Figure 1: Reconstructed kitchen at Blakesley Hall, Birmingham

In England over a thousand historic houses are open to the public on a regular basis, and these form an important part of the historic environment (Hudson 2010). The historic environment has been identified in English Heritage's 'Power of Place' report as being significant in helping root people in the place they live, in education, and for the economy (English Heritage 2000). Further research has identified ways in which the historic environment can be an element of local identity and can help to foster local pride (Bee 2010, 2). The ways in which the past is presented and marketed have been identified as central to the ways in which it can be understood and used in the present (Hann 2008, 16; Jenkins 2010, 3). Physical alterations are commonly made to houses for many reasons including maintenance, changing layout, extension or transformation of function. Archaeologists record such changes to buildings in order to gain an understanding of the evolving social meanings incorporated in buildings (Giles 2000; Barrett 1987).

Research and legislative developments over the last ten years have seen a comprehensive approach to the protection of the historic environment within the context of change and development, especially in the recently published PPS5. Part of this process involves the thorough recording of change to historic places as it happens, for example, 'HE12.3: local planning authorities should require the developer to record and advance understanding of the significance of the heritage asset before it is lost'. There is a presumption towards retaining the material evidence itself wherever possible, while recognising that, 'intelligently managed change may sometimes be necessary if heritage assets are to be maintained for the long term' (Communities and Local Government 2010).

Historic houses evolve over time, and continue to be altered in redevelopment for habitation, reuse or display to the public. In many cases the process of interpreting historic houses for presentation to the public has involved structural changes, and it is these which are being considered here. These changes can range in scale and impact, from internal refurnishing (as seen at Blakesley Hall, Birmingham; Fig. 1) to rebuilding sections of a structure or relocating it to a new site (as seen at the Weald and Downland Museum; Fig. 2). The history of such reconstructions now stretches over a hundred years, and in some structures layers of change and interpretation are adding significantly to the complexity of the building. This recent history of houses is seldom the focus of interpretation at homes displayed as heritage sites, but in many cases can be seen to affect their structure and appearance significantly. This article looks at changes made to houses over the last 130 years - from which time buildings commonly started to be opened to the public as heritage sites, and works were guided by conservation principles, as set out by the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) in their 1877 Manifesto. Changes made over this period have altered buildings in different ways, affecting spatial layout, structure and construction, and changing function.

This article aims to investigate two questions: how have past practices in historic building reconstruction evolved? And, how might an understanding of this history inform current and future works to historic buildings? This will be approached through a study of the houses in England constructed between c. 1400 and c. 1600 which are currently open to the public (a total of 112 examples). The buildings were found through internet searches of tourism websites and include buildings managed by large organisations like English Heritage and the National Trust, by local authorities, by building preservation trusts, and by private individuals, some of whom are affiliated to groups like the Historic Houses Association. In order to answer the over-arching research questions, it will be important to consider a series of subsidiary questions. How have approaches, including philosophies and physical practices, towards the reconstruction of historic buildings changed since the late 19th century? In what ways have the institutions, organisations or individuals undertaking the reconstruction differed in their aims and approaches to historic buildings? What impacts have the conservation movements had on historic building reconstruction?

