxon structures measuring on average 12.8-15m long by 5.6-7m wide. One clear exception to this was middle Saxon Structure 7BC.263, which was significantly longer at 18.7m with a curved internal division at the western end, perhaps indicating a different function (Fig. 5.20). Entrances were difficult to identify and have been suggested for 28 structures but with variable certainty. There were no clear patterns with the entrance positions, with the possible slight preference for a north-east-facing entrance, particularly at BW3 with 5 out of 12 examples (42%). Definite examples of annexes were difficult to identify, only identified in seven of the BW3 structures and none of these as clear as those seen at Yeavering or Cowdery's Down.

Organisation and patterning can be seen in the layout of the post-built structures at BW3. There was a clear preference for an ENE-WSW alignment (24/67, 36%); with a secondary preference for NNW-SSE alignment (15/67, 22%) (Table 5.6). Some of these structures were arranged in lines, with 7BC.221-7BC.226 on the clearest NNW-SSE line in the south-eastern part of the settlement.

| Settlement | Orientation of building | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-S | NNE-SSW | NE-SW | ENE-WSW | E-W | WNW-ESE | NW-SE | NNW-SSE | Unknown | |

| Brampton West 3 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 24 | 5 | 7 | 15 | 2 | |

| Brampton West 203 | 1 | 11 | 13 | 5 | 2 | ||||

| Conington 5 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | ||

| TOTAL (number) | 5 | 8 | 18 | 24 | 18 | 3 | 15 | 18 | 3 |

Beyond this, some of the buildings appear to fit into the 'short perch' grid system, a grid of 4.57m used to lay out Saxon buildings (Blair et al. 2020) (Fig. 5.21). This system has been identified on other middle Saxon sites in Kent, Northumbria, Mercia and East Anglia in the period AD 600-800 and AD 950 onwards and is thought to have originated from ecclesiastical culture, starting in a monastery outside Canterbury and extending out to other churches and monasteries, before moving to settlement settings (e.g. West Fen Road in Ely; Quarrington in Lincolnshire). Although there is no other evidence for BW3 having monastic links, it raises an interesting suggestion about the potential influence of monastic culture on such rural settlements (see further discussion in A14 Landscape Monograph: West et al. forthcoming). This grid system was most obvious in the southern part of BW3, with Structures 7BC.221, 7BC.222, 7BC.223, 7BC.224, 7BC.229, 7BC.245, and 7BC.246. The radiocarbon dates from some of these buildings suggest construction in the AD 600-800 period (more precisely, from around AD 670 onwards) - Structures 7BC.222, 7BC.223, and 7BC.229 returned radiocarbon dates consistent with that dating. The exception was Structure 7BC.246, which returned a radiocarbon date of cal AD 770-980 (SUERC-85539) - this structure was also slightly different in construction (using beam-slots, see above), and so may have been part of a slightly later phase of construction, yet still orientated on the 'short perch' grid system.

Internal post-holes, often forming divisions, were identified in many of the structures. Specifically, 63% contained internal post-holes, with these being identified as forming part of partitions in 33% of the structures. Many of these were parallel or perpendicular to the main structure, with others aligned diagonally. Possible hearths were identified in seven of the BW3 structures, with other internal pits identified in a further twelve BW3 structures. Two hearths were identified in Structure 7BC.222, potentially one in each room. Other internal features within the buildings included individual post-holes and pits, alongside beam-slots in Structures 7BC.271, 7BC.248, and 32.61, which may have supported internal fixtures and fittings.

Structure 7BC.223 was one of the better preserved examples from BW3 and so was heavily radiocarbon-dated to get an idea of the lifespan, and life-cycle, of the building (Fig. 5.22). The stratigraphically earliest post-holes contained material radiocarbon-dated to cal AD 680-880 (SUERC-91411), with the latest post-holes dated to cal AD 770-980 (SUERC-85537) (post-holes on their own contained material dated to cal AD 660-830 (SUERC-91405) and cal AD 700-890 (SUERC-91407)). Bearing in mind the usual caveats surrounding radiocarbon dates from post-hole backfills, it could be tentatively suggested that this building might have been in use from around AD 700 until around AD 800, a period of 100 years or so, or around four generations. In this case, there is evidence for the replacement of posts, indicating continued maintenance, with up to four intercutting posts recorded in places. Examples of building repair have been identified on other sites dating from the 7th century onwards, such as Cowdery's Down, Yeavering, and Flixborough (Hamerow 2012, 35). Elsewhere at BW3 there is evidence for the replacement of buildings on the same footprint of land, most noticeably with Structures 7BC.229, 7BC.230, 7BC.231 and 7BC.232, where 7BC.229 (radiocarbon date of cal AD 670-880, SUERC-91416) was replaced by 7BC.230 and 7BC.231 (radiocarbon date for 7BC.230 of cal AD 770-960, SUERC-91414), which were themselves replaced by Structure 7BC.232, all over the same footprint of land but on different alignments (Fig. 5.23). Clearly, different individuals or families were making different decisions concerning their houses, and whether to repair or rebuild.

The excavation of the apparently 'complete' settlement at BW3 can allow some tentative estimations of population size. Although unlikely to represent the total number, 67 structures were identified. It seems reasonable to suppose that this represents around 70% of the total buildings (assuming some continuation to the north under medieval Settlement 5), placing the total number of buildings at around 95. These buildings would not, however, have all been occupied at once and may not have all been 'residential' structures. The Bayesian modelling suggests that activity at BW3 lasted around 400 years. If we assume a building lasted for around 50 years (two generations, allowing some, such as Structure 7BC.223, to have lasted longer and others, such as 7BC.229-232, to have been replaced more quickly), this would suggest that around 12 buildings were standing at any one point. Settlement at BW3 was not, however, at a consistent level over the 400 year period, with only a handful of structures attributed to the 6th to early 7th century and, equally, only a handful of structures attributed to the 9th century. It could therefore be modelled that 75% of the structures were in use in the AD 650-800 phase, with the remaining 25% of structures in use in the earlier and later phases. This would give, assuming a family of five occupying each structure, population estimates of something akin to that shown in Table 5.7, with a maximum population size of around 120 people. This would place the size of the settlement, at its peak, as comparable to that estimated for West Heslerton and Mucking (Hamerow 2012).

| Period | No. of structures standing | Estimated population |

|---|---|---|

| 500-550 | 4 | 20 |

| 550-600 | 5 | 25 |

| 600-650 | 5 | 25 |

| 650-700 | 24 | 120 |

| 700-750 | 24 | 120 |

| 750-800 | 24 | 120 |

| 800-850 | 5 | 25 |

| 850-900 | 4 | 20 |

Many of these structures would have been used for domestic occupation, although some may have functioned as barns or storehouses. The finds and archaeobotanical assemblages from them, although limited, reflect this. The charred plant remains comprised cereal grains (wheat, rye, barley, etc.), alongside, in some structures, fragments of a bread-like cereal product (González Carretero 2024; 2023). The archaeobotanical assemblage from Structure 7BC.634 was particularly abundant with 23 fragments of cooked charred food, likely bread, demonstrating that the building was used for repetitive food preparation and consumption. The discovery of a tanged flesh fork from the same structure further demonstrates this. Other finds from the Saxon post-built structures reflect the general domestic activities taking place, including a pot hook from Structure 12.178 (BW203), knives from Structures 7BC.262 and 7BC.230 (BW3), and glass vessel sherds from Structures 12.411 and 10.411 (BW203) (Blackmore 2024b). In a very few specific cases, particular functions and activities can be identified within the structures, most noticeably with the bone-working identified in Structure 10.411 (see discussion below).

The middle Saxon settlements were also characterised by a wider variety of types of features including wells and waterholes (17 from BW203, six from BW3, one from C5), pit groups and clusters (for various functions, including waste disposal and extraction, likely of clay and gravel), and burials (one from BW203, one from BW3, and five from C5 - see discussion below). Features with more specific 'functions' were also occasionally identified, with a possible pottery kiln (7BC.235) in BW3 (see discussion below) and an area of dumped oven waste in one of the Enclosure 6 ditches in Conington. Further detail on these is provided in the landscape block reports.