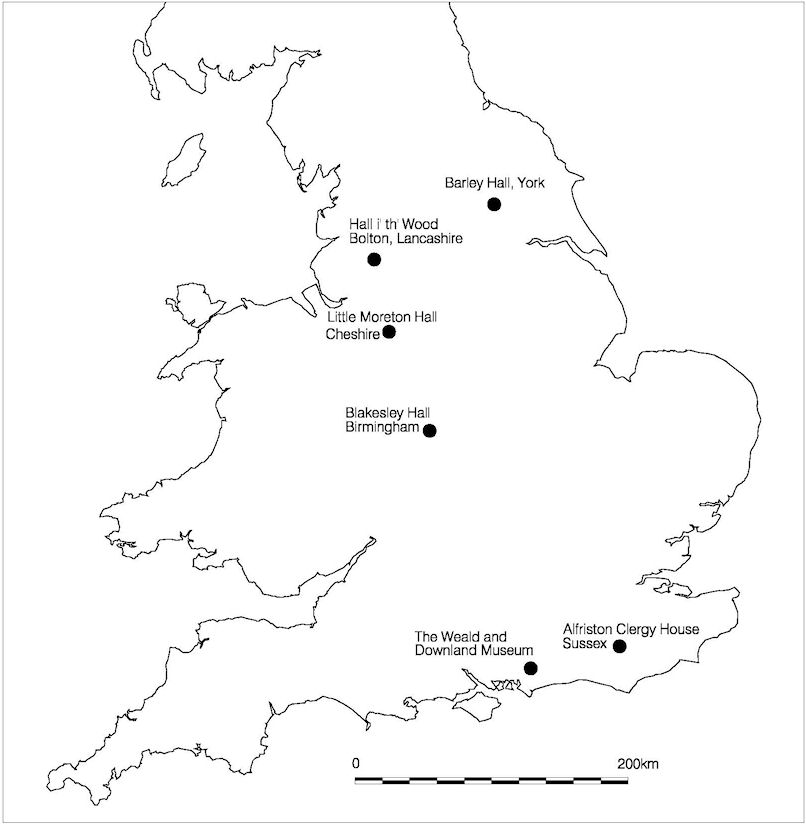

Specifically, a series of case-study buildings will be considered: Alfriston Clergy House in East Sussex; Barley Hall in York; Blakesley Hall, Birmingham; Hall i' th' Wood, Bolton; Little Moreton Hall, Cheshire ; and the Winkhurst Farm and Bayleaf Farmstead, Weald and Downland Museum, West Sussex. The locations of these houses are shown on the map (Fig. 3). These case studies exemplify some of the different approaches taken to historic buildings at different times over the last 130 years.

Figure 3: Location map of case study buildings (clickable).

For the purposes of this article, all works that alter buildings in the process of interpretation of them for the public have been termed 'reconstruction'. Contemporary terminology varies in meaning, and reconstruction is intended to be an over-arching term which takes in a range of approaches to display the building as a heritage site.

The term 'restoration' has long been used to describe work to historic houses. The dictionary definition is, 'To bring back to its original state', and English Heritage define the term, 'Restoration is intervention made with the deliberate intention of revealing or recovering a known element of heritage value that has been eroded, obscured or previously removed, rather than simply maintaining the status quo'. The term has always been a contentious one; John Ruskin abhorred the idea, 'restoration means the most total destruction which a building can suffer: a destruction out of which no remnants can be gathered: a destruction accompanied with false description of the thing destroyed' (Ruskin 1849, 179). Similarly, in the Manifesto of the SPAB, William Morris describes it as 'a strange and most fatal idea' (SPAB 1877). When working on Alfriston Clergy House, the SPAB and Octavia Hill of the National Trust agreed it should be restored, 'in so far as that odious word means preservation from decay' (Waterson 1994, 41-2).

English Heritage now use the term with far more positive connotations than early conservationists, and their advice is that:

Restoration to a significant place should normally be acceptable if:

Further advice suggests that, 'a subtle difference between new and existing, comparable to that often adopted in the presentation of damaged paintings, is more likely to retain the coherence of the whole than jarring contrast' (English Heritage 2008, 55)

John Ruskin was keen to identify the difference between 'restoration' and 'repair'. The latter was considered only to involve works necessary to maintain the structural stability of a building. A building, he believed, should remain 'honest' to its construction (Ruskin 1853, 312). One of his seven lamps of architecture is the lamp of memory, 'I believe that good men would truly feel this: that having spent their lives happily and honourably, they would be grieved...that the place of their earthly abode, which had seen and seemed almost to sympathise in, all their honour, their gladness or their suffering - that this with all the record it bear of them...was to be swept away as soon as there was room made for them in the grave' (Ruskin 1849, 187).

It was in the work of Ruskin and William Morris that the modern ideas of 'conservation' were born. Conservation work is that which prevents the deterioration of a building or object, while maintaining material authenticity - in Art History this is seen as re-establishing the unity of a work without producing a new object and without erasing every trace of the passage of time (Brandi 1996, 231). As conservation becomes part of the history of the work of art, phases of reconstruction become part of the history of the house (Brandi 1996, 235).

Customarily, conservation and restoration are presented as two alternative choices. It is essential to differentiate between conservation and restoration...Fundamentally, conservation may be defined as an operation aiming above all to prolong the life of an object by preventing, for a more or less long period of time, its natural or accidental deterioration. Restoration, on the other hand, may rather be considered a surgical operation comprising in particular the elimination of later additions and their replacement with superior materials, going on occasion as far as to reconstitute what is called–incidentally, in a somewhat incorrect manner–its original state

(Berducou 1990, 3-15).