Settlement at both Conington and BW203 had ceased by the 9th century, with late Saxon settlement only identified in the northern part of the Brampton West Landscape Block. This comprised a small-scale continuation of settlement within BW3 in the 9th and 10th centuries, alongside the establishment of two new settlements at BW4 and BW5 in the 10th century. The A14 examples therefore partly support the picture of 9th-century settlement contraction seen elsewhere in eastern England, as at West Fen Road in Ely and Higham Ferrers in Northamptonshire, while the re-emergence of settlement on the same 'site' in the 10th century potentially suggests that, as seen elsewhere, communities were still living in these places but at a smaller scale and with archaeologically 'invisible' buildings (Blair 2018, 285). The later Saxon phase within Brampton West was therefore characterised more by settlement change than settlement contraction.

There is little evidence for any continuity of settlement beyond the end of the 8th century at BW203 (Table 5.2). Furthermore, few features have been assigned to the 8th century phase at BW203 (three wells, a short stretch of ditch, and a pit cluster), with those potentially representing agricultural rather than settlement activity. It seems likely that all settlement at this point moved to the north, around BW3-5. Settlement activity appears to have ended slightly later at Conington, but certainly by the mid-9th century, with one of the latest events comprising the burial of the female on top of the post-pit that once formed part of the gateway (Burial 32.210). Discussion of this is included below, but it is important to note that the burial was radiocarbon dated to cal AD 680-879 (SUERC-75287). It is possible, although currently unproven through archaeological fieldwork, that settlement moved into nearby Conington at this point, with the Domesday Book demonstrating that a settlement was established here by the 11th century. Alternatively, settlement may have moved into Fenstanton or Fen Drayton, both of which are also recorded in the Domesday Book, or the settlement may have been simply abandoned.

Identifying the later Saxon elements within BW3 is tricky, as it partly lay within the area later occupied by the medieval settlement (BW5). Nonetheless, some later Saxon features have been tentatively identified including two post-built structures (7BC.265 and 7BC.290) and individual pits with late Saxon pottery. The Bayesian modelling of BW3 also indicates some continuation into the later Saxon period with the modelling suggesting that activity ended in the 10th to early 11th centuries (Table 5.2).

Of particular interest in the late Saxon period was the emergence of a new settlement - BW4 (Fig. 5.1C). This was located away from BW3, some 180m to the south-east on the lower flatter ground. It was smaller and different in character from the middle Saxon settlements, comprising an enclosure delineating all domestic occupation (Enclosure 7 - the domestic 'core'), with two field systems beyond ('strip' fields or paddocks to the north-east (FS2) and larger open fields to the south-east (FS3)). Activity on the site was relatively closely dated to the later 10th to 12th centuries (Table 5.2), straddling the Norman Conquest and broadly contemporary with the latest phase of BW3 and the earliest phase of BW5. The character of settlement at BW4 was different from that in BW3 and BW5, with the domestic occupation contained and ordered within the enclosure (a form of 'semi-nucleation'), a trackway dividing the enclosure, and beam-slot buildings. A collection of antler-working waste was retrieved from a ditch in the corner of FS3 and may represent post-conquest antler working. It would certainly appear that BW4 was occupied by a separate group of people from those occupying BW3 and BW5, perhaps established as a short-lived demesne farm, in contrast with the longer-lived occupation within BW3 and BW5.

Although discussed more fully in Chapter 6, it is worth noting that Brampton West Settlement 5 was also established in the 10th to 11th centuries, certainly before the Norman Conquest. This is based on the archaeological evidence and Bayesian modelling (Table 5.2). The earliest phase of this settlement comprised a trackway, quarry pits, structures, and pit groups, before it expanded and was formalised in the 12th and 13th centuries. This suggests that there was no chronological gap between BW3 and BW5, but, instead, that the earliest phase of BW5 co-existed with the latest phase of BW3 and that there was a general move of the population from BW3 into BW5.

This section discusses the 'activities' taking place within the Anglo-Saxon settlements just described. It largely focuses on agricultural practices and how these changed over the period, alongside a discussion of other activities such as textile working and the administrative function of middle Saxon Conington.

A transformation in arable practices, leading to agricultural surpluses, is postulated to have taken place in the 'long 8th century' across Anglo-Saxon England (McKerracher 2018; McKerracher and Hamerow 2022), partly driven by the significant social and economic changes instigated by greater political stability and the consolidation of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and lordship. This transformation involved the expansion of arable farming at the expense of pasture with the cultivation of different soils, the adoption of new 'technologies' (i.e. the mouldboard plough), and wider diversification and specialisation of crop choices. Analysis of the archaeobotanical assemblages from the main A14 Anglo-Saxon settlements has added to the discussions surrounding this transformation (see Wallace and Ewens 2024 for more detailed environmental overview).