One of the principles that has grown out of the conservation movement is 'reversibility', the desire for all modern insertions to be removable, all modern treatments reversible, so that the object can be returned to its original form if it is considered desirable to do so (English Heritage 2008, 46; Price et al. 1996, 6-7). In practice this is very difficult to achieve with an object as complex as a historic building. Likewise, materials used have often been selected to conform with a conservation principle: the SPAB has long advocated modern materials clearly visibly different from historic material; change should be 'wrought in the unmistakable fashion of the time' (SPAB 1877). In some projects traditional materials are used for structural elements, while more modern types are used for features that can be removed and altered at a later date.

Terms like 'recreation', 'renovation', 'rebuilding' and 'reconstitution' have been used historically and create a feeling of confidence in the works, and a sense that the work carried out was accurate to a period in the past, and was founded in fact. Since the 1970s the term 'conservation' has been used more commonly, the works done under this title being intended to protect a building from further decay. 'Preservation', on the other hand, implies not actively destroying the building.

The use of the term 'reconstruction' through this article implies that there is 'construction' work undertaken, which can be structural alterations to the building or construction of new images of the past through illustrations or works like refurnishing. This is done with the overarching aim of making the building as it was at some time in the past, thus 're-construction'.

In recent years guidance for reconstruction work has come from a range of fields and movements. Art history has developed some of the key guiding principles now in application (Price et al. 1996). There are many parallels between the fields of art and archaeology. Art historians may want to dismantle or sample in order to understand the processes of creation, and so may buildings archaeologists (Price et al. 1996; Grenville 1997) The emphases are different, but the aims of building and art conservation are similar: the preservation of objects from the past in order to gain an understanding of history, life and approaches at the time, and for touristic and aesthetic purposes. The issues are similar too: both groups of conservators debate whether to return an item to its original form as it was created by the builder or artist or whether to preserve the different phases of alteration through time (Price et al. 1996, 7).

Reconstruction work is debated within the fields of archaeology, architectural history, conservation, and art history (UNESCO 1972; Price et al. 1996), but is broadly philosophically accepted on the basis that it enables widespread access to and understanding and enjoyment of buildings (Borley 1997; Binney and Hanna 1978). It is advisable that works are thoroughly recorded, and presented as part of the history of the building (Sharpe 1999, 3-34). This research has found, however, that, historically, works to buildings have been recorded in varied and piecemeal ways - material often being held at the building, sometimes incorporated into conservation management plans, and sometimes incorporated into local archives or Historic Environment Records. Many of the archives consulted during this research were informal in nature. When works undertaken on historic houses are recorded in the archive, the overall aims and thought-processes behind the desired alterations to the structures of the buildings are seldom explicit. The detailed nature of alterations and the underlying philosophies behind these are interpreted from the building and the written record of its recent history. Such records and an analysis of change to a building would aid management of all historic houses, help visitor understanding of the building, and inform any future works that may be undertaken.

All reconstruction works on historic buildings are different and their impacts on the buildings vary considerably. Some buildings have undergone several phases of alteration, creating layers of accumulated changes which have a significant impact on the structure; in others a single phase of reconstruction has made drastic changes and some buildings have undergone minor alterations that do not significantly affect visitor access or understanding. Figure 4 shows the number of phases of reconstruction identified in each building considered as part of this study. The number and type of phases of reconstruction will be discussed for each of the case study buildings, but an overall pattern can be seen of repeated reconstruction at some buildings and minimal intervention at others. The case studies included here illustrate these different approaches and histories of buildings.

The ways in which successive generations have viewed historic buildings, altered them and passed them on to the next has had a long-lasting impact on the buildings themselves and the ways in which they are viewed by the visitor. Archaeologists are now more aware of the modern cultural perceptions they bring to their analysis of sites, buildings and objects (Hodder 2003, 111-12). This study, in charting the changes in approach, aims to help develop an understanding of the context that may have shaped the ways in which buildings have been reconstructed, and affected their present structure, appearance and interpretation.

© Internet Archaeology/Author(s)

University of York legal statements | Terms and Conditions

| File last updated: Mon Jan 24 2011