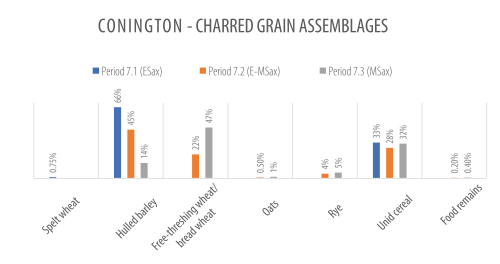

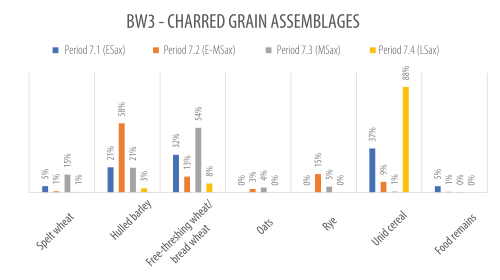

One of the major changes concerns crop choices, with free-threshing bread wheat replacing hulled glume wheat from the middle Saxon period onwards, alongside increased diversification including the incorporation of rye and oats (McKerracher 2016). Figures 5.24 and 5.25 depict the different percentages of crops over time (based on the charred grain assemblages) at Conington and BW3 (where sufficient archaeobotanical assemblages were retrieved). Although care should be taken with interpretation, it appears to broadly support the wider trends identified, particularly at Conington where there is a clear decrease in hulled barley and increase in free-threshing wheat, with the introduction of oats and rye, though not in significant quantities, from Period 7.2. Patterns in the BW3 data are slightly trickier to discern, although there appears to be a general increase in free-threshing wheat from the middle Saxon period onwards (54% of the assemblage), along with the introduction of oats and rye from Period 7.2. The apparent increase in spelt wheat in the middle Saxon period at BW3 should be treated with caution, as is largely based on grains from Structure 7BC.612, which were difficult to identify and may have been free-threshing wheat grains morphologically altered during the charring process to resemble spelt wheat.

The wild seed assemblage, largely derived from weeds and grasses that grew alongside crops, also bears testament to the expansion of arable practices in the middle Saxon period. This is most clearly reflected at BW3-BW5, where the wild seed assemblage increased from the middle to late Saxon periods with an increase in the variety of species, alongside an increase in seeds from species that favour heavy clay soils (González Carretero 2024). Similarly, at Conington, nitophilous species such as fat hen, knotgrass, black nightshade, stinging nettle and henbane were identified in the middle Saxon samples (Fosberry 2024), all of which are an indicator of soil enrichment and fit the patterns seen on other Anglo-Saxon sites (McKerracher 2019, 125-27).

Low quantities of chaff were identified across the Anglo-Saxon settlements, suggesting that the chaff was removed elsewhere (in the fields or barns) and brought in semi-clean into the houses. The presence of large-sized weed seeds, however, suggests that the assemblages derive from the latter stages of crop-processing (i.e. fine sieving during crop-processing, after raking and winnowing has removed most of the chaff) rather than just from cooking or storage. Lava quern fragments, related to the final phase of crop-processing, were found at Conington and Brampton West - 181 fragments at BW203; 6 fragments at BW3; 16 fragments at BW4; and 93 fragments at Conington (Fig. 5.26; Shaffrey 2024f). The presence of these quern stones indicates that subsistence-scale processing of cereals occurred and it is therefore interesting to note that the largest assemblage, by quite a margin, was from BW203, where a comparatively small number of cereal grains were identified, perhaps indicating a degree of specialisation of crop-processing within the settlements.

There was no clear evidence for archaeological features associated with arable farming, with limited evidence for field systems, with the exceptions of FS2 and FS3 in BW4. The majority of the fields would have been located beyond the settlements and it is possible, although difficult to prove, that some of the Roman field boundaries may have continued in use (e.g. linear boundaries 105 and 205 at Brampton West), or that some of the later (i.e. medieval) field boundaries may have had earlier origins (e.g. Ditches 7A.55 and 10.560). Similarly, there was no evidence for structures associated with crop-processing or grain storage, likely because these activities took place beyond the settlement cores and because such structures are often harder to recognise in the archaeological record.

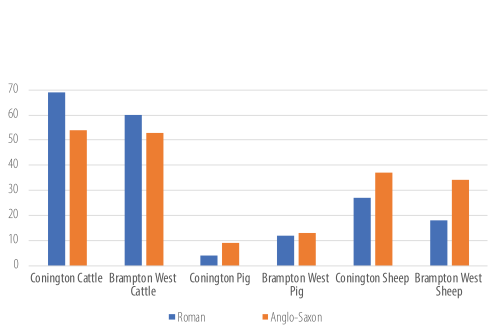

Cattle was the mainstay of the pastoral economy at all the settlements, with significant cattle bone assemblages retrieved from BW203 (NISP 1559) and Conington (NISP 1729), in contrast to smaller assemblages at BW3 (NISP 469) and BW4 (NISP 49) (see Fig. 5.27, which shows the relative proportions of main domesticates by NISP; see also Wallace and Ewens 2024 for overview). At BW203, analysis of the cattle assemblage has shown that cattle were generally slaughtered between 18 months and 3 years of age suggesting they were primarily kept for meat production, with only four foetal bones indicating that stock breeding likely took place elsewhere (Faine 2024b). At Conington, a similar age profile at death was identified (between 18 months and 30 months), although foetal bones were also recovered indicating that there was a breeding population on or near the settlement (Ewens 2024c).

Although cattle was the mainstay of the pastoral economy, the Anglo-Saxon period in central England is characterised by the increased importance of pig (and, in the A14 examples, sheep), alongside a corresponding decrease in cattle (Albarella 2019, 153). The A14 settlements fit this broad trend (Fig. 5.27). Analysis of the pig assemblage indicates that the majority of animals were culled once they reached optimum meat weight, with some examples of older breeding sows. Analysis of the sheep assemblage indicates that the focus was on meat production, with dairying, breeding, and utilisation of wool secondary. An interesting difference is noted in the middle Saxon assemblage at Conington, where a relative lack of sheep at their prime age for meat production (between 2-4 years) may suggest that such animals were exported to a consumer site, to market, or as part of a tribute, perhaps fitting with the trend of specialisation in flock usage from the middle Saxon period onwards (Albarella 2019).

There was also evidence for the exploitation of wild resources such as game mammal and fowl, wild bird species, and amphibians, which is relatively unusual for middle Saxon settlements. Evidence for the hunting of red and roe deer for venison was identified at all settlements (NISP 7 at Conington, NISP 12 at BW203, and NISP 3 at BW3). Wild fare (hare, woodpigeon and pheasant) was also occasionally exploited, though in small numbers. A very small assemblage of fish bones was also recovered (pike and whiting from Conington, and eel, bream, dace, roach, cyprinid and salmonid from Brampton West), along with two finds related to fishing at Conington - what has since been identified as a fishhook (F32093) and net sinker (F32079 ).

As is typical for most early and middle Saxon settlements, the most heavily represented craft activity was textile manufacture. In total, 100 objects relating to this were identified at Conington, 40 at BW203, and 26 at BW3 (Blackmore 2024e). In general, weaving activities were best represented (loom weights, thread pickers and other weaving tools), with fewer objects related to spinning and the production of thread (woolcombs and spindle whorls). There is also evidence at Conington for on-site loom weight production, with examples of unfired weights and unfired lumps of clay partially worked into the desired size for loom weights, as have been identified at Mucking (Hamerow 1993). The most interesting distinction in relation to textile working is the absence of loom weights from BW3, despite the presence of other implements associated with weaving (i.e. two thread pickers).

Less evidence for 'other' activities was identified, with few finds associated with crafts such as bone or metalworking, although it is likely that such activities were carried out at a small-scale household level. For example, a dump of horse distal metapodia and first phalanges was recovered from Structure 10.411 (BW203), likely deriving from bone working to produce sledge runners and 'neatsfoot' oil to protect leather (Faine 2024b). The collection of antler-working waste from Ditch 7BC.122 (BW4), offcuts or preparatory pieces for making composite combs, points to antler working within this settlement (Sillwood 2024c; Fig. 5.28). One Saxon pottery kiln, 7BC.235 (BW3) was identified, comprising the typical elongated figure-of-eight shape with firing chamber, rake-out pit, and fragments of daub (including an irregular large daub block that may represent kiln flooring), with 17 sherds of early-middle Saxon pottery, primarily granitic fabric, retrieved from the backfill (Fig. 5.29). Limited quantities of industrial waste were recovered from all of the settlements, mainly from BW3 where three smithing hearth bottoms, three pieces of hearth lining, and dispersed undiagnostic ironworking slag and cinder was identified - none of this was, however, in situ, with much recovered from waterholes e.g. 7BC.253 and 7BC.275 (Dungworth and Cubitt 2024c).

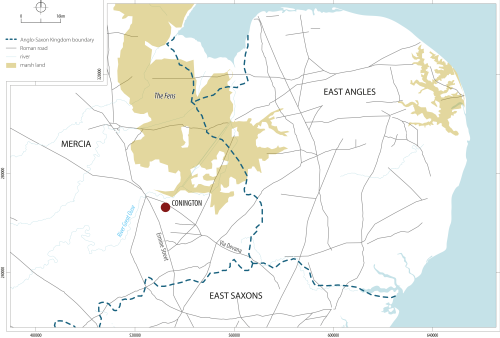

Recent work shows that the 'functional-tūn' group of Old English place-names (for instance Eaton, Stratton, Charlton, Kingston, Drayton) throw crucial light on undocumented aspects of English royal administration during c. AD 750-850. They occur in recurrent and statistically significant clusters, and a strong case can be made that they reveal structures of organisation, defence and communication in the era of Mercian supremacy (Zanella 2015; Blair 2018, 179-80, 193-228). Among them is cyninges-tūn, 'king's tūn', of which the modern form is normally Kingston but in this case Conington. The late Jill Bourne transformed our understanding of this compound (Bourne 2017). She showed that a 'kingston' was not (as one might naturally suppose) a royal residence, but instead a subsidiary administrative installation that might be better translated as something like 'customs-office' or even 'police-station'. It was to a cyninges-tūn near Dorchester (Dorset) that a luckless royal reeve tried misguidedly to direct the first shiploads of Vikings in the 790s (Blair 2018, 224-6). Bourne also showed that (especially in Wessex, where they concentrate) 'kingstons' tend to be spaced out along the lines of Roman roads: clearly they had a close connection with the overland transport system.

The outstanding importance of Conington is that it shows us - for the first time ever - a 'kingston' as a solid archaeological reality. Given the context and date that has been inferred for these names, there can be virtually no doubt that the multiple 8th-century ditched enclosures, containing regional and foreign pottery imports, belong to the settlement that originally bore that name. They come closest in form to the smaller complex at Higham Ferrers (Northamptonshire), which serviced a known residence of King Offa (Hardy et al. 2007; Blair 2018, 209-11, 250-2), and it is intriguing that a female corpse (in that case dismembered) was also found in the boundary ditch there.

In conformity to the 'kingston' model, Conington is on a Roman road, the Via Devana between Godmanchester/Huntingdon and Chester/Cambridge (Fig. 5.30). It is nearer to the former, and purely on topographical grounds it seems most likely to have been attached to a royal power-centre in the Huntingdon area. One of the great Mercian-period arteries of travel and transport was the River Great Ouse, which flows past Bedford, St Neots, Huntingdon and Ely, entering the Wash at the point where Ipswich ware was landed from coastal ships for freighting up-river (Blair 2018, 180). Domesday Book (fos. 203-203v) shows a concentration of royal land at Huntingdon, Hartford, Brampton and Godmanchester. Most royal centres in Mercia are undocumented, and this is the strongest combination of evidence that one could reasonably hope to find.

One other place-name completes this remarkable picture: Fen Drayton, on the other side of the Via Devana some 2km north-east of the Conington site. The compound Drayton (dræg-tūn) refers to the action of dragging or hauling; topographical analysis shows that it occurs at nodal points on the Anglo-Saxon communications system, such as boggy river-crossings or trans-freighting points between road and river transport (Blair and Cole in prep; Blair 2018, 127, 261-2 for comparable cases). It clearly is not coincidental that Fen Drayton, as well as facing Conington across the Roman road, is only 2km from the Great Ouse in the opposite direction. This dræg would have traversed the waterlogged alluvial meadows between the Ouse and the Roman road, perhaps with the help of some physical structure such as a timber causeway or slipway.

It was surely by this route that Ipswich ware and north French wares reached the Conington site, having come up the Ouse from the Wash. The Maxey ware could have come more circuitously by water to the Ouse, or by road along Ermine Street and the Via Devana. A good deal can be learnt from place-names and topography, but the Conington site makes a spectacular archaeological contribution that takes understanding to a new level.

This final section discusses the evidence for the Anglo-Saxon people and their daily lives. This is a difficult area to understand; however, glimpses into these individuals can be gained through burial evidence and the finds assemblages.

Despite the proliferation of Anglo-Saxon settlement, the remains of only ten Anglo-Saxon individuals were identified across the A14 - two cremation burials and eight inhumations (Table 5.8; see Henderson and Walker 2024g for overview). This is in contrast to other Anglo-Saxon sites in the area with large cemeteries - 150 inhumations at Oakington (Mortimer et al. 2017), 125 inhumations at Hatherdene Close in Cherry Hinton (Ladd and Mortimer 2017), and 148 inhumations at Edix Hill Barrington (Malim and Hines 1998). This suggests that the cemeteries that accompanied the A14 settlements were located separately, beyond the excavation areas and away from the settlement cores.

One burial was dated to the early Anglo-Saxon period - the 6th to 7th century Burial 31.83 positioned adjacent to a late Roman trackway and away from all other known Anglo-Saxon activity (identified during trial trenching). Early Anglo-Saxon cemeteries are often found close to, but separate from, settlements and were often relatively large and long-lived - the A14 example is clearly part of a completely different tradition from this. Increasingly close spatial relationships between cemeteries and their associated settlements are identified from the middle 7th century onwards, with it being common for middle and late Saxon settlements to include a small number of burials, such as the two groups of burials at Yarnton, Oxfordshire, and the 26 graves at Bloodmoor Hill, Suffolk (Hamerow 2010). This is the case with the A14 examples, with a small cemetery comprising four inhumations at Conington (Fig. 5.31). Radiocarbon dates and their spatial relationship suggest that the individuals were likely buried within a generation. Individual disturbed burials were also identified at BW3 (7BC.437) and BW203 (10.415), which may be the remnants of similar small burial groups within or close to the settlements, although the remarkably small number of these in contrast to the scale of settlement is noteworthy. This move towards including burial within the settlement space reflects a change in attitude towards the dead and may represent attempts to strengthen and legitimise claims to land and resources, at a time when other changes were taking place in settlement structure and agricultural practices (Hamerow 2010).

Many of the burials were poorly preserved, such that little can be said about the individuals. The burials included five adults and two subadults, with two females and one probable male (Henderson et al. 2024; Henderson and Walker 2024e). Isotope analysis suggests that all three inhumation burials tested (10.415, 32.210, 7BC.437) were raised locally, with the isotope values for 10.415 and 7BC.437 indicating a possible delayed end to the weaning curve at between 3.5 and 4.5 years of age. Dental pathology was identified on 10.415 and 7BC.437, with caries and calculus deposits identified on 7BC.437 likely caused by severe dental wear and a diet rich in sucrose or other carbohydrates. Evidence for the early stages of joint disease was observed in the right hip of Burial 32.199, reflecting the maturity of the individual (≥46 years).

| Landscape block | Group | Settlement | Land use | Period | Type | Sex | Age | Radiocarbon date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fenstanton Gravels | 31.83 (TT) | - | - | 7.1 (Early Saxon) | I | cal AD 540 to 640 | ||

| Brampton West | 10.415 | BW203 | - | 7.2 (Early-Middle Saxon) | I | adult | ||

| Conington | 32.199 | C5 | C1 | 7.2 (Early-Middle Saxon) | I | Female (biological) | ≥46 years | cal AD 640-780 (SUERC-92298) |

| Conington | 32.200 | C5 | C1 | 7.2 (Early-Middle Saxon) | I | adult | ||

| Conington | 32.201 | C5 | C1 | 7.2 (Early-Middle Saxon) | I | adult | cal AD 647-766 (95.4%) (SUERC 92298) | |

| Conington | 32.204 | C5 | C1 | 7.2 (Early-Middle Saxon) | I | subadult | ||

| Brampton West | 7BC.437 | BW3 | - | 7.3 (Middle Saxon) | I | ?male (biological) | 36-45 years | cal AD 773-888 (95.4%) (SUERC-91513) |

| Conington | 32.210 | C5 | E6 | 7.3 (Middle Saxon) | I | Female (genetic) | 12-17 years | cal AD 680-879 (95.4%) (SUERC 75287) |

| Alconbury | 2.7 | A5 | - | 7.3 (Middle Saxon) | C | 760 to 410 cal. BC (SUERC-91044) | ||

| Alconbury | 2.8 | A5 | - | 7.3 (Middle Saxon) | C | cal AD 770-938 (95.4% probability, SUERC-91506) |

Burial 32.210, the female aged approximately 15 years buried on top of the backfilled gateway at Conington, is of particular interest in terms of the skeleton and its positioning (Fig. 5.32). The body had been placed in an incredibly unusual position, extended and prone (face-down) in the uppermost fill of the eastern post-pit of the gateway. The left elbow was flexed at c. 90 degrees with the left hand beneath the pelvis, the right hand under the right femur, and the feet together. A bone sample returned a date of cal AD 680-879 (SUERC-75287). Prone burials are rare, with Reynolds identifying this as one of the four 'deviant' types of burial in Anglo-Saxon England (Reynolds 2009). It has been interpreted as reflecting 'otherness' or for people who have broken a taboo in society, being used for those who suffered violent or unexpected deaths, or as a way of removing the power from a 'dangerous' body (Harman et al. 1981, 167-8; Reynolds 2009, 54, 8). The apparent restriction of the lower limbs of Burial 32.210, with the possibility that the ankles were bound, may indicate that there was a desire to make the corpse 'safe' to the living. It might also be interpreted as a form of symbolic closure of the enclosure, with the added insurance of prone burial to prevent the return of the soul and the location in the entranceway emphasising a degree of communal control over the body and spirit. Other examples of middle Saxon prone burials associated with enclosure entrances included two at Catholme in Staffordshire (Reynolds 2009, 218-19), and an adult female, a possible execution victim, in the 9th-century backfill of a boundary ditch at Higham Ferrers (Hardy et al. 2007). Certainly, the Conington individual was treated differently in death from the rest of the community, with her death potentially performing some sort of important role in relation to the 'end' of the settlement.

In terms of the skeleton itself, isotope analysis indicates that she was raised locally, with aDNA analysis indicating that she was a first-generation migrant or recent descendant of migrants from somewhere further east, possibly Scandinavia, North-Eastern or North-Central Europe (Silva et al. 2024). This, although only one individual, is consistent with studies suggesting there was a persistent influx of people into eastern England from central-northern Europe and southern Scandinavia (Gretzinger et al. 2022). Studies of cemeteries in the region have identified variations in ancestry, with that at Oakington containing a mix of native and migrant ancestry (Schiffels et al. 2016). Pathological bone changes indicate that Burial 32.210 suffered episodes of ill health or under-nutrition in early life (seen in the poor dental health and porotic hyperostosis) and carried out activities that placed a strain on the back (three lumbar vertebrae had Schmorl's nodes). Spina bifida occulta, a hereditary or birth-related defect, was also identified.

The majority of the Anglo-Saxon finds were utilitarian and typical of rural domestic sites, reflecting the relatively low status of the A14 Anglo-Saxon communities (Blackmore 2024e). There were few finds of any status, with the exceptions of the crumpled mount with repousse Style II decoration (F10003) from Well 10.537 (BW203), and the fragment of a high-status colour Roman bowl/dish glass (F32246 ) from Burial 32.200 (C5), which may have been collected as an amulet. The dress accessories (47 from Brampton West, 24 from Conington) mainly comprised pins and brooches, with the narrow range of forms suggesting a degree of conservatism and/or limited choice. Items associated with personal care were rare but included combs (18 from Conington and eight from Brampton West), including a highly unusual 6th to 7th century comb (F12661) from SFB 12.82 (BW203) and a large and ostentatious antler comb of double connecting plate type (F32141) from SFB 32.42 (C5). In terms of objects associated with household activities, knives were the most common artefact type (six from Conington and 18 from Brampton West), alongside other household items such as an iron pan, a flesh fork, pot hooks, and other utensils. A lock and key from Well 7BC.363 (BW3) suggests a need for security. Other finds of particular interest include a possible pair of compasses (F73227) and spatulate tool (F73237) from Well 7BC.725 (BW3).